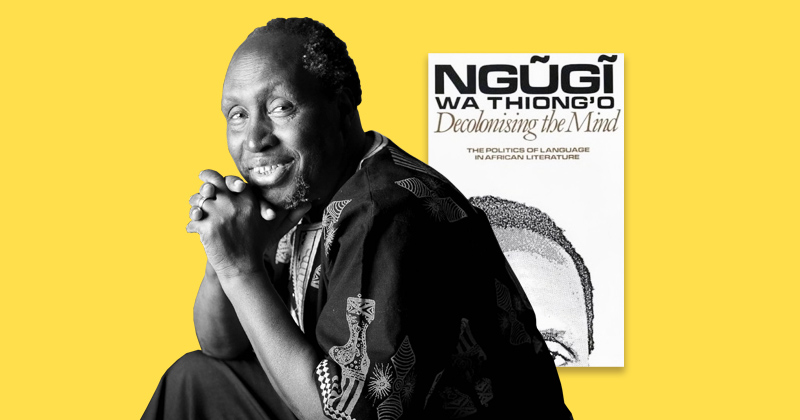

Some writers craft their words purely for the sake of storytelling, their work driven by the potential for commercial success. This is the first level—write a compelling piece of fiction, and it sells. But then there is a second level, where the writer transcends mere entertainment and commercial gain, writing with a higher purpose—a mission. Such a writer is Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o.

Ngũgĩ’s journey through literature unveiled to him the profound cultural loss Africa was experiencing. He posed a critical question: Can an African writer who writes in English truly call their work African?

Language as the Vessel of Culture

Ngũgĩ challenges the very essence of identity through language, arguing that language is not just a tool for communication but a vessel for culture, history, and worldview. When African writers express themselves in English, they risk losing the richness, depth, and perspectives embedded in their native tongues. Language carries the nuances of a people’s collective experiences, their humor, their idioms, and their philosophies.

The Impact of Colonialism on African Languages

In his seminal work, “Decolonising the Mind”, Ngũgĩ calls upon Africans to reclaim their languages. He argues that language is intimately tied to cultural identity, and by continuing to write in the colonizer’s language, Africans remain mentally and culturally subordinate. As Ngũgĩ states:

“If you know all the world languages but not your mother tongue, that is enslavement. But if you know your mother tongue and add all the other languages, that is empowerment.”

This powerful statement encapsulates his belief that indigenous languages must be preserved, revitalized, and enriched with contemporary knowledge.

Parallels with Europe’s Linguistic History

Ngũgĩ draws an illuminating parallel between Africa’s current linguistic situation and Europe’s past. There was a time when Latin had “colonized” Europe, dominating intellectual and cultural discourse. It was only after Europe abandoned Latin and embraced its mother tongues—English, German, Italian, and others—that the Renaissance occurred. This cultural and intellectual flourishing paved the way for the Industrial Revolution, fundamentally transforming Europe.

He argues that Africa, too, can have its own cultural renaissance if it returns to its indigenous languages. Just as Europe unlocked its potential by embracing its own languages, Africa can chart its course by empowering African languages.

Language, Identity, and Empowerment

For Ngũgĩ, language is more than a preference; it is deeply tied to identity and empowerment. Continuing to write in the colonizer’s language perpetuates the intellectual and cultural domination that colonialism left behind. It robs Africa of its voice and cultural soul. Reclaiming African languages would allow the continent to write its own stories, reflect its own experiences, and shape its future without the filter of foreign tongues.

A Political Act of Resistance

Ngũgĩ’s decision to write in Gikuyu was not just an artistic choice—it was a political act of resistance. He notes:

“The languages of power in most post-colonial African countries are still European languages.”

By reclaiming African languages, Ngũgĩ believes African writers and thinkers can break free from the colonial mindset that prioritizes foreign validation. Writing in native languages reconnects Africans with their history, oral traditions, and cultural identity, creating literature that truly reflects African realities.

Decolonising the Mind

In “Decolonising the Mind,” Ngũgĩ articulates the concept that colonialism does not only reside in political and economic spheres but also in the minds of the colonized. Language becomes a tool of control, shaping thoughts and perceptions. By continuing to prioritize European languages, Africans may unknowingly perpetuate colonial structures in education, literature, and daily life.

Implications for Contemporary African Writers

Ngũgĩ’s stance presents a challenging dilemma for African writers:

- Authenticity vs. Accessibility: Writing in indigenous languages may limit the immediate global reach of African literature but enhances its authenticity.

- Preservation of Culture: Emphasizing native languages aids in preserving cultural heritage and promotes linguistic diversity.

- Educational Systems: There is a need to reform educational curricula to include and prioritize African languages.

A Call to Cultural Awakening

Ngũgĩ’s work powerfully reminds us that language shapes how we see the world. By reclaiming our languages, we can reclaim our stories, identities, and futures. For Ngũgĩ, this isn’t just a literary argument; it’s a call to cultural awakening and empowerment.

When he asks if an African writer can truly call their work African when written in English, he challenges whether that writer can fully capture the African experience without the cultural and linguistic framework that only native languages provide.

Towards a Culturally Liberated Africa

In essence, Ngũgĩ’s vision is of a culturally liberated Africa that learns from history, embraces its languages, and steps into the future with its own voice. He reminds us that, just like Europe’s Renaissance, Africa’s cultural rebirth may very well begin when it reclaims the languages that reflect its true self.

Conclusion

Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o stands as a beacon for the importance of language in cultural identity. His advocacy encourages not just African writers but all individuals to consider the profound impact of language on our perceptions, relationships, and societies. Embracing one’s mother tongue is not a step backward but a stride towards genuine empowerment and self-realization.

References:

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. (1986). Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. Heinemann Educational.

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o. (2009). Something Torn and New: An African Renaissance. Basic Civitas Books.

- wa Thiong’o, N. (1992). Moving the Centre: The Struggle for Cultural Freedoms. James Currey Publishers.