Every generation has its soundtrack, and every era finds its rhythm in the hands of the youth. From traditional ceremonies to viral anthems, Kenya’s musical story has always been shaped by its younger generation. Why? Because youth breathe life into culture—they take inherited sounds, add their twist, and turn them into movements. The result? A constantly evolving soundscape that defines Kenya’s identity and reflects its dynamic spirit.

Pre-Colonial Period: Traditional Music

Indigenous Roots

Music in pre-colonial Kenya was integral to community life, often tied to ceremonies, rituals, and daily activities. Each of Kenya’s over 40 ethnic groups developed unique musical traditions:

- Instruments: Indigenous instruments included drums (ngoma), lyres (nyatiti among the Luo), flutes, horns, and stringed instruments like the obokano of the Gusii people.

- Styles and Themes: Music served various purposes, such as storytelling, social commentary, and spiritual practices. For example:

- The Kikuyu used songs during planting and harvesting seasons.

- The Maasai incorporated chants and rhythmic dances into rites of passage and warrior ceremonies.

Colonial Era (1895–1963): Influence of External Cultures

Missionary Influence

During the colonial occupation of Kenya (1885–1963), references to music practices were not only scarce but often racially biased. Colonial administrators, missionaries, and scientific observers viewed Kenyan music and culture through a prejudiced lens. This is exemplified in a 1936 gazette report that dismissed Turkana dances as “a large number of men walking about, stamping their feet.” Similarly, missionary Cagnolo, in The Akikuyu (Kikuyu) – Their Customs Traditions and Folklore, wrote that while music among “civilized nations” represented the soul of a people, for the Kikuyu, it merely expressed “present feelings.” Such judgments reduced Kenya’s rich cultural practices to irrelevant entertainment and undermined their significance in community life.

To the colonial administration, music and dance were seen as potentially dangerous, capable of stirring political unrest. Festive gatherings, ceremonies, and initiation rituals were heavily regulated and often required permits. This suppression curtailed traditional practices and sought to impose Western cultural norms as part of a broader strategy for control.

Amid this suppression, Christian missionaries introduced Western hymns and church music as tools for evangelism. Indigenous melodies were adapted to Christian lyrics, creating early fusions of Western and local styles. Church choirs became central to this musical blend, subtly preserving traditional harmonies and rhythms while embedding them within Christian frameworks. Despite the colonial efforts to diminish traditional music, these fusions laid the foundation for Kenya’s later exploration of blending local sounds with global influences, demonstrating resilience and adaptability in the face of cultural repression.

Swahili and Coastal Influences

By the 1940s, young Kenyan artists were experimenting with taarab, Congolese guitar styles, and local folk sounds. Jean Bosco Mwenda’s intricate guitar work, for instance, inspired a generation of musicians to create Kenya’s own hybrid sound, which would eventually lead to the birth of Benga music.

- Taarab Music: This genre, blending poetic lyrics with Arabic-inspired melodies and African rhythms, gained immense popularity in coastal cities like Mombasa and Lamu. Artists such as Siti binti Saad, though based in Zanzibar, heavily influenced the taarab sound in Kenya.

- Instruments like the oud (lute), violin, and percussion added layers of complexity to taarab, creating a timeless sound that resonated across generations.

Emergence of Popular Music

The growth of urban centers like Nairobi during the colonial period created fertile ground for the development of popular music:

- Early Recording Studios: By the 1940s, international labels like His Master’s Voice (HMV) began releasing commercial recordings of Kenyan music. These recordings predominantly featured local folk melodies and traditional rhythms.

- Independent Labels: After World War II, local record labels emerged, including Jambo Records and Africa Gramophone Service. These studios played a pivotal role in capturing and promoting the diverse sounds of Kenyan music.

Influence of Regional and International Artists

Kenya’s role as a regional music hub during the colonial period attracted influential artists:

- Jean Bosco Mwenda and Edouard Masengo, pioneering Congolese guitarists, recorded and performed extensively in Nairobi. Their intricate guitar work inspired many Kenyan musicians, shaping the evolution of the Benga genre in the years leading up to and after independence.

- The influx of these regional influences catalyzed experimentation among Kenyan musicians, fostering a hybrid sound that reflected Kenya’s cultural diversity.

Equator Sound Studios and the African Twist

In 1961, Equator Sound Studios, founded by Charles Worrod, revolutionized the Kenyan music scene. Its house band, featuring stars like Fadhili William (Malaika) and Daudi Kabaka, produced hits that captured the imagination of a newly independent Kenya:

- The African Twist, a dance and musical style inspired by South Africa’s kwela rhythm, became synonymous with Kenya’s independence era. Tracks like Harambee Harambee by Daudi Kabaka celebrated national unity and progress.

- Equator Sound’s influence extended beyond Kenya, attracting Congolese musicians and producing hits that gained recognition across the continent and beyond.

Legacy of the Colonial Era

The colonial period laid the groundwork for Kenya’s post-independence music industry. The fusion of traditional Kenyan sounds with taarab, Western hymns, and Congolese guitar rhythms created a diverse and dynamic musical landscape. As the industry matured, Kenya established itself as a regional hub for innovation, paving the way for the golden era of Benga and Afro-fusion in the decades to follow.ce Era

(1963–1980s): Rise of Popular Music

Benga Music

Origins and Characteristics

Benga, one of Kenya’s most influential and enduring pop music styles, emerged in the 1960s among the Luo people of Western Kenya. The genre arose during a time of cultural renaissance inspired by Kenya’s independence and the infusion of musical influences from across Africa.

Benga is characterized by its:

- Instrumentation: The use of electric guitars, bass, and percussion instruments defines the sound. Guitar riffs mimic the rhythms of the traditional nyatiti, a Luo string instrument, creating vibrant and melodic patterns.

- Rhythms and Melodies: The genre’s measured rhythms and danceable tunes captivate listeners, making it a staple at social gatherings and celebrations.

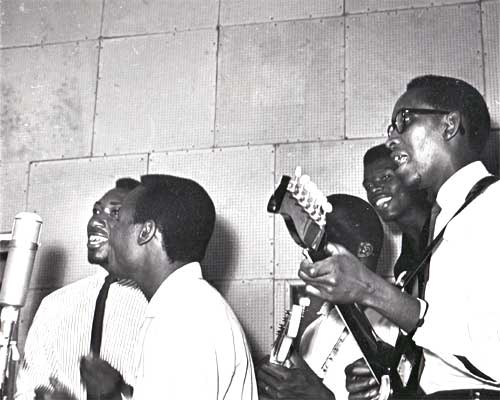

Pioneers and Key Artists

Benga’s growth was fueled by a rich pool of talented musicians whose innovation brought the genre to the forefront of Kenyan music:

- Daniel Owino Misiani and Shirati Jazz: Known as the “Father of Benga,” Misiani revolutionized the genre with his electrifying performances and recordings, making it a nationwide sensation.

- George Ramogi: A pivotal figure in the 1970s and 1980s, Ramogi helped elevate Benga to a cultural phenomenon.

- Musa Juma and Okatch Biggy: Later torchbearers of Benga, these artists introduced variations that kept the genre fresh and relevant for new audiences.

- Ayub Ogada: His 1992 album En Mana Kuoyo introduced Benga’s distinctive sounds to global audiences, expanding the genre’s reach.

Legacy and Influence

Benga’s energetic sound and cultural significance have made it a cornerstone of Kenyan music. Its influence extends beyond borders, inspiring other African genres and integrating seamlessly into Afro-fusion movements. Today, Benga continues to evolve, resonating with both traditionalists and contemporary music enthusiasts.

Political and Social Commentary

Music during this period became a vehicle for political expression and social critique:

- Artists like Joseph Kamaru used Kikuyu folk music to comment on governance and societal issues.

Kenyan Underground Hip-Hop: The Rise of Kalamashaka and the Mau Mau Movement

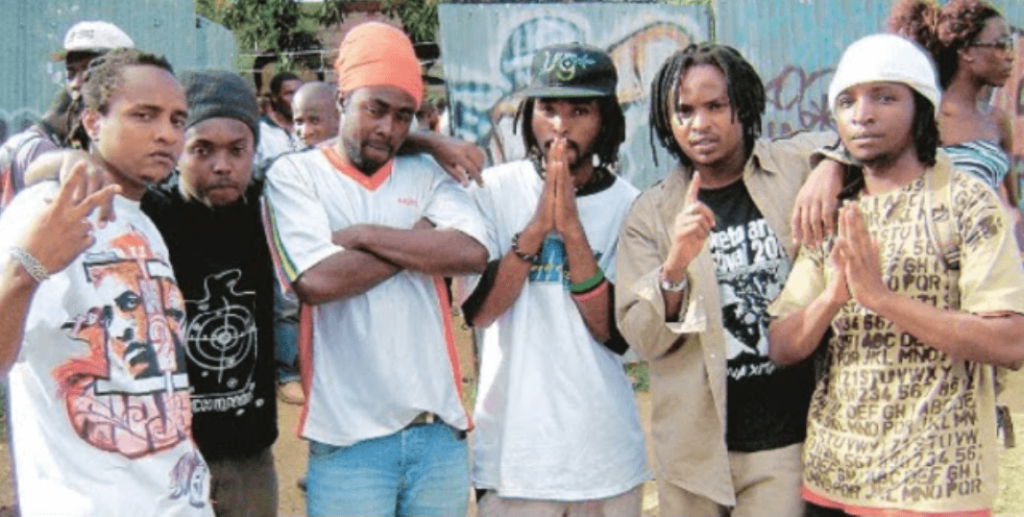

Kalamashaka: Trailblazers of Kenyan Hip-Hop

Kalamashaka, often abbreviated as K-Shaka, emerged in the late 1990s as one of the pioneering acts in Kenyan hip-hop. The name “Kalamashaka,” derived from Sheng slang, translates to “someone who has endured life’s struggles,” reflecting the group’s deep connection to the struggles of Nairobi’s urban youth. Formed by Otero, Kama, and Roba, K-Shaka quickly became a symbol of resilience and empowerment, using hip-hop as a tool to articulate the frustrations and aspirations of Kenya’s underprivileged communities.

Their breakout single, Tafsiri Hii (Translate This), became an anthem of social and political resistance, tackling issues like poverty, systemic corruption, and police brutality. The song’s raw, heartfelt lyrics, performed in Swahili and Sheng, resonated with Kenya’s youth and solidified K-Shaka’s reputation as the voice of the marginalized.

The Mau Mau Underground Movement

In the early 2000s, K-Shaka inspired a broader underground hip-hop movement known as Mau Mau, named after Kenya’s anti-colonial freedom fighters. The name symbolized rebellion, resilience, and a refusal to conform to mainstream expectations.

Structure and Philosophy

Mau Mau became more than a music collective—it was a movement rooted in the principles of activism and social justice. The movement’s artists often performed in underground venues and community spaces, prioritizing authenticity over commercial appeal. Their music highlighted urban struggles, inequality, and the fight for dignity, drawing parallels between their resistance to societal oppression and the Mau Mau’s resistance to colonial rule.

Key Acts and Affiliations

The Mau Mau movement became a breeding ground for some of Kenya’s most legendary underground hip-hop acts, many of whom would leave an indelible mark on the genre.

Mashifta

- Composed of Kitu Sewer and G-Wiji, Mashifta (a Sheng term meaning “the shifters” or “rebels” see shifta war) was one of the defining acts of the Mau Mau movement.

- Songs like Kwa Raha Zangu showcased Kitu Sewer’s sharp lyricism and ability to capture the essence of life in Nairobi’s rough neighborhoods. Mashifta’s music often blended biting social commentary with streetwise storytelling.

Wenyeji

- Another integral group in the Mau Mau camp, Wenyeji, represented the collective voice of Nairobi’s slums. Their hard-hitting lyrics and gritty beats made them fan favorites in Kenya’s underground hip-hop scene.

KSouth (K-South Empire)

- Closely affiliated with the Mau Mau movement, K-South was a duo comprising Bamboo and Abbas Kubaff. The group combined Sheng lyricism with intricate wordplay, producing hits like Tabia Mbaya and Kapuka This. Bamboo’s versatility and Abbas’ sharp, punchy delivery cemented K-South as legends in Kenyan hip-hop.

Coastal Influences: Ukoo Flani Mau Mau

- On Kenya’s coast, the hip-hop scene was flourishing with the emergence of Ukoo Flani Mau Mau. Initially operating as the Ukoo Flani clan, they featured acts like Cannibal, Fujo Makelele, and Sharama. Their music, often steeped in coastal culture, introduced a new flavor to Kenyan hip-hop.

- In the mid-2000s, Ukoo Flani Mau Mau merged with the Mau Mau movement, creating a powerful synergy that expanded the reach and influence of both groups. This merger symbolized the unity of Kenyan underground hip-hop across regional and cultural lines.

Mau Mau’s Cultural Impact

The Mau Mau movement became synonymous with authenticity in Kenyan hip-hop. It was a rallying point for artists who rejected the commercialization of music and instead chose to focus on storytelling, activism, and cultural preservation. The movement nurtured a sense of identity and pride among Nairobi’s youth, offering a platform for self-expression and community building. However, it’s crucial to note that Mau Mau and Kalamashaka were not the pioneers of hip-hop in Kenya.

Kenya’s hip-hop journey can be traced back even earlier, with trailblazers like Jimmi Gathu paving the way. In fact, Jimmi Gathu’s 1989 track Look, Think, Stay Alive is often regarded as the country’s first hip-hop music video. The video aired on Kenya Television Network (KTN) in 1990, marking a significant milestone in Kenya’s music history. The song, produced as part of a road safety campaign, showcased early attempts at integrating rap into Kenya’s music scene. Gathu’s work demonstrated that Kenyan artists were experimenting with hip-hop long before it became mainstream.

While Look, Think, Stay Alive did not spark a large-scale movement, it laid the groundwork for the genre’s development. By the time Kalamashaka and the Mau Mau movement emerged in the 1990s, the foundations of Kenyan hip-hop had already been established, albeit in isolated and experimental forms. Kalamashaka took these early influences and transformed them into a robust cultural force, infusing hip-hop with a distinctly Kenyan identity that resonated deeply with urban youth.

Thus, the Mau Mau movement can be seen as a critical chapter in Kenya’s hip-hop evolution rather than its starting point, building on the efforts of earlier pioneers like Jimmi Gathu.

Themes in Music

- Urban Struggles: Artists painted vivid portraits of life in Nairobi’s slums, addressing poverty, crime, and systemic neglect.

- Resistance: The music often critiqued the political elite, corruption, and the exploitation of Kenya’s youth.

- Cultural Pride: By rapping in Sheng and Swahili, the Mau Mau artists celebrated Kenya’s linguistic and cultural diversity, challenging Western influences in mainstream music.

Challenges and Legacy

Despite its cultural significance, the Mau Mau movement faced challenges, including limited financial resources, lack of mainstream support, and internal dynamics. However, its impact on Kenya’s music industry and youth culture remains profound.

- Influence on New Artists: Many contemporary Kenyan hip-hop artists, such as Khaligraph Jones and Octopizzo, credit Mau Mau and its affiliates as inspirations.

- Preservation of Underground Spirit: The movement’s emphasis on authenticity and activism continues to resonate in Kenya’s underground music scenes.

The Mainstream Takeover: Genge, Kapuka, and the Evolution to Gengetone

Kenyan hip-hop’s evolution in the early 2000s took two divergent paths: the underground movement, rooted in activism and social commentary, and mainstream genres like Genge and Kapuka, which dominated the airwaves with their catchy beats and explicit lyrics. These mainstream styles prioritized entertainment over controversy, but they retained a rebellious spirit that connected with Kenya’s youth.

The Rise of Genge and Kapuka

Origins and Characteristics

- Genge and Kapuka emerged in the early 2000s as distinctly Kenyan music styles that blended elements of hip-hop, dancehall, and African rhythms.

- The genres used Sheng and Swahili lyrics, creating a highly relatable language for urban youth. Their hallmark was explicit storytelling, often revolving around themes of love, relationships, and nightlife.

Key Artists and Songs

- Nonini: Widely regarded as the “Godfather of Genge,” Nonini pioneered the genre with hits like Manzi wa Nairobi, which celebrated the beauty of Nairobi women in unabashedly provocative terms.

- Jua Cali: Another Genge legend, Jua Cali, popularized hits like Nyundo, solidifying Genge’s reputation for playful and edgy lyricism.

- Viral Sensations: Songs like Manyake by Circuit and Joel made waves for their overtly explicit lyrics. The song, widely criticized for its content, nonetheless gained massive popularity among Kenyan youth, becoming a cultural touchstone for Genge’s audaciousness.

The Role of Media

Genge and Kapuka owed much of their success to radio DJs and TV presenters who acted as tastemakers and gatekeepers in Kenya’s music industry:

- Popular radio stations, such as Kiss 100 and Capital FM, frequently played Genge and Kapuka tracks, giving the genres unparalleled visibility.

- Music shows like East African Beat on TV further boosted artists, solidifying the genres’ association with mainstream success.

Group Success

Groups like P-Unit, mentored by Nonini, became breakout stars of the Genge era. Tracks such as Kare and You Guy (Dat Dendai) showcased the genre’s infectious beats and unapologetic approach to explicit topics. P-Unit’s success cemented the viability of Genge as a commercial powerhouse.

Controversies Around the Underground Movement

While Genge and Kapuka enjoyed commercial success, the underground hip-hop movement faced controversies related to its ties with gangs and violence. The underground movement, especially Mau Mau-affiliated acts, was often viewed with suspicion for its gritty portrayal of urban life, including crime and social unrest. This notoriety kept it largely outside mainstream media channels, which favored the more accessible and radio-friendly Genge and Kapuka styles.

Interestingly, both underground hip-hop and reggae culture thrived simultaneously during this era. Reggae artists and their audiences shared the underground’s rebellious ethos, making the two subcultures equally influential in shaping urban music narratives.

The Emergence of Gengetone (2015–Present)

Taking Explicit Lyrics to a New Level

Around 2015, a new genre called Gengetone emerged, pushing the boundaries of what Genge and Kapuka had established:

- Inspired by Genge’s explicit themes, Gengetone took the focus on sex, drugs, and urban youth culture to extreme levels.

- Artists like Ethic Entertainment, Sailors Gang, and Boondocks Gang produced tracks that became viral sensations, characterized by their unabashedly raunchy lyrics and energetic beats. Songs like Lamba Lolo by Ethic and Wamlambez by Sailors epitomized the genre’s raw and controversial appeal.

Teenage Adoption and Social Influence

Gengetone quickly became the soundtrack for Kenya’s teenagers, including those in primary and high schools. Its themes, while criticized by parents and educators, resonated deeply with younger audiences eager to rebel against societal norms.

Corporate Endorsement

Initially, Gengetone faced resistance from corporate sponsors due to its explicit content. However, the genre’s massive popularity and the sheer volume of traffic it generated online proved irresistible:

- Brands began sponsoring Gengetone events and featuring its artists in advertisements, recognizing the genre’s marketing potential.

- Streaming platforms like YouTube and Boomplay became key avenues for Gengetone’s growth, as artists bypassed traditional gatekeepers to connect directly with audiences.

Cultural and Economic Impact

- Traffic and Monetization: Gengetone artists amassed millions of views online, creating new revenue streams for the music industry.

- Youth Culture: The genre became a defining feature of Kenyan youth identity, reflecting their language, humor, and defiance.

The Youth as Music’s Lifeblood

From the drumbeats of ancient ceremonies to the bass drops of Gengetone, one thing remains clear: Kenya’s musical legacy is driven by its youth. They are the risk-takers, the innovators, and the dreamers who keep reinventing the soundtrack of their time.

So, whether you’re grooving to Benga, vibing to Genge, or singing along to the latest Gengetone hit, remember: it’s the energy of Kenya’s youth that keeps the beat alive. As long as there’s a new generation ready to pick up an instrument, a mic, or even just a smartphone, Kenya’s music will continue to evolve, inspire, and unite.

Signing out music haiwezi disappear listen