Labor scarcity has been a recurring theme in Kenya’s history, influencing societal structures, agricultural practices, and colonial policies. From pre-colonial systems of land use to the exploitative labor practices of the colonial era, labor scarcity profoundly shaped the lives of ordinary Kenyans. This article explores how labor shortages were addressed through innovative systems and how colonial powers exploited these shortages for their own benefit. We delve into historical examples, including polygamy as a labor strategy, feudal-like systems in Kabete, and forced labor during the Mau Mau uprising. Additionally, we will contextualize Kenya’s labor history within broader African trends as discussed in “Labour in African History.”

The Feudal-Like System in Kabete (1500s–1800s)

In Kabete, now part of Kiambu District, a system resembling feudalism emerged as a response to labor scarcity. Landowners who acquired land from the Dorobo employed serfs, known as ahoi, to cultivate the vast tracts of uncultivated land. These serfs were granted land-use rights and allowed to live rent-free, but they provided labor for clearing forests and preparing virgin land for agriculture.

For the ahoi, working the land was a means to accumulate wealth and eventually purchase their own plots, known as kīthaka. This system not only facilitated agricultural expansion but also allowed for upward mobility within the community. By the time European settlers arrived, much of the land had already been cultivated, showcasing the effectiveness of this system. Similar patterns of integrating pre-colonial production systems with new demands were observed in other parts of Africa, where colonial powers restructured labor relations to suit their needs.

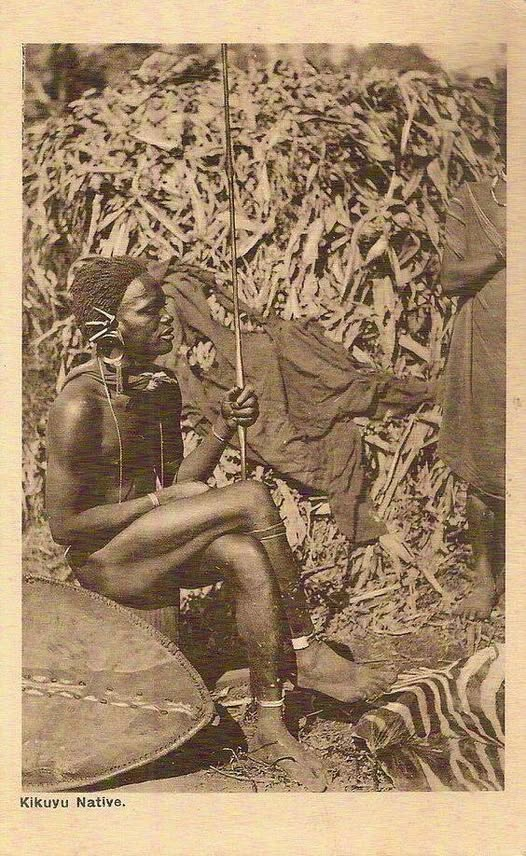

Polygamy and Labor in Pre-Colonial Kenya

Polygamy was not merely a social or cultural practice in many African societies but also an economic strategy to address labor scarcity. In a time when land was abundant but labor was not, men often relied on multiple wives and their children to form a robust workforce for farming and land management. Paramount Chief Wangombe exemplifies this practice, using his large family to secure economic stability and agricultural success.

Check Kenyan History Timeline

While polygamy wasn’t the sole solution to labor shortages, it played a significant role in creating a larger, self-sustaining labor force. This practice highlights the ingenuity of African societies in addressing the challenges of their time. As noted in broader African contexts, pre-colonial economies heavily relied on subsistence farming, pastoralism, and small-scale trade, with kinship structures often supporting these labor-intensive activities.

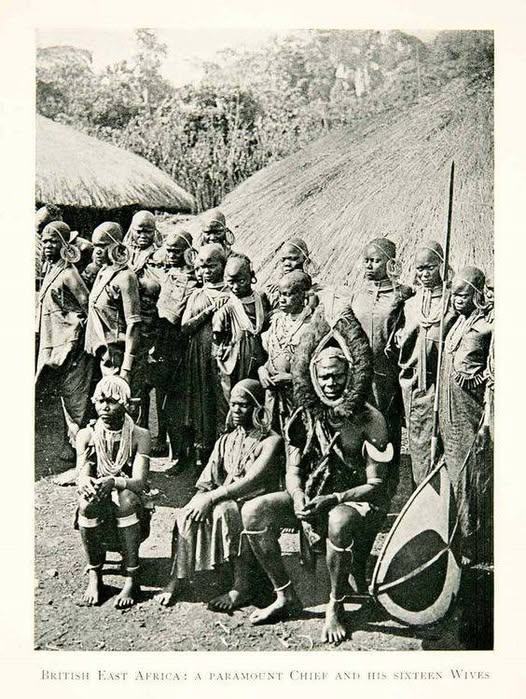

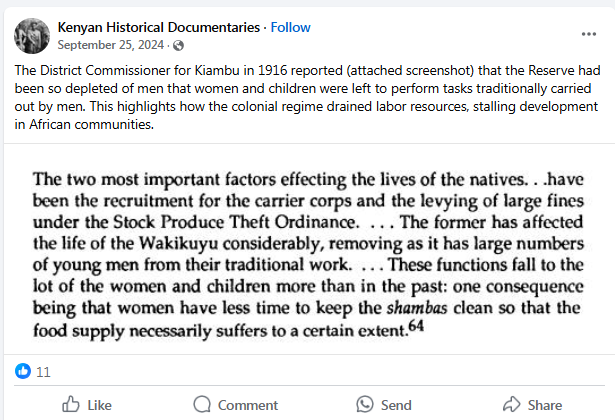

Colonial Labor Exploitation

The arrival of colonial powers in Kenya marked a turning point in labor practices. The 1916 report by the District Commissioner for Kiambu reveals how colonial labor demands drained men from reserves, leaving women and children to perform traditionally male tasks. These tasks included tilling the land and managing farms, often at the expense of food security and community well-being.

As highlighted in the “Labour in African History” report, colonial regimes across Africa employed similar tactics, introducing labor taxes and forced recruitment to compel Africans into waged labor. These strategies disrupted existing social orders and reshaped labor relations, often using coercion to maintain a steady labor supply.

Forced Labor During the Mau Mau Uprising

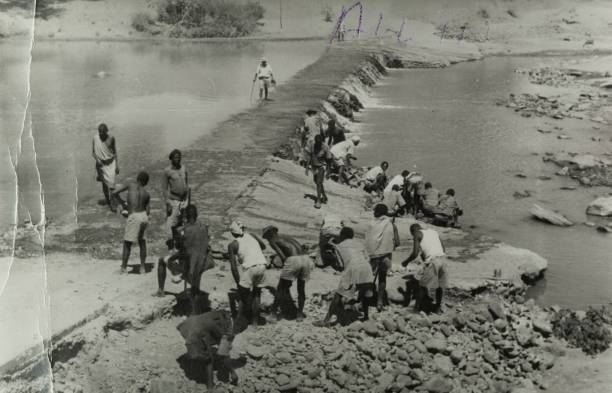

The colonial government’s exploitation of labor reached its peak during the Mau Mau uprising. Under the guise of convict labor, thousands of Kenyans were forced into grueling work conditions. These “convicts” were often Mau Mau detainees, arrested on flimsy suspicions but used as a free labor force to build infrastructure, such as the dam at Perherra plains for irrigation.

Forced labor, often likened to slavery, was widespread across colonial Africa. As noted by scholars, it was euphemistically termed “political labor” by the British and justified as necessary for economic development. Women and children were not spared, often subjected to harsh conditions that exemplified the exploitation inherent in colonial systems.

Broader African Context: Labor Regimes and Resistance

Kenya’s labor history mirrors broader trends across Africa, where labor regimes were shaped by the interplay between traditional systems and colonial capitalism. According to the “Labour in African History” report, colonial powers rearticulated pre-existing labor systems to suit capitalist demands. This often resulted in dual systems where traditional subsistence farming coexisted with waged labor.

Resistance was a recurring theme. From desertion to strikes, African workers used various strategies to contest exploitative conditions. In Kenya, the Mau Mau uprising was a direct response to these oppressive systems, as was the broader decolonization struggle across the continent.

The Legacy of Labor Scarcity

Labor scarcity in Kenya’s history reveals a recurring pattern of resilience and adaptation. From the innovative use of polygamy to the feudal-like systems of Kabete and the colonial exploitation of labor, each era demonstrates how Kenyans navigated the challenges of their time. However, the colonial period also underscores the darker side of labor scarcity, where exploitation and oppression were used to meet labor demands.

Today, these historical lessons serve as a reminder of the importance of fair labor practices and the resilience of communities in the face of adversity. As Africa continues to grapple with the legacies of colonial labor systems, understanding this history is crucial for crafting inclusive and equitable policies that prioritize the well-being of workers.

Conclusion

Kenya’s labor history, woven into the larger fabric of African experiences, offers profound insights into the interplay between economic necessity and societal resilience. From pre-colonial strategies like polygamy to colonial-era exploitation, labor has always been a critical factor in shaping the nation’s trajectory. By examining these historical contexts, we not only honor the struggles of the past but also glean lessons for building a fairer future.