As of 2019, the population of the Kikuyu people was 8,148,668, making them the largest ethnic group in Kenya. This represented 17.13% of Kenya’s total population.[1] This makes the Kikuyu the second-biggest ethnic group in East Africa after the Baganda of Uganda, whose population is estimated at 8.8 million.[2]

Today, the Kikuyu people are known as serious entrepreneurs. Their entrepreneurial skills, along with an expansion to the south that was already in place long before the Europeans ventured into the hinterlands of East Africa, have positioned them to claim a lion’s share in business and real estate in the biggest business center in East Africa: Nairobi.

But before the Kikuyu were known for business, they made their mark early in East Africa as agriculturalists. In this article, I will take you through the history of the Kikuyu people: how they found themselves in East Africa, what they did to overcome the hard country life in the remote frontiers of the 15th century, and the transitions that have made them influential figures in Kenyan politics today.

Origins and Migration of the Kikuyu

The mind’s memory, like all things, is interrupted by death. In fact, most human endeavors, especially individual-based ones, are interrupted by death. To overcome this, man (used here as short for humankind) has found an ingenious way to cooperate with others to conquer death in certain contexts. Some projects that cannot be accomplished within a single lifetime are completed through the cooperation and mutual commitment of those left to carry them forward.

In this way, man found a way to record his past before the advent of writing—by passing it orally to the young, who in turn relayed it to the next generation. While this method was not perfect, there were ways and tools to ensure that the most important details were preserved and made memorable.

For the Kikuyu, like most other tribes in Kenya, writing was introduced by Europeans in the hinterlands and by Arab influence along the coast. As Kenyans, with the exception of a small part of coastal Kenya that adopted writing as early as the 14th century through Arab influence, most tribes had to wait for missionaries in the 19th century to enter the realm of written history. Thus, before the 19th century, the richest source of history for most tribes in Kenya was oral tradition.

Now that we have that context, let’s explore the Kikuyu’s oral traditions.

The Mythological Origins: Gikuyu and Mumbi

Central to the Kikuyu identity is their origin story, passed down through generations as oral tradition. According to Kikuyu mythology, the creator god, Ngai, called their first ancestors, Gikuyu and Mumbi, to the sacred peak of Mount Kirinyaga (Mount Kenya). Ngai instructed Gikuyu to look over the fertile lands stretching below the mountain and promised him this land as a home for his descendants. He also gave Gikuyu a staff and blessings for his future prosperity.

Gikuyu and Mumbi settled at Mukurwe wa Nyagathanga, a place considered the cradle of the Kikuyu people. Together, they bore nine plus one daughters—Wanjiku, Wambui, Wangari, Waithira, Wanjiru, Nyambura, Njeri, Wangui, Nyakairu and Wamuyu[3]—who are said to have established the nine plus one clans of the Kikuyu. In time, these clans expanded and formed the foundation of Kikuyu society, with their unity and cultural traditions deeply rooted in this mythological heritage.

According to Kikuyu traditions, it is considered a bad omen to count the exact number of any living beings. To circumvent this, the practice involves declaring the number as one less than the actual count.

Kenda Mũiyũru[4]

Mount Kirinyaga remains a spiritual symbol for the Kikuyu, serving as a reminder of their divine connection to the land and their ancestors. Rituals and prayers were historically directed towards the mountain, and it continues to hold cultural significance even today.

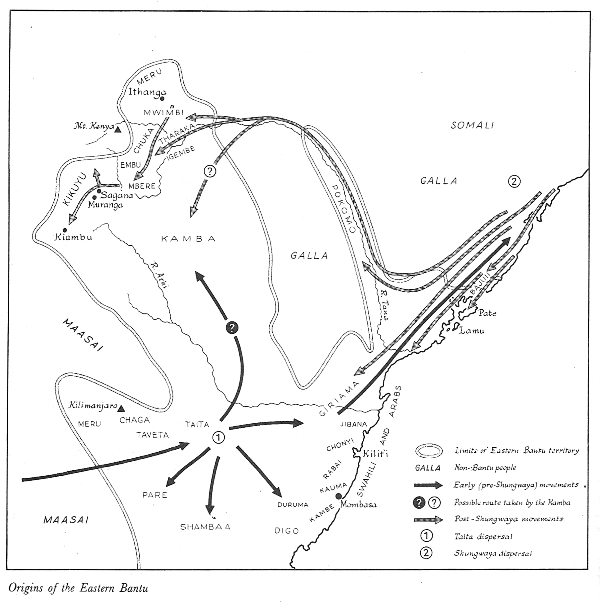

Anthropological and Linguistic Evidence: The Bantu Migration

While mythology provides the spiritual and cultural grounding for Kikuyu origins, anthropological and linguistic evidence offers insights into their broader historical migration. The Kikuyu are part of the Bantu-speaking peoples, who migrated from Central Africa thousands of years ago. This vast migration, driven by the search for fertile lands (How crazy to leave the congo rain forest and go to its edges where rainfall is likely unreliable for the most parts of the country? population increase could be a better reason but lets explore that route ext time) and better living conditions, brought the Bantu people into East Africa between 2000 BCE and 1000 CE [5].

The Kikuyu, along with other Bantu groups, likely moved southward along the Great Lakes region and eventually settled in the fertile central highlands of Kenya. Linguistic studies suggest that the Kikuyu language shares commonalities with other Bantu languages, providing evidence of their shared ancestry with groups such as the Meru, Embu, and Kamba tribes in Kenya.

This migration was not a singular event but a gradual process over centuries. Along the way, the Kikuyu adopted agricultural practices, iron-working technologies, and new cultural traits that would later define their way of life. These skills enabled them to thrive in their new environment and interact with other communities, including the Nilotic and Cushitic groups, who had also migrated into the region.

Is there acheological remains artifacts for kikuyu?

Settlement in the Central Highlands

Upon arriving in the central highlands of Kenya, the Kikuyu found a fertile and hospitable region that was ideal for their agrarian lifestyle. The highlands, with their rich volcanic soils, abundant rainfall, and moderate climate, provided excellent conditions for farming. The Kikuyu began cultivating crops such as yams, millet, and sorghum, which formed the basis of their diet and economy. They also raised livestock, including goats and sheep, as a secondary source of sustenance.

The central highlands were not only agriculturally rich but also strategically located. The region’s proximity to rivers and forests allowed the Kikuyu to develop sustainable practices for accessing water, firewood, and building materials. Over time, they cleared forests to create settlements and agricultural fields, a process that shaped the landscape and expanded their territorial claims.

As they settled, the Kikuyu organized themselves into clans based on the nine daughters of Gikuyu and Mumbi. Each clan held specific territories and responsibilities, maintaining a sense of unity while allowing for local governance. The Kikuyu society was structured around councils of elders, known as Kiama, which played a central role in resolving disputes, managing communal resources, and preserving traditions.

Interactions with Neighboring Communities

The Kikuyu did not settle in isolation. They interacted and traded with neighboring communities, including the Maasai and the Kamba. From the Maasai, they adopted certain livestock-keeping techniques and occasionally intermarried, fostering cultural exchanges. The Kamba, known for their trade networks, facilitated the exchange of goods such as iron tools, beads, and salt.

These interactions were not always peaceful, as territorial disputes occasionally arose. However, the Kikuyu’s agricultural surplus and growing population enabled them to establish dominance in the highlands, allowing them to expand their territory and influence. They developed a robust system of alliances and defense mechanisms to protect their land and way of life.

Legacy of the Migration

The Kikuyu migration and settlement in the central highlands laid the foundation for their cultural, economic, and social systems. Their deep connection to the land, rooted in the myth of Gikuyu and Mumbi, continues to shape their identity. The central highlands remain the heartland of Kikuyu culture, where traditions such as irua (initiation ceremonies) and agricultural practices are still celebrated.

This blend of mythology, historical migration, and adaptive settlement illustrates the resilience and resourcefulness of the Kikuyu people. Their history serves as a testament to their ability to thrive in new environments while preserving their cultural heritage, setting the stage for their significant role in Kenya’s broader historical narrative.

2. Social Structure and Traditions of the Kikuyu People

The Kikuyu people have a rich and intricate social structure deeply rooted in their mythology and oral traditions. Their society is built upon a strong sense of kinship, governance, and cultural continuity, making it one of the most cohesive communities in Kenya. This section delves into the foundational aspects of Kikuyu social organization, governance, and cultural practices.

The Clan System: A Legacy of Gikuyu and Mumbi

At the core of Kikuyu society is the clan system, which traces its origins to the mythological ancestors, Gikuyu and Mumbi. According to oral tradition, Gikuyu and Mumbi were blessed with nine daughters: Wanjiku, Wambui, Wangari, Waithira, Wanjiru, Nyambura, Njeri, Wangui, and Nyakairu. These daughters married and established nine clans, which became the foundation of Kikuyu identity and social organization. Although often referred to as “nine clans,” the Kikuyu culturally emphasize the number “nine plus one,” as it was considered taboo to count the exact number of living beings (Leakey, 1977, p. 2).

The clan system played a vital role in ensuring unity and cooperation within Kikuyu society. Each clan was autonomous in managing its affairs but adhered to shared traditions and beliefs that promoted collective well-being. Members of the same clan were considered kin, and intermarriage within the clan was strictly prohibited to maintain social harmony.

Traditional Governance: Councils of Elders (Kiama)

Governance among the Kikuyu was decentralized yet highly structured. The councils of elders, or Kiama, were the backbone of Kikuyu governance. These councils were responsible for settling disputes, overseeing land allocation, and conducting religious ceremonies. Elders earned their positions through wisdom, experience, and demonstrated leadership rather than heredity, ensuring that governance was rooted in merit (Leakey, 1977, p. 5).

The Kiama system operated at various levels, from local family councils to larger regional assemblies. Elders also played a significant role in initiating and supervising rites of passage, such as circumcision, which were critical to maintaining the societal order. Through the Kiama, the Kikuyu preserved their cultural values, traditions, and laws.

Roles of Men, Women, and Age-Sets

The Kikuyu social structure assigned distinct roles to men, women, and age-sets, creating a balance of responsibilities and ensuring the community’s sustainability.

- Men: Men were primarily responsible for leadership, land cultivation, and defense. They participated in councils and performed rituals and sacrifices on behalf of their families and clans. Elderly men, in particular, held significant authority within the Kiama system.

- Women: Women were the custodians of the home and family, playing a central role in child-rearing, food preparation, and maintaining household harmony. They also contributed to agricultural work, particularly in planting and harvesting crops. Women’s influence extended into spiritual practices, as they performed rituals associated with fertility and healing (Leakey, 1977, p. 3).

- Age-Sets: The Kikuyu organized society into age-sets, groups of individuals who underwent initiation rites together. These age-sets progressed through life stages, from warriors (Anake) to elders (Athuri), each with specific responsibilities and privileges. Age-sets fostered camaraderie and collective responsibility among members, ensuring that the community functioned cohesively.

Cultural Practices: Circumcision (Irua) and Marriage Rituals

The Kikuyu’s cultural practices were deeply symbolic and reinforced societal values. Two of the most significant rites were circumcision (irua) and marriage.

- Circumcision (Irua): Circumcision marked the transition from childhood to adulthood for both boys and girls in Kikuyu society. It was not only a physical procedure but also a ceremonial initiation into the community. Initiates were taught societal responsibilities, morality, and the secrets of Kikuyu traditions during this period. The ritual was accompanied by songs, dances, and blessings, emphasizing its importance as a rite of passage (Leakey, 1977, p. 1).

- Marriage Rituals: Marriage was a communal affair involving negotiations between families. The bride price, or ruracio, was an essential part of the process, symbolizing the union of two families rather than just two individuals. The Kikuyu viewed marriage as a sacred institution central to the continuity of the family and clan. Polygamy was common, especially among wealthy men, as it was seen as a way to expand one’s family and labor force (Leakey, 1977, p. 7).

3. Economic Activities of the Kikuyu

The Kikuyu were predominantly agriculturalists, with their livelihoods intricately tied to the land. Both Kenyatta (1938) and Leakey (1977) highlight that farming was not merely an economic activity for the Kikuyu but also a cultural and spiritual practice, deeply rooted in their connection to the land.

Traditional Subsistence Farming

Kikuyu agricultural practices revolved around the cultivation of staple crops such as yams, bananas, millet, and later, maize and beans. Kenyatta (1938) describes how each family maintained its plot of land, known as githaka, which was considered sacred and passed down through generations. The Kikuyu saw land as a divine gift from Ngai (God), and its care and productivity were central to their way of life.

Leakey (1977) further notes that the Kikuyu developed advanced farming techniques to adapt to the hilly terrain of the central highlands. Terracing was a common practice, preventing soil erosion and ensuring sustainable farming. Communal labor was another cornerstone of their agricultural economy; neighbors would assist each other during planting and harvesting seasons, strengthening social bonds and ensuring collective food security.

Role as Agricultural Innovators

The Kikuyu were known for their resourcefulness and innovation in farming. According to Leakey (1977), they employed crop rotation methods to maintain soil fertility and prevent pest infestations. They also cultivated specific plant species in harmony with the environment, utilizing indigenous knowledge to maximize productivity. Their practices included planting fast-growing crops alongside slower-maturing ones, ensuring a consistent food supply throughout the year.

In addition to crops, the Kikuyu raised livestock, including goats, sheep, and chickens. Livestock served multiple purposes, from providing manure for fertilization to being used in trade and rituals.

Trade Relationships with Neighboring Communities

Trade was another critical component of the Kikuyu economy. The Kikuyu engaged in barter with neighboring communities, such as the Maasai, Kamba, and Embu. They traded agricultural produce like grains, bananas, and sugarcane for Maasai livestock, milk, and hides. Leakey (1977) notes that these trade relationships were marked by both mutual benefit and occasional conflict over resources and territorial boundaries.

The Kikuyu’s agricultural surplus allowed them to dominate regional trade, and their strategic settlements near trade routes ensured access to essential goods from distant regions. They also produced items such as pottery, iron tools, and woven baskets, which were exchanged within and beyond their communities.

Economic and Spiritual Relationship with the Land

For the Kikuyu, land was more than just a resource; it was the essence of their cultural identity. Kenyatta (1938) explains that the land was viewed as a sacred trust from Ngai, to be preserved for future generations. This spiritual connection drove the Kikuyu to adopt sustainable practices that ensured the long-term productivity of their land. Rituals were performed to honor the land, particularly during planting and harvest seasons, to seek blessings for bountiful yields.

Leakey (1977) adds that the Kikuyu’s communal land ownership system reflected their belief in collective responsibility. While individual families cultivated specific plots, the broader community retained authority over the allocation and use of land, ensuring fairness and preventing exploitation.

4. Spiritual Beliefs and Religion

Traditional Spirituality and Sacred Sites

The Kikuyu people’s spirituality is centered on the worship of Ngai, the Supreme God, believed to reside on Mount Kirinyaga (Mount Kenya). Ngai is considered a benevolent deity who blesses the land and its people, and prayers and offerings are made to seek guidance, blessings, or forgiveness. Sacred sites such as Mukurwe wa Nyagathanga, the mythological home of Gikuyu and Mumbi, hold profound spiritual and cultural significance (Muriuki, 1969, pp. 136–140).

Leakey (1977) describes the sacred fig tree (mugumo) as a vital element in Kikuyu spirituality. These trees were considered gateways to the divine, where rituals and sacrifices were performed. Communities gathered under the mugumo to pray, consult elders, or conduct ceremonies to honor Ngai and ask for rain, protection, or healing. These rituals reflected a deep respect for nature, seen as a manifestation of divine power.

Kenyatta (1938) emphasizes that the Kikuyu’s relationship with the land was inherently spiritual, as they believed Ngai gifted the land to their ancestors. Ceremonies linked to the agricultural cycle, such as planting and harvest, were conducted to honor this connection and express gratitude to Ngai.

Prophets, Seers, and Rituals

The Kikuyu held prophets (arathi) and seers in high regard. These individuals were considered intermediaries between Ngai and the community, often predicting future events or providing guidance during crises. Leakey (1977) notes that seers played crucial roles during periods of drought, famine, or conflict, leading rituals to cleanse the community or seek divine intervention. Their visions were treated with reverence, as they were believed to reflect Ngai’s will.

Rituals were central to Kikuyu spirituality, often involving offerings of goats, sheep, or other valuable items. These ceremonies sought to maintain harmony between the people and their deity. Kenyatta (1938) highlights the importance of communal participation in these rituals, reinforcing social cohesion and shared moral values. Circumcision ceremonies, for instance, were both spiritual and social events, marking an individual’s transition to adulthood under Ngai’s blessing.

Impact of Christian Missionary Work

The arrival of Christian missionaries in the late 19th and early 20th centuries introduced significant changes to Kikuyu spirituality. Many Kikuyu converted to Christianity, drawn by the promise of education and new opportunities. However, this conversion often came with tension, as traditional practices were dismissed as pagan or backward.

Muriuki (1969) notes that while Christianity challenged Kikuyu traditions, it did not erase them entirely. Many Kikuyu blended Christian practices with their indigenous beliefs, maintaining rituals such as prayers under the mugumo tree alongside church worship. Leakey (1977) observed that the spiritual significance of Mount Kirinyaga persisted, even among Christian Kikuyu, as a symbol of divine connection.

Kenyatta (1938) argued that the imposition of Christianity disrupted Kikuyu cultural identity, particularly through the rejection of traditional rites such as circumcision. He viewed this as a colonial strategy to undermine the unity and resilience of the Kikuyu people. Despite this, the Kikuyu demonstrated remarkable adaptability, creating a syncretic spirituality that honored both their ancestral traditions and newfound faith.

5. Kikuyu during Colonial Period

Land Alienation Policies and Their Impact

The British colonial rule dramatically reshaped the Kikuyu’s relationship with their ancestral lands. Large swathes of Kikuyu land were alienated for European settlers, particularly in Kiambu, leaving many Kikuyu families as tenant farmers. According to Tignor, this process turned once-independent landowners into an agricultural proletariat. The forced displacement and loss of land were key catalysts for Kikuyu resentment, planting the seeds for later resistance movements (Tignor, 1976, pp. 15-19).

Kikuyu Labor in Colonial Industries

The Kikuyu provided a substantial labor force for colonial projects, especially in coffee farming. These industries required large numbers of workers, but wages remained exploitative, forcing many Kikuyu into poverty. Tignor describes this exploitation as a defining feature of Kikuyu colonial experiences, with the community disproportionately burdened by low wages and harsh working conditions (Tignor, 1976, pp. 186-188).

Resistance Movements and Kikuyu Central Association

Resistance to colonial rule found organized expression through groups like the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA). Founded in the 1920s, the KCA became a hub for advocating land rights, education, and cultural preservation. It marked the beginning of a broader anti-colonial struggle that would eventually culminate in the Mau Mau movement.

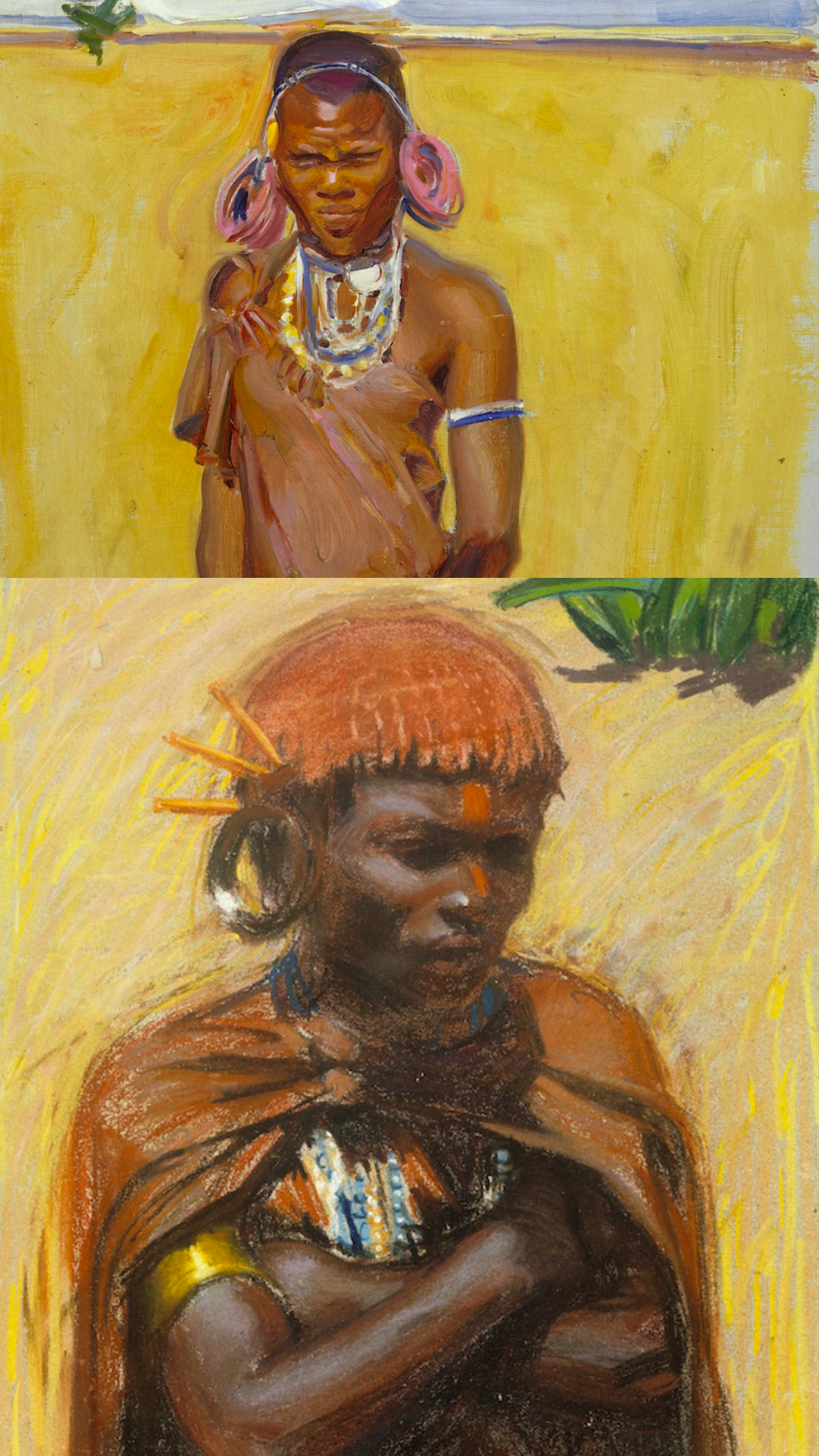

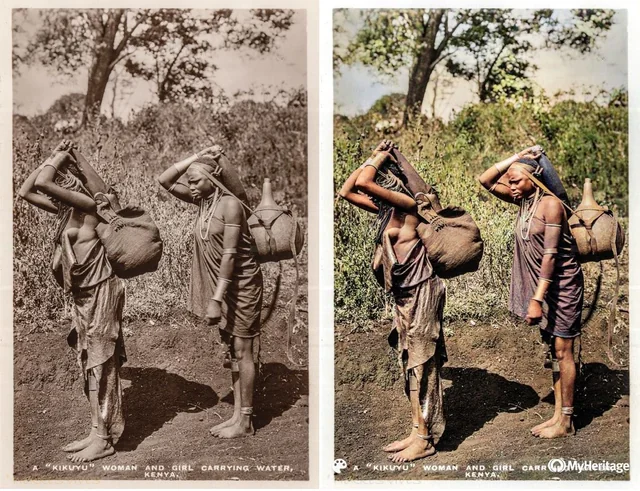

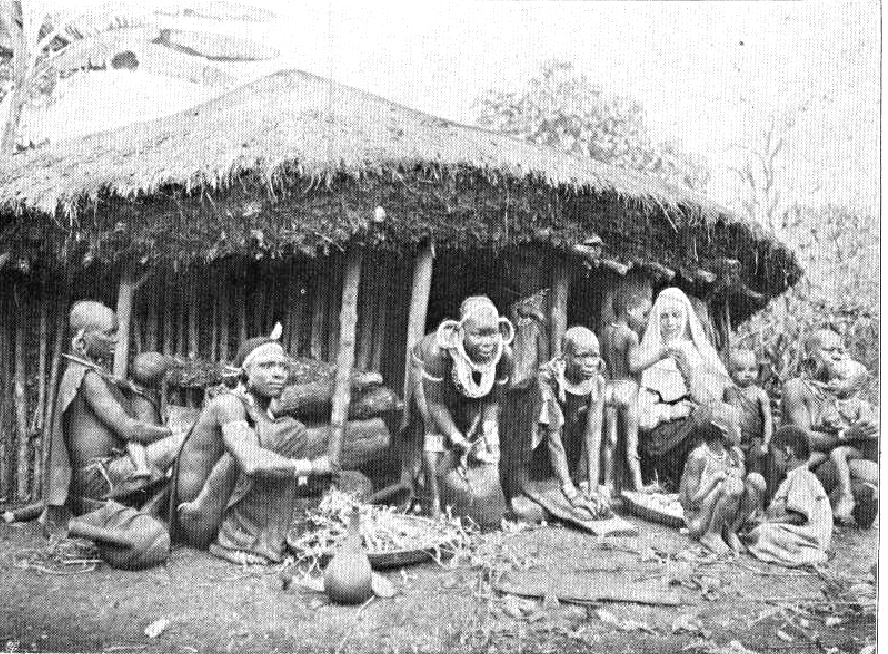

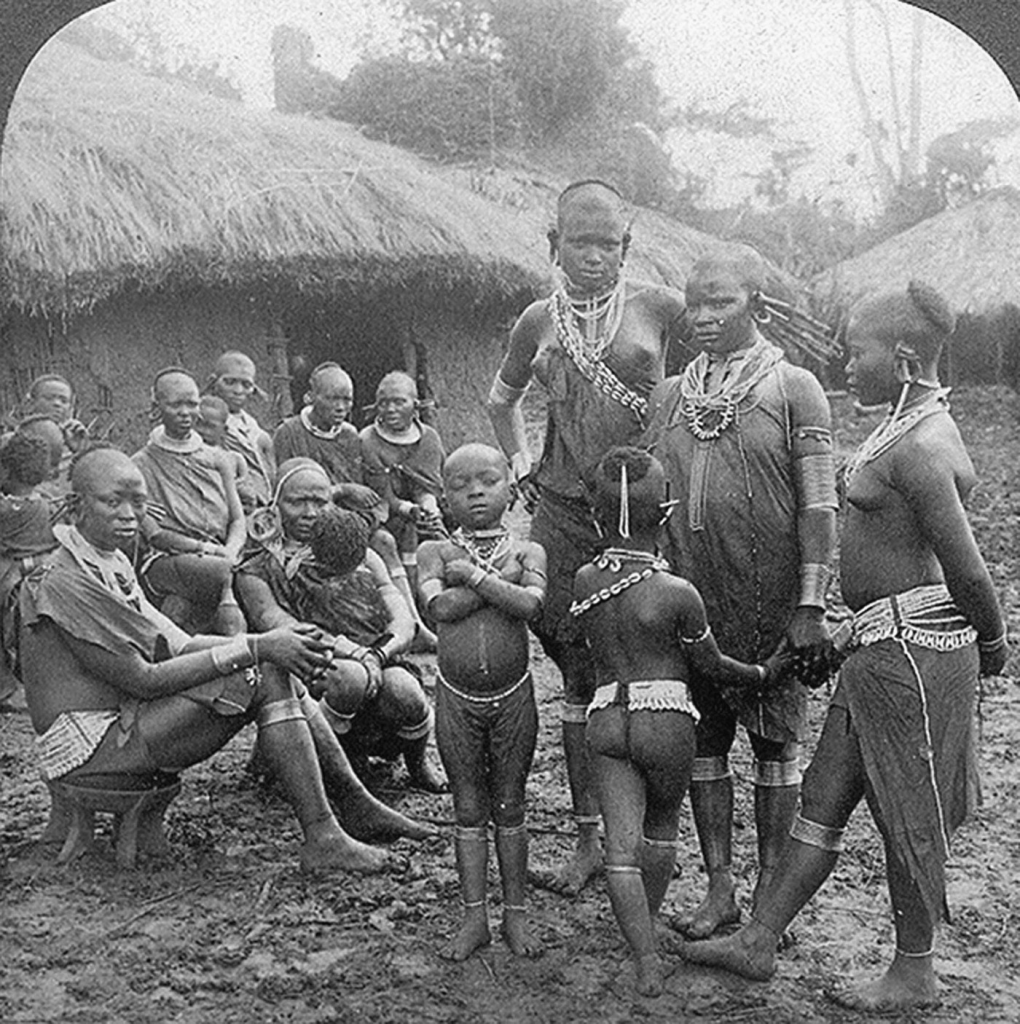

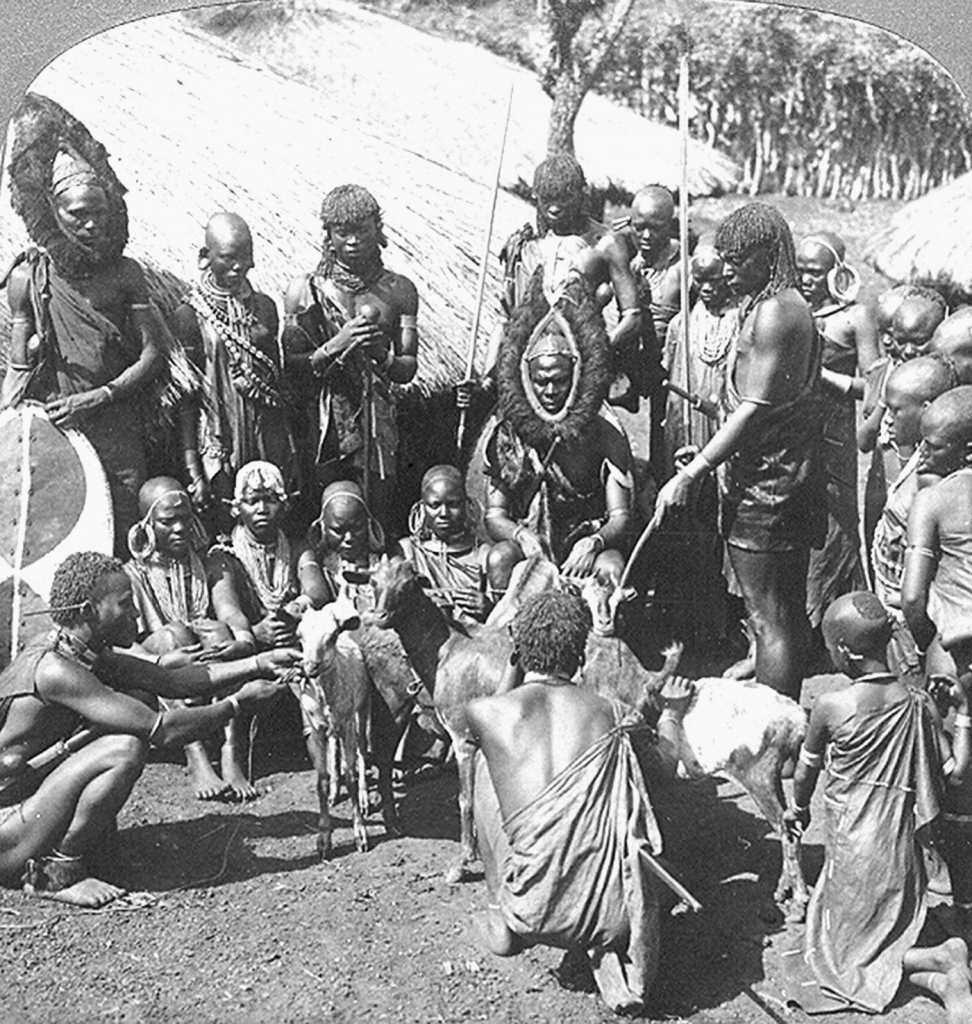

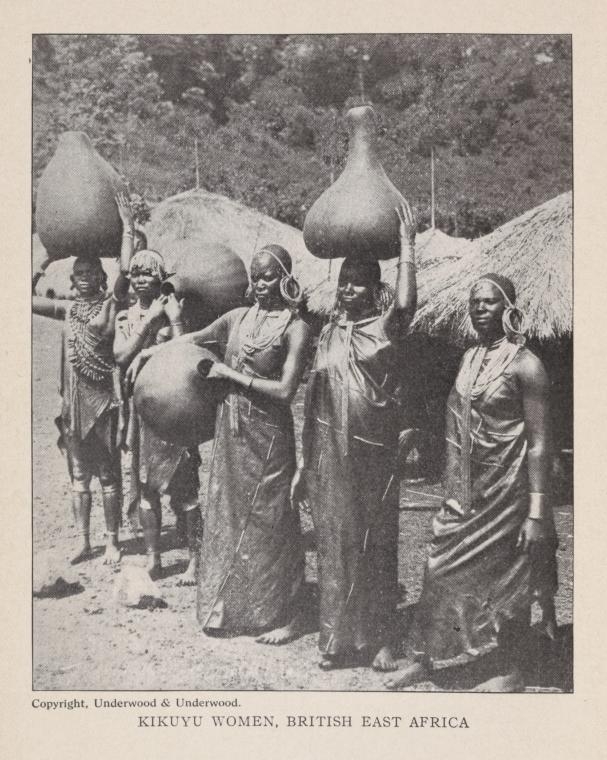

20th century kikuyu people in pictures

Images of the Kikuyu and their way of life were among the first representations of African communities to reach Western audiences. Stereoscopic photographs taken in the early 20th century portrayed Kikuyu chiefs, their families, and traditional village settings. These images, while often exoticized, provided a rare glimpse into pre-colonial Kikuyu society and inadvertently documented early colonial impacts. For example, Wambugu wa Mathangani, a prominent Kikuyu chief, was photographed with his family in regalia meant to signify wealth and status, reflecting the complex interplay between Kikuyu tradition and colonial representation (Muriuki & Sobania, 2007, pp. 1-5).

https://twitter.com/i/status/1846123034098143644

The Mau Mau Uprising

The Mau Mau Uprising, occurring between 1952 and 1960, was a pivotal movement in Kenya’s fight for independence. It emerged from the Kikuyu people’s long-standing grievances against colonial exploitation, land alienation, and political exclusion. The uprising remains a powerful symbol of resistance and determination in Kenyan history.

Causes of the Mau Mau Uprising

- Land Alienation Policies

The Kikuyu were systematically displaced from their ancestral lands, particularly in the fertile “White Highlands,” which were reserved for European settlers. By the 1940s, many Kikuyu had become squatters or landless laborers, dependent on colonial farms (Tignor, 1976, pp. 15-18). This economic dispossession created a deep sense of injustice, fueling resistance. - Economic Exploitation

The colonial economy relied heavily on Kikuyu labor, particularly in coffee and tea plantations. However, wages were meager, and working conditions were exploitative. Many Kikuyu families faced poverty despite contributing significantly to the colony’s wealth (Barnett & Njama, 1966, pp. 37-40). - Political Exclusion

The colonial government restricted African political organizations, limiting their ability to seek reforms. Attempts to address grievances through groups like the Kenya African Union (KAU) were thwarted, leaving many Kikuyu feeling voiceless and marginalized (Kariuki, 1963, pp. 24-26).

Key Figures and Their Contributions

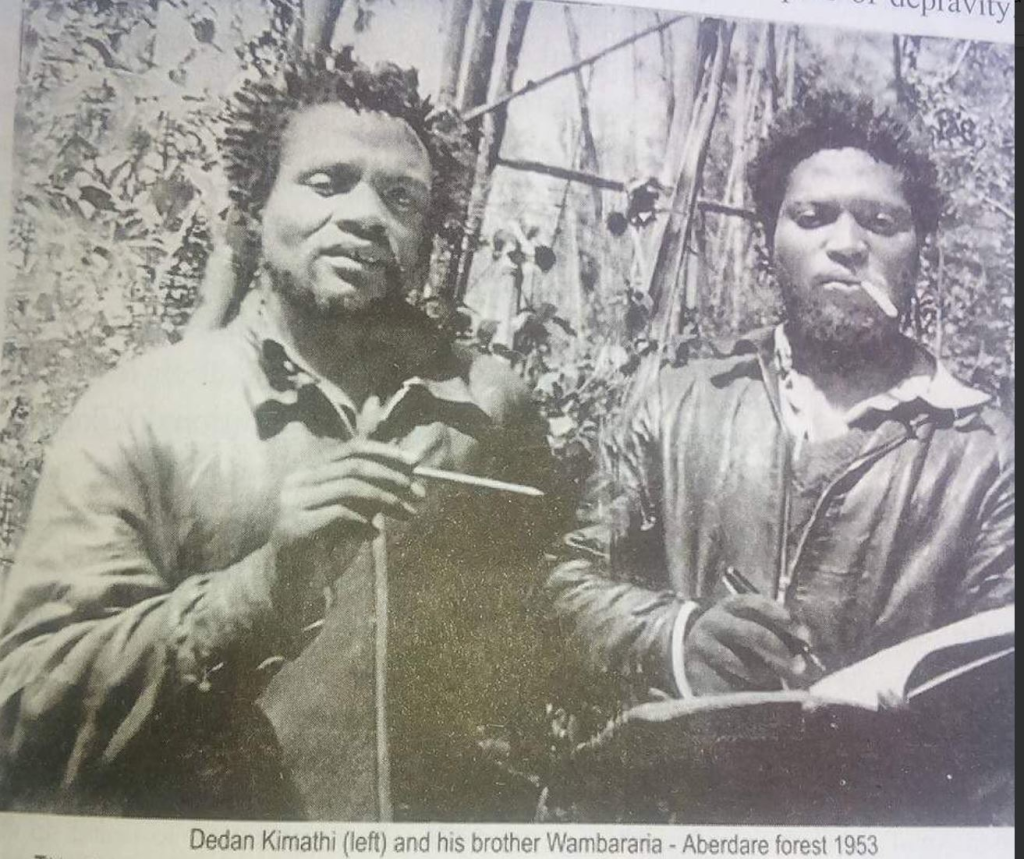

Dedan Kimathi

Dedan Kimathi, leader of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA), was instrumental in organizing guerrilla warfare against colonial forces. Operating from the Aberdare and Mount Kenya forests, Kimathi’s leadership inspired fighters to persist despite overwhelming challenges. His commitment to the cause made him a symbol of Kenyan resistance. His capture and execution by colonial authorities further cemented his legacy as a martyr for Kenyan independence (Ngugi & Mugo, 1976, pp. 45-50).

Karari Njama

Karari Njama, a Mau Mau fighter and chronicler, documented the rebellion’s strategies and hardships. His work provided a vital counter-narrative to colonial propaganda, offering a detailed and humanized view of the Mau Mau struggle. His book Mau Mau from Within remains a key historical record of the movement (Barnett & Njama, 1966, pp. 67-70).

J.M. Kariuki

J.M. Kariuki, a former detainee, shed light on the brutal conditions in detention camps through his memoir Mau Mau Detainee. His account exposed the human rights abuses inflicted on Kikuyu suspects, galvanizing both local and international opposition to colonial practices. Kariuki’s later political career as a Member of Parliament made him a voice for those who had suffered under colonial rule (Kariuki, 1963, pp. 112-115).

General China (Waruhiu Itote)

General China, whose real name was Waruhiu Itote, was one of the most prominent military leaders of the Mau Mau. Captured by the British in 1954, he later cooperated with the colonial government to write his memoir, Mau Mau General, offering insight into the movement’s operations. Despite controversy over his collaboration after capture, his military strategies were critical during the rebellion’s early phases (Itote, 1967, pp. 15-20).

Stanley Mathenge

Stanley Mathenge led significant groups of Mau Mau fighters in the Mount Kenya region. Known for his discipline and tactical planning, Mathenge’s leadership contributed to some of the rebellion’s most successful operations. Though he reportedly fled to Ethiopia later in the struggle, his role remains a critical part of Mau Mau history (Barnett & Njama, 1966, pp. 80-85).

General Kahiu-Itina

General Kahiu-Itina was another key leader operating in the Aberdare forests. His leadership in logistical planning and supply chain management helped sustain the fighters. Kahiu-Itina’s contributions to the rebellion are often overshadowed by Kimathi’s prominence but remain vital to the movement’s overall success (Kinyatti, 1980, pp. 50-53).

General Kĩhĩhĩo

General Kĩhĩhĩo, a notable field commander, was instrumental in maintaining morale among the fighters. His leadership ensured coordination between various Mau Mau factions. Though less widely recognized than Kimathi or Mathenge, Kĩhĩhĩo played a pivotal role in tactical operations and inspiring resistance (Kinyatti, 1980, pp. 53-55).

Women in the Mau Mau

Women such as Wambui Otieno and Field Marshal Muthoni were indispensable to the rebellion. Wambui Otieno served as a courier and spy, while Field Marshal Muthoni fought alongside men in the forests. Women often took on dual roles, managing logistics and aiding guerrilla fighters, despite the extreme dangers they faced (Barnett & Njama, 1966, pp. 90-95).

Impact on the Kikuyu Community

- Forced Relocations and Detention Camps

To suppress the rebellion, colonial authorities established emergency villages, forcibly relocating thousands of Kikuyu. Detention camps subjected suspected Mau Mau sympathizers to inhumane conditions, including torture and forced labor (Kariuki, 1963, pp. 87-90). - Cultural Disruption

The rebellion disrupted Kikuyu traditions, as sacred forests became battlegrounds and communal structures were dismantled. Barnett and Njama (1966) describe how these upheavals fundamentally altered the Kikuyu way of life (pp. 95-97). - Path to Independence

Despite the suffering, the uprising pressured the British government to reconsider its colonial policies. The rebellion exposed the unsustainability of British rule, ultimately paving the way for Kenya’s independence in 1963 (Tignor, 1976, pp. 180-183).

7. Post-Independence Role of the Kikuyu

The Kikuyu have played a central role in Kenya’s political, social, and economic development since the country gained independence in 1963. As the largest ethnic group in Kenya, their influence has been significant, often serving as a cornerstone in shaping the nation’s trajectory.

Political Dominance Under Jomo Kenyatta

Jomo Kenyatta, Kenya’s first President and a prominent Kikuyu leader, symbolized the Kikuyu’s prominence in post-independence Kenya. Kenyatta’s presidency (1963–1978) established policies that prioritized economic growth, infrastructure development, and education. However, his leadership was also marked by land allocation controversies, with large tracts of formerly European-owned land being redistributed disproportionately to Kikuyu elites (Tignor, 1976, pp. 210–215). This contributed to the group’s political and economic influence but also sparked resentment among other communities.

During Kenyatta’s presidency, the Kikuyu consolidated their power in political institutions, becoming dominant in the ruling party, the Kenya African National Union (KANU). This control extended to key government ministries and the civil service, further cementing their leadership in the newly independent state (Kariuki, 1963, pp. 185–190).

Economic and Social Development

The Kikuyu’s entrepreneurial spirit, honed over centuries of agricultural innovation, carried into the post-independence era. Many Kikuyu ventured into commerce, agriculture, and real estate, playing a significant role in building Nairobi as East Africa’s largest business hub. Kikuyu traders and industrialists became leaders in sectors such as retail, manufacturing, and banking (Barnett & Njama, 1966, pp. 190–195).

Socially, the Kikuyu emphasized education as a pathway to success. This led to a high rate of school enrollment and the emergence of Kikuyu professionals in fields such as law, medicine, and education. The Kikuyu’s cultural emphasis on self-reliance and cooperation underpinned their economic successes, even as Kenya faced broader developmental challenges (Tignor, 1976, pp. 235–240).

Tensions and Challenges

Despite their achievements, the Kikuyu’s prominence has not been without challenges.

- Land Issues

Land redistribution under Kenyatta disproportionately benefited Kikuyu elites, creating discontent among landless Kikuyu and other ethnic groups. The allocation of land in areas such as the Rift Valley became a source of inter-ethnic tension, especially between the Kikuyu and the Kalenjin. These tensions would later erupt during politically charged periods, such as the post-election violence of 2007–2008 (Barnett & Njama, 1966, pp. 215–220). - Inter-Ethnic Relations

The perception of Kikuyu dominance in politics and the economy has fueled friction with other communities. Accusations of nepotism and favoritism have occasionally alienated other ethnic groups, contributing to cycles of ethnic-based political competition and violence (Kinyatti, 1980, pp. 130–135). - Internal Inequalities

Within the Kikuyu community, disparities between wealthy elites and the rural poor have created internal divisions. While a few benefited from post-independence policies, many Kikuyu remained landless or struggled to access opportunities.

Enduring Legacy

The Kikuyu have remained influential in Kenya’s political landscape even after Kenyatta’s presidency. Leaders such as Mwai Kibaki, another Kikuyu, served as Kenya’s President from 2003 to 2013. Kibaki’s leadership focused on economic reforms, infrastructure, and education, further cementing the Kikuyu’s reputation for development-oriented leadership (Tignor, 1976, pp. 260–265).

The Kikuyu’s resilience, adaptability, and resourcefulness have ensured their continued prominence in Kenya’s national story. Despite facing challenges, they have played an indispensable role in shaping Kenya’s identity as a modern, independent nation.

8. Modern Kikuyu Culture

The Kikuyu people have successfully preserved many aspects of their traditions while adapting to the dynamic changes brought by modernity. This balance is reflected in their cultural practices, language, and contributions to Kenya’s socio-economic fabric.

Preservation of Traditions

Kikuyu traditions, such as the practice of oral storytelling, continue to play a vital role in passing down cultural values and history. Elders still recount tales of Gikuyu and Mumbi, using them to instill a sense of identity and purpose in younger generations. Traditional ceremonies, such as circumcision (irua), have been adapted to suit modern contexts, often taking place in controlled environments rather than communal settings.

The Kikuyu naming system, based on a generational cycle and lineage, remains a significant cultural practice. Names carry deep meanings and connect individuals to their ancestry, preserving a spiritual connection to their heritage.

Role of Language, Music, and Storytelling

Gĩkũyũ, the Kikuyu language, is a critical tool for cultural preservation. Despite the dominance of English and Swahili in Kenya, efforts to teach Gĩkũyũ in schools and use it in media have helped sustain the language. Music, especially the popularity of Kikuyu gospel and benga genres, has become a vibrant medium for storytelling and cultural expression. Artists like Joseph Kamaru and contemporary musicians continue to highlight Kikuyu heritage through their lyrics and melodies.

Modern Kikuyu authors, such as Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o, have championed the importance of writing in indigenous languages, promoting cultural pride and resistance against cultural erasure. His works, including The River Between and Devil on the Cross, explore Kikuyu struggles and resilience.

Prominent Kikuyu Personalities

The Kikuyu community has produced numerous influential figures across various fields. In politics, leaders like former President Mwai Kibaki and business magnates like James Mwangi of Equity Bank showcase their leadership and entrepreneurial spirit. In the arts, Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o continues to inspire generations, while figures like Esther Wahome represent Kikuyu excellence in music. In sports, athletes like Catherine Ndereba have brought international recognition to Kenya.

9. Challenges Facing the Kikuyu People

The Kikuyu people, like many other Kenyan communities, face contemporary challenges that test their adaptability and cohesion.

Land Ownership Disputes

Land remains a contentious issue for the Kikuyu. Historical grievances from colonial land alienation and subsequent unequal redistribution continue to fuel tensions. In regions like the Rift Valley, inter-ethnic disputes over land ownership have led to periodic violence, exacerbated during politically charged times.

Effects of Globalization

Globalization has influenced traditional Kikuyu practices, creating a tension between preserving cultural identity and embracing modernity. Urbanization and the adoption of Western lifestyles have reduced the role of traditional rites of passage and communal ceremonies. Language is also at risk, as younger generations increasingly prefer English and Swahili over Gĩkũyũ.

Political Dynamics and Representation

The Kikuyu’s historical prominence in Kenyan politics has occasionally caused friction with other communities. Accusations of favoritism and ethnic bloc voting have contributed to political polarization. As Kenya’s political landscape evolves, the Kikuyu face the challenge of navigating inter-ethnic relations while maintaining their influence.

popular Figures in Kikuyu History

Wangari Maathai

Wangari Maathai, the first African woman to receive the Nobel Peace Prize, was an environmentalist and human rights activist. Through the Green Belt Movement, she mobilized communities to plant millions of trees, combat deforestation, and advocate for sustainable development. Maathai’s Kikuyu heritage inspired her commitment to the land and its preservation, linking environmental conservation with social justice (Maathai, 2004, pp. 78-82).

Other popular kikuyu people

- Dedan Kimathi Waciuri

- Leader of the Mau Mau rebellion and a symbol of Kenyan resistance during the fight for independence.

- Jomo Kenyatta

- The first President of Kenya, instrumental in the anti-colonial struggle, and an advocate for Kikuyu cultural preservation through works like Facing Mount Kenya.

- Waiyaki wa Hinga

- A 19th-century Kikuyu leader who resisted British colonial encroachment before being captured and exiled by the British.

- Harry Thuku

- A pioneer of African nationalism in Kenya and founder of the Young Kikuyu Association, which later evolved into the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA).

- General China (Waruhiu Itote)

- A senior Mau Mau commander who negotiated for peace talks with the colonial government.

- Field Marshal Muthoni Kirima

- The highest-ranking female fighter in the Mau Mau, remembered for her leadership and courage during the rebellion.

- Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o

- An internationally renowned writer and cultural activist who has championed the preservation of Kikuyu language and literature.

- Koinange wa Mbiyũ

- A senior Kikuyu elder and advisor to Jomo Kenyatta, instrumental in fostering Kikuyu unity during the independence era.

- Joseph Murumbi

- Kenya’s second Vice President, known for his role in independence negotiations and his advocacy for cultural preservation.

- Mary Nyanjiru

- A freedom fighter remembered for leading a women’s protest during the arrest of Harry Thuku.

- Karari Njama

- A chronicler of the Mau Mau rebellion whose writings provide invaluable insights into the struggle for freedom.

- Josiah Mwangi Kariuki (J.M. Kariuki)

- A post-independence politician and vocal critic of government corruption, whose assassination became a rallying point for calls for justice.

- James Mwangi

- A modern business magnate and CEO of Equity Bank, who has transformed banking in Kenya and provided access to financial services for millions.

- Waruhiu wa Kung’u

- A key Mau Mau strategist and military leader who played a significant role in coordinating resistance efforts in the forests

Famous Kikuyu Proverbs and Their Meanings

- “Mũtumia ũtari mwana ndanũkaga nguo”

(A woman without a child does not wash her clothes often.)- This proverb emphasizes the social value placed on children and their role in family continuity.

- “Mũrimũ wa mwĩrĩ ũrĩa wandũkĩte tondũ ya ũrimũ wa ngoro.”

(A disease of the body is easier to treat than a disease of the heart.)- Reflects the Kikuyu belief in the importance of emotional and spiritual well-being over physical health.

- “Mũũndũ ũtanyua nĩkĩ? Mũrĩrĩkĩa nĩ kũrĩtũa.”

(What does a person who never drinks taste? Life is for tasting.)- Encourages experiencing life fully and embracing its offerings.

- “Kiura gĩtirĩ mwene.”

(The rain does not have an owner.)- Symbolizes communal sharing of resources and the natural order.

- “Wega wa mũndũ ũrĩaga mũndũ.”

(A person’s kindness benefits another person.)- Highlights the importance of goodwill and mutual assistance in society.

Conclusion

The Kikuyu story is one of resilience, adaptability, and cultural richness. From their early days as agricultural innovators to their leadership in Kenya’s independence movement, the Kikuyu have demonstrated an extraordinary ability to navigate challenges and embrace opportunities. Their contributions to Kenya’s political, social, and economic development underscore their pivotal role in shaping the nation’s identity.

Despite contemporary challenges, the Kikuyu’s enduring traditions, entrepreneurial spirit, and commitment to education continue to inspire progress. As Kenya evolves, so too does the Kikuyu community, preserving their heritage while adapting to modern realities.

The Kikuyu story is one of endurance, innovation, and an unwavering connection to their heritage, shaping not just their community but the entire nation of Kenya.

References and Citations

- This article was informed by the following resources

- The Kikuyu (also Agĩkũyũ/Gĩkũyũ) are a Bantu ethnic group native to East Africa Central Kenya. At a population of 8,148,668 as of 2019, they account for 17.13% of the total population of Kenya, making them Kenya’s largest ethnic group. wikipedia

- Baganda in Uganda

- Each of the girls took a mate who was her height. Wamuyu was left to stay without a husband as she was too young to marry. These nine couples went on to establish their own homesteads and are the source, together with Wamuyu of the Nine plus One Gikuyu clans. source

- A British visitor to a Kikuyu village, early in the twentieth century, asked a mother how many children she had. “Come and see,” was her evasive reply. see Counting Taboos

- Evidence suggests that they moved across the continent sometime between 2000 BCE and 1000 CE. By about 1200 CE, they had a cultural and technological network across the trunk (center) of Africa. Bantu expansion reached almost all the way to the southern tip of the continent. The result was a web of trade, cultural exchange, and shared technology.source

- Leakey, L. S. B. (1977). The Southern Kikuyu Before 1903. Academic Press.

- Kenyatta, J. (1938). Facing Mount Kenya: The Tribal Life of the Gikuyu. London: Secker & Warburg.

- Muriuki, G. (1969). A history of the Kikuyu to 1904. University of London.

- Muriuki, G., & Sobania, N. (2007). The Truth Be Told: Stereoscopic Photographs, Interviews, and Oral Tradition from Mount Kenya. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 1(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/17531050701218783.

- Tignor, R. L. (1976). The Colonial Transformation of Kenya: The Kamba, Kikuyu, and Maasai from 1900-1939. Princeton University Press.

- Barnett, D. L., & Njama, K. (1966). Mau Mau from Within: An Analysis of Kenya’s Peasant Revolt. Nairobi: East African Publishing House.

- Kariuki, J. M. (1963). ‘Mau Mau Detainee’: The Account by a Kenya African of His Experiences in Detention Camps, 1953–1960. Nairobi: Oxford University Press.

- Kinyatti, M. (1980). Agĩkũyũ, 1890-1965 Waiyaki. Kenyatta. Kĩmaathi. Nairobi: Kenya Literature Bureau.

- Maathai, W. (2004). Unbowed: A Memoir. Alfred A. Knopf.