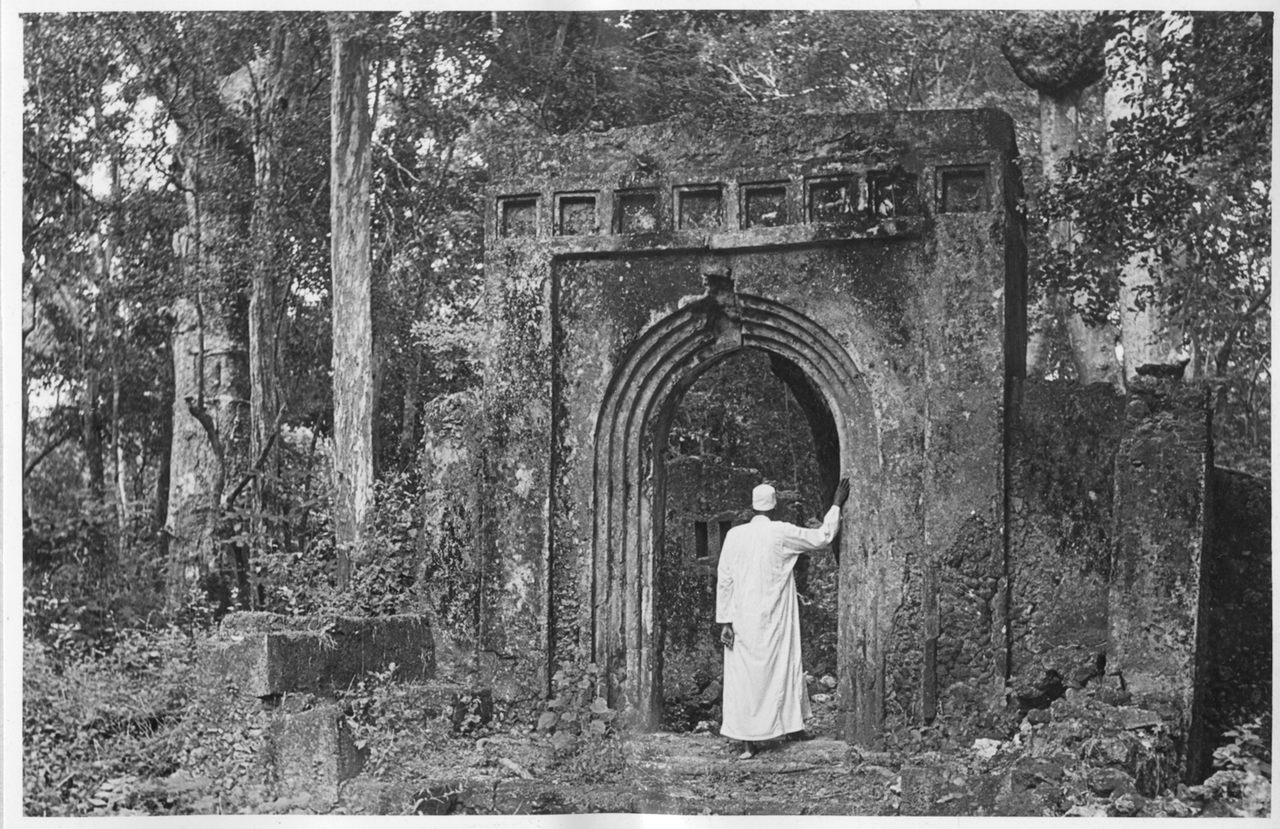

In 1948, Dr. James Kirkman, a university archaeologist, embarked on a journey to uncover the secrets of Gede, an ancient Swahili city buried in the dense coastal bush and sand of Kenya. This city, likely inhabited from the late 13th century and abandoned for around 300 years, was a once-thriving Islamic metropolis. Spanning 45 acres, Gede was enclosed by two stone walls and featured a fort, numerous stone buildings, a grand Friday mosque, pillared tombs, and an ornate palace with a council chamber. Kirkman unearthed artifacts from as far as Venice and China, revealing Gede’s extensive trade networks.

Gede’s inland location is a mystery, as most Swahili cities were built near the sea or on islands. Its abandonment and subsequent disappearance from historical records, including Portuguese accounts, add to the enigma. Rediscovered in 1884 by Sir John Kirk and later declared a national park, Gede has since revealed a sophisticated, cultured, and highly religious civilization, challenging the Victorian notion of Africa as the “Dark Continent.”

The Swahili Coast: A Hub of Ancient Trade and Culture

The Bantu Influence and the Rise of Swahili Civilization

The Swahili civilization emerged from the interaction between Bantu pastoralists and Arab and Persian traders. The Bantu, who migrated across central and western Africa, brought ironworking skills to the coast, enabling the development of permanent settlements. These settlements, initially temporary, evolved into thriving towns engaged in intercontinental trade.

The Lamu Archipelago: The Cradle of Swahili Civilization

The Lamu Archipelago, off the northern coast of Kenya, is believed to be the earliest extensively settled part of the Swahili coast. Excavations at Shanga, the oldest known site, suggest it was founded in the mid-8th century by Bantu pastoralists. Similarly, Manda Town, dated to around 800 AD, and Unguja Ukuu on Zanzibar Island, with artifacts from the 9th century, highlight the region’s early development.

The Foundation Tales: Myths and Realities of Swahili Origins

The Chronicles of Abdul Malik and the Islamic Expansion

Swahili chronicles often attribute the founding of coastal towns to Abdul Malik, the ninth Islamic caliph (685-705 AD). According to the Pate Chronicle, Abdul Malik sent Syrians to build cities like Pate, Malindi, Zanzibar, Mombasa, Lamu, and Kilwa. These tales, while entertaining, are likely embellished to lend prestige to the towns, much like early Christian churches claiming apostolic foundations.

The Exiles and the Lure of Gold

Other chronicles tell of Islamic heretics and outcasts fleeing persecution in the Middle East. The Chronicle of Kilwa recounts the story of Ali bin Hasan, a Persian prince who bought Kilwa Island with cloth and established a new kingdom. These tales, though contradictory, reflect the complex interplay of migration, trade, and cultural exchange that shaped the Swahili coast.

The First Swahili Towns: Settlements and Trade

The Importance of Fresh Water and Strategic Locations

Settlement on small islands or on the seafront is entirely dependent on the ability of its inhabitants to construct wells in order to extract fresh water from the ground. Otherwise, settlements have to be located beside rivers at a point above the high tide mark for fresh water to be available. There is evidence that mainland settlements did exist before those on islands and near beaches. Rhapta, which Ptolemy said was “set back a little from the sea”, is a possible example. Pottery remains dated to the ninth century have been unearthed in the delta of the Tana River, including finds at a settlement called Ungwana, situated on a raised beach beside a tributary of the Tana River. However, the ability of towns lying a short distance inland to carry out international maritime trade is limited and fails to take advantage of such natural geographical features as beaches, deep harbours and estuaries. Seafront settlement, particularly on islands, was therefore a revolutionary step forward.

The Lamu Archipelago: A Cluster of Ancient Towns

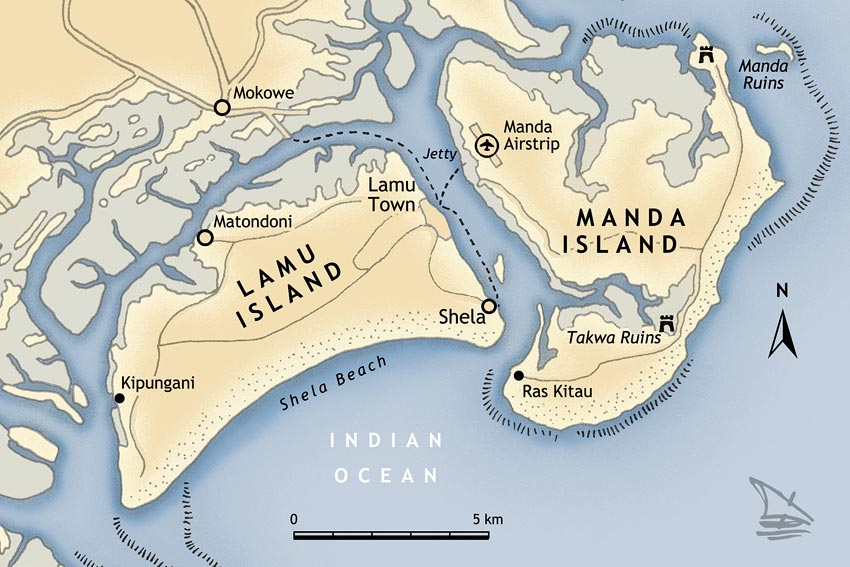

Archaeology now suggests that the earliest part of the Swahili coast to be extensively settled was the Lamu Archipelago, a cluster of hot, low-lying, desert islands off the extreme northern coast of Kenya. The sand dunes here no doubt conceal many more secrets, but the work done so far on the three main islands of Lamu, Manda and Pate suggest that at least eight towns existed here more than a thousand years ago.

In 1980, the Cambridge archaeologist, Mark Horton, began the first in a series of six excavations at Shanga, a now-ruined, stone town on the southern shore of Pate Island. It is the oldest site known on the coast and possibly the first to make use of wells. Shanga was probably founded in the middle of the eighth century by Bantu pastoralists who saw trade with the Arabs and Persians as a lucrative, alternative source of income, possibly because of a prolonged drought which had made their previous lifestyle less tenable. Shanga may well have been a temporary settlement at first, inhabited when traders arrived on the north-east monsoon, abandoned when traders returned to the Middle East when the monsoon winds changed direction.

Before Horton’s work in the 1980s, the oldest known settlement was Manda Town, a site on the northern tip of nearby Manda Island. This had been excavated by the then Director of the British Institute of Eastern Africa, Neville Chittick, in 1966, who identified the site as dating from 800AD due to pottery and Chinese porcelain dated to the ninth century. Again, Manda is likely to have been settled on the same temporary basis as Shanga.

The oldest site known outside the Lamu Archipelago, apart from the mainland site of Ungwana, is the town of Unguja Ukuu, the old capital of Zanzibar Island, located seventeen miles south-east of the modern capital. In 1865, a horde of 500 Middle Eastern coins was unearthed there, with one dated as early as 794. In 1965, Neville Chittick uncovered some shards of Islamic pottery and, after comparing his finds with pottery manufactured in the Middle East, Chittick was able to date the pottery, and therefore the site, to the ninth century.

The Foundation Tales: Myths and Realities of Swahili Origins

The Chronicles of Abdul Malik and the Islamic Expansion

Swahili chronicles often attribute the founding of coastal towns to Abdul Malik, the ninth Islamic caliph (685-705 AD). According to the Pate Chronicle, Abdul Malik sent Syrians to build cities like Pate, Malindi, Zanzibar, Mombasa, Lamu, and Kilwa. These tales, while entertaining, are likely embellished to lend prestige to the towns, much like early Christian churches claiming apostolic foundations.

The Exiles and the Lure of Gold

Other chronicles tell of Islamic heretics and outcasts fleeing persecution in the Middle East. The Chronicle of Kilwa recounts the story of Ali bin Hasan, a Persian prince who bought Kilwa Island with cloth and established a new kingdom. These tales, though contradictory, reflect the complex interplay of migration, trade, and cultural exchange that shaped the Swahili coast.

The First Swahili Towns: Settlements and Trade

The Importance of Fresh Water and Strategic Locations

Settlement on small islands or on the seafront is entirely dependent on the ability of its inhabitants to construct wells in order to extract fresh water from the ground. Otherwise, settlements have to be located beside rivers at a point above the high tide mark for fresh water to be available. There is evidence that mainland settlements did exist before those on islands and near beaches. Rhapta, which Ptolemy said was “set back a little from the sea”, is a possible example. Pottery remains dated to the ninth century have been unearthed in the delta of the Tana River, including finds at a settlement called Ungwana, situated on a raised beach beside a tributary of the Tana River. However, the ability of towns lying a short distance inland to carry out international maritime trade is limited and fails to take advantage of such natural geographical features as beaches, deep harbours and estuaries. Seafront settlement, particularly on islands, was therefore a revolutionary step forward.

The Lamu Archipelago: A Cluster of Ancient Towns

Archaeology now suggests that the earliest part of the Swahili coast to be extensively settled was the Lamu Archipelago, a cluster of hot, low-lying, desert islands off the extreme northern coast of Kenya. The sand dunes here no doubt conceal many more secrets, but the work done so far on the three main islands of Lamu, Manda and Pate suggest that at least eight towns existed here more than a thousand years ago.

In 1980, the Cambridge archaeologist, Mark Horton, began the first in a series of six excavations at Shanga, a now-ruined, stone town on the southern shore of Pate Island. It is the oldest site known on the coast and possibly the first to make use of wells. Shanga was probably founded in the middle of the eighth century by Bantu pastoralists who saw trade with the Arabs and Persians as a lucrative, alternative source of income, possibly because of a prolonged drought which had made their previous lifestyle less tenable. Shanga may well have been a temporary settlement at first, inhabited when traders arrived on the north-east monsoon, abandoned when traders returned to the Middle East when the monsoon winds changed direction.

Before Horton’s work in the 1980s, the oldest known settlement was Manda Town, a site on the northern tip of nearby Manda Island. This had been excavated by the then Director of the British Institute of Eastern Africa, Neville Chittick, in 1966, who identified the site as dating from 800AD due to pottery and Chinese porcelain dated to the ninth century. Again, Manda is likely to have been settled on the same temporary basis as Shanga.

The oldest site known outside the Lamu Archipelago, apart from the mainland site of Ungwana, is the town of Unguja Ukuu, the old capital of Zanzibar Island, located seventeen miles south-east of the modern capital. In 1865, a horde of 500 Middle Eastern coins was unearthed there, with one dated as early as 794. In 1965, Neville Chittick uncovered some shards of Islamic pottery and, after comparing his finds with pottery manufactured in the Middle East, Chittick was able to date the pottery, and therefore the site, to the ninth century.

Conclusion: The Legacy of the Swahili Civilization

The Swahili civilization, with its rich history and cultural achievements, stands as a testament to Africa’s vibrant past. From the mysterious ruins of Gede to the bustling trade hubs of the Lamu Archipelago, the Swahili coast was a melting pot of cultures, religions, and ideas. The foundation tales, while not always historically accurate, offer a glimpse into the region’s complex origins and the enduring legacy of its people. As archaeological research continues, the Swahili civilization will undoubtedly reveal even more secrets, further enriching our understanding of this remarkable chapter in human history.