Kenya’s colonial history was shaped by British imperial ambitions, economic exploitation, and African resistance. The British declared Kenya a protectorate in 1895 and later a colony in 1920. Over the next six decades, colonial policies deeply altered the country’s political, social, and economic structures. Land alienation, forced labor, and racial segregation became defining features of colonial rule, triggering significant African resistance movements, culminating in the Mau Mau Uprising and eventual independence in 1963. This article examines the establishment of British rule, its impact on Kenyan society, African resistance, and the road to independence.

The Establishment of British Colonial Rule in Kenya

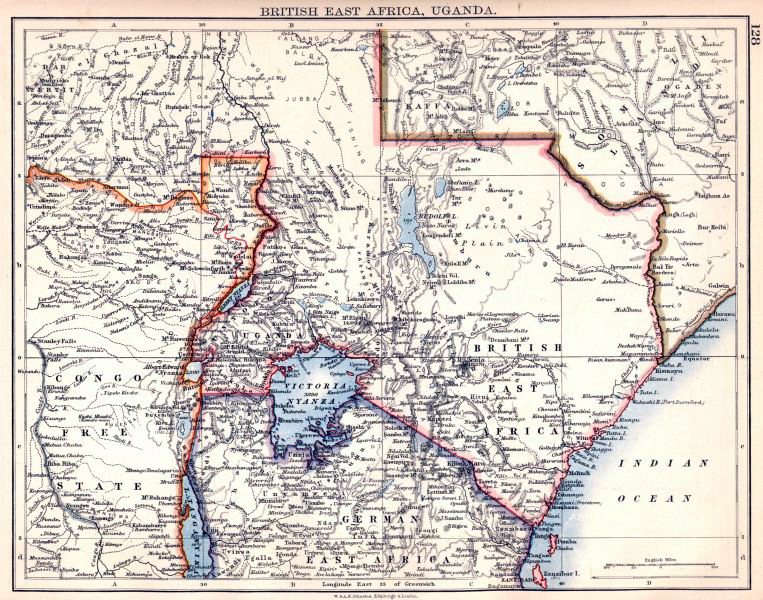

Imperial Expansion and the Uganda Railway (1895-1901)

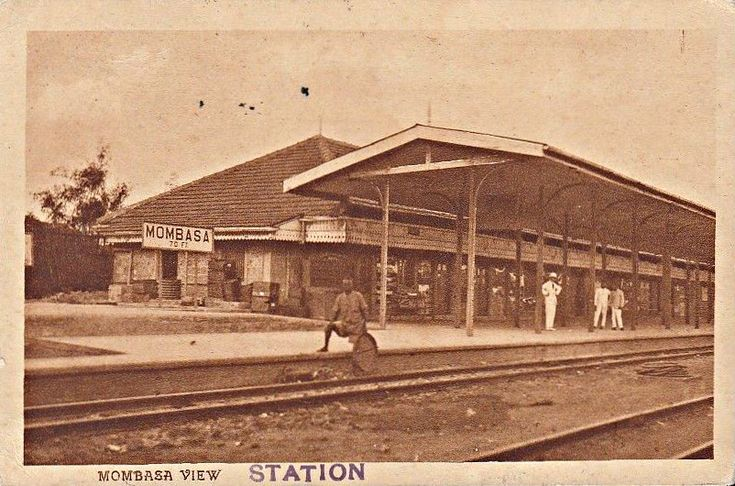

British interest in Kenya was driven by strategic and economic motives, primarily the construction of the Uganda Railway (1896-1901). This railway connected Mombasa to Lake Victoria, facilitating British military control and trade across East Africa (Ogot & Kieran, 1968). The railway’s construction displaced local communities and introduced a significant population of Indian laborers, some of whom later settled in Kenya.

Land Alienation and the White Highlands

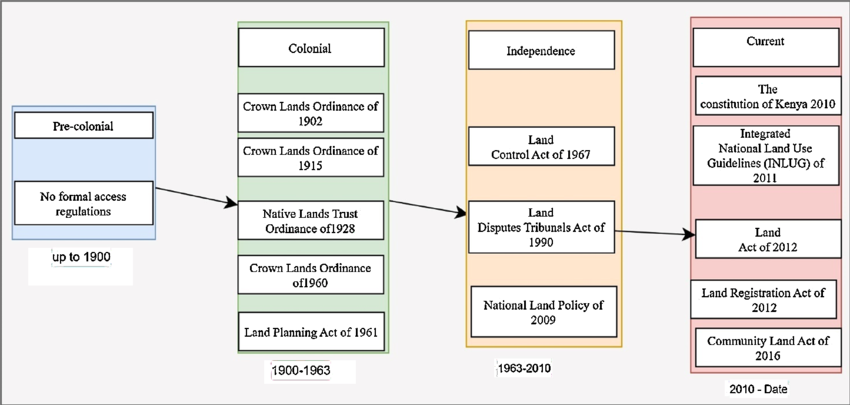

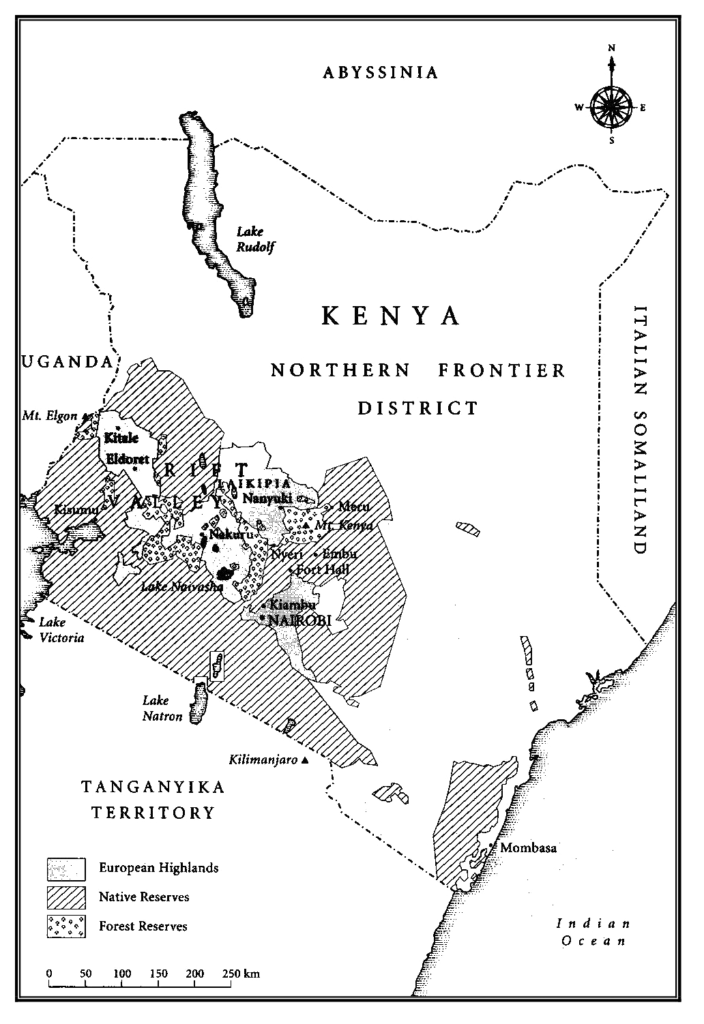

To attract European settlers, the British enacted the Crown Lands Ordinance of 1902, declaring all “unoccupied” land as Crown property. This policy disproportionately affected the Kikuyu, Maasai, and other ethnic groups, displacing them from fertile lands in the White Highlands, which were reserved for European settlers (Throup, 1987). Africans were confined to Native Reserves, limiting their agricultural productivity and increasing dependency on the colonial economy.

Indirect Rule and the Role of African Chiefs

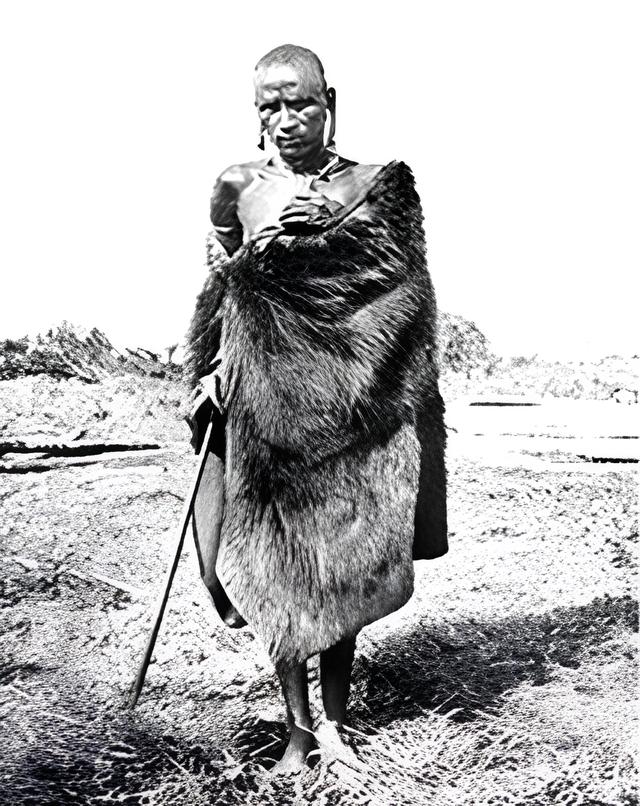

The British implemented indirect rule, governing through local chiefs, many of whom were appointed rather than traditionally chosen. This disrupted indigenous leadership structures and created divisions within African societies. Some chiefs, such as Paramount Chief Koinange wa Mbiyu, benefited from colonial patronage, while others, like Koitalel Arap Samoei of the Nandi, led armed resistance (Berman, 1976).

Economic and Social Impact of Colonialism

Taxation, Forced Labor, and Wage Dependency

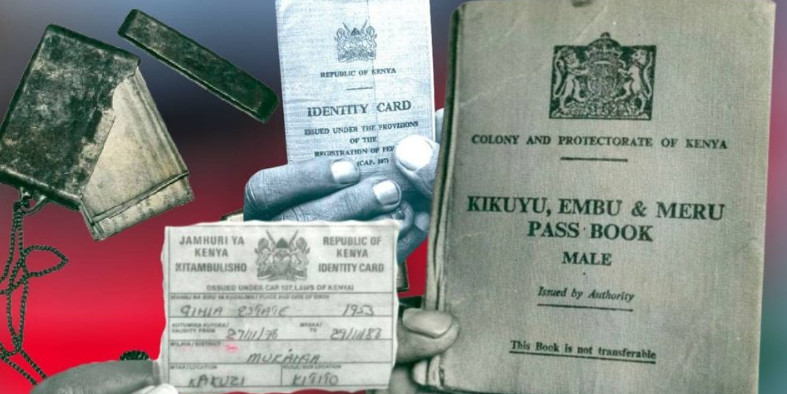

Colonial economic policies were designed to extract resources and labor from Africans for settler farms and British enterprises. The Hut Tax (1901) and Poll Tax (1910) forced Africans into wage labor, as they needed cash to pay these levies. The Kipande System (1919) further restricted African mobility by requiring them to carry identification documents (Presley, 1992).

Racial Segregation and Education Policies

The colonial government institutionalized racial segregation in urban areas, with pass laws limiting African movement. Education was also racially stratified: missionary schools provided minimal education for Africans, focusing on agricultural and vocational training, while European schools prepared settlers’ children for administrative and commercial roles (Nasong’o, Amutabi, & Falola, 2023).

Colonial Agriculture and the Native Land Problem

African farmers faced numerous restrictions under colonial rule. Policies such as the Native Lands Trust Ordinance (1938) limited African land ownership, while the Swynnerton Plan (1954) aimed to increase cash crop production but mainly benefited a small elite (Kanogo, 1987).

African Resistance Against Colonial Rule

Early Resistance (1895-1920)

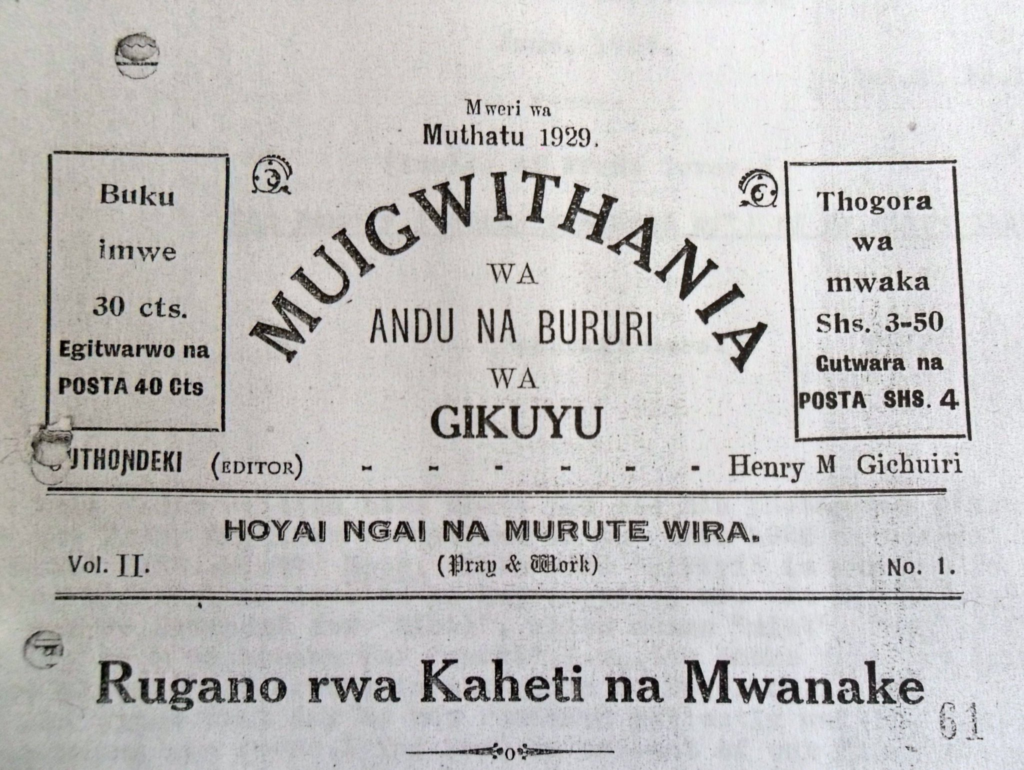

Armed resistance to British rule began immediately. The Nandi Resistance (1895-1906) was led by Koitalel Arap Samoei, whose assassination in 1905 ended the revolt. The Giriama Rebellion (1914-1915) and Kikuyu Female Circumcision Controversy (1929-1930) also reflected African opposition to colonial policies (Leakey, 1952).

Political Mobilization (1920s-1940s)

As military resistance was crushed, Africans turned to political activism. The Kikuyu Central Association (KCA), founded in 1924, became a leading force advocating for land rights and political representation. Figures like Jomo Kenyatta and Harry Thuku gained prominence, with Thuku’s arrest in 1922 sparking protests (Throup, 1985).

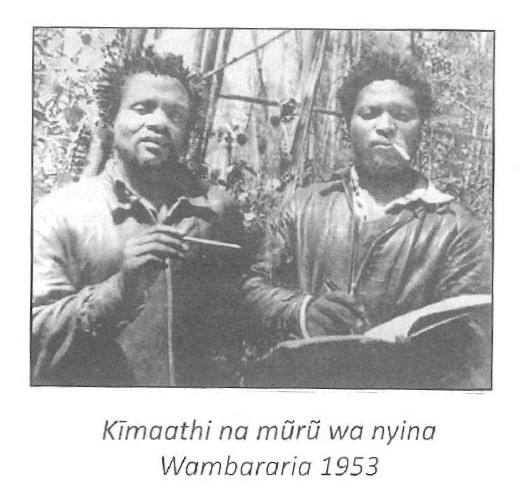

The Mau Mau Uprising (1952-1960)

The most significant anti-colonial movement was the Mau Mau Uprising, primarily led by the Kikuyu, Embu, and Meru communities. Frustration over land alienation and political exclusion fueled this guerrilla war. The British response was brutal, including mass detentions, the villagization of over 1 million Kikuyu, and the execution of Mau Mau leaders like Dedan Kimathi in 1956 (Berman, 1976). Despite British claims of victory, the rebellion accelerated Kenya’s path to independence.

The Road to Independence

The Lancaster House Conferences (1960-1962)

Following the Mau Mau Uprising, Britain initiated constitutional negotiations. The Lancaster House Conferences resulted in the first African-majority government, paving the way for independence (Nasong’o et al., 2023).

Independence and Post-Colonial Challenges

On December 12, 1963, Kenya gained independence with Jomo Kenyatta as its first Prime Minister. However, post-independence Kenya faced challenges, including land redistribution, ethnic tensions, and economic disparities inherited from colonial rule (Ogot & Kieran, 1968).

Conclusion

Colonialism in Kenya reshaped the country’s political, social, and economic landscape. British policies facilitated land dispossession, racial segregation, and forced labor, leading to widespread African resistance. The Mau Mau Uprising marked a turning point, forcing Britain to grant Kenya independence. Today, Kenya continues to grapple with colonial legacies, including land inequalities and ethnic divisions. Understanding colonial history is essential for addressing these enduring challenges.

References

- Berman, B. J. (1976). Bureaucracy and Incumbent Violence: Colonial Administration and the Origins of the Mau Mau Emergency in Kenya. British Journal of Political Science, 6(2), 143-175.

- Kanogo, T. (1987). Squatters and the Roots of Mau Mau, 1905-1963. James Currey Publishers.

- Leakey, L. S. B. (1952). Mau Mau and the Kikuyu. Routledge.

- Nasong’o, W. S., Amutabi, M. N., & Falola, T. (2023). The Palgrave Handbook of Kenyan History. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Ogot, B. A., & Kieran, J. A. (1968). Zamani: A Survey of East African History. East African Publishing House.

- Presley, C. A. (1992). Kikuyu Women, the Mau Mau Rebellion, and Social Change in Kenya. Westview Press.

- Throup, D. W. (1985). The Origins of Mau Mau. African Affairs, 84(336), 399-433.