Christianity has played a pivotal role in shaping Kenyan culture since its introduction by European missionaries in the 19th century. While it contributed to advancements in education, health, and governance, it also disrupted indigenous belief systems, cultural practices, and traditional leadership structures. This article explores the historical spread of Christianity in Kenya, its influence on various aspects of society, the challenges it posed to traditional cultures, and its lasting impact on contemporary Kenya.

The Introduction and Spread of Christianity in Kenya

Christianity in Kenya has a much longer history than previously thought. While European missionaries in the mid-19th century played a significant role in its expansion, historical records suggest that Christian communities may have existed on the Kenyan coast centuries earlier.

In 1498, Vasco da Gama’s journal from his first voyage to India reveals that upon arriving in Mombasa, he expected to hear mass with Christians who lived separately from the Moorish population. He further documented that two fair-skinned men, who claimed to be Christians, visited his ship, and his crew believed them to be so (Ames, 2009). This account suggests that Christianity may have reached the Kenyan coast much earlier, possibly through Middle Eastern, Indian, or Ethiopian trade networks, long before European missionaries formally introduced it inland.

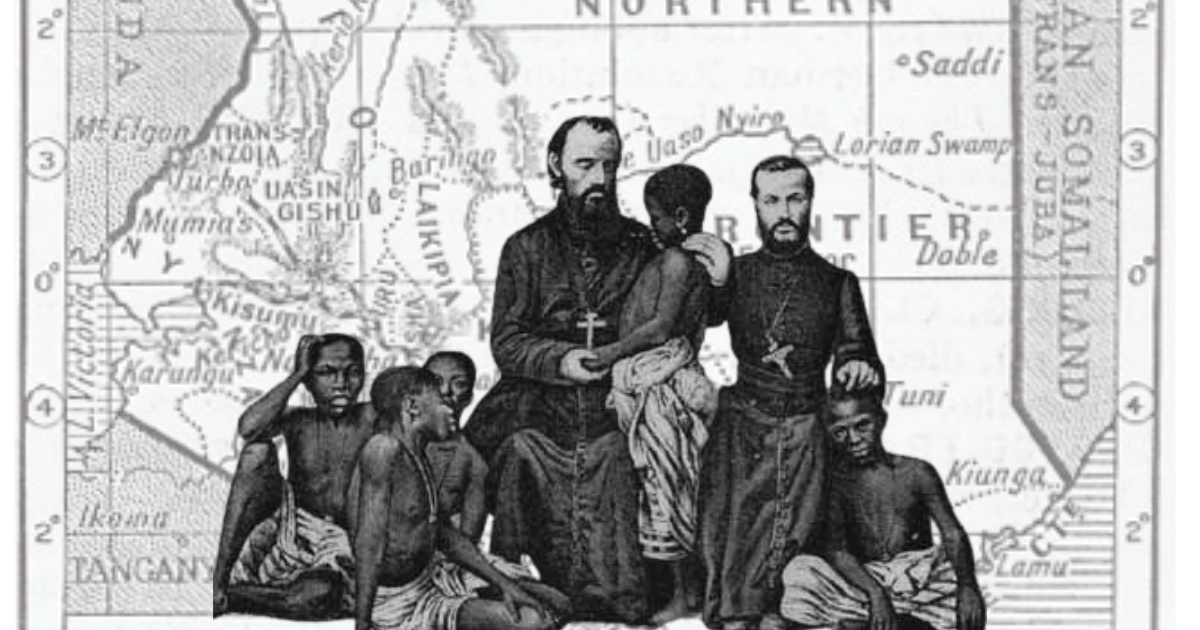

Despite this earlier presence, organized missionary efforts began in the 19th century, when European Christian organizations like the Church Missionary Society (CMS), the Holy Ghost Fathers, the Mill Hill Missionaries, and the Presbyterian Church of East Africa (PCEA) arrived. Early missionaries such as Johann Ludwig Krapf and Johannes Rebmann reached Kenya in the 1840s, setting up mission stations along the coast before expanding inland (Ogot & Kieran, 1968).

The construction of the Uganda Railway (1896-1901) played a critical role in the movement of missionaries into the Kenyan interior. Christian missions gained converts by offering Western education and medical services, particularly in Kikuyu, Luo, and Kamba territories. Institutions such as Alliance High School (1926) and Maseno School (1906) became key centers of African literacy and leadership training, helping shape Kenya’s first Western-educated elite (Nasong’o, Amutabi, & Falola, 2023).

This blend of early coastal Christianity and later missionary expansion reveals a richer and more complex history of Christianity in Kenya than is often recognized. The presence of Christian groups in Mombasa before 1498 suggests a pre-colonial religious exchange, long before the dominance of European influence in the region

The Impact of Christianity on Kenyan Culture

1. Transformation of Indigenous Belief Systems

Before the arrival of Christianity, Kenyan societies practiced African Traditional Religions (ATR), which involved ancestral veneration, spirit worship, and rituals performed by traditional priests (Leakey, 1952). Christian missionaries condemned these practices as paganism, leading to a decline in indigenous religious observances. Over time, many Kenyans abandoned traditional rituals in favor of Christian worship, which emphasized monotheism and salvation through Jesus Christ.

However, some African communities resisted the complete erasure of their spiritual heritage by incorporating elements of traditional religion into Christianity. The rise of African Independent Churches (AICs), such as the Legio Maria Church among the Luo and the African Church of the Holy Spirit, reflected this hybridization of Christian and African beliefs (Ogot, 1970).

2. Education and Literacy

Christian missionaries strategically used formal education as a means of converting Africans to Christianity. Rather than adapting their teaching methods to the African context, they replicated European-style schools and churches, making both formal education and Christianity appear closely linked to European superiority (Kiereini, 2020). This association made conversion to Christianity seem synonymous with being educated, as reflected in the Kikuyu term “muthomi,” which referred to both an educated person and a Christian (Ogot, 1968).

The Fraser Report of 1909 reinforced this link by advocating academic education for Europeans and Asians, while restricting African education to vocational and religious instruction (Nasong’o, Amutabi, & Falola, 2023). Christian education became compulsory, with African customs and traditions deliberately neglected. Africans were barred from learning English until their final year of primary school, limiting their access to higher education and opportunities in administration (Presley, 1992).

Ojijo Oteko and the Maseno School Strike (1908): The First Revolt Against Missionary Education

Resistance to missionary-controlled education first emerged in Nyanza, not Kikuyuland, as is often assumed. In 1908, a major student strike at Maseno School, led by Ojijo Oteko, demonstrated African dissatisfaction with the Eurocentric curriculum. The students refused to participate in manual labor and demanded more reading and writing lessons, an early sign of their desire to influence their education (Kiereini, 2020). By 1909, Bishop Willis reported that some village schools in Nyanza had already begun drifting away from missionary control, signaling the start of the independent schools movement (Ogot, 1968).

The colonial administration supported missionary schools, particularly for the sons of chiefs, to create a loyal African elite that could serve as clerks and low-level administrators under European rule (Nasong’o et al., 2023). This led to a growing demand for literacy in Nyanza, and by 1916, there were 250 village schools run by African teachers. However, many of these schools operated independently due to a lack of direct missionary oversight (Kiereini, 2020).

John Owalo and the First Independent Schools in Nyanza (1910)

The first major break from missionary-controlled education in Kenya occurred in Nyanza when John Owalo, a former student of the Church of Scotland Mission (CMS) school in Thogoto, founded the Nomiya Luo Mission in 1910 (Ogot, 1968). Owalo, who had briefly converted to Christianity, later rejected missionary teachings and started his own religious movement. His followers built independent schools and churches, demanding a secondary school in Nyanza free from missionary influence (Kiereini, 2020).

However, these schools faced major challenges. Poor resources and limited government support made it difficult for them to compete with well-funded missionary schools. By 1958, most of them were absorbed into mainstream education systems (Nasong’o et al., 2023).

The Kikuyu Independent Schools Movement (1929-1952)

While early resistance began in Nyanza, the most organized independent education movement emerged in Kikuyuland in the 1930s, triggered by the female circumcision controversy of 1929 (Leakey, 1952). The Church of Scotland Mission (CSM) banned female circumcision, a significant cultural practice among the Kikuyu, causing a major fallout between the missionaries and the Kikuyu community. In response, the Kikuyu boycotted mission schools and started their own independent schools, which emphasized both modern education and Kikuyu cultural traditions (Presley, 1992).

By 1934, the Kikuyu Independent Schools Association (KISA) was formed to coordinate these schools. However, some members wanted to completely reject European influence, leading to the formation of a rival group, the Kikuyu Karinga Education Association (KKEA). By 1939, there were 63 Kikuyu independent schools, educating over 12,964 pupils (Kiereini, 2020). These schools became crucial centers of anti-colonial mobilization, fostering nationalist sentiments among young Africans (Nasong’o et al., 2023).

The Githunguri Teachers College and Jomo Kenyatta’s Role

Faced with an increasing demand for trained teachers, KISA and KKEA established a teacher training college at Githunguri, which soon became a center for primary, secondary, and higher education (Presley, 1992). By 1947, its enrollment had surpassed 1,000 students, and Jomo Kenyatta—who later became Kenya’s first president—was appointed principal. This college played a vital role in producing leaders of the independence movement, including leaders of the Mau Mau Rebellion (Leakey, 1952).

Colonial Suppression and the Closure of Independent Schools (1952-1958)

The colonial government viewed independent schools as breeding grounds for anti-colonial activism. When the Mau Mau Uprising broke out in 1952, the government accused independent schools of supporting the rebellion and declared them illegal (Nasong’o et al., 2023). Over 400 schools were shut down, and many were either absorbed into government control or handed over to mainstream missionary churches (Kiereini, 2020).

Despite this repression, independent schools played a crucial role in Kenya’s fight for self-rule. They demonstrated the ability of Africans to organize and sustain their own institutions, laying the foundation for the post-independence education system (Ogot, 1968).

3. Changes in Traditional Governance and Social Structures

Christianity undermined traditional governance systems, which were often rooted in age-set structures and spiritual leadership. Before colonial rule, communities such as the Kikuyu, Maasai, and Luhya were governed by councils of elders, with religious leaders playing a central role in dispute resolution and governance (Berman, 1976). Missionaries encouraged individualism and hierarchical church leadership, which conflicted with communal governance structures.

Additionally, Christian teachings promoted monogamy, challenging African societies where polygamy was a widespread practice (Kanogo, 1987). This led to social divisions, as Christian converts often faced ostracization from their communities for abandoning traditional marriage customs.

4. Gender Roles and the Status of Women

Christianity played a complex role in shaping gender dynamics in Kenya. On one hand, missionary education provided women with opportunities for literacy and economic independence. Schools for girls, such as Kaimosi Girls and Limuru Girls, empowered women by offering vocational and academic training.

On the other hand, Christian doctrine reinforced patriarchal structures by emphasizing male leadership in both the church and the household. Women were often excluded from leadership positions within mission churches, and their roles remained largely domestic (Presley, 1992).

The most contentious issue regarding gender and Christianity in Kenya was the ban on female circumcision (FGM). The Kikuyu Female Circumcision Controversy (1929-1930) erupted when Christian missions denounced the practice, leading to the formation of the Independent Schools Movement, which sought to preserve Kikuyu cultural identity while rejecting missionary control over education (Leakey, 1952).

5. Economic and Agricultural Changes

Missionaries introduced new agricultural techniques, including cash crop farming, which reshaped Kenya’s economic landscape. Coffee, tea, and maize cultivation became prominent, replacing subsistence farming in many regions. Christian missions also introduced wage labor, particularly on settler farms, which contributed to the monetization of the economy (Throup, 1987).

However, mission land policies often favored European settlers, limiting African access to fertile lands. This economic disparity fueled anti-colonial sentiments, with many African converts later joining nationalist movements advocating for land reforms (Nasong’o et al., 2023).

Christianity’s Role in Kenya’s Independence Movement

Christianity’s Role in Kenya’s Independence Movement

By the early 20th century, African Christian converts began challenging missionary paternalism and advocating for self-governance. While missionary education provided literacy and leadership skills, it also promoted European cultural superiority and discouraged African traditions. However, as educated African elites became more politically aware, they used their missionary-acquired education to push back against colonial rule.

The East African Revival Movement and Early Christian Nationalism

The East African Revival Movement (1930s-1950s) was a major catalyst for mobilizing Africans against colonial injustices. Originating from Rwanda and Uganda, this religious awakening soon spread into Kenya and Tanzania, encouraging Africans to question both colonial and missionary authority. While the movement focused on spiritual renewal, it also instilled a sense of collective identity and empowerment, which later influenced political activism (Ogot & Kieran, 1968).

Many nationalist leaders came from Christian-educated backgrounds. Jomo Kenyatta, Kenya’s first president, attended missionary schools, while Elijah Masinde, the founder of Dini ya Msambwa, blended Christian teachings with African religious and anti-colonial sentiments (Nasong’o, Amutabi, & Falola, 2023). Similarly, Harry Thuku, an early anti-colonial activist, was educated in Church Missionary Society (CMS) schools, where he first learned the political significance of literacy and organization.

Christianity, therefore, became a double-edged sword—while missionaries sought to convert Africans into obedient subjects of the British Empire, Africans reinterpreted Christian teachings to challenge colonial oppression. They drew inspiration from biblical narratives of liberation, equating their struggle with the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt (Presley, 1992).

Christianity’s Divided Role During the Mau Mau Uprising (1952-1960)

During the Mau Mau Uprising, Christianity played a contradictory role—some church leaders supported the British colonial authorities, while others sympathized with the nationalist cause.

On one hand, mainstream missionary churches, such as the Anglican Church and the Catholic Church, condemned the Mau Mau rebellion, labeling it terrorism and urging African converts to remain loyal to the colonial government (Throup, 1985). Some Christian converts even joined the Home Guard, the British-backed African militia that fought against the Mau Mau fighters.

On the other hand, several African-led churches and independent Christian movements supported the struggle for land and freedom. Rev. Timothy Njoya, a key figure in Kenya’s later democratic struggles, openly criticized British policies and called for African self-rule. Similarly, members of the African Independent Churches (AICs), such as the African Israel Church Nineveh, embraced anti-colonial resistance, arguing that Christianity should serve the oppressed, not the colonial government (Nasong’o et al., 2023).

The Faith of Dedan Kimathi: Christianity in the Resistance Movement

One of the most complex figures in Kenya’s anti-colonial struggle was Field Marshal Dedan Kimathi, the military leader of the Mau Mau movement. Kimathi’s relationship with Christianity reveals how faith and resistance intertwined.

A recently discovered letter from December 13, 1945, shows that Kimathi was an active member of the church, seeking guidance from village elders and Christian leaders. The letter, written in Kikuyu and later translated into English, was authenticated by the Daily Nation in 1986. In the letter, Kimathi confesses to having sinned by impregnating a young woman and asks for forgiveness from the church elders. He writes:

“I have never left the church, and in case there is a church matter where I can assist, you can always inform me. We need encouragement from you people just as Apostle Paul did to his people.”

This letter indicates that, long before becoming a revolutionary leader, Kimathi sought moral and spiritual direction from the church. Despite later leading an armed rebellion, his early writings suggest he valued Christian teachings and community guidance.

A second letter, written on February 17, 1957, just one day before his execution, further confirms Kimathi’s deep connection to faith. Addressed to Father Marino of the Catholic Mission in Nyeri, Kimathi speaks about his preparation for heaven, expressing gratitude for the spiritual guidance he received from Catholic priests while in prison. He lists Christian books that helped him on his spiritual journey, including:

- Students Catholic Doctrine

- In the Likeness of Christ

- The New Testament

- How to Understand the Mass

- The Virgin Mary of Fatima

Kimathi also pleads for his son’s education, emphasizing the importance of learning within a Christian framework:

“Only a question of getting my son to school… I trust that something must be done to see that he starts earlier under your care.”

This final letter reveals a man who, even in his last moments, found solace in faith. While colonial authorities branded the Mau Mau as anti-Christian, Kimathi’s writings suggest otherwise—he saw no contradiction between faith and resistance. His last request was not for vengeance, but for his child to receive an education in a Christian school.

The Church and the Road to Independence

By the late 1950s, as the British government began to negotiate Kenya’s independence, some church leaders started advocating for African participation in governance. The Catholic Church, which had previously been aligned with colonial authorities, began to support gradual decolonization, recognizing that independence was inevitable (Ogot & Kieran, 1968).

Christian organizations also played a role in educating future leaders. The All Saints Cathedral in Nairobi became a meeting place for Kenyan nationalists, and Christian-based institutions helped train politicians, teachers, and administrators who would later lead post-independence Kenya.

However, even after independence in 1963, tensions remained between African nationalist leaders and missionary churches. While Jomo Kenyatta had benefited from missionary education, his government later distanced itself from mission churches, viewing them as former colonial collaborators. At the same time, African-led churches such as Dini ya Msambwa continued to resist Western religious dominance, calling for a Christianity that was fully African in identity and practice (Presley, 1992).

Conclusion

Christianity has left a lasting impact on Kenyan culture, influencing religion, education, governance, gender roles, and economic structures. While it contributed to literacy and modernization, it also disrupted indigenous traditions and reinforced colonial hierarchies. Today, Kenya remains a predominantly Christian nation, with over 85% of the population identifying as Christian (Nasong’o et al., 2023). However, indigenous spirituality continues to influence many aspects of Kenyan cultural identity, demonstrating the resilience of African traditions despite colonial-era disruptions.

References

Nasong’o, W. S., Amutabi, M. N., & Falola, T. (2023). The Palgrave Handbook of Kenyan History. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kiereini, D. (2020, December 25). Rebellion That Gave Rise to Independent Schools. Business Daily Africa. Retrieved from Business Daily Africa.

Ogot, B. A. (1968). Zamani: A Survey of East African History. East African Publishing House.

Presley, C. A. (1992). Kikuyu Women, the Mau Mau Rebellion, and Social Change in Kenya. Westview Press.

Leakey, L. S. B. (1952). Mau Mau and the Kikuyu. Routledge.