The history of the labour movement in Kenya is deeply connected with the country’s colonial past, economic transformations, and political struggles. As in many African nations under British rule, the emergence of trade unions in Kenya was initially constrained by colonial policies that sought to suppress collective African labour organizing (Mulugeta, 2021). However, through resistance, organization, and eventual political liberalization, Kenya’s labour movement played a crucial role in shaping the nation’s socio-economic and political landscape.

Early Labour Conditions and Colonial Policies

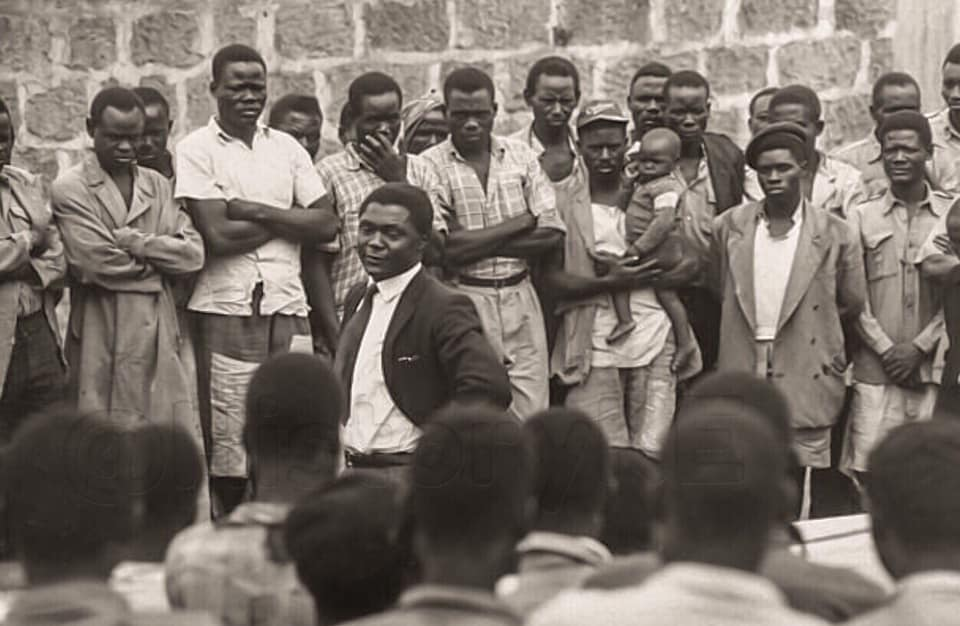

The early 20th century saw the colonial administration in Kenya implementing exploitative labour policies to sustain the settler economy. The introduction of forced labour systems, taxation, and land expropriation compelled Africans to work on European-owned farms, in construction, and in other industries (Mulugeta, 2021). One of the most infamous systems was the Kipande system, introduced in 1921, which required African workers to carry identification documents detailing their employment history. This system restricted their movement and bargaining power, ensuring a cheap and controlled labour force (Mulugeta, 2021).

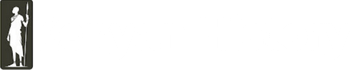

While European and Indian workers had established trade unions early on, African labourers faced significant challenges in organizing. The first recorded strike in Kenya occurred in 1900, but it was not until the 1940s that African workers began forming formal trade unions to demand better wages and working conditions (Durrani, 2009).

The Formation of Trade Unions

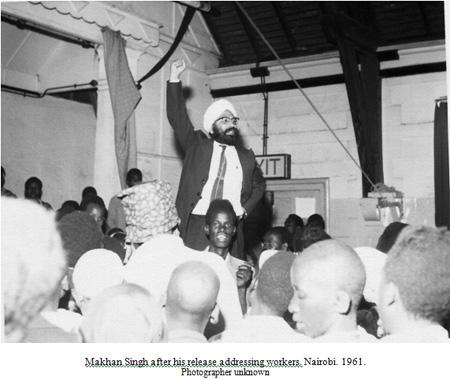

The 1940s and 1950s marked a critical period for Kenya’s labour movement. The country’s economic expansion during and after World War II created a large wage-earning class, particularly in urban areas such as Nairobi and Mombasa (Mohamed, 2021). During this period, pioneers like Makhan Singh and Tom Mboya played instrumental roles in establishing the Kenya African Workers Congress (KAWC) and the Kenya Federation of Labour (KFL) (Mboya, 1957).

The formation of these unions was met with hostility from the colonial administration, which feared that labour activism could fuel anti-colonial resistance. Indeed, the labour movement became closely linked to nationalist movements, and many trade union leaders were also key figures in Kenya’s struggle for independence (Mohamed, 2021).

Labour Movements and the Independence Struggle

By the 1950s, the labour movement had become an essential force in Kenya’s push for self-rule. Strikes and protests organized by trade unions not only sought better working conditions but also challenged the colonial government’s discriminatory policies. The Mau Mau rebellion (1952-1960), though primarily a nationalist and agrarian resistance movement, had significant support from urban workers who were mobilized by trade unions (Throup, 1988).

The State of Emergency declared by the British colonial government in 1952 led to the banning of several trade unions and the arrest of labour leaders such as Makhan Singh. However, this repression did not quell the movement entirely. Instead, it strengthened the resolve of Kenyan workers and their leaders, culminating in the eventual legalization and growth of trade unions as the country approached independence (Ogot, 1968).

Post-Independence Labour Movements

After independence in 1963, the relationship between the government and trade unions evolved. While the labour movement had been instrumental in the struggle for independence, the newly formed government, led by Jomo Kenyatta, sought to exert control over trade unions to maintain political stability. The government-backed Kenya Federation of Labour (KFL) later merged with other unions to form the Central Organisation of Trade Unions (COTU) in 1965 (Mohamed, 2021).

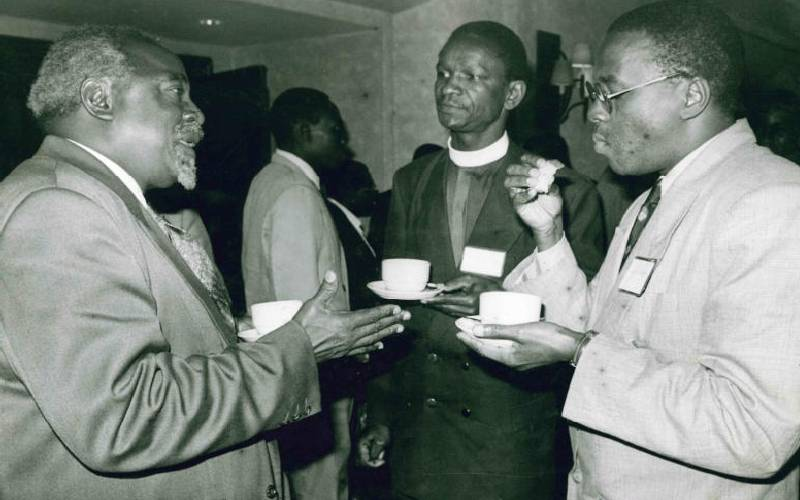

Throughout the 1970s and 1980s, trade unions remained active but were closely monitored and regulated by the state. The government often used coercion to suppress labour activism, particularly under the leadership of Daniel arap Moi (Durrani, 2009). During this period, some trade union leaders collaborated with the government, while others, such as J.D. Akumu and Wilson Makanyaga, continued advocating for workers’ rights under challenging circumstances (Durrani, 2009).

Labour Movements in the Era of Political Liberalization

The 1990s saw significant changes in Kenya’s labour movement, coinciding with the push for multi-party democracy. The liberalization of the political space enabled trade unions to become more vocal in advocating for workers’ rights. Leaders such as Francis Atwoli of COTU played a crucial role in negotiating better wages and working conditions for workers (Mohamed, 2021).

Despite these advancements, challenges persist. The rise of informal employment, lack of unionization among workers in the gig economy, and continued government interference have limited the full realization of labour rights. Additionally, global economic shifts and neoliberal policies have weakened the bargaining power of trade unions (Mohamed, 2021).

Conclusion

The history of the labour movement in Kenya reflects a broader struggle for social justice, economic equity, and political freedom. From its origins in colonial resistance to its role in shaping post-independence governance, the movement has been instrumental in advocating for the rights of Kenyan workers. While significant progress has been made, ongoing challenges require continuous efforts to strengthen trade unions and ensure fair labour practices in Kenya’s evolving economic landscape.

References

Durrani, S. (2009). Trade Union Movement Leads the Way in Kenya. London Metropolitan University.

Mboya, T. (1957). Trade Unionism in Kenya. Kenya Federation of Labour.

Ogot, B. A. (1968). Kenya Under the British, 1895 to 1963. In Zamani: A Survey of East African History.

Throup, D. W. (1988). The Economic and Social Origins of Mau Mau, 1945-1953. Oxford University Press.