Introduction

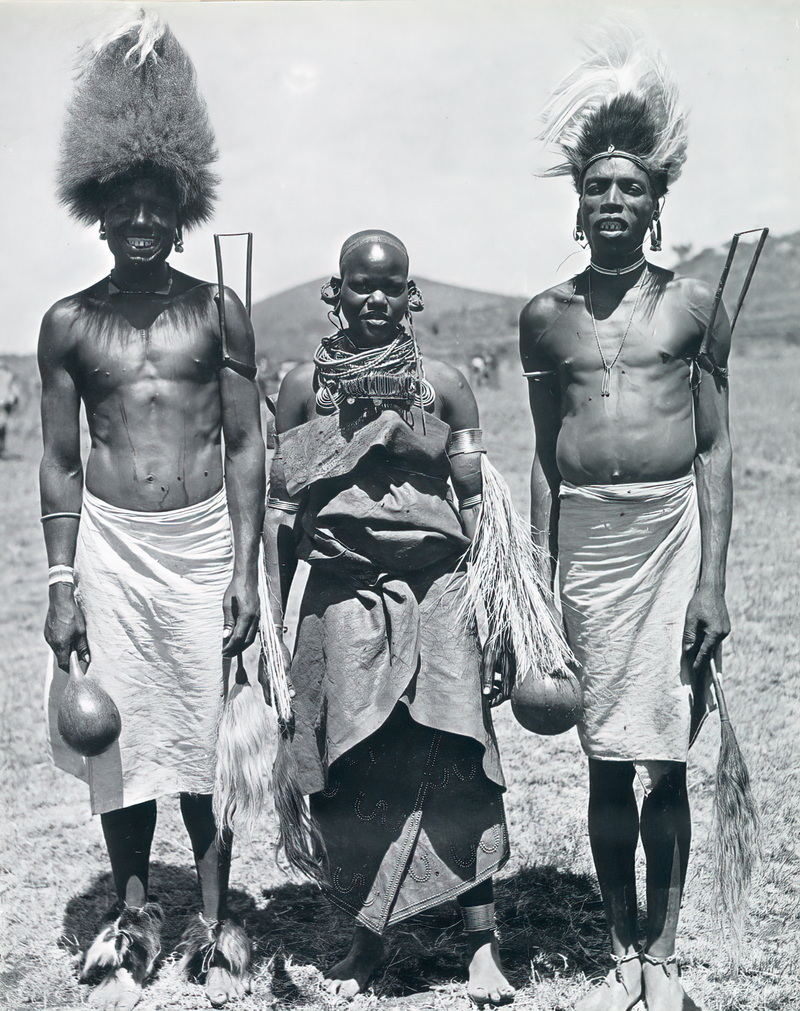

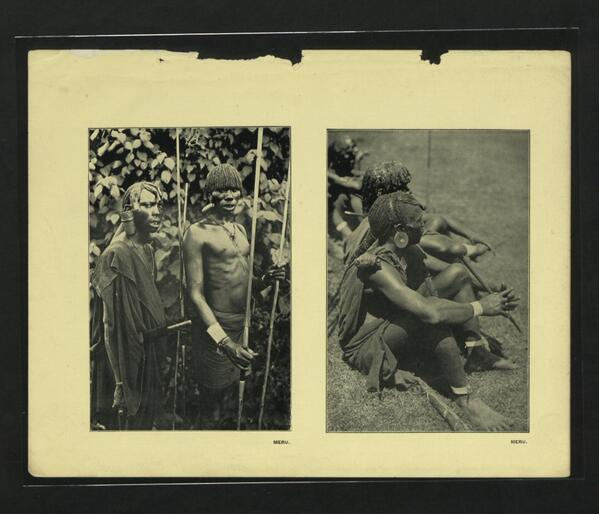

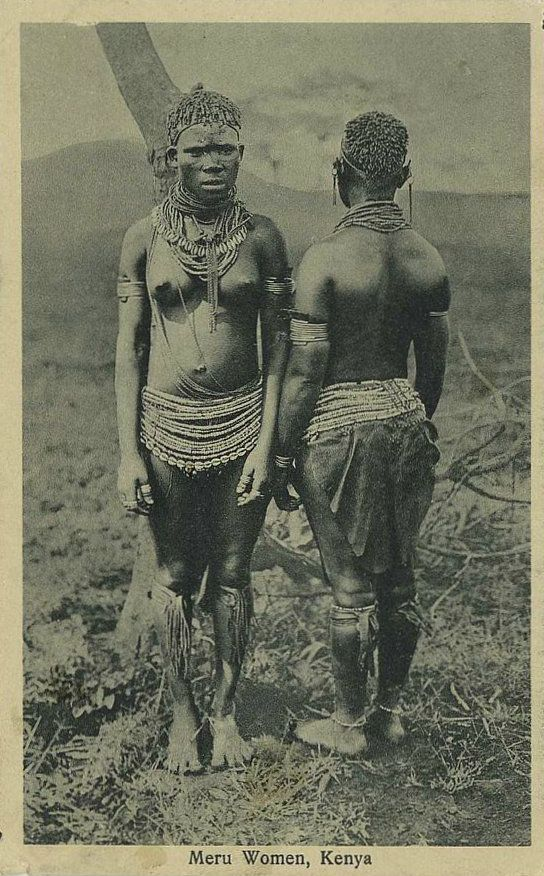

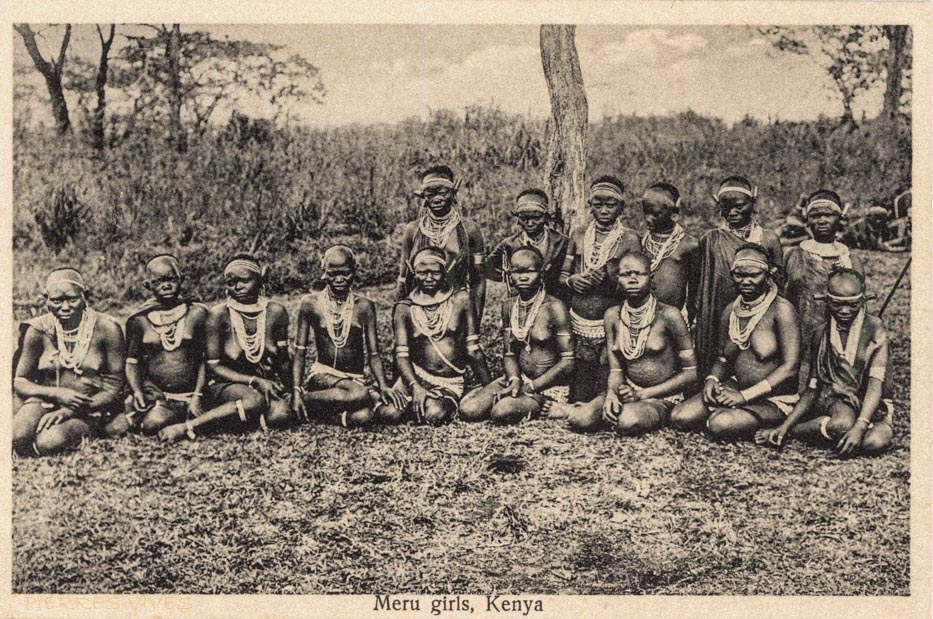

The Meru people of Kenya, who currently inhabit the northeastern slopes of Mount Kenya, have a rich and complex history shaped by migration, oral traditions, and interactions with various groups over centuries. Their origins, debated among scholars, are often traced to multiple ancestral roots, including coastal settlements, Cushitic influences, and connections to ancient African civilizations. The oral history of the Meru, particularly their exodus from enslavement by the Red People (Nguo Ntuni) and subsequent migration, has been compared to biblical narratives, emphasizing themes of oppression, escape, and resettlement. This article provides an in-depth analysis of the historical migration, cultural evolution, and settlement of the Meru people, incorporating oral traditions and scholarly insights.

Geographical and Administrative Aspects of Meru

The Meru region covers approximately 13,000 km² (5,000 sq mi), extending from the Thuci River on the border with Embu County in the south to Isiolo County in the north. Initially, the entire region was referred to as Greater Meru, but after the 1992 administrative reorganization, it was divided into three administrative units: Meru Central, Nyambene, and Tharaka-Nithi (Tharaka and Meru South).

With the 2010 constitutional changes, Greater Meru was further restructured, resulting in the establishment of two counties: Tharaka-Nithi and Meru. The Meru inhabit fertile lands on the eastern and northern slopes of Mount Kenya, making them one of the most agriculturally prosperous communities in Kenya.

The Nine Sections of the Ameru: A Closer Look at Their Distinct Identities

The Meru people are divided into nine major sub-groups, each with its own historical, cultural, and geographical identity. While all these groups share common ancestry, language, and traditions, they developed distinct dialects, settlement patterns, and governance structures over time.

The nine Meru sub-groups are:

- Igoji

- Imenti

- Tigania

- Mitine

- Igembe

- Mwimbi

- Muthambi

- Chuka

- Tharaka

Each of these sub-groups evolved based on geographical, ecological, and historical factors, with some adapting to highland agricultural life while others settled in semi-arid zones, adopting pastoral and mixed farming practices.

1. Igoji

The Igoji people live on the southern slopes of Mount Kenya, bordering the Embu people. They are predominantly farmers, growing bananas, maize, beans, and tea in the fertile highlands. Due to their proximity to the Embu and Kikuyu, they have significant cultural and linguistic similarities with these communities.

Igoji is also known for its deep-rooted Christianity, influenced by early Methodist and Catholic missionary settlements.

2. Imenti

The Imenti people occupy Meru Central, covering areas around Meru Town, the economic hub of the region. They are among the largest and most politically influential sections of the Meru.

Their location along major trade routes led to early interactions with Arab traders, British colonialists, and other Kenyan communities, which helped shape their economic and political prominence.

The Imenti dialect is widely used and has been adopted for written Meru texts, including Bible translations and education materials.

3. Tigania

The Tigania people inhabit the northern Meru region, bordering Isiolo County and the Somali-influenced Borana communities.

Distinct from other Meru sub-groups, the Tigania people have retained some Nilotic cultural traits, possibly due to interactions with the Maasai and Borana during historical migrations.

- Their shields, spears, and traditional ornaments resemble those of the Maasai, indicating a past cultural exchange or intermarriage.

- Unlike highland Meru groups, the Tigania have historically engaged in both agriculture and livestock keeping, taking advantage of the semi-arid lands in their region.

Tigania is also home to Tigania Njuri Ncheke, one of the most powerful councils of elders within the Meru traditional justice system.

4. Mitine

The Mitine people are a relatively smaller group, often closely associated with the Imenti. They live in the central highlands, practicing intensive farming and livestock keeping.

Due to their close proximity to Meru Town and major trading centers, the Mitine people have significantly embraced modernization and education, with many working in urban professions such as business and civil service.

5. Igembe

The Igembe people live north of the Imenti, in areas such as Maua, Laare, and Kangeta. They are best known for their cultivation of miraa (khat), which is a major economic driver in the region.

- Miraa farming has made Igembe one of the most economically significant regions of Meru, with exports to Somalia, Ethiopia, and the Middle East.

- The Igembe dialect has notable differences from the Imenti and Tigania dialects, reflecting their unique settlement history and trade interactions.

The Igembe have historically had strong Njuri Ncheke councils, playing a key role in resolving disputes and maintaining traditional laws.

6. Mwimbi

The Mwimbi people live in the southernmost part of Meru, forming part of Tharaka-Nithi County. They share cultural and linguistic similarities with both the Imenti and Chuka.

Mwimbi is known for:

- Terrace farming, particularly in hilly regions.

- Intermarriage with neighboring Embu and Kikuyu communities.

- Njuri Ncheke leadership, influencing both local governance and regional politics.

Due to their geographical location, the Mwimbi people have historically served as a link between the upper Meru highlands and lower Eastern Kenya.

7. Muthambi

The Muthambi people are closely related to the Mwimbi, and together they form part of Tharaka-Nithi County. They primarily engage in small-scale agriculture, growing bananas, maize, and tea.

Like other Meru sub-groups, the Muthambi have a strong tradition of oral storytelling and folklore, preserving their ancestral history through generations.

8. Chuka

The Chuka people are southern Meru inhabitants who have historically maintained a distinct cultural identity while still sharing language and traditions with other Ameru groups.

Some unique aspects of the Chuka people include:

- A strong warrior tradition, influenced by conflicts with neighboring Maasai groups.

- Preservation of traditional Meru spiritual practices, including divination and nature-based rituals.

- A reputation for craftsmanship, particularly in wood carving, pottery, and beadwork.

Chuka Town is a major commercial center, hosting Chuka University, one of the leading institutions of higher learning in the region.

9. Tharaka: The Semi-Arid Ameru Community

The Tharaka people are unique among the Meru sub-groups due to their semi-arid environment and distinct way of life. They inhabit the lowlands near the Tana River, where conditions are hotter and drier than the fertile highlands of other Meru groups.

Unlike the highland Ameru, the Tharaka are primarily pastoralists and dryland farmers, growing:

- Sorghum and millet, which are drought-resistant.

- Cotton, one of their main cash crops.

- Livestock, including goats and cattle, as an economic backbone.

The Tharaka have historically interacted with:

- The Kamba, adopting some of their trade and cultural practices.

- The Pokomo, exchanging goods along the Tana River trade routes.

Despite living in a more harsh environment, the Tharaka have preserved their Meru heritage, maintaining strong family and community bonds.

Tharaka-Nithi County: A Political and Administrative Shift

Due to historical and geographical factors, the Tharaka, Mwimbi, Muthambi, and Chuka were grouped together to form Tharaka-Nithi County following Kenya’s 2010 constitutional reforms.

- This restructuring helped improve local governance and resource allocation.

- Tharaka-Nithi County has since emerged as a major administrative and economic region, with towns like Chuka and Marimanti becoming important urban centers.

Origins and the Mbwaa Tradition

The predominant oral tradition regarding the early history of the Meru is centered around a place called Mbwaa (Mbwa), which is often described as an island or coastal settlement where the ancestors of the Meru lived under the rule of the Nguo Ntuni (Red People) (Fadiman, 1973). According to Meru oral history, the Nguo Ntuni were oppressive rulers who enslaved the Meru ancestors, forcing them into servitude until they devised a means of escape. Some versions of this oral tradition suggest that Mbwaa was located on Manda Island, off the coast of present-day Kenya, while others place it in Somalia or Yemen (Nyaga, 1997).

This story of enslavement and escape closely resembles the Exodus narrative in the Old Testament, where an oppressed people flee from their captors under divine guidance. Some historians argue that this biblical parallel may have been influenced by contact with Jewish or Ethiopian communities, such as the Falashim of Ethiopia, who had established trade and migration links with the East African coast (Henige, 1982).

Scholarly interpretations of the Mbwaa tradition vary. Some historians believe that the Meru’s reference to “Red People” could have been a term for early Arab traders who controlled parts of the East African coast (Fadiman, 1973). Others suggest that the Meru were part of Bantu-speaking groups that lived along the Kenyan coast before being displaced by external forces, such as the Oromo migrations from Ethiopia or Swahili-Arab coastal expansion.

The Great Migration: The Exodus from Mbwaa

According to Meru oral tradition, their ancestors escaped Mbwaa under the leadership of a prophet named Koomenjwe (Mwithe). The story describes how the Meru crossed a great body of water by supernatural means, an event that some historians believe refers to crossing the flooded Tana River Delta rather than an actual sea crossing (Fadiman, 1973).

Once they reached the mainland, the Meru continued migrating inland, possibly due to hostility from coastal communities or the search for more fertile lands. Historians suggest that this migration took place around 1700-1750, lasting for nearly three decades before they reached Mount Kenya (Henige, 1982).

The migration route likely followed:

- The Tana River Basin, which provided a source of water and sustenance.

- The Eastern Highlands, where they encountered and possibly intermingled with Cushitic-speaking groups.

- The Northern Slopes of Mount Kenya, where they eventually settled.

During this journey, the Meru divided into various sub-groups, forming what are now the Tigania, Igembe, Imenti, Tharaka, Mwimbi, Muthambi, Chuka, and Igoji communities.

Encounter with Other Communities

As they migrated inland, the Meru encountered other ethnic groups, including:

- The Cushitic speakers: These groups, possibly related to the Oromo, had already settled in parts of central Kenya. There are theories that some Cushitic elements were absorbed into the Meru population, influencing their language and culture.

- The Kamba: The Kamba had established settlements in the region and may have traded with or even clashed with the incoming Meru (Fadiman, 1973).

- The Kikuyu and Embu: These neighboring Bantu groups also settled near Mount Kenya, and the Meru shared cultural traits with them.

By the time the Meru reached the northeastern slopes of Mount Kenya, they had adapted to highland agriculture and herding, utilizing the fertile volcanic soils of the region. Their settlement pattern involved occupying ridges and river valleys, which allowed them to practice both farming and livestock keeping.

Social and Political Organization

The Meru developed a complex age-set system (ntora), which regulated leadership, military service, and social responsibilities. Unlike centralized kingdoms, the Meru practiced a decentralized governance structure, with councils of elders (Njuri Ncheke) making major decisions. The Njuri Ncheke became the highest judicial and legislative authority, ensuring justice, land allocation, and community governance.

This age-based system played a crucial role in military organization, particularly in defending against external threats such as the Maasai incursions and conflicts with neighboring communities.

Colonial Era and Resistance

When the British colonialists arrived in the late 19th century, they encountered strong resistance from the Meru. The community opposed forced taxation, labor policies, and land alienation. Notably, the Mau Mau rebellion (1952-1960), which sought to reclaim land from British settlers, had significant participation from Meru fighters, who provided warriors and logistical support (Fadiman, 1973).

The British also attempted to undermine the Njuri Ncheke, replacing traditional governance structures with colonial administrators. However, despite these challenges, the Meru retained much of their cultural heritage and governance systems.

Post-Colonial Era and Modern Developments

After Kenya’s independence in 1963, the Meru people integrated into the national political and economic system. Meru leaders played key roles in government, with figures like Jackson Angaine becoming a notable nationalist leader.

Economically, the region has developed agriculture, focusing on cash crops like tea, coffee, and miraa (khat), as well as dairy farming. Urbanization has also transformed Meru County, with Meru town emerging as a key economic hub.

Religion and Christianity’s Influence

Traditionally, the Meru believed in Murungu, a supreme God, and practiced ancestral worship. Over time, the Methodist Church became dominant in Meru following Christian missionary work, which led to:

- The decline of traditional spiritual practices.

- The reduction of influence of spiritual leaders (Mugwe).

- The establishment of mission schools, hospitals, and churches.

Despite widespread Christianity, some Meru people still observe traditional rituals, especially among the older generations and those in rural areas.

7. Economic and Agricultural Contributions

The Meru are predominantly agrarian, growing staple crops like maize, sorghum, millet, and beans alongside cash crops such as coffee, tea, bananas, and miraa (khat). Notably, the Meru were among the first indigenous Africans in Kenya to grow coffee in the 1930s, following policy changes that allowed African participation in the cash crop economy.

Meru County is also a major commercial hub, with its economy driven by:

- Dairy farming and livestock keeping.

- Tourism, with attractions like Meru National Park.

- Iron ore mining in Tharaka and other mineral explorations.

8. The Role of Meru in Kenya’s Politics

Politically, the Meru have historically aligned with their Bantu neighbors, particularly the Kikuyu and Embu, through the Gikuyu-Embu-Meru Association (GEMA), which was influential in post-independence politics.

Following multi-party democracy in the 1990s, the Meru voting patterns have shifted, with some regions aligning with opposition movements, while others remain tied to the traditional central Kenya political alliances.

Conclusion

The history of the Meru people reflects a fascinating blend of migration, adaptation, and cultural resilience. Their oral traditions provide valuable insights into their origins, while archaeological and linguistic studies help place them within broader Bantu migrations. The Meru’s unique governance system, marked by the Njuri Ncheke, has helped preserve their identity through centuries of change. Today, the Meru remain a vibrant and influential community in Kenya, maintaining strong cultural traditions while embracing modernization.

References

- Fadiman, J. A. (1973). Early History of the Meru of Mt. Kenya. The Journal of African History, 14(1), 9-27.

- Henige, D. (1982). Word of Mouth: Oral Historiography. Harlow: Longman.

- Nyaga, D. (1997). Customs and Traditions of the Meru. East African Educational Publishers.