The Kipsigis are one of Kenya’s largest and most influential ethnic groups, known for their rich cultural heritage, distinct social structures, and deep-rooted traditions. As part of the larger Kalenjin community, they have a long history that traces back to the Upper Nile region before eventually settling in the highlands of western Kenya. Over the centuries, the Kipsigis have preserved their unique customs while adapting to changing social, political, and economic landscapes.

Understanding the history, origin, and customs of the Kipsigis offers a fascinating glimpse into their migration patterns, governance systems, and deeply held beliefs. Their society, traditionally organized around age sets, cattle wealth, and clan-based leadership, has maintained a strong sense of unity despite external influences such as colonial rule and modern development. Rituals such as initiations, marriage ceremonies, and spiritual practices reflect a deep connection to their ancestry and environment.

However, like many indigenous groups, the Kipsigis have had to navigate the challenges brought by European colonization, land dispossession, and integration into a modern nation-state. Their transition from a predominantly pastoralist lifestyle to agricultural and commercial engagements has reshaped their way of life while retaining their identity’s core aspects.

This article delves into the origins of the Kipsigis, their migration history, traditional customs, and the impact of colonialism on their society. By exploring their past and present, we gain a deeper appreciation for the resilience and cultural richness of this remarkable community.

II. Origins and Migration of the Kipsigis

The Kipsigis people trace their origins to the Upper Nile region, an area encompassing parts of present-day South Sudan and Ethiopia. Linguistic and historical evidence suggests that they are part of the larger Nilotic migration, which saw various groups move southward in search of arable land, pasture for livestock, and favorable climatic conditions (Bangura, 1994).

A. Migration and Settlement

According to oral tradition, the Kipsigis migrated from the Upper Nile, traveling through Sudan and northern Uganda before settling in western Kenya. Their movement was influenced by both environmental factors and interactions with other ethnic groups. Some sources suggest that early Kipsigis groups settled near Mount Elgon before moving further south to the Kericho region (Orchardson, 1935).

A well-known origin myth tells of a group of Kipsigis travelers who, upon arriving at their current homeland, encountered an old woman weaving a basket called kisgisik. This name eventually became associated with the group, symbolizing their settlement in the area (Bangura, 1994). Another version suggests that the name is linked to early weaving traditions that were central to their community.

By the 18th century, the Kipsigis had firmly established themselves in the highlands of western Kenya. However, their settlement was not without conflict. They encountered resistance from the Gusii people, leading to a series of territorial battles. The most significant of these was the Battle of Chemoiben in the mid-18th century, where the Kipsigis emerged victorious, securing their dominance in the region. Later, they clashed with the Maasai, leading to prolonged territorial disputes that ultimately defined their boundaries. The Amala River became a natural border between Kipsigis and Maasai territories (Bangura, 1994).

B. Population Growth and Expansion

The population of the Kipsigis has grown significantly over time. In 1939, they numbered approximately 80,000, and by the early 1980s, their population had surpassed 500,000 (Bangura, 1994). Today, the Kipsigis are one of Kenya’s most populous ethnic groups, with a strong presence in Kericho, Bomet, and parts of Nandi and Narok counties.

C. Cultural Influence of Migration

As the Kipsigis migrated and settled, they absorbed and adapted elements from neighboring communities. They share linguistic and cultural similarities with the Nandi, another Kalenjin-speaking group, and have historically interacted with the Maasai in trade and warfare (Orchardson, 1935). These interactions have influenced their social structures, particularly in governance, military organization, and pastoral practices.

Despite changes brought by colonialism and modernization, the migration history of the Kipsigis remains a defining part of their identity. Their oral traditions continue to pass down stories of their journey, territorial conquests, and adaptation, reinforcing their deep connection to their land and heritage.

III. Traditional Kipsigis Society and Organization

The Kipsigis society has historically been structured around communal principles, with a strong emphasis on age-based roles, kinship ties, and collective decision-making. Unlike centralized kingdoms, the Kipsigis maintained a decentralized governance system where leadership was distributed among elders and councils rather than a single ruler. Their social organization has played a crucial role in maintaining stability, regulating communal responsibilities, and upholding cultural values.

A. Social Structure and Age-Sets (Ipinda)

The Kipsigis people follow a structured social system based on age-sets (ipinda), a practice common among Nilotic-speaking communities. The ipinda system is a generational classification that groups individuals based on their age and assigns them specific societal responsibilities (Bangura, 1994).

Each ipinda progresses through a cycle lasting approximately 105 years. A new ipinda can only be established after it has been determined that all members of the previous set have passed away. Boys transition through three primary life stages within the system:

- Boyhood (Laitiik) – Young boys are responsible for light household tasks, herding cattle, and preparing for adulthood.

- Warriorhood (Murenik) – Young men, following initiation rites, become warriors responsible for protecting the community, conducting cattle raids, and upholding social norms.

- Elderhood (Poiyotik) – Elders take on leadership roles, serving as decision-makers and mediators in community matters (Orchardson, 1935).

Women also follow a similar age-grade system, although their responsibilities are more focused on family life, domestic duties, and participation in cultural ceremonies.

B. Clans and Kinship Organization

Kinship plays a vital role in Kipsigis society, and clans (oret) form the foundation of social organization. Each clan traces its descent through the paternal line and shares a common totemic symbol, which often represents an animal, plant, or natural feature. These totems are considered sacred, and members of a clan are prohibited from harming or consuming their respective totem (Bangura, 1994).

Marriage customs among the Kipsigis emphasize exogamy, meaning individuals must marry outside their own clan to strengthen inter-clan relationships and maintain social harmony. The extended family structure ensures mutual support, with multiple generations living within close proximity and contributing to shared responsibilities (Orchardson, 1935).

C. Governance and Conflict Resolution

Traditional governance among the Kipsigis is decentralized, with decision-making primarily occurring at the village level (kokwet). The kokwet serves as the fundamental administrative unit, where elders gather to discuss community matters, mediate disputes, and enforce social norms (Bangura, 1994).

The village council is composed of respected male elders known as kokwetab poiyot, who settle conflicts through consensus. Unlike centralized chiefdoms or monarchies, the Kipsigis emphasize egalitarianism, where leadership is based on wisdom and experience rather than inherited status. Disputes between different villages or ethnic groups were historically resolved either through negotiation or, in extreme cases, through warfare (Orchardson, 1935).

During the pre-colonial period, Kipsigis military organization was structured into different army units (poriosiek), each associated with a specific region. Initially, the military was divided into four units, reflecting the sacred nature of the number four in Kipsigis cosmology. However, after suffering defeats from external groups, the Kipsigis restructured their army into a single cohesive force, improving their defensive capabilities (Bangura, 1994).

D. Religious Beliefs and Spiritual Practices

The Kipsigis have traditionally practiced a form of indigenous spirituality centered around a supreme deity, Asis, who is often associated with the sun. However, Asis is not considered the sun itself but rather the creator and sustainer of life. In addition to Asis, the Kipsigis believe in ancestral spirits who serve as intermediaries between the living and the divine (Bangura, 1994).

Religious practices involve various rituals, sacrifices, and communal ceremonies. One of the most significant ceremonies is Kapkoros, an annual gathering where a high priest (Boyot ab Tumda) leads prayers and blessings for the community. The ritual involves sprinkling participants with a mixture of milk and iron oxide while reciting prayers for prosperity, fertility, and protection from misfortune (Orchardson, 1935).

Magic and supernatural beliefs also play an important role in Kipsigis spirituality. Traditional healers, known as chebsogeyot, use herbal medicine, charms, and spiritual interventions to treat illnesses and ward off misfortune. However, some forms of supernatural power, such as witchcraft (ponisyet), are feared and condemned by the community (Orchardson, 1935).

E. Economic Life and Livelihoods

Traditionally, the Kipsigis economy revolved around livestock keeping, with cattle serving as a primary source of wealth and status. Owning large herds signified prosperity, and cattle played a crucial role in various social transactions, including bridewealth payments during marriage negotiations (Bangura, 1994).

In addition to pastoralism, the Kipsigis also engaged in subsistence farming, growing crops such as millet, sorghum, and later maize, which was introduced during the colonial era. With the advent of British colonial rule, Kipsigis land was increasingly converted into commercial agricultural zones, particularly for tea plantations. This shift significantly impacted traditional economic practices, leading many Kipsigis to adopt a mixed economy that combined livestock rearing with cash crop farming (Orchardson, 1935).

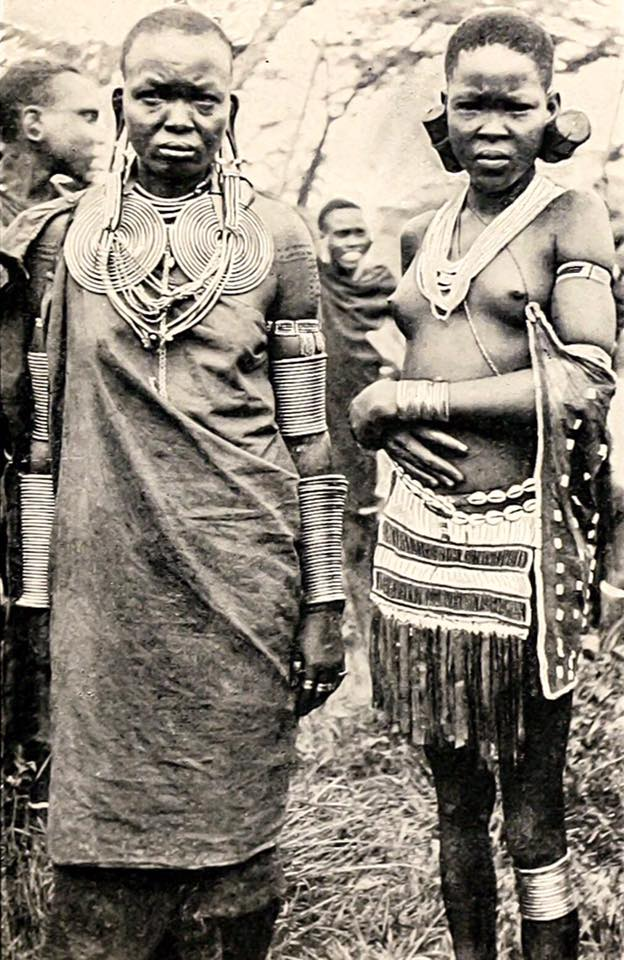

IV. Cultural Practices and Customs

The cultural identity of the Kipsigis is deeply rooted in their traditions, which encompass rites of passage, marriage customs, religious beliefs, and social interactions. These customs have been passed down through generations, reinforcing communal values and social cohesion. While modernization and external influences have introduced changes, many traditional practices remain central to Kipsigis life.

A. Initiation Rites and Coming-of-Age Ceremonies

One of the most significant traditions among the Kipsigis is the initiation ceremony, which marks the transition from childhood to adulthood. This rite of passage is considered essential for full integration into society. It involves a series of rituals, including circumcision, seclusion, education on cultural values, and symbolic reintegration into the community (Bangura, 1994).

1. Circumcision and Seclusion

Circumcision is a central aspect of Kipsigis initiation, performed on both boys and girls as a test of endurance and a demonstration of bravery. Historically, boys underwent the procedure at ages 14 to 18, while girls were initiated at an earlier age. However, female circumcision has been largely discouraged in recent years due to human rights concerns (Orchardson, 1935).

After circumcision, initiates are secluded for several months, during which they receive instruction on Kipsigis customs, responsibilities, and social conduct. Boys are taught about leadership, warfare, and herding, while girls learn about homemaking, motherhood, and societal expectations (Bangura, 1994).

2. Ritual Cleansing and Reintegration

The final phase of initiation involves a series of purification rituals. One of the most symbolic acts is the “dipping of the hands,” where initiates cleanse themselves in a sacred basin to signify their readiness to take on adult responsibilities. Following this, they participate in a grand procession where they are publicly recognized as adults (Bangura, 1994).

For boys, this phase also includes a cattle blessing ceremony, where they symbolically claim ownership over livestock—a vital asset in Kipsigis society. For girls, the ceremony often coincides with engagement arrangements, as they are now considered eligible for marriage (Orchardson, 1935).

B. Marriage and Family Life

Marriage in Kipsigis culture is not just a union between two individuals but a bond between families and clans. It is an institution that plays a significant role in social structure, inheritance, and economic stability.

1. Polygamy and Bridewealth

Polygamy is traditionally practiced among the Kipsigis, with a man taking multiple wives if he has sufficient wealth to support them. A man’s first wife holds a special status and is often consulted before he takes additional wives (Bangura, 1994).

The marriage process involves the payment of kerket ab lakwet (bridewealth), which is usually given in the form of cattle, sheep, and goats. This payment serves as a formal acknowledgment of the union and cements relationships between families. In cases where a woman fails to bear children, the bridewealth must be returned to the husband (Orchardson, 1935).

2. Widow Inheritance and Divorce

Widow inheritance, known as kitunji, is a custom where a deceased man’s younger brother or closest male relative marries his widow to ensure the continuity of the family and property. However, the widow must consent to the arrangement, and this practice has become less common in modern times (Bangura, 1994).

Divorce is traditionally rare and only granted under extreme circumstances such as infertility, adultery, or irreconcilable differences. A childless marriage is one of the few conditions under which a couple may formally separate (Orchardson, 1935).

C. Religious Beliefs and Spirituality

Kipsigis religious beliefs revolve around a supreme deity, Asis, and a strong connection to ancestral spirits. Their spiritual practices reflect a deep reverence for nature, life cycles, and supernatural forces.

1. The Supreme Deity and Ancestral Worship

The Kipsigis believe in Asis, a god associated with the sun and creation. However, they do not worship the sun itself but regard Asis as a life-giver and protector. The god is often invoked in prayers for rain, fertility, and prosperity (Bangura, 1994).

In addition to Asis, ancestral spirits are highly respected. It is believed that the spirits of deceased relatives continue to influence the living, offering protection or punishment depending on the conduct of their descendants. Ancestral veneration is observed through offerings and naming children after deceased family members to honor their legacy (Orchardson, 1935).

2. Role of Priests and Diviners

Religious leadership within the Kipsigis is held by priests (Boyot ab Tumda), who conduct ceremonies, offer blessings, and oversee major communal rituals. They also perform Kapkoros, an annual ceremony where the community gathers to pray for good fortune and protection (Bangura, 1994).

Diviners (chebsogeyot) and traditional healers use herbal medicine and spiritual guidance to cure illnesses and ward off misfortune. Their practices are both respected and feared, particularly in cases involving supernatural forces such as curses or witchcraft (ponisyet) (Orchardson, 1935).

D. Music, Dance, and Oral Traditions

Music, dance, and storytelling play an essential role in Kipsigis culture, serving as a means of preserving history, celebrating life events, and strengthening community bonds.

1. Traditional Songs and Instruments

Music is an integral part of Kipsigis life, with songs performed during ceremonies, work activities, and leisure. The ketuba (stringed instrument) and naururet (flute) are commonly used in performances. Songs often praise heroes, recount myths, or convey moral teachings (Bangura, 1994).

2. Oral Literature and Proverbs

The Kipsigis have a rich tradition of oral storytelling, with folktales and proverbs used to pass down knowledge and cultural wisdom. For example, the proverb “Menemugei chi met” (One cannot shave one’s own hair) teaches the importance of mutual assistance in society (Orchardson, 1935).

E. Beer and Social Gatherings

Beer (mursik), a fermented milk and grain beverage, holds cultural significance in Kipsigis society. It is central to ceremonies, dispute resolution, and social events. Community members share beer in large gatherings, using long drinking tubes to symbolize unity and equality. These gatherings provide a space for discussing village affairs, forging alliances, and reinforcing cultural values (Bangura, 1994).

Women play a key role in brewing beer, and its distribution is governed by specific etiquette. For example, stepping over another person’s drinking tube is considered highly disrespectful. While modernization has altered some aspects of this tradition, beer remains an important cultural symbol (Orchardson, 1935).

V. Impact of European Colonialism

The arrival of European colonialists in Kenya had a profound effect on Kipsigis society, altering their traditional way of life, economy, and governance. Before colonial rule, the Kipsigis had an autonomous social structure centered around clan-based leadership and communal land ownership. However, British colonial policies introduced new administrative structures, land dispossession, forced labor, and economic shifts that reshaped Kipsigis society in irreversible ways (Bangura, 1994).

A. Early European Contact and the Arrival of the British

The first significant European interaction with the Kipsigis occurred in the late 19th century when British colonial agents began exploring the highlands of western Kenya. By 1889, British authorities had established the Imperial British East Africa Company, marking the beginning of colonial rule in the region. This period also saw an increase in trade with Arab and Swahili merchants, who introduced foreign goods such as beads, textiles, and metal tools (Orchardson, 1935).

Despite initial resistance, the Kipsigis were gradually drawn into British control. The construction of the Uganda Railway from Mombasa to Lake Victoria played a crucial role in this process, as it enabled the British to expand their influence and enforce colonial policies more effectively (Bangura, 1994).

B. Land Dispossession and the Creation of the “White Highlands”

One of the most significant impacts of colonialism on the Kipsigis was the large-scale seizure of their land. In the early 20th century, the British declared the fertile highlands of western Kenya as part of the “White Highlands,” designating it for European settlers. As a result, vast tracts of Kipsigis ancestral land were confiscated and allocated to British settlers for commercial farming (Bangura, 1994).

The British justified this land appropriation under the pretense of creating a “buffer zone” between the Kipsigis and the neighboring Gusii. However, it was clear that the primary motivation was to facilitate European economic interests. The loss of land disrupted traditional cattle-herding practices, forcing many Kipsigis into labor on European-owned farms and plantations (Orchardson, 1935).

With the introduction of cash crop farming—particularly tea and pyrethrum—the colonial administration encouraged commercial agriculture. Many Kipsigis were forced to abandon their subsistence farming and pastoralist lifestyles to work as laborers on British-owned plantations. This transition significantly altered their economic structure and introduced new social inequalities (Bangura, 1994).

C. Forced Labor and Taxation

To further control indigenous populations and integrate them into the colonial economy, the British imposed heavy taxation on the Kipsigis. The hut tax and poll tax required every household to pay a fee, which could only be settled through wage labor. Since most Kipsigis had lost their land and access to traditional livelihoods, they were compelled to work on European farms, often under harsh conditions (Orchardson, 1935).

Forced labor policies also contributed to the breakdown of traditional family structures. Young Kipsigis men, who would have otherwise participated in age-set initiations, were forced to leave their homes in search of work in urban centers and European settlements. This migration weakened traditional social bonds and disrupted the communal support systems that had previously sustained Kipsigis society (Bangura, 1994).

D. Colonial Administration and Changes in Governance

The British colonial government introduced a new administrative system that undermined traditional Kipsigis leadership structures. Instead of relying on community elders and village councils (kokwet), the British appointed local chiefs (wootab poiyot), who were responsible for enforcing colonial policies. These appointed chiefs were often selected based on their willingness to cooperate with British authorities rather than their traditional legitimacy (Bangura, 1994).

This shift in governance weakened the traditional kokwet system, as elders lost their authority in resolving disputes and making communal decisions. The colonial administration also introduced Western-style courts and legal systems, which often conflicted with indigenous methods of justice and dispute resolution (Orchardson, 1935).

Additionally, the British used indirect rule, a system where Kipsigis leaders were forced to implement colonial laws while receiving minimal autonomy. This strategy allowed the British to maintain control with minimal resistance while exploiting local structures for administrative convenience (Bangura, 1994).

E. Education and Religious Influence

Colonial rule brought significant changes to the Kipsigis through the introduction of formal education and Christianity. Missionary schools were established, and Western education was promoted as a means of “civilizing” indigenous communities. While education provided new opportunities for literacy and professional employment, it also alienated many Kipsigis from their traditional customs and practices (Orchardson, 1935).

Christianity also played a crucial role in transforming Kipsigis religious beliefs. Missionary groups, particularly the Catholic Church and the Africa Inland Mission, actively converted many Kipsigis to Christianity. This resulted in the decline of indigenous spiritual practices, such as ancestor worship and initiation ceremonies. However, some Kipsigis communities managed to integrate Christian beliefs with their traditional customs, leading to a syncretic form of religious practice (Bangura, 1994).

F. Kipsigis Resistance and the Struggle for Independence

Despite the challenges posed by colonialism, the Kipsigis did not passively accept British rule. They actively resisted land dispossession and forced labor through various means, including organized protests, evasion of taxes, and occasional violent confrontations. The most notable form of resistance came in the form of the Kipsigis Central Association, established in 1947 to advocate for the rights of the Kipsigis people (Bangura, 1994).

During Kenya’s struggle for independence, many Kipsigis supported the nationalist movements that sought to end British rule. While the Mau Mau uprising primarily took place among the Kikuyu, the broader independence movement drew support from diverse communities, including the Kipsigis. By the time Kenya gained independence in 1963, the Kipsigis had begun reclaiming some of their land, although many of the economic inequalities created during the colonial period persisted (Orchardson, 1935).

G. Post-Colonial Legacy and Modernization

Following independence, the Kipsigis, like many other Kenyan communities, faced the challenge of rebuilding their economy and reclaiming their cultural identity. While land reforms were implemented, many former colonial lands remained in the hands of elite landowners. Additionally, the shift from a traditional pastoral economy to commercial agriculture continued to shape Kipsigis livelihoods (Bangura, 1994).

Today, the Kipsigis are among the most economically active communities in Kenya, particularly in the tea industry, which remains a major contributor to Kenya’s economy. However, the legacy of colonialism—including land disputes, economic disparities, and the erosion of indigenous governance structures—continues to impact their society (Orchardson, 1935).

VI. Modern Kipsigis Society

The Kipsigis community, a prominent subgroup of the Kalenjin ethnic group in Kenya, has experienced significant transformations in the post-colonial era. Balancing modernization with the preservation of cultural heritage, the Kipsigis have navigated challenges related to land rights, political representation, economic development, and cultural sustainability.

A. Economic Development and Land Rights

1. Tea Industry and Land Reclamation Efforts

The fertile highlands of Kericho and Bomet counties, traditional Kipsigis territories, have been central to Kenya’s tea industry. However, historical land dispossession during the colonial era led to the establishment of large-scale tea plantations owned by multinational corporations. In recent years, the Kipsigis community has actively sought the return of these ancestral lands. In 2023, the Kipsigis Community Clans Organization petitioned the Kenyan Parliament, highlighting historical injustices and advocating for the restitution of lands occupied by tea companies (Kenya National Assembly, 2023). This move underscores the community’s commitment to reclaiming their heritage and achieving economic empowerment.

2. Environmental Conservation Initiatives

The Kipsigis have also demonstrated a strong commitment to environmental conservation. In response to deforestation and environmental degradation, local villagers initiated a reforestation project, planting approximately 90,000 indigenous trees to restore their historic woodlands (Vidal, 2022). This initiative reflects the community’s dedication to sustainable land management and the preservation of their ecological heritage.de.wikipedia.org+2oret.africa+2en.wikipedia.org+2

B. Political Influence and Inter-Community Relations

1. Political Representation

The Kipsigis have been influential in Kenyan politics, often aligning with broader Kalenjin political movements. Their significant population has afforded them substantial representation in both local and national government structures. This political involvement has enabled the community to advocate for policies addressing their unique challenges, including land rights and economic development.

2. Inter-Community Conflicts and Resolutions

Historically, the Kipsigis have experienced conflicts with neighboring communities, primarily over land and resources. Notably, tensions with the Maasai and Abagusii communities have occasionally escalated into violent clashes (Kenya National Assembly, 2023). However, recent efforts have focused on peacebuilding and conflict resolution. In 2020, leaders from the Kipsigis, Abagusii, Luo, and Maasai communities convened to address and resolve ongoing conflicts, resulting in agreements aimed at fostering peaceful coexistence (The Star, 2020).

C. Cultural Preservation Amid Modernization

1. Sustaining Indigenous Practices

Despite the pressures of modernization, the Kipsigis have endeavored to preserve their cultural practices. Traditional ceremonies, such as initiation rites and marriage customs, continue to be integral to community life, albeit with adaptations to contemporary contexts (National Museums of Kenya, n.d.). Efforts to document and promote Kipsigis culture are ongoing, ensuring that younger generations remain connected to their heritage.

2. Challenges of Cultural Erosion

The encroachment of modern lifestyles poses challenges to the preservation of indigenous cultural practices. The loss of traditional knowledge not only threatens cultural identity but also has ecological implications, as indigenous practices often promote environmental sustainability (Earth Journalism Network, 2021). Addressing this issue requires concerted efforts to integrate traditional knowledge systems into contemporary education and community initiatives.

D. Socio-Economic Challenges and Opportunities

1. Youth Unemployment and Urban Migration

The Kipsigis youth face challenges related to unemployment, prompting migration to urban areas in search of better opportunities. This trend has implications for rural development and the transmission of cultural values. Initiatives aimed at creating local employment opportunities and engaging youth in community development are crucial for sustainable growth.

2. Education and Empowerment

Education remains a vital tool for empowerment within the Kipsigis community. Increased access to education has led to greater representation in various professional fields. However, balancing formal education with the preservation of indigenous knowledge presents an ongoing challenge. Integrating cultural education into formal curricula can help bridge this gap and ensure the continuity of Kipsigis heritage.

Conclusion

The Kipsigis community has demonstrated remarkable resilience in adapting to historical and contemporary challenges while preserving its cultural heritage. From their origins in the Upper Nile region and migration into the Kenyan highlands, the Kipsigis have maintained a strong sense of identity through social structures, economic activities, and cultural traditions.

Colonialism significantly disrupted Kipsigis society, leading to land dispossession, economic restructuring, and political marginalization. The effects of colonial policies continue to shape contemporary issues, particularly in land disputes, economic inequalities, and political representation. However, the Kipsigis have actively sought redress, with recent petitions to the Kenyan government and international bodies highlighting the need for historical justice (Kenya National Assembly, 2023).

Despite these challenges, the Kipsigis have made substantial contributions to Kenya’s economy, particularly in the tea industry, where they are involved in both large-scale and smallholder farming. Additionally, urban migration and access to education have enabled many Kipsigis to enter professional fields, enhancing their influence in national affairs. However, issues such as youth unemployment, environmental degradation, and cultural erosion remain pressing concerns that require sustainable solutions (Vidal, 2022).

Cultural preservation remains a central concern in Kipsigis society. While modernization has introduced new ways of life, community elders and institutions continue to promote indigenous knowledge, traditional practices, and intergenerational learning. Integrating Kipsigis history and customs into formal education systems is crucial in ensuring that younger generations remain connected to their heritage (National Museums of Kenya, n.d.).

Moving forward, the Kipsigis community faces a critical juncture. By leveraging political engagement, economic development initiatives, and cultural preservation efforts, they can achieve long-term stability and prosperity. Collaboration with government institutions, non-governmental organizations, and international human rights bodies will be essential in addressing historical injustices and ensuring that the Kipsigis continue to thrive in a rapidly changing world.

Ultimately, the story of the Kipsigis is one of strength, adaptation, and perseverance. While they continue to navigate modern challenges, their deep-rooted cultural values and community-driven resilience remain defining features of their identity in Kenya and beyond.

References

- Bangura, A. K. (1994). Kipsigis. The Rosen Publishing Group.

- Earth Journalism Network. (2021). Losing indigenous cultural practices has dire consequences for ecosystems in Kenya. Retrieved from earthjournalism.net.

- Food Business Africa. (2024, May 16). Kipsigis clan disputes Lipton Tea Estate sale to Browns Investment PLC. Retrieved from foodbusinessafrica.com.

- Georgetown Journal of International Affairs. (2023, February 2). Fabian Salvioli on the UN Redress for Kenyan Land Dispossession under British Colonization. Retrieved from gjia.georgetown.edu.

- Human Rights Watch. (1999). Tribal clashes in the Rift Valley Province. Retrieved from hrw.org.

- Kenya National Assembly. (2023, March). Petition no. 026- Kipsigis historical injustices. Retrieved from parliament.go.ke.

- Kenya National Assembly. (2023, August). Report on the petition by the Kipsigis Community Clans Organization regarding land injustices against the community. Retrieved from parliament.go.ke.

- National Museums of Kenya. (n.d.). The Kipsigis community of Kenya. Retrieved from artsandculture.google.com.

- NTV Kenya. (2024, June 4). Sale of tea estates in South Rift challenged by community. Retrieved from ntvkenya.co.ke.

- Orchardson, I. Q. (1935). Kipsigis. Cambridge University Press on behalf of the International African Institute.

- ResearchGate. (2021). Impact of Development of Tea Plantation Economy from 1927 to 1963 on Social and Economic Status of Nandi East Sub County, Kenya. Retrieved from researchgate.net.

- The Star. (2020, March 12). Kipsigis, Abagusii, Luo, Maasai agree to end conflicts. Retrieved from de.wikipedia.org.

- Vidal, J. (2022, May 9). A story of 90,000 trees: How Kenya’s Kipsigis brought a forest back to life. The Guardian. Retrieved from theguardian.com.