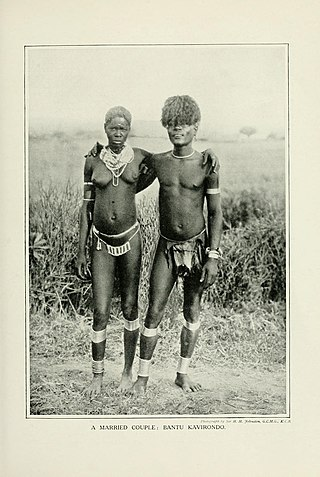

Along the northeastern shores of Lake Victoria in western Kenya lives a diverse group of Bantu-speaking peoples collectively known as the Bantu of Kavirondo. This term, once used by colonial administrators and early anthropologists, refers to several distinct but culturally and linguistically related communities, including the Wanga, Marama, Logoli, Vugusu, and others. Today, most of these groups are part of the broader Luhya identity, one of Kenya’s largest ethnic blocs.

The Bantu Kavirondo have a long and intricate history marked by migration, settlement, adaptation, and resilience. For centuries, they have inhabited the fertile plains and rolling hills of what was once known as the Kavirondo region, a term whose etymology remains uncertain but is deeply rooted in colonial administrative geography. This region was historically shared with their Nilotic neighbours, particularly the Luo (or Jaluo), leading to rich patterns of cultural exchange, conflict, and coexistence.

Understanding who the Bantu Kavirondo are requires not just tracing their physical presence in the region, but also delving into their origin stories, clan structures, belief systems, and the impact of colonial and post-colonial developments on their way of life. Despite the disruptions brought by European imperialism, Christianity, and the modern nation-state, the Bantu Kavirondo have maintained many elements of their traditional identity while also transforming in response to changing times.

This article explores the origins, migrations, and cultural evolution of the Bantu Kavirondo people. It draws on historical, anthropological, and linguistic sources to present a clear, grounded account of how these communities came to be where they are today — and what continues to define them.

Table of Contents

II. Origins and Migrations

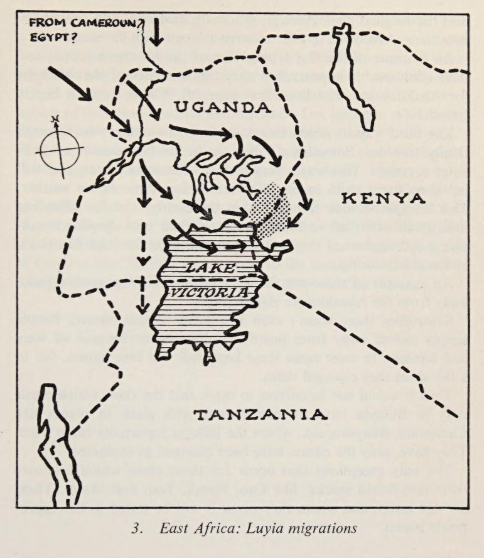

The roots of the Bantu Kavirondo stretch deep into the broader history of the Bantu migrations — a vast and complex movement of people that began thousands of years ago in what is today the border region of Cameroon and Nigeria. Over centuries, waves of Bantu-speaking communities spread across sub-Saharan Africa, bringing with them agriculture, iron-working, and new languages. By around the 14th to 17th centuries, some of these groups had reached the region surrounding Lake Victoria, where they would eventually become known as the Bantu of Kavirondo.

III. Reassessing the Timeline of Bantu Settlement in Western Kenya

For a long time, the commonly accepted estimate for the arrival of Bantu-speaking communities in western Kenya — particularly the group later called the Bantu of Kavirondo — has been drawn from anthropological fieldwork such as that of Günter Wagner in the mid-20th century. Wagner, based on oral testimonies, suggested that most Bantu groups had been in the region for about 10 to 15 generations, roughly equating to 200–450 years by his 1949 publication date. This placed their arrival in the early 17th century (around 1600) or later.

However, newer historical and multidisciplinary evidence challenges and significantly expands this timeframe.

A. Osogo’s Account: “Centuries Before the Luo”

In his book History of the Baluyia, Kenyan historian John Osogo makes a key intervention. He writes that “many Baluyia clans arrived in what came to be known recently as Kavirondo many centuries before the first arrivals of the Luo.” This places Bantu-speaking clans such as the Wanga, Marama, and others in western Kenya well before the 16th century, the period widely accepted for the arrival of the Southern Luo from northern Uganda.

Osogo also clarifies that while some Luhya clans today show signs of Luo influence (e.g. in names or intermarriage), this does not reflect a Luo origin, but rather later boundary interactions and cultural blending.

B. Ogot’s Historical Framework

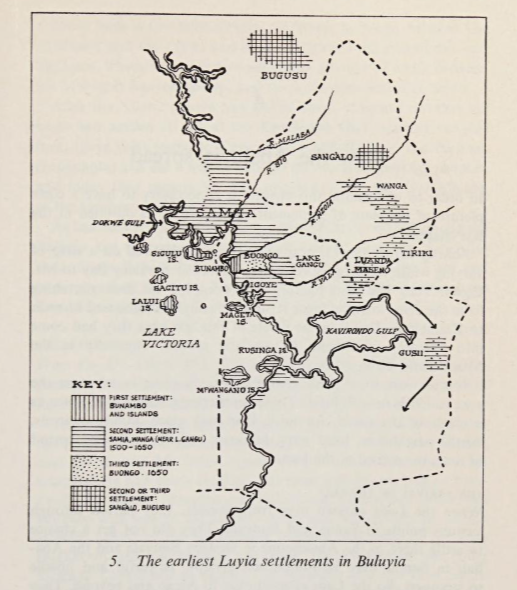

In Zamani and History of the Southern Luo, historian Bethwell A. Ogot provides perhaps the most precise chronology. He divides the arrival of Bantu communities into several waves:

- First wave: Via Lake Victoria islands from Bunyoro and Buganda, as early as the 14th century (1300s CE).

- Second wave: Through Busoga and Bugisu into western Kenya between 1463 and 1625.

- Luo migration: Begins after 1500, with significant settlement in present-day Nyanza between 1520 and 1650.

Ogot also notes that when the Luo entered parts of Alego, Asembo, and Gem, they encountered and often displaced or assimilated Bantu communities already living there — including clans like the Waturi and Kanyibule.

C. The Buganda-Bunyoro Link and Interlacustrine Origins

Drawing on Christopher Wrigley’s work on Buganda, we also learn that many Bantu migrations into Kenya likely originated from the politically advanced Interlacustrine kingdoms such as Buganda and Bunyoro, whose histories stretch back to at least the 14th century. These kingdoms exerted both political and cultural influence over adjacent regions — including parts of Busoga, Samia, and western Kenya — through military conquest and trade networks.

This reinforces the notion that Bantu speakers in western Kenya were part of a much older migration corridor stretching from central Uganda to the shores of Lake Victoria, centuries before the Luo migration began.

D. Reconciling Oral Tradition with Broader Evidence

Oral genealogies, like those used by Wagner, are invaluable but often limited to remembered ancestry — typically around 10–15 generations. However, as Ogot, Osogo, and Wrigley show, when oral histories are cross-examined with:

- Archaeological data (e.g., pottery traditions in Nyanza),

- Linguistic evidence (Luhya dialect dispersal patterns),

- And historical linkages to precolonial Great Lakes kingdoms,

…it becomes clear that Bantu groups were present in western Kenya by the 14th or early 15th century at the latest.

IV. Ethnic Composition and Dialects of the Bantu Kavirondo

The term Bantu Kavirondo, though colonial in origin, refers to the culturally and linguistically diverse Bantu-speaking communities historically inhabiting what is today western Kenya. These include the peoples now commonly grouped under the name Abaluyia or Luhya, a federation of more than twenty sub-groups with distinct identities but shared linguistic and cultural foundations.

These groups occupy territories stretching from the foothills of Mount Elgon to the shores of Lake Victoria. While united by a common language group (Luluhyia), their sub-tribes differ in dialect, clan structure, and historical origins.

A. Sub-Tribes of the Bantu Kavirondo (Abaluyia)

According to John Osogo, the Baluyia (plural of Omuluyia) are organized into 24 sub-tribes, each usually named after a founding ancestor or dominant clan. These include:

- Wanga, Marama, Kabras, Tiriki, Maragoli, Idakho, Isukha, Kisa, Bunyore, Samia, Khayo, Tachoni, Bunyala, Busonga, and others.

Each group has its own oral traditions regarding migration and settlement. For example:

- The Wanga are known for their centralized kingship and close historical ties to Buganda and Bunyoro.

- The Maragoli, Tiriki, and Idakho are more decentralized and maintain strong clan identities.

- The Samia and Khayo are located near the Uganda border and have long histories of cross-border interaction with the Basamia and Bagisu.

B. Dialects and Linguistic Clusters

Each sub-tribe speaks a distinct dialect of Luluhyia, though mutual intelligibility varies:

- Standard Luluhyia is spoken by the Wanga, Marama, Kisa, and Batsotso.

- Dialects such as those of the Maragoli, Tiriki, and Idakho are harder for outsiders to understand and often require slower, careful speech.

- Lunyala and Lusamia, spoken by groups near Uganda, show heavier influence from Luganda and Lusoga.

Osogo explains that these dialects have been shaped by:

- Ecological setting (e.g. highland vs. lake shore),

- Contact with neighbouring peoples (Nandi, Luo, Teso),

- And historical migration routes from Bunyoro, Buganda, and Busoga.

Many dialects have absorbed loan words from neighbouring Nilotic and Cushitic groups, especially among border communities.

C. Dialect and Clan Terminology

Osogo clarifies that the terms tribe, sub-tribe, clan, and sub-clan are used flexibly:

- “Sub-tribe” refers to a major group like Tiriki or Wanga.

- “Clan” refers to lineages within the sub-tribe, often tied to ancestry.

- “Sub-clan” is a further subdivision, often denoting more recent lineage splits.

Also notable is the variety of names used:

- For example, the Abalogoli (Maragoli) may also appear as Avalogoli, depending on dialect spelling.

- The prefix system (e.g., Omuluyia = one Luhya, Abaluyia = plural) reflects typical Bantu noun class structures.

D. Geographic Spread

Osogo provides a map showing the distribution of Luhya sub-tribes across western Kenya, with most communities concentrated in Kakamega, Bungoma, Busia, and Vihiga districts【image p. 14】. Some groups, such as the Bunyala, are also found in Uganda, further showing the cross-border historical continuity of these communities.

V. Social Organization and Kinship among the Bantu Kavirondo

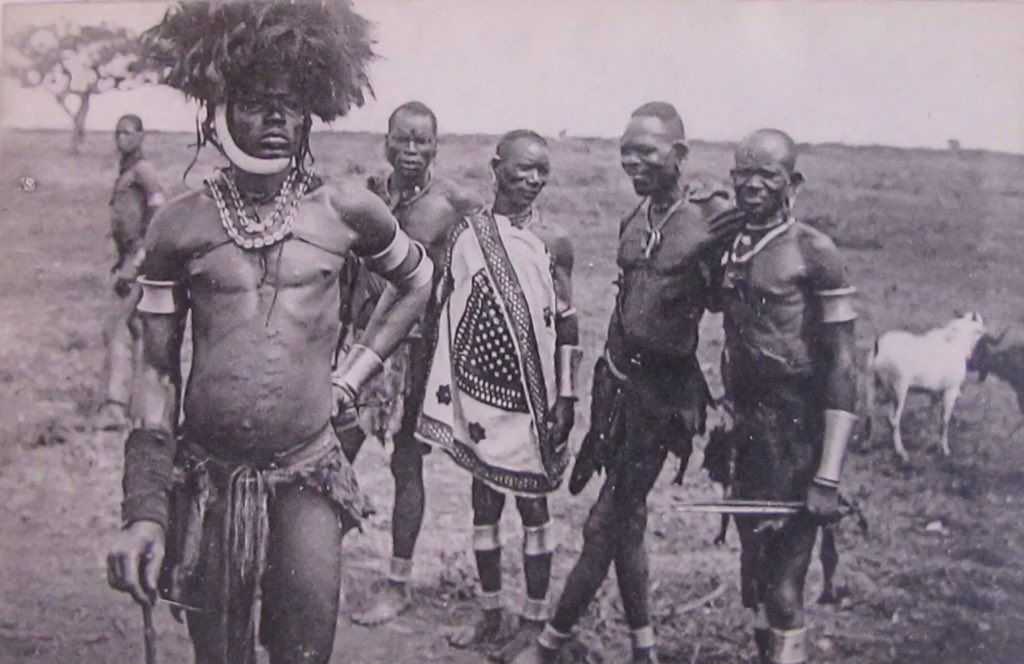

The social organization of the Bantu Kavirondo (Abaluyia) was traditionally based on a clan-based structure grounded in kinship, age sets, and customary law. Each community governed itself through a blend of patrilineal lineage, communal consensus, and ritual authority. These systems shaped not only leadership and family life but also land rights, dispute resolution, and cultural education.

A. Clans and Lineages

Every sub-tribe was composed of multiple clans (ebisutsya) — extended family groups claiming descent from a common male ancestor. These clans often served as the fundamental political, social, and religious units:

- They regulated marriage rules (e.g., one could not marry within their own clan).

- They shared ancestral shrines, land, and totems.

- Clan elders settled disputes and presided over rituals, especially those involving land, birth, and death.

Some clans were indigenous to a region, while others migrated and were absorbed through alliance or conquest. Osogo notes that many clans among the Abaluyia have diverse origins — some tracing their roots to Bunyoro, others to Buganda, and still others to Kalenjin or Nilotic neighbours【image ref. p. 12, Osogo】.

B. Kinship and Inheritance

Kinship among the Bantu Kavirondo was primarily patrilineal:

- Inheritance of land, livestock, and ritual duties passed through the father’s line.

- Boys were raised to belong to their father’s clan, while girls were prepared to marry into other clans, often bringing with them prestige and alliances.

- Elders were respected not just for age but for their ritual knowledge and memory of genealogies.

However, matrilineal ties were not ignored — especially in matters of counsel, marriage negotiations, and conflict mediation. A man’s maternal uncles, for instance, had special ritual obligations during rites of passage.

C. Leadership and Authority

Each sub-tribe had different leadership structures:

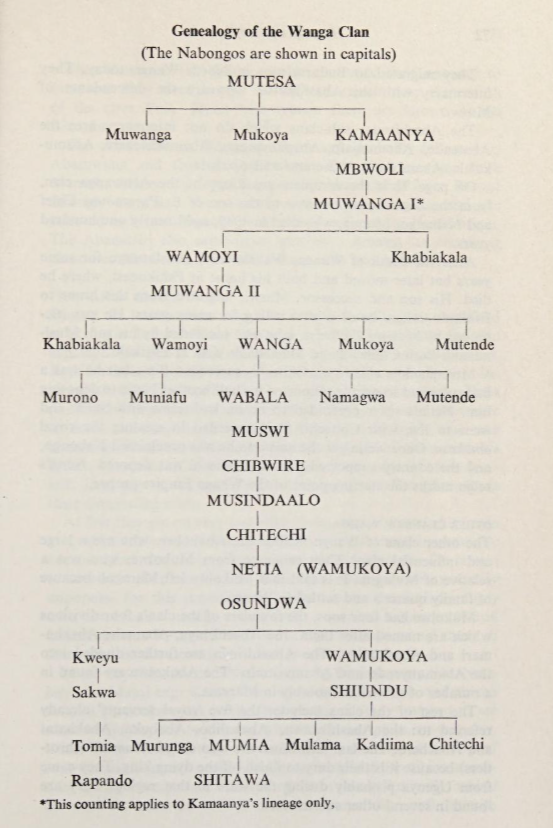

- Wanga: Developed a centralized kingship (Nabongo) based on heredity, taxation, and military authority. This system was influenced by Buganda and Bunyoro, and was unique among the Bantu Kavirondo.

- Other groups (e.g., Tiriki, Maragoli, Kabras): Practiced segmentary lineage organization, where power was diffuse, and elders’ councils (abakulu) made decisions by consensus.

Leadership at the clan level was typically held by a respected elder (omukasa), chosen for his wisdom, fairness, and knowledge of tradition — not necessarily for wealth or force.

In judicial matters, justice was restorative rather than punitive, emphasizing reconciliation, compensation, and the restoration of social harmony. Major decisions required consultation with lineage heads, and wrongs were often settled with livestock fines or ritual cleansing.

D. Age Sets and Social Education

Among groups like the Tiriki and Isukha, boys were inducted into age-sets during initiation ceremonies, which bonded them into lifelong alliances and marked the transition to manhood. Each age-set had duties:

- Younger men handled cattle herding and defense.

- Middle-aged men formed councils of warriors or elders.

- Elder men served as judges, ritual specialists, and political advisors.

Initiation also included teachings on clan history, community laws, respect for elders, and expectations for adulthood. Some sub-groups had elaborate initiation songs, dances, and trials — preserved across generations as oral education tools.

VI. Religion, Belief Systems, and Cosmology of the Bantu Kavirondo

Religion among the Bantu Kavirondo was not a separate institution as it often is in modern societies. It was woven into the fabric of daily life, touching every aspect of existence — from birth and naming to farming, illness, justice, and death. At the heart of their spiritual worldview was a firm belief in ancestral presence, ritual power, and a supreme creator who governed the universe.

A. Supreme Being and Ancestral Spirits

Most Bantu Kavirondo believed in a supreme being, commonly referred to by names such as:

- Wele, Nyasaye, or Were — depending on the dialect or sub-tribe.

- This god was seen as the ultimate creator and sustainer of life but was usually distant and accessed only through ritual intermediaries, such as ancestors or spiritual specialists.

More central in daily religious life were the ancestral spirits (ebikuda or emyoyo):

- The dead were believed to continue living in the spiritual world and could influence the living — positively through blessings or negatively through illness or misfortune.

- Offerings, libations, and special ancestral shrines were used to honor these spirits.

- Ancestors were especially important in land matters, family disputes, and rites of passage.

B. Rainmakers, Diviners, and Healers

Among the Bantu Kavirondo, certain individuals held ritual authority:

- Rainmakers (baluva or babasai) were consulted during times of drought or agricultural distress.

- Diviners (bafumu or avaloji) interpreted dreams, omens, and illness through spirit possession or reading objects like bones, stones, or seeds.

- Herbalists and healers used knowledge passed through lineages to treat ailments — both physical and spiritual.

These spiritual practitioners played critical roles not just in healing, but in maintaining community balance and resolving conflicts. Illness was often seen as a sign of broken social ties, ancestral displeasure, or witchcraft.

C. Rituals and Sacred Spaces

Religious practice involved various communal and household rituals:

- Libations of beer or milk poured on sacred trees, stones, or graves.

- Household shrines, where elders called upon ancestors.

- Sacrifices of goats, chickens, or grain, particularly during initiation, marriage, or planting season.

Specific sites — such as large trees, hills, or rivers — were considered sacred and treated with reverence. Some clans had ritual taboos involving foods, animals, or directions, believed to guard spiritual purity.

D. Belief in Witchcraft and Spirit Possession

Belief in witchcraft (ubulozi or ubufumu) was widespread:

- Misfortune, illness, or crop failure could be blamed on malevolent individuals said to possess harmful spiritual powers.

- Accused witches were sometimes expelled or required to undergo cleansing rituals.

- Protective charms and ritual blessings were used to safeguard individuals, families, or even entire villages.

While feared, these beliefs also formed part of the moral code — reinforcing community values, obedience to elders, and social responsibility.

E. Religious Change Under Colonialism

With the arrival of missionaries in the late 19th century, many Bantu Kavirondo converted to Christianity. However, this shift was gradual and layered:

- Some converted openly but maintained traditional beliefs in private.

- Others blended Christian and indigenous worldviews, creating forms of religious syncretism.

- Mission churches often challenged traditional authority structures, especially those of rainmakers, diviners, and elders.

Even today, many Luhya families continue to honor both Christian teachings and ancestral rituals — a testimony to the resilience of indigenous cosmologies.

VII. Initiation Rites and Life Stages among the Bantu Kavirondo

Initiation rites were central to the cultural identity and social structure of the Bantu Kavirondo. These ceremonies marked transitions from childhood to adulthood, marriage to parenthood, and eventually elderhood and death. Each stage of life was guided by customs, taboos, and rituals that ensured not only personal growth but also communal harmony.

A. Childhood and Naming

The life of a child began not just at birth, but in spiritual preparation:

- Pregnant women followed taboos to protect the unborn child — avoiding certain foods, places, and people.

- After birth, children were given names that reflected ancestral lineage, circumstances of birth, or clan history. For instance, names could recall hardships, blessings, or even dreams experienced by the mother during pregnancy.

Children were raised collectively — not just by parents, but by extended family, especially grandparents, older siblings, and maternal uncles.

B. Initiation of Boys: Circumcision and Age-Set Integration

Circumcision (khukhwalwa) was the most important rite of passage for boys among nearly all Bantu Kavirondo sub-tribes:

- Typically performed between the ages of 12 and 18, it marked the transition to manhood.

- The rite was not only physical but also spiritual and social, involving seclusion, instruction, and ceremonial reentry into the community.

Among groups like the Tiriki, Idakho, and Isukha, boys were placed into age-sets (ebiti or ebikinda) — rotating generational groups that formed military, work, and political alliances. These sets often bore symbolic names and were remembered across generations.

The number of teeth removed during initiation also varied:

- Four was common, but some groups (especially in Busia) removed two or six — and others, like the Luo, removed none.

C. Female Initiation

Female initiation was more variable across the Bantu Kavirondo:

- In some groups, girls underwent ritual seclusion and teaching without physical alteration.

- In others (particularly in areas with Sabaot or Maasai influence), female circumcision (FGM) was practiced, though it was not universal.

Initiated girls were taught about:

- Marriage expectations, cooking, child-rearing, and sexuality.

- Clan history, taboos, and how to manage communal responsibilities.

- Girls were often married shortly after initiation — though in some sub-groups, a longer period of courtship followed.

D. Marriage and Adulthood

Marriage was both a personal and clan-level contract:

- It involved bride price (emikalya), usually paid in livestock or labor.

- Marriage solidified alliances between clans and was often arranged through elders and maternal uncles.

Women moved to their husband’s homestead, though they maintained important ties to their natal family. In polygynous households, the first wife (omukhasi mukuru) held senior status and participated in key family decisions.

Adulthood brought with it economic responsibility, participation in clan councils, and eventual eligibility for elderhood.

E. Elderhood and Death

Elders (abakulu) were the keepers of memory, custodians of land, and judges of clan disputes:

- They were respected for their wisdom, ritual authority, and ability to mediate.

- Elders often officiated birth, initiation, marriage, and burial rituals, ensuring proper spiritual passage.

Death was not seen as an end but as a return to the ancestors. The dead were honored through:

- Burials within homesteads, usually near the main house.

- Ritual meals, songs, and annual remembrance ceremonies.

- Children sometimes received names of recently deceased relatives — linking generations spiritually.

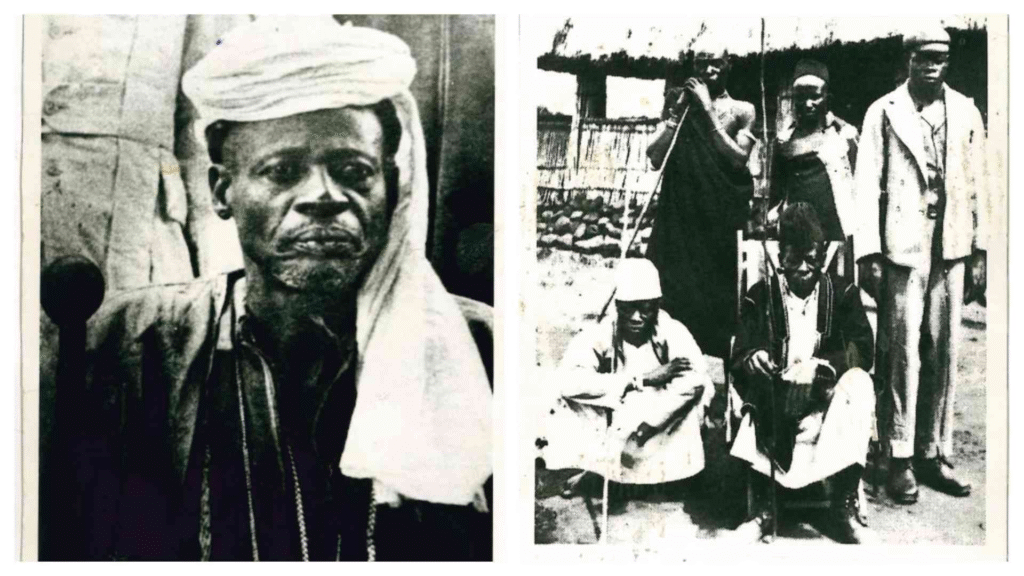

VIII. Colonial Contact and Transformation

The arrival of European colonial powers in the late 19th century marked a dramatic turning point in the lives of the Bantu Kavirondo. British administrators, missionaries, and settlers brought new systems of governance, religion, education, and economy — many of which clashed with, or tried to replace, indigenous ways of life. Yet the Bantu Kavirondo did not simply surrender their traditions; they adapted, resisted, negotiated, and reshaped their identities in response to colonial intrusion.

A. Early Encounters and British Occupation

By the 1890s, the British East Africa Company and later the colonial government began asserting control over the Lake Victoria basin. The Wanga kingdom, under Nabongo Mumia, played a crucial role in this process:

- Mumia formed an alliance with British administrators like Sir Frederick Lugard and Captain Hobley.

- In return, he was installed as paramount chief of the western region and given administrative authority over neighbouring Luhya and Luo groups.

This marked the beginning of indirect rule — where traditional leaders were used to enforce colonial policy, including:

- Tax collection

- Forced labor conscription

- Land alienation for settler use

While some groups benefited initially (e.g. the Wanga nobility), others, like the Tiriki and Kabras, resisted being ruled under Wanga authority, leading to internal tensions.

B. Missionaries and Christianity

Missionaries arrived almost immediately after colonial administrators. They built churches and mission schools in places like Kaimosi, Maseno, and Mumias:

- The Friends African Mission (Quakers) had a strong presence among the Tiriki and Maragoli.

- Catholic and Anglican missions were more dominant in Busia and Kakamega.

Missionaries:

- Introduced literacy and Christian education,

- Taught European hygiene and dress codes,

- Condemned traditional rituals such as initiation ceremonies, ancestral offerings, and polygamy.

Conversion to Christianity often divided communities — especially between “Christianized” youth and elders who held to ancestral traditions. Over time, many blended the two, creating syncretic practices that honored both.

C. Land, Labor, and Cash Economy

Colonial policies disrupted the traditional landholding systems of the Bantu Kavirondo:

- Land was declared Crown property, and vast areas were alienated for European farms.

- Poll tax and hut tax forced men to seek wage labor in settler farms, towns, and railway lines.

This led to:

- Labour migration of young men to Nairobi, Kericho, and even Uganda.

- Gender imbalance in villages, as women took over farming and child-rearing.

- Introduction of cash crops like cotton and maize — but often under exploitative schemes.

Communities that had long operated on a subsistence economy were now drawn into global markets, often as low-wage laborers or producers with little control over prices.

D. Education and the Rise of a New Elite

Mission schools created a new class of educated Africans, many of whom began to question colonial policies:

- Some became teachers, preachers, or clerks in government offices.

- Others became involved in early political movements, trade unions, and cultural associations — including the North Kavirondo Native Council and later the Kenya African Union.

This educated elite often became the bridge between colonial power and traditional society, advocating for land rights, education access, and cultural respect.

E. Resistance and Adaptation

Despite colonial pressure, many Bantu Kavirondo retained elements of their traditional culture:

- Rites of passage, including circumcision and clan rituals, continued, often in secret.

- Elders still governed local disputes through customary law, despite the imposition of colonial courts.

- Some groups, like the Tachoni and Bukusu, actively resisted colonial interference through movements like Dini ya Msambwa, which fused spiritual protest with cultural revival.

IX. Traditional Economy, Agriculture, and Crafts of the Bantu Kavirondo

The Bantu Kavirondo lived in a landscape rich in rivers, forests, and fertile soil — and they developed an economy rooted in mixed farming, livestock keeping, crafts, and local trade. Their livelihood was not just about survival; it was deeply tied to culture, kinship, and ritual life. Every economic activity — from hoeing a field to brewing beer — was embedded in social meaning and spiritual belief.

A. Agriculture: The Foundation of Life

Farming was central to the Bantu Kavirondo economy:

- They practiced shifting cultivation and later permanent farming once land pressure increased.

- Main crops included:

- Finger millet (obulo) and sorghum — used in food and brewing.

- Bananas, sweet potatoes, beans, pumpkins, and later maize (introduced after contact with the Portuguese and Arabs).

- Vegetables such as cowpeas, amaranth (litoto), and spider plant (tsimboka).

Women were primarily responsible for planting, weeding, and harvesting, while men cleared new fields and dug granaries.

Farming was not just economic — it was ceremonial:

- Planting began with ritual blessings and ancestral invocations.

- Harvests were marked by thanksgiving ceremonies and feasts.

B. Livestock and Animal Husbandry

Cattle (ebisimba) were highly valued — not just for meat and milk, but as:

- Symbols of wealth,

- Bride price payments,

- Ritual sacrifices,

- And indicators of social status.

Other animals included:

- Goats and sheep for daily use and minor rituals,

- Chicken (especially hens) for offerings and daily meals,

- Dogs and occasionally pigs in certain sub-tribes.

Livestock were cared for by young boys and older men, who ensured protection from disease, theft, and predators.

C. Hunting, Fishing, and Gathering

While agriculture dominated, supplementary activities were vital:

- Hunting provided bushmeat like antelope and warthog, especially among forest-dwelling groups like the Tiriki.

- Fishing was central among lakeside and riverine communities like the Samia, Bunyala, and Khayo.

- Gathering of wild fruits, honey, mushrooms, and medicinal herbs was done by women, children, and specialist herbalists.

These activities sustained food diversity and were often tied to ritual taboos (e.g., who could eat certain meats or fish during specific seasons).

D. Craftsmanship and Technology

The Bantu Kavirondo were skilled in several crafts:

- Ironworking: Local smiths made hoes, knives, spears, and ornaments from iron ore, often smelted in small clay furnaces.

- Pottery: Women crafted cooking pots, water jars, and ritual vessels using local clay, molded by hand and fired in open pits.

- Weaving and basketry: Made from reeds, banana fibre, and palm — used for storage, winnowing, and carrying.

- Woodworking: Carpenters fashioned stools, mortars, pestles, and ritual drums.

These crafts were not simply utilitarian — they reflected clan identities, generational skills, and spiritual symbolism. For example, certain carvings were reserved for elders or spirit-mediums.

E. Trade and Exchange

Trade was mostly local and regional, based on barter:

- Communities traded millet for fish, iron for livestock, or beer for cloth.

- Markets were often held on designated days, and some became inter-ethnic hubs — especially in border areas shared with Luo, Teso, or Kalenjin communities.

Colonialism introduced coin-based currency and larger markets, but traditional barter and local exchange remained common well into the 20th century.

X. Modern Cultural Survival and Revival

In the face of colonization, modernization, Christianity, and global economic change, the Bantu Kavirondo — now largely identified as the Luhya — have shown remarkable resilience in preserving and adapting their cultural identity. Far from being frozen in the past, their traditions have evolved to meet the realities of post-independence Kenya, while retaining strong links to ancestral values and customs.

A. Language Retention and Revival

Despite decades of educational policy favoring English and Kiswahili, many Bantu Kavirondo communities have retained their mother tongues, especially in rural areas:

- Languages such as Luwanga, Lulogooli, Lutiriki, and Lunyala are still spoken at home, in marketplaces, and in community events.

- Radio stations, church services, and local plays have increasingly used Luhya dialects to reach wider audiences and preserve local identity.

Efforts by local writers, teachers, and cultural organizations have also promoted literacy in local languages, preserving folktales, proverbs, and oral history in written form.

B. Ritual and Ceremony in Contemporary Life

While some traditional practices have declined, many remain deeply embedded in daily life:

- Circumcision ceremonies, especially for boys, are still practiced widely in sub-counties such as Bungoma, Vihiga, and parts of Kakamega, though often adjusted to modern health standards.

- Marriage negotiations (bride price, clan involvement) continue, blending traditional norms with Christian ceremonies.

- Funerals remain profoundly traditional, often involving extended vigils, ancestral invocations, and clan-wide gatherings that reinforce lineage ties.

Additionally, seasonal festivals and initiation songs and dances have been revived in cultural forums and school competitions, helping the youth reconnect with their heritage.

C. Cultural Institutions and Advocacy

Cultural survival has been boosted by:

- County cultural offices, especially after Kenya’s 2010 Constitution devolved governance and empowered local communities.

- Organizations like the Maragoli Cultural Festival, Luhya Council of Elders, and Isukuti dance troupes, which promote cultural pride, historical awareness, and intergenerational dialogue.

- The UNESCO recognition of the Isukuti dance as intangible cultural heritage has inspired further efforts to document and preserve oral traditions, music, and dress.

These institutions also serve as mediators of change, helping communities balance tradition with modernity — such as adjusting age-old taboos in light of gender equity and health education.

D. Intergenerational Dialogue and Identity

In today’s context of urbanization and globalization, many young people of Luhya descent grow up speaking Kiswahili or English first. However:

- Family stories, clan affiliations, and community events still provide a cultural grounding.

- Names, initiation, and funerals often serve as bridges between elders and youth, enabling cultural transmission even in urban settings like Nairobi, Eldoret, or Mombasa.

- Social media platforms have also become spaces where youth discuss identity, clan names, and dialect — often seeking digital forms of belonging.

E. Challenges to Cultural Continuity

Despite these efforts, the Bantu Kavirondo face several ongoing challenges:

- Loss of land and ecological degradation threaten sacred sites and traditional farming practices.

- Religious tensions sometimes arise between evangelical Christian doctrines and traditional rites, especially during funerals or healing rituals.

- Generational gaps in cultural knowledge continue to widen where elders are not empowered to teach, or where school systems ignore local histories.

However, the overall trend shows cultural flexibility, not collapse — a capacity to reinterpret old ways in modern contexts without losing core values.

Conclusion: The Enduring Legacy of the Bantu Kavirondo

The history of the Bantu Kavirondo — now recognized broadly under the Luhya identity — is a story of deep roots, migration, adaptation, and resilience. From their early arrival in western Kenya in the 14th to 15th centuries, these communities carved out a place for themselves through farming, ritual, and kinship. Long before the arrival of the Luo or European colonists, they had established thriving social systems, diverse dialects, and sacred relationships with the land.

Colonialism disrupted much of this foundation, but it did not erase it. Faced with taxes, land alienation, missionary pressure, and imposed chiefs, the Bantu Kavirondo adapted strategically — sometimes cooperating, other times resisting. Through these challenges, they preserved their language, rituals, and systems of justice, even as they contributed to the making of the modern Kenyan state.

Today, the cultural heartbeat of the Bantu Kavirondo is still alive — in ceremonial songs, clan stories, circumcision rites, and community gatherings. Their traditions continue to evolve, shaped by cities, education, religion, and digital media, yet grounded in the ancestral wisdom of their forebears.

This journey — from ancestral migration to modern cultural revival — reveals a people who have never been mere spectators in history. They have shaped, resisted, negotiated, and transformed it at every stage. The legacy of the Bantu Kavirondo is not just found in books or museums, but in the living memory of a people who carry the past into the present with pride and purpose.