Causes of the Uprising

The Mau Mau Uprising was rooted in long-standing grievances among the Kikuyu and other communities over land dispossession, lack of political rights, and social inequalities under British colonial rule.

- Land Dispossession

By 1950, over 1.25 million Kikuyu had been confined to “reserves” making up just 7% of Kenya’s arable land, while European settlers controlled the fertile central highlands known as the “White Highlands.” This led to deep frustration, especially among landless young men. - Labor Exploitation and Discrimination

Africans were paid low wages and denied meaningful advancement in colonial society. European settlers had near-total control over labor laws, wages, and land access. - Political Exclusion

Africans were not allowed full political participation. The rise of educated African leaders (e.g., Kenyatta, Mboya) created new political expectations that clashed with colonial intransigence. - Urban and Social Stress

Rapid urbanization led to overcrowding and unemployment, especially in Nairobi. Disillusioned youth became key recruits into Mau Mau movements, many of which had grown from previous secret societies and land-rights organizations like the Kenya African Union (KAU). - Cultural and Spiritual Dimensions

Oathing rituals and spiritual resistance became a way to reclaim Kikuyu identity and solidarity, drawing from traditions but adapting to political resistance.

“It was not simply a rebellion of peasants. It was also a battle of meaning: about land, rights, and justice.” – Anderson (2005)

Key Events (1952–1960)

- 1952: State of Emergency Declared

Following the assassination of Chief Waruhiu in October, the British declared a State of Emergency. Key nationalist leaders, including Jomo Kenyatta, were arrested even though there was little evidence linking them directly to Mau Mau activity. - 1953: Lari Massacre and Mass Detentions

In March, Mau Mau fighters killed over 70 loyalists in Lari. In retaliation, colonial forces executed hundreds and burned villages. Mass detentions began, with over 80,000 Africans eventually imprisoned in camps without trial. - 1954: Operation Anvil

A huge military and police operation in Nairobi aimed to root out Mau Mau networks. Over 20,000 people were detained. The operation militarized the city and introduced curfews and ID systems. - 1955–1956: Forest Campaigns

British troops, African loyalists, and home guards launched intense operations against Mau Mau fighters hiding in the Aberdare and Mt. Kenya forests. General Dedan Kimathi, the leading Mau Mau military commander, was captured in October 1956 and hanged in 1957. - 1957–1959: Decline and Aftermath

With leadership decimated and supplies cut off, Mau Mau resistance faded. However, Kenya’s political landscape had shifted. African representation was increased, and settler dominance began to weaken. The Emergency was officially lifted in 1960.

A Police Patrol Checking A Road In The Neighborhood Of Nairobi In Kenya When Some Mau Mau Activists Were Sought Around 1952-1956.

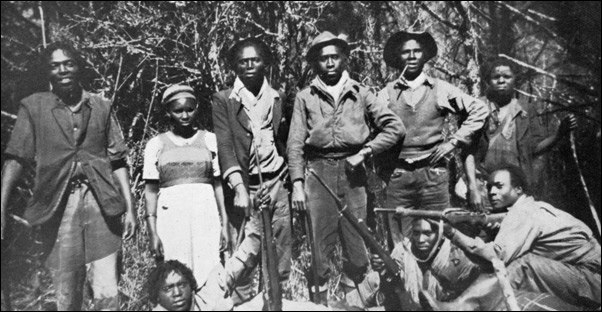

L to R: James Gichuru, Harry Thuku, Snr. Chief Koinange, Eliud Mathu, Jomo Kenyatta, Senior Chief Waruhiu,and Chief Josiah Njonjo. At the rally, they denounced Mau Mau and suggested a conciliatory approach

British Response

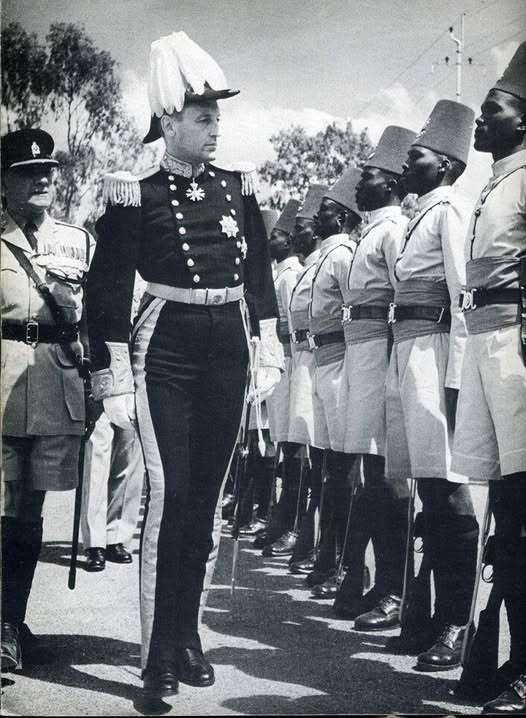

The colonial response was a mix of military, psychological, and administrative strategies:

- Counter-Insurgency Tactics

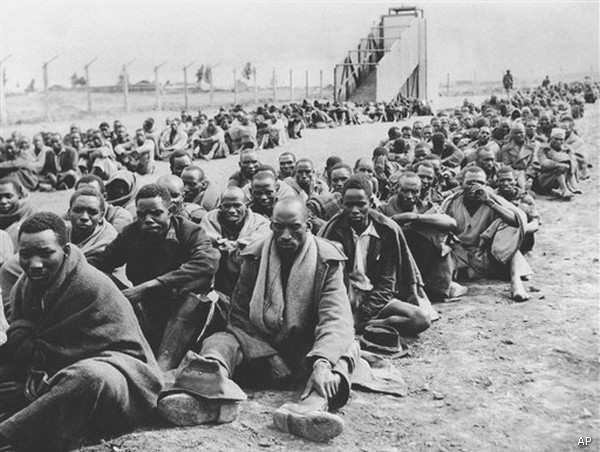

The British deployed over 50,000 troops and 20,000 colonial police. Villages were relocated into “villagization schemes” that acted like open-air prisons. - Detention Camps

Tens of thousands of Kikuyu were held in brutal camps such as Manyani, Hola, and Langata. Torture, forced labor, and executions were widespread. Caroline Elkins documents systemic abuse and efforts to cover it up in Imperial Reckoning.

“The colonial government detained a greater proportion of Kenya’s population than any other colony in British Africa.” – Elkins (2005)

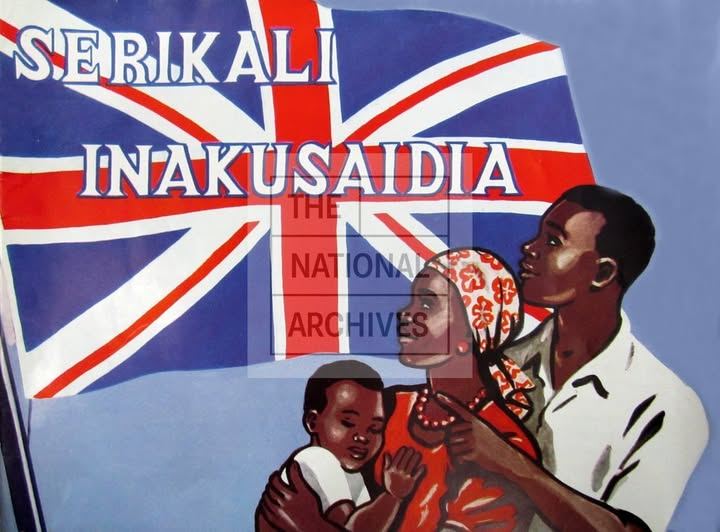

- Propaganda and Psychological Warfare

Films, leaflets, and radio were used to paint Mau Mau as irrational terrorists, masking their political motives.

Under the villagisation programme begun in mid-1954, nearly a million Kikuyu were forcibly resettled into some 800 fenced and trench-lined villages across the Central Province. These “protected villages” were surrounded by spike-bottomed trenches and barbed wire, and were garrisoned by Home Guard units (often drawn from the same communities) to cut off Mau Mau supply lines and support.

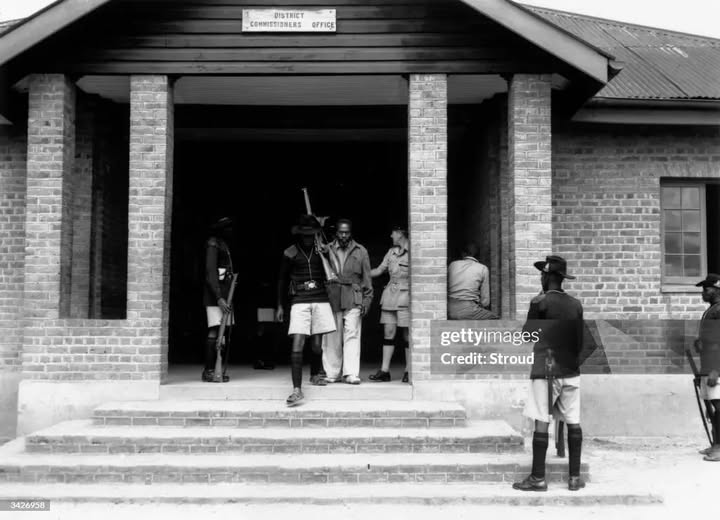

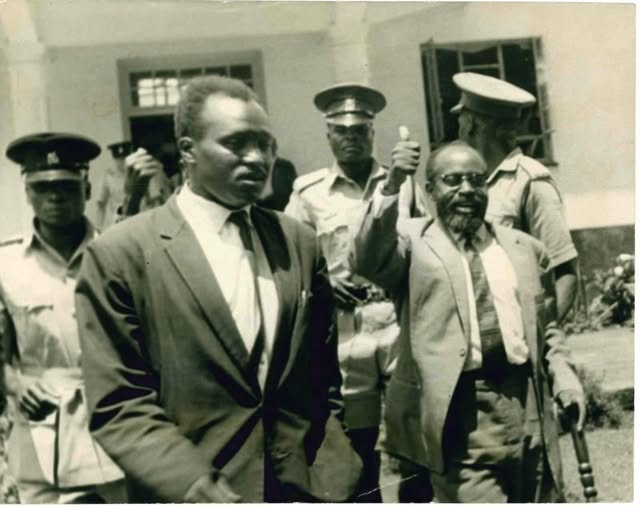

19th November 1952: Future Kenyan president Jomo Kenyatta (c.1891 – 1978) being led out of the District Commissioner’s Office in Kenya

African Resistance

While the Mau Mau movement is most associated with the Kikuyu, it involved members from the Embu, Meru, and parts of the Kamba as well.

Hidden in plain sight along Nairobi’s Kirinyaga Road, Kiburi House stands as a quiet giant of history. Likely the first building in Nairobi’s CBD to be owned by an indigenous Kenyan, it became much more than a property. Acquired by Richard Macharia in 1950, Kiburi House quickly turned into a center of political awakening — hosting the Kenya African Union, powerful trade unions, MAU MAU and underground publications

- Forest Fighters

These were the armed wing, living in harsh forest conditions and organizing ambushes. Kimathi’s group created codes of discipline and war, operating like a guerrilla army. - Civilian Support

Women and elders served as spies, food carriers, and message runners. Many paid the price with detention, torture, or death. - Urban Activists

Sympathizers in Nairobi and other towns offered shelter, funds, and support networks. Many faced arrests under laws like the Emergency Powers Ordinance. - Loyalist Opposition

Not all Africans supported Mau Mau. Some became loyalist chiefs, home guards, or soldiers, and were seen as collaborators. This created deep social rifts that still linger.

circa 1953: A view of part of Nairobi, the capital of Kenya, now interlaced with barbed wire and sandbag barricades to keep it safe from the Mau Mau. The Mau Mau are a secret society formed among the Kikuyu people of Kenya. (OC)

Legacy

The Mau Mau uprising accelerated decolonization and fundamentally challenged British moral authority in Kenya. Though long painted as terrorists, the Mau Mau were officially recognized as freedom fighters by the Kenyan government in 2003. In 2013, the British government formally acknowledged torture in the camps and paid compensation to survivors.

“Mau Mau made it impossible to continue with colonialism as usual.” – Charles Hornsby (2012)

Kaggia was a part of the political wing of the Mau Mau, and was imprisoned as one of the Kapenguria 6. An ardent Socialist, Kaggia campaigned for economic freedom, both pre and post independence, a stance that led to his enmity with the capitalists in KANU

Key Mau Mau Figures and Their Biographies

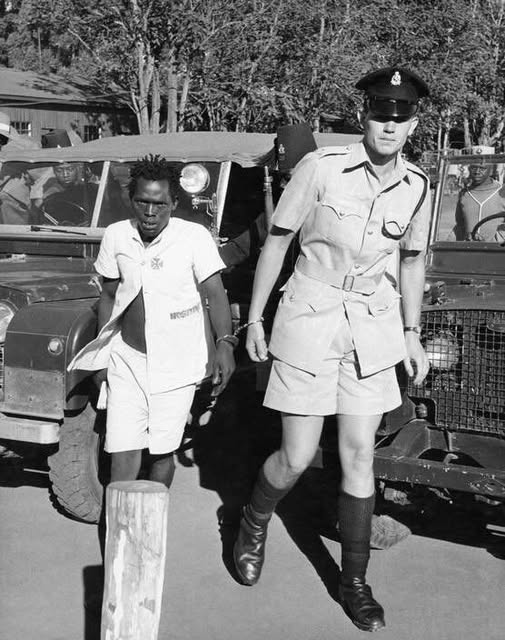

Chained hand and foot, Mau Mau leader General Kaleba is marched to a waiting plane at Nairobi Airport in 1954. A key figure in the resistance, Kaleba was later tried and executed in Nyeri for the killing of settler Gray Leakey.

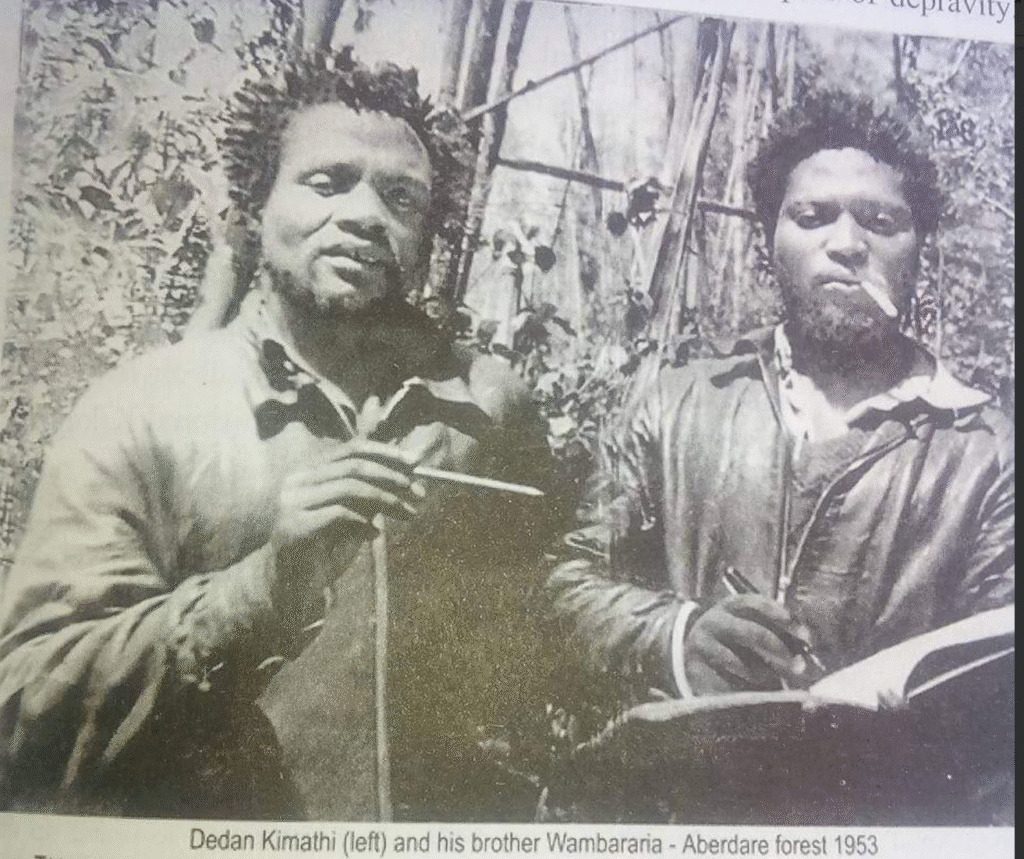

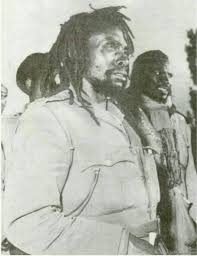

Dedan Kimathi Waciuri (c. 1920–1957)

Role: Field Marshal and ideological leader of Mau Mau forest fighters.

Born in Tetu, Nyeri District, Kimathi was educated in mission schools and briefly worked with the King’s African Rifles. He founded the Itungati, a militant nationalist group in Tetu, and developed a decentralized military structure for Mau Mau fighters. By 1953, he began styling himself “President of the Ituma” (council of warriors), pushing for a strict command code and forest discipline (MacArthur, 2017, pp. 34–38).

He clashed with other leaders, including Stanley Mathenge, and accused several of treason. Kimathi was captured on 21 October 1956, tried for possession of a revolver, and executed on 18 February 1957 despite arguments that he was attempting to surrender (MacArthur, 2017, pp. 203–212). His prison diary reflects a sharp political mind and unwavering commitment to Kenyan liberation.

Citation:

MacArthur, J. (Ed.). (2017). Dedan Kimathi on trial: Colonial justice and popular memory in Kenya’s Mau Mau rebellion. Ohio University Press.

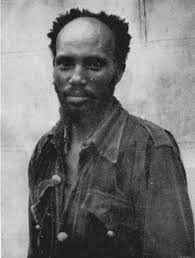

Waruhiu Itote (“General China”) (1922–1993)

Role: Senior commander in Mount Kenya region; later collaborator.

Itote was a World War II veteran who became one of Mau Mau’s most respected fighters before his capture in 1954. Under British custody, he revealed operational details and later participated in surrender negotiations with fighters under Operation Wedgewood, often writing as “Constable Wambu” (Rankin, 2022, pp. 168–173). Although sentenced to death, his cooperation spared his life. His memoir, Mau Mau General, is a controversial source due to his betrayal of Kimathi.

Citation:

Rankin, N. (2022). Trapped in history: Kenya, Mau Mau and me. ibidem-Verlag.

Stanley Mathenge wa Mirugi

Role: Aberdares-based military commander; rival to Kimathi.

Mathenge led a large force in the Aberdare forests and advocated for a more autonomous command structure. In 1955, he reportedly sought surrender talks with the colonial government without consulting Mau Mau’s central leadership, prompting Kimathi to issue his arrest (MacArthur, 2017, pp. 129–132). He vanished shortly after, sparking decades of speculation. In 2003, the Kenyan government mistakenly introduced an Ethiopian man as Mathenge, later debunked as an impostor (Rankin, 2022, p. 8).

Citations:

MacArthur, J. (Ed.). (2017). Dedan Kimathi on trial: Colonial justice and popular memory in Kenya’s Mau Mau rebellion. Ohio University Press.

Rankin, N. (2022). Trapped in history: Kenya, Mau Mau and me. ibidem-Verlag.

Kikuyu Women’s Leadership in Mau Mau

Key Figures: Rebecca Njeri Kairi, Priscilla Wambaki, Wambui Wagarama, Mary Nduta.

These women were deeply embedded in Mau Mau’s logistics and intelligence networks. Operating in districts like Kiambu, they organized oath-taking ceremonies, carried food and arms into forests, and served as informants and recruiters. The British colonial state acknowledged them as central figures in sustaining the resistance (Presley, 1992, pp. 126–138).

Their activities disrupted traditional gender roles and transformed the political status of Kikuyu women in postcolonial Kenya. Many faced imprisonment under harsh conditions, and their participation was long erased from nationalist memory until oral history projects recovered it (Presley, 1992, pp. 150–162).

Citation:

Presley, C. A. (1992). Kikuyu women, the Mau Mau rebellion, and social change in Kenya. Westview Press.

Karari Njama (b. 1926)

Role: Political leader, Secretary of the Kenya Parliament in the forest, later Minister of War.

Karari Njama was born in Laikipia to squatter parents on a Boer settler’s farm. His early life exposed him to settler injustice and sparked his political awareness (Barnett & Njama, 1966, pp. 81–83). After resigning from teaching, he joined the Mau Mau and became deeply involved in its forest-based operations. He took successive oaths—the Unity Oath, Warrior Oath, and Leader’s Oath—before joining the forest at Kigumo Camp (Barnett & Njama, 1966, pp. 117–143).

He rose through the ranks to become Chief Secretary of the Kenya Parliament in the forest and eventually Minister of War before being wounded and captured (Barnett & Njama, 1966, pp. 339–487).

Citation:

Barnett, D. L., & Njama, K. (1966). Mau Mau from within: An analysis of Kenya’s peasant revolt. Monthly Review Press.

General Tanganyika

Role: Commander of Mount Kenya units.

A critical figure in forest diplomacy, General Tanganyika was captured while carrying letters from Kimathi and Njama inviting negotiations. The British later released him (but not General China) to convince Mount Kenya fighters to surrender (Barnett & Njama, 1966, pp. 353–354)Mau Mau from Within An ….

His mission ended in failure; the Nyandarua-based Kenya Parliament opposed surrender terms and moved to sever coordination with Mount Kenya forces unless independently verified.

General Kahiu-Itina

Role: Field commander, Nyandarua front.

Kahiu-Itina was a close associate of Karari Njama, leading joint movements during leadership meetings and representing Nyandarua in critical gatherings (Barnett & Njama, 1966, p. 305). His command zone bordered that of Kimathi, and he acted as both military strategist and local negotiator.

Colonel Gitau Icatha

Role: Senior officer and internal security head in Kimathi’s camp.

He supervised security in Kimathi’s main headquarters and facilitated sensitive visits such as that of Karari Njama and Kahiu-Itina (Barnett & Njama, 1966, pp. 305–306).

General Rui and General Kariba

Role: Coordinators of communication between Mount Kenya and Nyandarua regions.

They were responsible for logistical coordination and acted as liaisons during periods of fractured leadership. They also guided fighters between regions during crises of trust between districts (Barnett & Njama, 1966, p. 353)Mau Mau from Within An ….

General Kimemia, General Kimbo, and Mbaria Kaniu

Role: Regional commanders with independent followings.

These figures controlled their own sections of the forest and commanded loyalty from sub-units that often overrode centralized command. This created internal tensions and weakened unified decision-making (Barnett & Njama, 1966, p. 305)