Nyeri is a place where Kenya’s history folds in on itself. It is both the pride of the White Highlands and the birthplace of the Mau Mau rebellion. It gave the country presidents, bishops, and generals, but also sent thousands of its sons and daughters into detention camps and forests. If Nairobi was the swamp that became a capital, Nyeri was the ridges that became a battlefield.

A Town at the Crossroads of Power and Rebellion

This town, perched at the base of Mount Kenya and staring into the Aberdares, has lived many lives. To the British, it was prime land for coffee, cattle, and conquest. To the Kikuyu, it was home, sacred soil tied to ancestors and sustenance. To the Mau Mau, it was the frontline of war. And to the independent republic, it became the county of presidents. Nyeri is Kenya in miniature: wealth and violence, power and betrayal, faith and rebellion, all layered into one landscape.

The Land Before the Empire

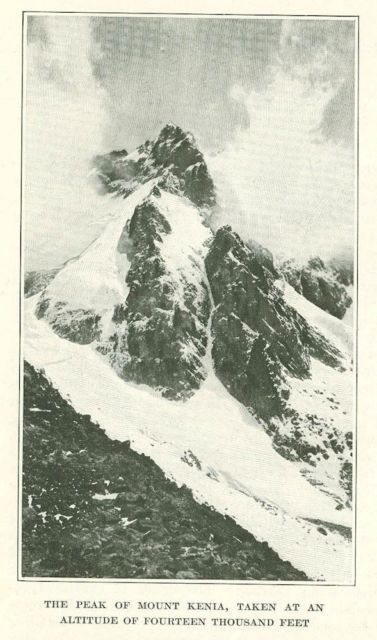

Before the empire staked its claims, Nyeri was Kikuyu country — fertile ridges carved into terraces of bananas, millet, and maize. Families tended goats and sheep, and clans organized life through kinship, elders’ councils, and age-set rituals. To the Gikuyu, land was not just property; it was the source of life, the gift of Ngai, God, who dwelt atop the snow-capped peak of Mount Kenya.

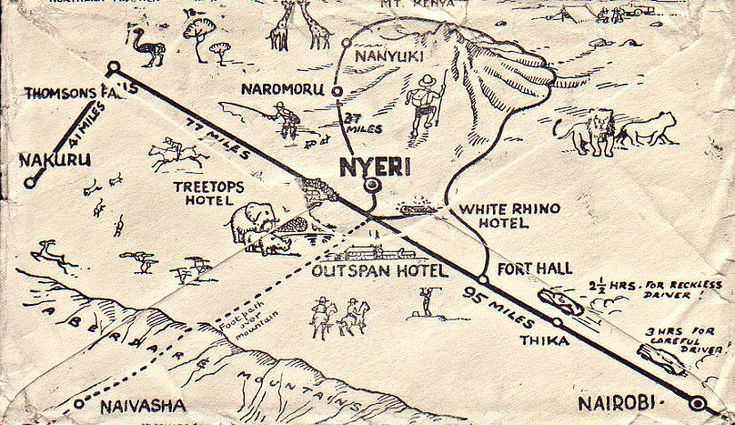

Nyeri sat at a crossroads. To the east rose Kirinyaga (Mount Kenya), sacred and forbidding. To the west lay the Aberdare forests, thick with elephants, buffalo, and spirits. To the south, the Maasai roamed the grasslands with their cattle, pushing against Kikuyu boundaries. To the north, the Embu and Meru carved their own territories. Nyeri was thus both fertile homeland and frontier, a place where the Kikuyu defended their ridges and negotiated alliances with neighbors.

It was not isolated. Trade routes wound through Nyeri’s hills long before Europeans appeared. Salt, iron, beads, and livestock moved from one ridge to another. Songs and stories traveled too, carrying news of distant raids and rituals. The community was tight-knit but outward-looking, ready to absorb and adapt.

This balance shattered when the first colonial surveyors appeared at the turn of the 20th century. To them, Nyeri was not sacred ground but real estate — cool climate, rich volcanic soil, and perfect altitude for European crops. What Ngai had given, the empire was about to take.

The Coming of the British

When the British looked at Nyeri, they didn’t see sacred ridges or ancestral homelands. They saw altitude, soil, and climate — the perfect ingredients for a European paradise in Africa. Around 1902, colonial surveyors planted their flags on Nyeri’s slopes, declaring it part of the “White Highlands,” a term that said everything about who was welcome and who was not.

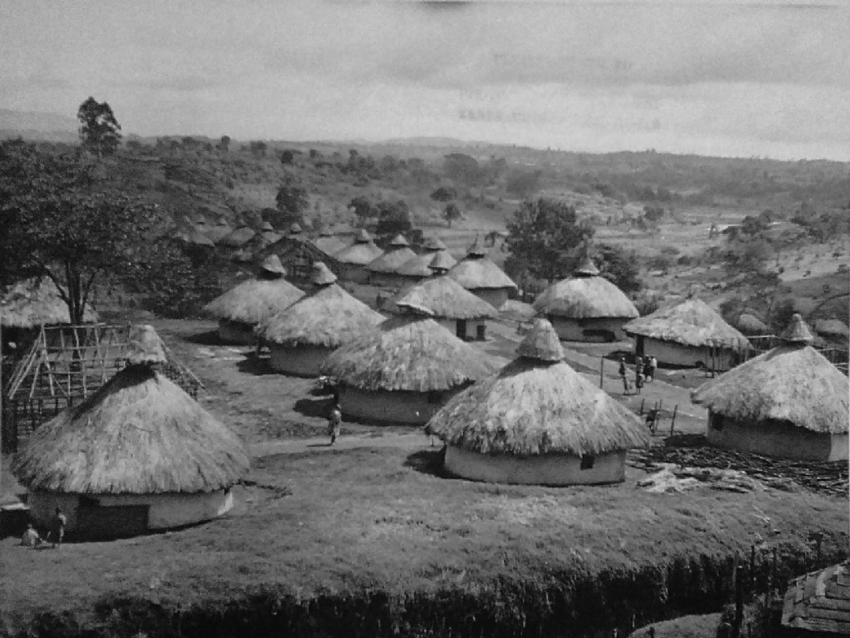

The Kikuyu who had lived on this land for generations were suddenly strangers in their own home. Colonial ordinances carved up Nyeri into settler farms, while Africans were herded into “reserves” on the less fertile margins. What had once been a system of communal tenure became fenced-off property deeds written in a language the dispossessed could not read.

The British brought in coffee seedlings and cattle, turning Nyeri into an agricultural colony. The rolling ridges that had fed generations now fed the empire’s export economy. Africans were not invited to share in the harvest; they were conscripted to labor on it. Hut tax and poll tax ensured that families who resisted wage labor would be forced to pay cash they didn’t have, pushing them into settler farms or road-building crews.

Nyeri town itself began as a colonial administrative outpost. It was no accident that it sat between the Aberdares and Mount Kenya — two forests that would later become Mau Mau hideouts. The empire always built its watchtowers where the land was richest and the people most restless. By the 1910s, Nyeri had European-style bungalows, mission stations, and barracks, while Africans crowded into makeshift villages on the edges.

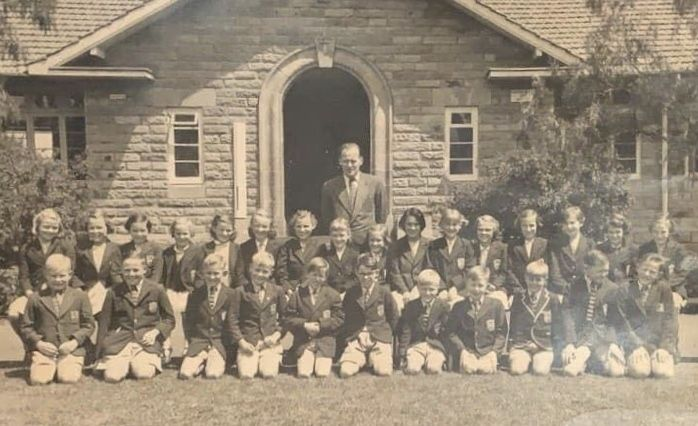

The Consolata missionaries soon followed, laying foundations for schools, hospitals, and churches. They built the iconic Mathari Mission and Our Lady of Consolata Cathedral, which still dominate Nyeri’s skyline. Christianity marched hand in hand with colonial authority, promising salvation while teaching obedience.

By the 1920s, Nyeri was firmly in settler hands: fertile farms, a growing colonial town, and an African population increasingly squeezed between labor demands and loss of land. What looked like progress to the empire felt like theft to the Kikuyu. The seeds of rebellion had been planted, and they would take root in Nyeri’s ridges.

Nyeri as a Colonial Hub

By the 1920s, Nyeri had become the empire’s little garden town. The settlers called it a highland paradise — cool weather, rolling ridges, and fertile volcanic soil that yielded coffee and tea with near-religious abundance. On weekends, they gathered in country clubs, sipped gin, and congratulated themselves on their civilizing mission, all while Kikuyu tenants tilled the land just beyond the fences.

Nyeri town itself grew around the district commissioner’s office, the barracks, and the missions. It was the kind of place where a colonial officer could buy fresh milk in the morning, hold court cases by noon, and hunt in the Aberdares by afternoon. The town plan was segregated by design: Europeans in spacious bungalows, Asians running the shops and businesses, and Africans pushed into crowded “native locations” with limited services.

The Consolata missionaries left a particularly deep imprint. They built Mathari Mission Hospital, schools, and the imposing Our Lady of Consolata Cathedral. For many, Christianity became a path to literacy and modern medicine; for others, it was a cultural Trojan horse, replacing ancestral traditions with European morality. Yet the missions also produced some of Nyeri’s earliest educated Africans, the very people who would later question colonial authority.

Education became a double-edged sword. Schools in Nyeri produced clerks and teachers for the colonial system, but they also created a class of Africans who could articulate grievances in English, write petitions, and eventually lead protests. What the British imagined as assimilation often turned into resistance.

Still, Nyeri was no Nairobi. It was quieter, more provincial, the kind of town where empire’s order seemed secure. But just beyond the ridges lay forests that empire could not tame. By the 1940s, whispers of discontent spread from one ridge to another. The land alienation, the forced labor, the humiliations of colonial justice — all were boiling beneath Nyeri’s polished surface. When rebellion came, it would not come from Nairobi’s streets but from the forests and ridges around Nyeri.

Resistance and Mau Mau

Nyeri’s ridges were fertile not just for coffee but for rebellion. By the late 1940s, land alienation, forced labor, and racial humiliation had turned discontent into organization. The Kikuyu Central Association and later underground networks began mobilizing in whispers, oaths, and forest meetings. Nyeri, sitting between the Aberdare range and Mount Kenya, was geographically perfect for insurgency — a town at the edge of two vast natural fortresses.

When the Mau Mau uprising erupted in 1952, Nyeri became its beating heart. Fighters like Dedan Kimathi and General China moved through the Aberdares, raiding settler farms, striking police posts, and disappearing back into the forest. From Nyeri’s ridges, supplies, intelligence, and recruits flowed into the movement. The colonial government saw Nyeri not as a sleepy highland town anymore, but as the epicenter of rebellion.

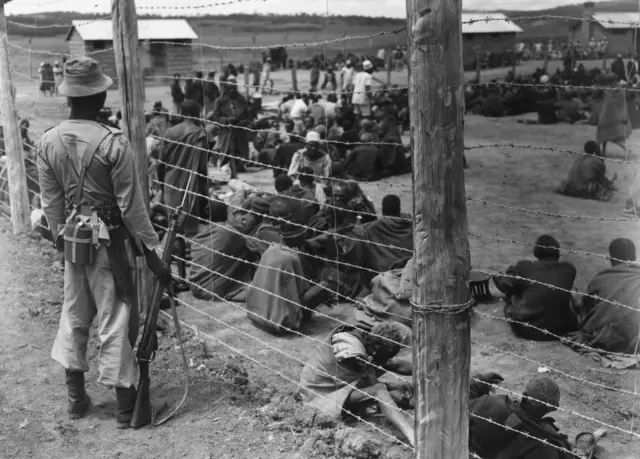

The British response was ferocious. Nyeri became a hub of the detention camp system — makeshift prisons where thousands of Kikuyu were confined, interrogated, and tortured. Villages were fenced in with barbed wire, curfews imposed, and collective punishment became routine. The empire turned Nyeri into a laboratory of counterinsurgency, echoing the methods it had used in India, Malaya, and Ireland.

The forests themselves became mythic. To the fighters, they were sanctuaries where oaths bound men and women to a vision of freedom. To the British, they were lairs of “terrorists” who had to be smoked out like vermin. The contrast was stark: what one side called freedom fighters, the other called savages.

It was near Nyeri, in 1956, that the rebellion’s most iconic figure, Dedan Kimathi, was finally captured. Wounded and betrayed, he was taken to court in Nyeri and later hanged at Kamiti Prison. His execution was meant to break the rebellion; instead, it made him a martyr. To this day, his name is whispered in Nyeri as both pride and wound — the son of the ridges who faced an empire with nothing but a rifle, a notebook, and an unshakable belief that the land must be free.

By the time the Emergency ended in 1960, Nyeri had been remade. Thousands dead, entire communities traumatized, but the idea of independence was irreversible. The ridges had paid a heavy price, and history would not let them forget.

Independence and Political Power

When independence finally came in 1963, Nyeri stood at the center of both pride and paradox. The ridges that had birthed Mau Mau martyrs also became the backbone of the new republic’s political elite. Land was returned, yes — but much of it went not to the peasants who had bled in the forests, but to a new African middle class and political barons. For many in Nyeri, Uhuru felt less like liberation and more like a transfer of titles from one ruling hand to another.

Yet Nyeri also became synonymous with political power. Its sons and daughters climbed into State House, Parliament, and pulpits. Most famously, Mwai Kibaki, born in Othaya, rose from economics lecturer to president of Kenya (2002–2013). His leadership, technocratic and aloof, reflected a Nyeri style of politics: pragmatic, calculating, and quietly dominant.

Even before Kibaki, Nyeri had become a stronghold of central Kenya’s political influence. The region supplied ministers, civil servants, and church leaders who shaped the course of postcolonial Kenya. From Nyeri’s hills, decisions rippled across the nation. Nairobi might have been the capital, but Nyeri was the wellspring of political capital.

The irony was never far away. The home of Dedan Kimathi, executed by the British, became the home of presidents who often downplayed Mau Mau’s legacy. For decades, fighters and their families were left in poverty, their sacrifices sidelined in official narratives. It wasn’t until Kibaki’s presidency that Kenya officially recognized Kimathi with a statue in Nairobi. In Nyeri itself, memory remained sharper than the politics — the ridges never forgot that independence had come unevenly, with some rewarded and others abandoned.

Nyeri was also deeply religious, producing Catholic bishops and Protestant leaders whose pulpits shaped moral debates. The Catholic Consolata missions had made Nyeri a spiritual hub, and by the late 20th century, it was known both for producing presidents and priests. Political power and divine authority often overlapped on the ridges.

By the 1970s and 80s, Nyeri’s name carried weight. It was shorthand for central Kenya’s dominance in the state. But it was also shorthand for the contradictions of Uhuru: a land of martyrs and presidents, rebellion and privilege, glory and ghosts.

Religion and Education

If empire planted guns in Nyeri, the missionaries planted crosses and blackboards. The Consolata Fathers had arrived early in the 1900s, building schools, hospitals, and churches that reshaped the ridges. They left behind monuments that still dominate Nyeri’s skyline: Our Lady of Consolata Cathedral, Mathari Mission Hospital, and schools like Kagumo and Nyeri High.

Christianity spread quickly, stitched into daily life with hymns, catechism classes, and the promise of literacy. For some, it was salvation; for others, it was cultural conquest, the steady erasure of ancestral rituals. Yet paradoxically, these very schools produced some of the sharpest critics of colonial rule. The empire educated its gravediggers, and Nyeri’s classrooms turned farmers’ sons into clerks, teachers, and eventually revolutionaries.

Religion remained powerful even after independence. Nyeri became a Catholic stronghold, producing bishops, priests, and later even saints — among them Blessed Irene Stefani “Nyaatha”, the Italian Consolata nun who served in Mathari. Faith and politics intertwined on the ridges, pulpit and parliament echoing one another.

Nyeri Today

Today, Nyeri is both museum and marketplace. It is the gateway to the Aberdares and Mount Kenya, attracting tourists who want to see the forests where Mau Mau once hid or to visit the grave of Robert Baden-Powell, founder of the Scouts, who chose Nyeri as his final resting place.

Monuments to Dedan Kimathi stand alongside colonial-era churches, and statues of presidents overlook markets where small traders still hustle for survival. The contradictions remain: rich volcanic farms alongside stories of Mau Mau widows still waiting for justice; the memory of martyrdom side by side with the legacy of presidential privilege.

Economically, Nyeri thrives on tea, coffee, and dairy — the same cash crops that once made it a settler paradise. Its schools continue to produce leaders, and its churches remain influential. Yet its history lingers everywhere, in names etched on graves, in forests thick with ghosts, in ridges that whisper of rebellion and betrayal.

Recommended Next Reads

- Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya, 1952–1960

— Nyeri was the crucible of Mau Mau. This deep dive complements the rebellion stories of Dedan Kimathi and the Aberdares. - Kikuyu Protest Songs During the Mau Mau Period: The Melody of Rebellion

— A cultural companion to Nyeri’s forests, showing how Kikuyu music carried the spirit of resistance. - Kenya’s White Highlands: Land, Race, and the Economics of Exclusion

— Explains the land alienation that turned Nyeri from fertile Kikuyu ridges into settler farms — the grievance at the heart of the Emergency. - Unveiling the Rich Heritage of the Kikuyu People

— Complements Nyeri’s precolonial section, giving readers a deeper look into Kikuyu traditions, land, and cosmology.

Conclusion: Nyeri, Between Glory and Ghosts

Nyeri is not just another highland town. It is the soil where empire took root and where rebellion sprouted. It is the birthplace of Dedan Kimathi, martyr of Mau Mau, and of Mwai Kibaki, architect of modern Kenya’s economy. It is where the cross and the rifle clashed, where missions preached obedience while forests harbored freedom fighters.

To walk through Nyeri is to walk a tightrope across Kenya’s contradictions. On one side, pride: presidents, churches, fertile land, and schools that shaped a nation. On the other, ghosts: detention camps, executions, betrayals, and the unhealed wounds of the Emergency.

Nyeri’s history is Kenya’s history compressed into one county — glorious, violent, faithful, rebellious, and forever contested. It is the land of power and of martyrs, a place where the soil is as red as the blood spilled to defend it.