Kisumu’s story begins in the waters of Lake Victoria, but it is not a neat beginning. Like most Kenyan cities, Kisumu is both ancient and recent — a place of barter long before it became a town, and a stage of betrayal long after it became a city. Today, it is remembered as the third capital of Kenya, the stronghold of Luo politics, and the site of state massacres. But to understand Kisumu is to peel back centuries, until the lake was a crossroads of peoples who traded, fought, and displaced one another in rhythms that predate colonial railways or independence flags.

The City of Broken Promises

Kisumu means “the place of barter.” The name itself betrays its origins: a site where communities came not to settle but to meet, trade, and sometimes steal from each other. Grain, cattle, fish, and iron moved across this ground long before the first iron snake of the Uganda Railway hissed into the lakeshore. It was never just a Luo city. It was a shared frontier, a marketplace balanced on the fault lines of migration and conquest.

Before Empire: The Luo and Lake Victoria

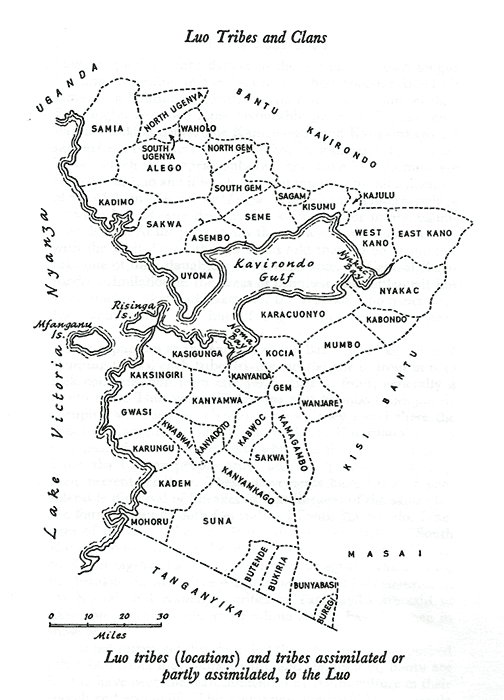

To tell Kisumu’s history, you have to begin with the land known in colonial maps as Kavirondo. It was not empty. By the time the Luo began drifting southwards into the region, the shores of Lake Victoria were already inhabited. Bantu-speaking groups — ancestors of today’s Abaluhya, Gusii, and Kuria — had carved out farmlands, raised cattle, and traded iron tools and grain. Further back, traces of Southern Cushitic groups lingered in oral memory and archaeology, older communities who had once roamed the grasslands before they were swallowed by later migrations.

Then came the Luo migration. Sometime around the 15th century, waves of Luo-speakers moved from the Nile Valley through Uganda into western Kenya. They were armed with cattle, spears, and a social system that absorbed as much as it displaced. Ogot argues that the Luo entry into Kavirondo was not peaceful drift but conquest, a deliberate expansion that pushed some communities out and swallowed others whole. The Gusii were driven into the highlands, where their defensive ridges and stone enclosures still tell of wars against Luo raiders. The Kuria were squeezed southwards. Other groups, less able to resist, were folded into Luo clans through marriage, tribute, or servitude.

By the 18th century, the Luo had become the dominant group along the Kavirondo Gulf. But dominance is not the same as exclusivity. Kisumu’s soil still bore the footprints of multiple peoples, its markets still echoed with many tongues. When the Luo called it Dho Kisumo — the place of barter — they acknowledged that the town was not theirs alone. It was a contact zone, a neutral ground where Luo, Nandi, Abaluhya, and others met to exchange goods under uneasy truces. Trade was both cooperation and confrontation, a fragile peace that could break into raiding at any moment.

This is the paradox at Kisumu’s heart: a city born not as a home but as a meeting point, a crossroads of peoples who bargained, feasted, and sometimes fought. Its name is its history — a reminder that Kisumu began as a place of exchange, not belonging. And in many ways, that would remain its fate: a city always negotiating between peoples, always claimed but never entirely possessed.

The Railway and the Birth of a Colonial Town (1898–1901)

If Kisumu’s first life was as a barter ground, its second was as a railway town. The British did not stumble upon Kisumu; they laid tracks straight into it, dragging empire behind them. By the late 19th century, London had convinced itself that controlling the source of the Nile was a matter of imperial survival. To do that, they needed a railway — from the Indian Ocean at Mombasa, through swamps and escarpments, to the shores of Lake Victoria.

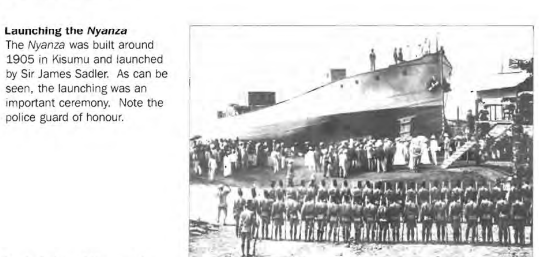

By 1898, the Uganda Railway had crawled past Nairobi and was heading westward. The engineers needed a terminus on the lake, a place where rails could meet steamers, and goods could flow into Uganda. They found Kisumu. Not because it was the only choice, but because it was convenient: a natural bay on the Kavirondo Gulf, already a known trade site, with enough flat land to lay tracks and warehouses.

In 1901, the first train screeched into the lakeshore. The British renamed the place Port Florence, after the wife of the chief railway engineer, George Whitehouse. It was a colonial habit — to overwrite indigenous names with English ones, as if history itself began with their arrival. But the Luo did not stop calling it Kisumu. Barter ground it had been, barter ground it remained.

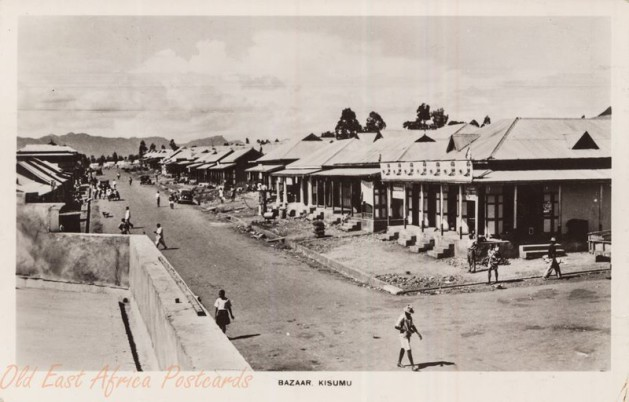

The railway transformed Kisumu overnight. Warehouses rose along the shoreline, steamers docked to ferry goods across the lake, and an entire administrative town sprouted around the station. Indian merchants, many of whom had already come as railway workers, set up dukas and trading firms. European settlers planted themselves in bungalows, their gaze fixed on cotton and commerce. Africans were pushed into segregated quarters, summoned to load cargo by day and expelled back to the margins by night.

Kisumu was no longer just a market; it was an imperial artery. Coffee, cotton, and hides flowed through its port, while rifles, cloth, and bureaucracy flowed in. It was both the end of the railway and the beginning of colonial extraction into Uganda and beyond.

But Kisumu never lost its old name. Port Florence faded quickly, as if even the empire knew it was ridiculous to rename a barter ground after a railway engineer’s wife. Kisumu reclaimed itself. Still, the railway had changed it forever: from a neutral marketplace into a contested town where empire, commerce, and culture collided.

Colonial Kisumu: Segregation and Growth (1900s–1940s)

The railway had planted Kisumu firmly on the colonial map, but it was not a city for everyone. Like Nairobi, Kisumu became a carefully divided settlement, carved up along racial lines. The Europeans claimed the breezy ridges and lakefront bungalows. The Asians, who had first come as railway laborers and traders, were squeezed into commercial districts of dukas and warehouses. Africans — the very people whose land had made Kisumu possible — were herded into “native locations” on the margins, allowed into the town center only as laborers and only on the state’s terms.

This segregation was not just residential. It was economic. Africans supplied the labor — porters, dockworkers, house servants — while Europeans controlled administration and Asians controlled trade. Kisumu’s Africans lived in crowded settlements with poor sanitation, while Europeans toasted their empire at the club and Asians counted coins in their shops. The city grew, but its growth was never equal.

Yet inequality did not breed silence. Kisumu’s dockyards and markets became sites of grumbling, gossip, and eventually agitation. Cotton and fish passed through the port, but so did ideas. By the 1920s and 30s, Luo elites were already petitioning the colonial government for representation. Educated clerks and teachers, products of mission schools, began forming associations that spoke against land alienation, unfair taxation, and racial discrimination.

The colonial state, predictably, dismissed these voices. To the administrators in Kisumu, Africans were labor, not citizens. But the pressure kept mounting. The Luo were not passive bystanders in empire’s town; they were active negotiators, sometimes collaborators, sometimes agitators. Kisumu was not just the end of a railway. It was becoming a political seedbed, a place where questions of justice, land, and equality first took root.

By the 1940s, Kisumu had grown into the most important town in western Kenya. Its port connected Kenya and Uganda, its markets buzzed with goods and gossip, and its inequalities had hardened into daily reality. It was a city divided, but also a city brewing with political potential. The empire thought it had built a railhead. In reality, it had built a powder keg.

Independence and Luo Politics

When independence came in 1963, Nairobi celebrated in Uhuru Park, but Kisumu’s eyes were on Parliament. The Luo had not just participated in the nationalist struggle — they had supplied some of its most vocal leaders. At the center stood Oginga Odinga, the fiery politician from Sakwa, who had risen from teacher and trader to nationalist heavyweight. To many in western Kenya, Odinga embodied Luo pride and the promise that independence would deliver more than just a change of flags.

But independence was already splitting along ethnic and ideological lines. Odinga, a socialist leaning toward the Eastern bloc, wanted a Kenya that redistributed land and wealth. Jomo Kenyatta and his Kikuyu allies leaned toward capitalism and consolidation. In that split, Kisumu found itself cast as the opposition capital, the city of dissent.

The Luo expected independence to bring recognition, development, and inclusion. Instead, they got suspicion. Ministries and parastatals filled with Kikuyu elites; land redistribution was uneven; and Nairobi’s political patronage networks often bypassed Kisumu. The city that had been promised a new dawn felt the old colonial marginalization repainted in black, green, and red.

Odinga broke with Kenyatta in 1966, forming the Kenya People’s Union (KPU). Kisumu became its stronghold. The city’s streets filled with rallies and chants; its residents wore dissent on their sleeves. The KPU was not just a party — it was a rebuke, a declaration that Kenya was not one nation but a fragile coalition, where betrayal could travel faster than trains.

But Nairobi would not tolerate an opposition capital. The state branded Odinga a communist threat, harassed his supporters, and leaned on the police to keep Kisumu in check. The promise of independence — inclusion, dignity, justice — was unraveling into repression. Kisumu, once a railway terminus, had become the terminus of Kenya’s political patience.

The tension would explode in 1969, when Kenyatta visited Kisumu and the city erupted in jeers, accusations, and bullets. But even before the massacre, the betrayal was already written in Kisumu’s story: independence had come, but it had not come for everyone.

The Massacre and Its Shadow

In October 1969, Kisumu became the stage of one of Kenya’s darkest chapters. President Jomo Kenyatta came to open the Russia Hospital, but the city was still raw with grief after Tom Mboya’s assassination and seething with anger over Oginga Odinga’s treatment at the hands of the state. The crowd jeered, the president snapped, and the guns answered. Police and the presidential guard opened fire on civilians. The official death toll was downplayed; survivors insist it ran into the dozens, if not hundreds.

The killings scarred Kisumu permanently. They confirmed what many residents already suspected — that the independence state saw them not as citizens but as enemies. From that day forward, Kisumu was branded Kenya’s rebel city, a place where dissent met bullets and betrayal.

For the full account, read our deep dive: The Kisumu Massacre of 1969: Independence Betrayed.

Kisumu and the Struggles of Democracy (1970s–2000s)

After the 1969 massacre, Kisumu did not retreat into silence. If anything, it dug deeper into defiance. Under Daniel arap Moi’s presidency (1978–2002), the city became a recurring flashpoint — a place the state watched nervously and punished harshly. To Moi, Kisumu was not just opposition turf; it was enemy territory.

In the 1980s, as Kenya slid into a de facto one-party state, Kisumu bore the brunt of repression. Opposition rallies were banned, activists detained, and police patrolled its streets with a heavy hand. Yet whispers of resistance never died. Luo politicians, trade unionists, and student leaders from the University of Nairobi and Maseno fed the city’s political fire. Kisumu’s reputation as the capital of dissent hardened.

The 1990s opened a new chapter. Under pressure from within and abroad, Moi was forced to legalize multiparty politics in 1991. Kisumu erupted in celebration — and in blood. The first rallies of the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD) electrified the lakeside city, drawing crowds that dwarfed anything Nairobi could muster. But state crackdowns followed quickly. Police fired on demonstrators, and teargas became as common in Kisumu as fish in the lake.

Even after Moi fell in 2002, Kisumu’s uneasy relationship with the state persisted. The 2007 general election turned the city into a battleground once again. When Mwai Kibaki was hastily sworn in amid allegations of rigging, Kisumu exploded in anger. Protests filled the streets; shops burned; police responded with live ammunition. The city bled as it had in 1969, a chilling reminder that for Kisumu, democracy often arrived carrying a rifle.

By the 2000s, Kisumu had become both symbol and scapegoat — a city celebrated for its political courage but vilified by the state as perpetually unruly. Every bullet fired in its streets only deepened the conviction that Kisumu’s fight was not just about politics but about recognition, dignity, and justice.

Kisumu Today: Between Lake and Nation

In the 21st century, Kisumu wears two faces. One is modern: a bustling city of over half a million, capital of western Kenya, anchor of devolution, and gateway to Lake Victoria. The port has been revived, linking Kenya again to Uganda and Tanzania. Roads and highways snake into the interior, carrying fish, sugar, and people. Kisumu hosts international conferences, its hotels dot the lakefront, and its skyline has grown from a colonial railhead into a regional hub.

The other face is scarred. The memory of 1969 lingers like smoke; the trauma of 2007 is still visible in bullet wounds and burned shops. Every election cycle, Kisumu braces for violence, as though history insists on replaying itself. The state often treats the city as a test case for riot control, while residents see themselves as the conscience of Kenya — the ones willing to pay in blood to expose betrayal.

And yet Kisumu lives. Its markets buzz, its matatus blast music, its shores feed thousands with Nile perch and tilapia. Culture thrives: benga music, Luo literature, and political satire flourish in ways only a rebellious city can sustain. Kisumu is not just a site of suffering; it is a site of resilience.

Conclusion: Kisumu the Rebel City

Kisumu’s history is the story of a city that has never stopped bargaining — first in fish and grain, later in politics and justice. Born as a barter ground, transformed by the railway, scarred by massacres, and hardened by democracy’s betrayals, Kisumu has always stood at Kenya’s crossroads.

To the state, it is a problem child, forever shouting when told to stay quiet. To its people, it is a badge of honor — the city that refuses to bow, the city that carries memory like a weapon. Nairobi may hold the power, Mombasa the trade routes, but Kisumu holds the conscience.

In Kenya’s story, Kisumu is the rebel capital, the city of broken promises that refuses to stop demanding better. And that refusal, costly as it has been, is what keeps Kisumu alive — a city scarred but unbroken, forever staring back at the nation that betrayed it.