If cities had mirrors, Nakuru’s would be cracked straight down the middle. On one side, pink flamingos flocking in their tens of thousands across the alkaline waters of Lake Nakuru, a paradise scene so delicate it adorns postcards. On the other side, scorched earth, barbed wire, and the ghosts of ethnic clashes that turned fertile ridges into killing fields. Nakuru is both Kenya’s breadbasket and its powder keg, a city where beauty and brutality have always lived uncomfortably side by side.

A City Between Flamingos and Fire

This duality is no accident. Nakuru was built to be a settler capital, the crown jewel of the White Highlands, where colonial aristocrats could sip gin against a backdrop of volcanic soil and wildlife herds. But it was also built on land that had belonged to others — the Maasai, the Kalenjin, the Kikuyu — peoples who grazed, farmed, and fought around Lake Nakuru long before the British laid their tracks. The city’s history is one long negotiation between those who called the Rift Valley home and those who claimed it as real estate.

Before the Settlers: The Rift Valley Frontier

Before the railway and the red roofs of settler bungalows, the valley around Lake Nakuru was a frontier, a contested space between communities who measured wealth not in titles or deeds but in cattle and land. The Maasai, particularly the Laikipiak and Ilpurko sections, roamed these plains with their herds. To them, the Rift Valley lakes were watering grounds, sacred and strategic, part of a vast landscape of pasture and power.

But the Maasai were not alone. The Kalenjin groups — Nandi, Kipsigis, Tugen — pressed into the valley, carving territories along escarpments and river valleys. Their warriors raided cattle, their farmers tilled patches of volcanic soil, and their oral traditions spoke of clashes and truces that shaped the ridges. To the east, Kikuyu migrants expanded into the highlands, clearing forest and planting bananas, maize, and millet. Over centuries, boundaries shifted in cycles of war, marriage, and barter.

Lake Nakuru itself was a magnet. Its shores provided salt licks for livestock, fish for communities, and meeting points for trade. Archaeology suggests that for centuries the Rift Valley around Nakuru was a corridor of exchange, a zone where cultures met and collided. No single group could claim it exclusively; it was a frontier in the truest sense — shared, contested, and constantly shifting.

But the frontier balance was fragile. By the mid-19th century, the Maasai had suffered devastating cattle plagues and internal wars, weakening their hold on the central Rift. The Nandi held firm in the west until the British guns crushed them in 1905. By the dawn of the 20th century, the valley was vulnerable. And just then, the iron snake came hissing in, and with it, settlers who saw none of the old claims, only virgin land waiting for conquest.

The Railway and the Birth of Nakuru Town (1900s)

Nakuru was not born; it was built. In 1901, the Uganda Railway reached the Rift Valley floor, and where the engineers decided to lay a depot, a town materialized almost overnight. The name stuck from the Maasai word En-Akuro — “swamp” or “dusty place,” depending on who you ask. The British saw neither swamp nor dust; they saw paradise.

The land around Nakuru was volcanic, fertile, and blessed with a temperate climate that reminded homesick settlers of the English countryside. To them, this was the heart of what would soon be called the White Highlands — vast estates carved from African land, handed out in title deeds that ignored centuries of occupation. The Maasai had been pushed south after their 1904 and 1911 treaties, stripped of their grazing grounds. The Kalenjin and Kikuyu who farmed the ridges found themselves squeezed into reserves, their ancestral land repurposed for wheat, coffee, and dairy.

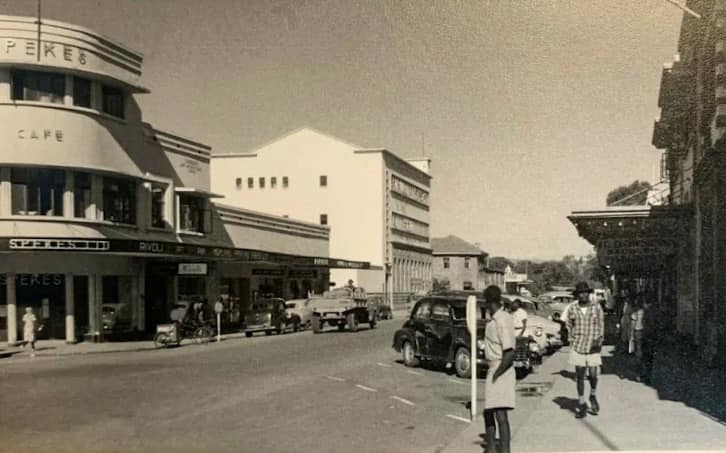

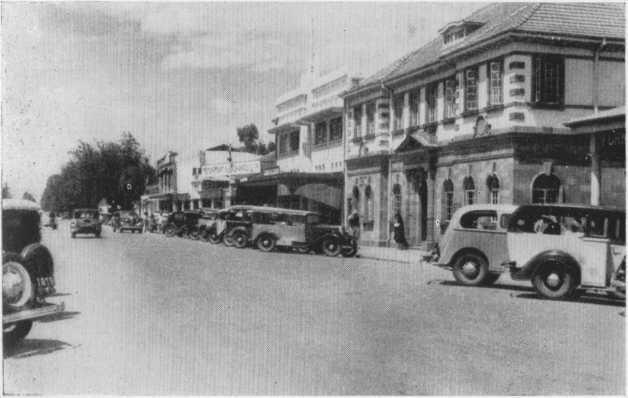

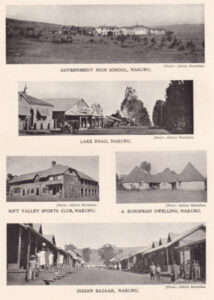

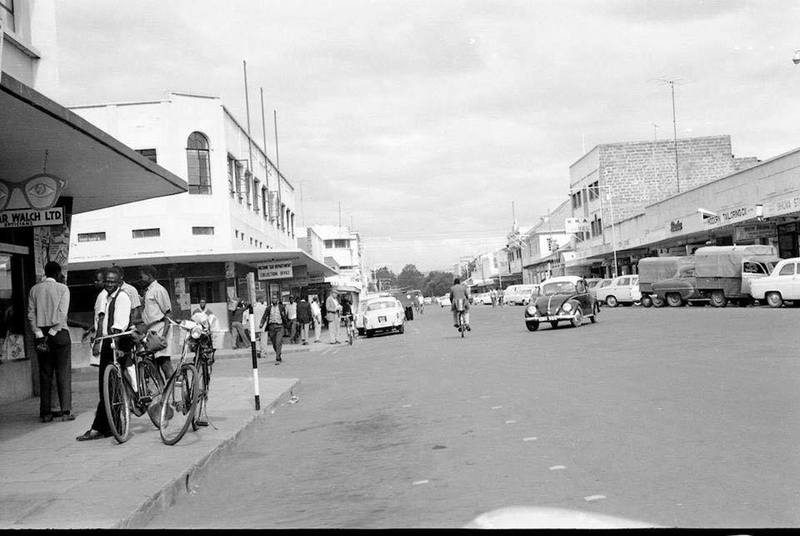

Nakuru town began as a railway stop with corrugated-iron sheds, dusty streets, and a scattering of dukas run by Indian traders who followed the railway westward. But the depot quickly became an administrative hub. Colonial officers built bungalows and clubs; missionaries built churches and schools. By the 1910s, Nakuru had a courthouse, barracks, and a thriving settler community that called it the capital of the highlands.

The railway did more than bring settlers. It tied Nakuru to empire. Wheat from the Rift, hides from Maasai herds, and coffee from Kikuyu farms all flowed through its warehouses toward Mombasa. In return came rifles, gin, and bureaucrats. Nakuru was both a farm town and a funnel, a place where empire turned African soil into global profit.

But beneath the neat streets and settler verandahs, resentment simmered. Africans were already asking the obvious: whose town was this? Whose land had fed this railway? Nakuru’s foundations were steel and stone, yes, but they were also displacement and dispossession. That tension would never leave the Rift Valley.

Nakuru as Capital of the White Highlands (1900s–1940s)

By the 1920s, Nakuru was no longer just a railway depot. It was the beating heart of the White Highlands, the settler paradise that the British carved out of Rift Valley soil. If Nairobi was the colonial capital, Nakuru was its country club — a place where empire came to hunt, to farm, and to indulge.

The settlers boasted of their paradise. Rolling wheat fields spread across former Maasai grazing land; coffee and tea estates sprouted where Kikuyu homesteads had once stood. Ranches fattened cattle for export, while the Rift Valley’s volcanic soil made Nakuru the breadbasket of Kenya Colony. The settler aristocracy held sway here, and they lived like minor royals: sprawling bungalows, weekend polo matches, gin-soaked evenings at the Nakuru Club.

Nearby Naivasha and Gilgil spawned the infamous Happy Valley set — European aristocrats and fortune-seekers who turned the highlands into a stage for scandal. Cocaine, opium, affairs, and duels spilled over from Naivasha’s mansions into Nakuru’s bars and hunting lodges. To the outside world, this was a white man’s Eden in Africa; to Africans, it was theft dressed as glamour.

Nakuru town reflected the hierarchy. The European quarter was leafy and spacious, with wide avenues and red-tiled roofs. The Indian community, descended from railway workers and merchants, clustered in commercial districts, running shops, wholesale trade, and small industries. Africans were pushed into “native locations” — overcrowded, underserviced, and policed by curfews. The geography of Nakuru was the geography of segregation: who lived where, who worked where, who was allowed in the town center after dark.

Yet even in this gilded enclave, cracks appeared. Africans supplied the labor that kept the estates running — tenant farmers, squatters, herders, dockworkers at the railhead. They saw the contrast every day: their own poverty set against the settlers’ opulence. Mission schools in the region, while meant to instill obedience, also produced an educated African elite who began to question why the White Highlands were white at all.

By the 1930s, Nakuru was both the crown jewel of settler Kenya and the seedbed of African grievance. It was a town where flamingos massed in the lake and Europeans toasted empire, but also where dispossessed Africans whispered about stolen land and the need for justice. The stage was being set for confrontation, and the Rift Valley would not remain a playground forever.

Resistance and Nationalism

The British thought they had built permanence in Nakuru — wheat fields stretching to the horizon, settler bungalows shaded by jacarandas, a railway that tied the Rift Valley to the sea. What they had really built was resentment. By the 1940s, Nakuru was simmering with grievances that would soon explode into the nationalist struggle.

Land was the first grievance, and the deepest. Tens of thousands of Africans had been displaced to make room for settler farms. Kikuyu squatters, who once grazed cattle and grew food on these ridges, were reduced to tenants on land that had belonged to their grandparents. They were allowed small plots in return for labor on the estates, a system that bred both dependency and bitterness. The Kalenjin, too, watched as their grazing lands shrank. Even Maasai memories of displacement still burned — treaties and promises broken by the stroke of colonial pens.

Labor was the second grievance. Africans in Nakuru were taxed into working. Hut taxes, poll taxes, and the looming threat of eviction forced men into settler fields and women into domestic service. Their pay was meager; their working conditions harsh. The railway yard, the lifeblood of Nakuru, became a site of both exploitation and organization, where African workers traded stories of injustice and began to imagine something else.

Politics soon followed. Educated Africans from mission schools began forming associations and unions, writing petitions, and joining the growing nationalist wave that swept across Kenya in the 1940s. Nakuru was not Nairobi, but it had its own share of fiery voices, from squatters resisting eviction to teachers and clerks demanding equality.

By the early 1950s, the Rift Valley’s grievances converged into open rebellion. The Mau Mau uprising was rooted in Kikuyu land hunger, and in Nakuru, that hunger was raw. Squatters on settler farms swore oaths, fighters vanished into the forests of the Aberdares and Mau, and the colonial state turned the Rift Valley into a war zone.

Nakuru became both frontline and prison. Detention camps and barbed-wire villages sprang up around the district. Families were herded into “protected villages,” their freedom restricted, their sons hunted as terrorists. The town that had once been the capital of the White Highlands was now the center of colonial counterinsurgency.

Yet repression could not erase the truth. Every eviction, every forced labor contract, every bullet fired in the name of empire only confirmed the settlers’ lie: that Nakuru was theirs by right. By the time the guns fell silent in 1960, the highlands were forever changed. Nakuru’s flamingos still painted the lake pink, but its ridges had soaked up too much blood to remain just a settler’s playground.

Post-Independence Nakuru: Politics and Land

When the Union Jack came down in 1963, Nakuru’s future looked like it might finally return to its rightful owners. The settlers were leaving, their farms sold off, their clubs shuttered. Africans who had been pushed into reserves or shackled as squatters believed independence would mean restitution — land to till, homes to reclaim, justice at last.

But independence did not wipe the slate clean. Instead of going back to the dispossessed, much of the prime land around Nakuru went to the politically connected. Former settler estates were snapped up by ministers, parastatal bosses, and cooperative land-buying companies often led by Kikuyu elites. The promises of Uhuru turned into a new hierarchy of ownership. To many in Nakuru, colonial dispossession had simply been painted in African colors.

The Rift Valley soon became a political chessboard. Jomo Kenyatta’s government encouraged Kikuyu resettlement in Nakuru and neighboring districts, securing both land for loyalists and votes for the ruling party. For Kalenjin and Maasai communities, this felt like a second dispossession, this time not by Europeans but by fellow Africans backed by the state. The seeds of resentment were sown deep into the soil.

Nakuru town itself became a symbol of power. Kenyatta held cabinet meetings at State House Nakuru, using the city as his retreat and stage for consolidating control. Daniel arap Moi, who succeeded him, also made Nakuru central to his rule — it was, after all, in his Kalenjin backyard, though its politics were always complicated by Kikuyu settlement. By the 1980s, Nakuru had become both a presidential playground and a contested frontier of land and identity.

Land-buying companies that had once seemed like vehicles for justice became flashpoints of inequality. Those who could pay into them got titles; those who couldn’t remained squatters, waiting for promises that never materialized. Boundaries blurred, tensions simmered, and the Rift Valley’s history of contested ownership was reborn in new forms.

In the decades after independence, Nakuru was both Kenya’s breadbasket and its tinderbox. The wheat, milk, and tea that fed the nation came from its farms, but so did the grievances that would explode in violence every election cycle. Independence had come, but for Nakuru, the ghosts of land still walked the ridges.

Nakuru and Violence (1990s–2000s)

By the 1990s, Nakuru had become the poster child for Kenya’s broken land question. The Rift Valley was a mosaic of peoples — Kikuyu settlers from land-buying schemes, Kalenjin and Maasai communities claiming ancestral rights, and migrants from across the country drawn by farms and jobs. It was also the playground of presidents. Kenyatta and Moi both treated State House Nakuru as their backyard, but beneath the presidential comfort, the ridges were restless.

The return of multiparty politics in 1991 cracked the Rift open. Moi’s KANU regime, desperate to cling to power, fanned ethnic tensions as both shield and sword. In Nakuru and its environs, violence erupted. 1992 and 1997 saw clashes where homes were torched, families displaced, and entire villages redrawn by fire. The euphemism was “ethnic clashes.” The reality was organized violence — militias, politicians, and state complicity ensuring that land and votes moved in tandem.

Nakuru town itself became a refuge and a pressure cooker. Thousands of displaced families streamed into its estates and camps, carrying stories of neighbors turned enemies overnight. Politicians stood on podiums preaching unity while quietly arming their supporters. The Rift Valley’s soil, so fertile for wheat, had become fertile for fear.

Then came 2007–2008, the breaking point. When Mwai Kibaki was declared president amid allegations of rigged elections, Nakuru exploded. What had simmered in 1992 and 1997 now boiled over. Gangs roamed estates, machetes flashed, and houses burned. The violence that gripped Kenya after the election made Nakuru one of its epicenters, with hundreds killed and tens of thousands displaced. The irony was cruel: a city built as the jewel of the White Highlands was now infamous as a battlefield of Kenya’s democracy.

By the time the peace deal was signed in 2008, Nakuru’s scars were deep. The violence had redrawn lives, neighborhoods, and trust itself. To outsiders, it was another tragic cycle in Rift Valley politics. To those who lived it, it was proof that independence had failed to solve the land hunger and ethnic suspicion planted a century earlier.

Nakuru Today

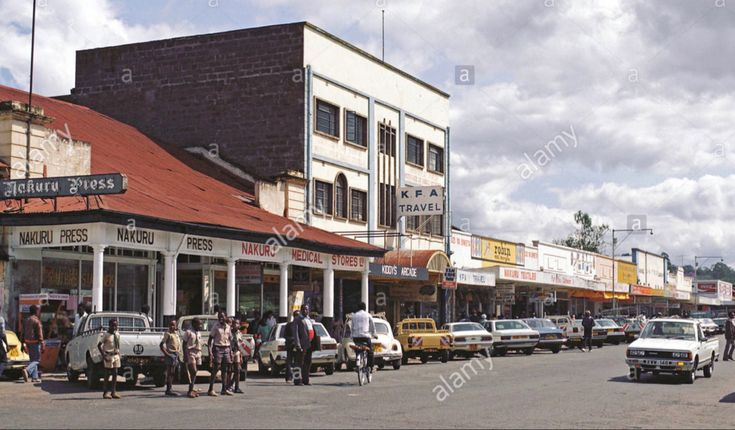

In 2021, Nakuru was officially declared Kenya’s fourth city, a recognition of what it had long been: a hub of commerce, agriculture, and politics at the heart of the Rift Valley. The city bustles with matatus, wholesale markets, universities, and industries. Its farms still feed the nation, its dairy trucks still supply Nairobi, and its highways tie together western Kenya and the capital.

Tourism sells the softer side of Nakuru: Lake Nakuru National Park, its flamingos painting the water pink, its rhinos lumbering through acacia thickets, its Menengai Crater drawing hikers and pilgrims. From a distance, Nakuru looks like a place blessed twice over: with fertile soil and natural wonders.

But the ghosts are never far. Families still live as squatters on the edges of old estates, waiting for titles that never come. The scars of the 1990s and 2007 linger in memories and in the patchwork of neighborhoods where trust can be fragile. For many residents, city status is a badge of pride, but also a reminder of how uneven development has been: new malls rising while informal settlements sprawl in their shadows.

Nakuru today carries itself as both a modern city and a historical crossroads — proud of its flamingos, wary of its fire.

Conclusion: The Rift’s Mirror

Nakuru is not just another town in Kenya. It is a mirror, reflecting the contradictions that run through the country itself. It was the jewel of the White Highlands, built on land taken from Maasai, Kalenjin, and Kikuyu communities. It was the breadbasket of empire and later of the republic. It was a playground for settler aristocrats, and later a hunting ground for political militias. It has been a site of flamingo migrations and forced displacements, of State House retreats and refugee camps.

To walk its streets is to see Kenya in microcosm: natural beauty yoked to political betrayal, abundance tied to dispossession, unity undermined by ethnic suspicion. Nakuru’s history is not just about flamingos and farms. It is about how a city can be both paradise and battlefield at once.

The lake glitters pink, the wheat sways golden, but beneath the ridges lie the stories of conquest, rebellion, and survival. Nakuru is the Rift’s mirror — cracked, beautiful, and impossible to look away from