On October 8, 2004, in Oslo, a woman from the ridges of Nyeri walked onto a stage and made history. The Nobel Committee awarded Wangari Maathai the Peace Prize, the first African woman to win it, for “her contribution to sustainable development, democracy and peace.” The world saw an environmentalist. Kenyans knew her as something more: a scientist, a dissenter, a woman who planted trees as weapons against dictatorship.

Her journey was not neat. She was beaten, divorced, jailed, and ridiculed. But she refused to bow. She faced down presidents and policemen with seedlings in her hands, insisting that the fight for justice could begin with something as small, as stubborn, as a tree.

Roots in Nyeri

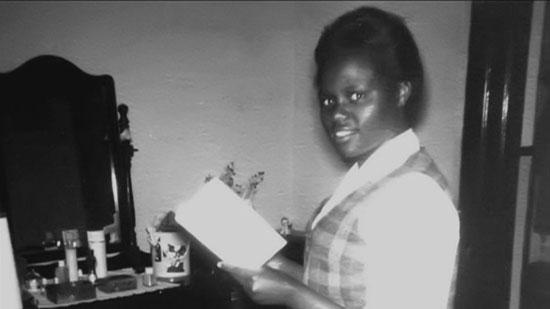

Wangari Muta Maathai was born in 1940 in Ihithe village, Nyeri, when Kenya was still under colonial rule. Her childhood was marked by streams, forests, and farms. She learned early the rhythms of soil and water, how trees held hillsides together and shaded crops. In the reserves of central Kenya, land was crowded and life was hard, but the natural world still gave.

She excelled at school, a rare path for girls in her generation. Mission teachers recognized her brilliance, and she became one of the beneficiaries of the Kennedy Airlift of 1960, which sent hundreds of young East Africans to study in the United States. For Wangari, this opened a door to a wider world — Mount St. Scholastica College in Kansas, then the University of Pittsburgh. She studied biology, a discipline dominated by men, and graduated with honors.

Returning to East Africa in the late 1960s, she earned a PhD in veterinary anatomy at the University of Nairobi, becoming the first woman in East and Central Africa to hold a doctorate. It was a milestone, but also a beginning. She had tasted possibility, and she would not be content with polite ceilings.

Planting the Seeds of Activism

As a lecturer at the university, Wangari faced the thick walls of patriarchy. Male colleagues dismissed her, and when she sought promotions, she was sidelined. Her marriage to Mwangi Maathai, a rising politician, collapsed amid accusations that she was “too educated, too strong, too hard to control.” The divorce was public and brutal. At one point, a judge declared she was “too difficult a woman.” She replied, famously: “The judge is either incompetent or corrupt.” For that, she was jailed for contempt of court.

But hardship fed her fire. She saw how women bore the brunt of poverty — fetching water from drying rivers, searching miles for firewood, watching topsoil wash away. To her, ecology was not abstract science. It was women’s daily survival. And she began to imagine a movement where women could heal both the land and themselves.

The Green Belt Movement

In 1977, Wangari founded the Green Belt Movement. The idea was deceptively simple: pay women small stipends to plant trees. Each tree was a strike against deforestation, soil erosion, and hunger. But the trees were also politics: proof that ordinary women could take control of their environment when the state would not.

Seedlings spread like whispers across villages. Soon tens of thousands of women were planting, nurturing, and protecting trees. By the 1980s, the movement had planted millions. It was environmental work, but also civic education. In community meetings, women spoke about land, corruption, and rights. The seedlings became a language of resistance.

Defiance in the Park

The Moi years turned Wangari into a national irritant for the regime. In 1989, she led protests to stop a skyscraper complex in Uhuru Park, Nairobi’s central green lung. The plan was grandiose: a $200 million complex with a statue of Moi at its center. Wangari denounced it as theft of public land. The state mocked her, called her a crazy woman, and tried to silence her. The project collapsed under international pressure. Uhuru Park was saved.

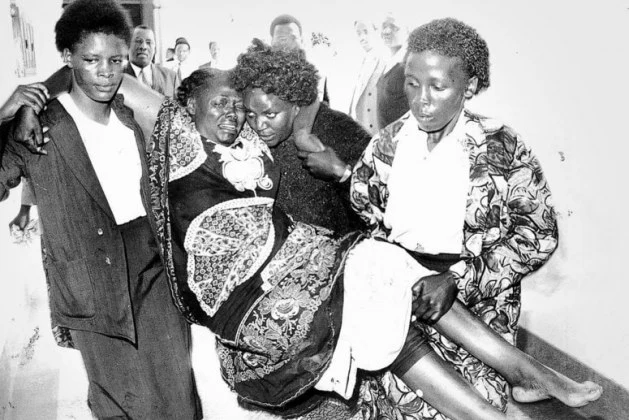

A decade later, she confronted another assault: land-grabbing in Karura Forest, a fragile woodland in Nairobi. Developers armed with title deeds moved in to clear trees. Wangari and her supporters marched to the forest, carrying seedlings. Police descended with batons and tear gas. She was beaten unconscious, but not broken. Images of her bloodied but unbowed spread worldwide. Karura was saved too.

These confrontations made her a hero to the public and a thorn in the regime’s side. Moi sneered that she was “a mad woman who has inherited her father’s genes.” She responded by planting more trees.

A Global Voice

By the 1990s, Wangari’s defiance had won her admirers far beyond Kenya. International organizations awarded her prizes for environmental work and human rights. She spoke at UN conferences, framing ecology not as luxury but as survival — especially for Africa. She insisted that democracy and sustainability were inseparable: corrupt regimes destroyed forests as easily as they destroyed freedoms.

The Nobel Peace Prize in 2004 was the culmination of decades of planting, protesting, and refusing to yield. For the committee, she was proof that peace could grow from the soil. For Kenyans, it was vindication: the madwoman of Karura was the conscience of a nation.

Legacy and Passing

Even after her Nobel, Wangari remained restless. She served briefly as an assistant minister in Mwai Kibaki’s government, but politics was never her natural home. She was too blunt, too unwilling to compromise. She preferred trees to backroom deals.

When she died of cancer in 2011, Kenya mourned not just a woman but an era. The Green Belt Movement had planted over 50 million trees. More than that, she had planted a new way of seeing — that the fight for justice could begin with soil and seedlings, and that women could lead revolutions without firing a shot.

Her funeral was a state affair, yet her coffin was made of hyacinth and bamboo, in keeping with her wishes for sustainability. Even in death, she refused excess. She left behind a movement still alive, forests that still breathe, and a challenge that still lingers.

The Roots Remain

Wangari Maathai was never just a tree planter. She was a disrupter of systems, a woman who understood that planting trees was also planting ideas — about freedom, equality, and dignity. Where the state saw parks as real estate, she saw them as sacred. Where presidents saw forests as profit, she saw them as inheritance.

Her story is Kenya’s story in miniature: land stolen, voices silenced, women dismissed, yet defiance surviving in unexpected forms. She turned seedlings into symbols, parks into battlegrounds, and herself into the conscience of a nation.

Today, in Uhuru Park and Karura Forest, trees sway that would not be there without her. In Nyeri, where she was born, hills are greener because she dreamed of roots. And across the world, environmentalists speak her name as proof that one person can bend history.

The woman who planted trees has gone, but the roots remain.

Read Next

- The History of Nyeri — The ridges, missions, and rebellions that shaped Wangari Maathai’s homeland.

- The Birth and Evolution of Kenya’s Multiparty Democracy — How defiance in parks and streets opened political space for a new Kenya.

- The Evolution of Women’s Participation in Kenyan Politics: A Post-Independence Perspective — From pioneers to powerbrokers, the untold story of Kenyan women in politics.

- Kenya’s White Highlands: Land, Race, and the Economics of Exclusion — The land battles that explain why trees became political.

- The History of Nairobi — A swamp turned capital, and the battleground for Maathai’s fiercest protests.

- Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya, 1952–1960 — The war for land and freedom whose echoes carried into Wangari’s struggle.