In 2003, the cricketing world witnessed an underdog story for the ages. Kenya – a country with no Test status, sparse cricketing infrastructure, and minimal international support – defied all odds to reach the semi-finals of the ICC Cricket World Cup. It was a run filled with drama, disbelief, and immense national pride. By toppling established teams and becoming the only non-Test-playing nation ever to make a World Cup semi-final, Kenya’s 2003 campaign stands as a beacon of hope for every underdog. This is the story of how a collection of enthusiastic amateurs and unsung talents from Nairobi shocked the cricketing elite and why that magical moment remains both inspiring and bittersweet.

Background: From Qualifiers to the World Stage

Kenya’s road to the 2003 World Cup began long before the tournament itself. As an Associate member of the ICC, Kenya had gained One Day International (ODI) status in 1996 after a strong showing in the ICC Trophy (the qualifying tournament for non-Test nations). They had made their World Cup debut in 1996, instantly making headlines with a stunning upset of the West Indies – bowling out the former champions for 93 in a shocking victory. That famous 1996 win put Kenya on the cricket map and saw the emergence of players like Steve Tikolo, Maurice Odumbe, and Thomas Odoyo, who would become pillars of the team.

However, Kenya’s progress was not linear. In the 1999 World Cup, the team lost all their matches, exposing the gap in experience and resources compared to full-member nations. Internal turmoil in Kenyan cricket administration and lack of funding also hampered development – by 1999, captain Aasif Karim retired amid board conflicts and poor results. Still, the core of talented players remained, and with the appointment of former India batsman Sandeep Patil as coach, Kenya prepared rigorously for 2003. In the lead-up, they even managed an ODI win against India in a triangular series, signaling that they could trouble bigger teams on their day.

Being named one of the co-hosts of the 2003 World Cup (along with South Africa and Zimbabwe) meant Kenya qualified automatically for the tournament. Few experts gave them any chance in a pool that included heavyweights like South Africa, Sri Lanka, West Indies, New Zealand, plus fellow minnows Bangladesh and Canada. At the time, no non-Test team had ever gone beyond the first round of a World Cup. For Kenya, just winning a couple of games would have been considered a success – no one imagined they would progress further, let alone make the final four.

The Team and Its Heroes

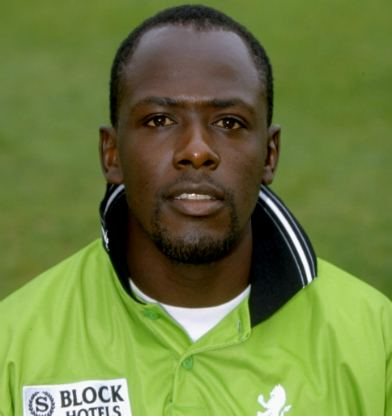

Kenya’s 2003 squad was a mix of veterans and young talents, united by belief in their coach and in each other. Leading them was Steve Tikolo, a batting all-rounder widely regarded as Kenya’s finest cricketer. Tikolo had been part of every World Cup since 1996 and in 2003 he was at his peak – as captain he “topped both the batting and bowling averages” for Kenya in the tournament, scoring more runs than any two teammates combined. A stylish middle-order batsman and handy off-spinner, Tikolo’s experience and calm leadership were the backbone of the team.

Another senior figure was Maurice Odumbe, an explosive all-rounder and one of the first Kenyan superstars. Odumbe had captained Kenya in the 1996 World Cup and was known for his charismatic stroke-play and useful slow bowling. He was a big-game player – for instance, he had top-scored with 83 in a 1999 World Cup match against Sri Lanka and earned Man of the Match even in defeat. In 2003, Odumbe’s verve shone in key moments, including a dashing 38 off 20 balls against Zimbabwe that helped clinch Kenya’s semi-final spot. His confidence was infectious; as Kenya kept winning, Odumbe famously proclaimed, “They said we should not be in the Super Six. They said we should not be in the semi-finals. The next thing they’ll say is we should not be in the final”, reflecting the team’s defiant self-belief.

Supporting Tikolo and Odumbe was a talented cast. Thomas Odoyo, a quietly effective seam-bowling all-rounder, often gave Kenya vital breakthroughs. Odoyo was Man of the Match against Canada, taking 4/28 and scoring crucial runs in a tense chase. Kennedy Otieno (also known as Kennedy Obuya), the team’s wicketkeeper-opener, provided stability at the top. He hit a composed 79 against India’s world-class bowlers in the Super Six round, showing that Kenyan batsmen could occupy the crease against top teams. Kennedy’s role behind the stumps was also notable – he would finish the tournament with 10 dismissals, the fourth-most by any keeper in 2003.

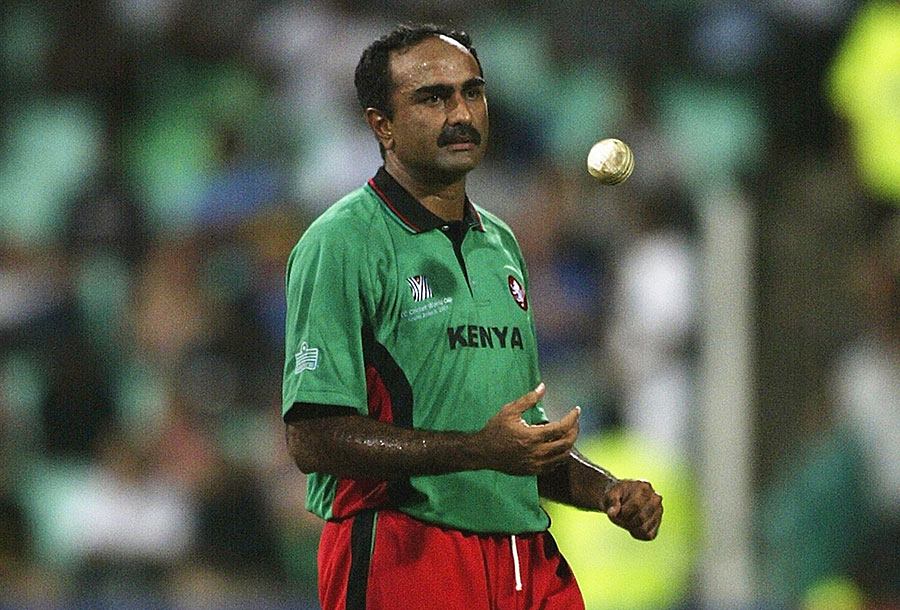

Then there was Collins Obuya, the breakout star and symbol of Kenya’s youth. Only 21 during the World Cup, Collins Obuya was a leg-spinner with a shy demeanor – yet on the field he displayed a fearless flair. Remarkably, he had honed his bowling by watching tapes of Pakistani great Mushtaq Ahmed and had only a handful of ODI wickets to his name before the World Cup. In 2003, Obuya became Kenya’s unlikely match-winner in its biggest upset (more on that shortly), ending with 13 wickets in the tournament – among the top bowlers overall. His performance proved that even without a professional structure, raw talent from Nairobi’s backyards could rise to global standards.

Completing the core was Aasif Karim, a 39-year-old former captain coaxed out of retirement for one last hurrah. Karim was a left-arm spinner who hadn’t played international cricket since 1999, but he answered the call when Kenya needed experience. His presence would prove invaluable in the pressure moments of the Super Six stage, where he delivered one of World Cup’s most extraordinary bowling spells. Together with others like opening batsman Ravindu Shah, paceman Martin Suji, and spinner Jimmy Kamande, the team was greater than the sum of its parts. Coach Sandeep Patil instilled fitness and discipline, but also encouraged the players to “fight for it” with a simple belief – the kind Kenyans were used to seeing from their Olympic runners.

With this mix of seasoned campaigners and hungry youngsters, Kenya entered the World Cup dreaming of an unlikely spot in the second round. What followed would surpass their wildest dreams.

Group Stage: Shocks, Upsets, and a Nation Awakening

Kenya’s World Cup campaign began unremarkably but gathered momentum like a rolling snowball. In their opening group match on February 12, 2003, Kenya faced co-hosts South Africa, a top title contender. As expected, South Africa dominated – Kenya were skittled for 140, and the Proteas raced to a 10-wicket win. It was a harsh reality check, but there was no shame in losing to such a powerful side. The team remained upbeat, knowing their real battle would be against the lesser-ranked teams ahead.

The first glimpse of Kenyan resilience came in their next match, against fellow minnows Canada. Here was a must-win game if Kenya hoped to register any success. Canada posted 197, a competitive total thanks to a century by their batsman John Davison (who had notably hit the fastest World Cup hundred earlier in the tournament). Kenya’s chase wobbled, but Ravindu Shah anchored with 61 and Thomas Odoyo’s all-round heroics (4 wickets and a steady 27* with the bat) saw Kenya scrape home by 4 wickets. It was Kenya’s first World Cup victory since 1996, and it infused the side with confidence.

Next came a bizarre twist of fate that would become a big talking point: Kenya’s fixture against New Zealand in Nairobi. Citing security concerns in Kenya (after a 2002 bombing in Mombasa), the New Zealand cricket board had decided not to send their team for this match. As a result, Kenya was awarded a win by forfeit (walkover). The free points catapulted Kenya up the group standings, but also drew skepticism from some corners – critics argued Kenya had gained an unfair advantage towards qualification. The Kenyan players, however, took offense at the implication they didn’t deserve to progress. “We beat Test teams, and that was something incredible,” coach Patil later emphasized, pointing out that Kenya won the games that mattered. Indeed, whatever fortune the New Zealand default gave, Kenya soon proved they belonged by earning victories on merit.

On February 24, 2003, at the Gymkhana Club Ground in Nairobi, Kenya achieved the “giant-killing” moment that stunned the world. Facing Sri Lanka, the 1996 World Cup champions, Kenya pulled off one of the greatest upsets in cricket history. Batting first on a dusty home pitch, Kenya scrapped their way to 210/9 in 50 overs – opener Kennedy Otieno led with 60, and Tikolo and Odumbe chipped in handy runs. It seemed a modest total against Sri Lanka’s formidable batting lineup, which included stars like Sanath Jayasuriya, Aravinda de Silva, and Mahela Jayawardene. But a young Kenyan leg-spinner had other ideas. Collins Obuya produced a mesmerising spell of 5 wickets for 24 runs, ripping through the Sri Lankan middle order. One by one, Sri Lanka’s seasoned batsmen fell to the wiry 21-year-old’s googlies and leg-breaks – Obuya removed de Silva, Kumar Sangakkara, and Jayawardene, among others. Sri Lanka collapsed for 157, and Kenya triumphed by 53 runs, sending shockwaves through the tournament.

As the Kenyan team celebrated on the field amid joyous home fans, disbelief rippled across the cricket world. No one expected the “minnows” to beat a South Asian powerhouse. The victory proved Kenya’s earlier gains were no fluke – they could outplay a top side through skill and spirit. Interestingly, back in Nairobi that night, the players discovered just how unexpected their feat was locally. They went to a popular bar to celebrate, only to find that most patrons hardly recognized them. “No one will even buy us a drink… I guess no one’s bothered,” Maurice Odumbe quipped, noting that cricket was still obscure to the Kenyan public at large. With only a few thousand active cricket players in the country (mostly from the small Asian-Kenyan community), many ordinary Kenyans didn’t yet realize the magnitude of what had happened. But that was about to change as the team’s Cinderella run continued.

Returning to South Africa for the remaining group games, Kenya next faced Bangladesh – ironically a Test-playing nation, but the weakest of the full members. Here Kenya asserted their superiority, winning comfortably by 32 runs. That win, coming on March 1 in Johannesburg, effectively sealed Kenya’s place in the next round. Even though Kenya lost their final group match against the West Indies, it mattered little. By then, an extraordinary situation had unfolded in Group B: the mighty South Africans had been eliminated (after a rain-affected tie in a match they needed to win), and Kenya topped the group standings alongside Sri Lanka. With 4 wins (including the NZ forfeit) and 2 losses, Kenya finished ahead of established teams. They had made history by becoming the first non-Test nation to reach the World Cup’s second phase (Super Six). From being tournament outsiders, Kenya suddenly found themselves as the most successful “giant killers” the World Cup had ever seen.

Back home, the mood began to shift. As one Nairobi newspaper punningly headlined after Kenya’s progression: “Kenya Believe It!”. Curiosity about cricket surged among the public. During the Super Six qualifier against Zimbabwe, local sports bars that started out nearly empty saw crowds of new fans trickling in over the course of the match. Many viewers were unfamiliar with cricket rules – some thought a fallen wicket earned the batting team a point! – yet they cheered every Kenyan success passionately. For perhaps the first time, cricket was making headlines alongside Kenya’s usual sports of interest, and it was unifying people of different backgrounds to rally behind the national team. The sense of national pride swelled with each victory, even as disbelief lingered: was tiny Kenya really among the world’s top six teams?

The Super Six: Continuing the Dream

Entering the Super Six stage, Kenya carried forward the points from their group wins against fellow qualifiers (the format allowed teams to bring results against teams that advanced). This gave Kenya a head start in the round-robin Super Six, where they had to face three new opponents from the other group: India, Zimbabwe, and Australia. It was a tall order – two of those were top-tier teams and former World Cup champions. By now, however, Kenya was playing with house money; they had already exceeded expectations and could approach the big games fearlessly.

Kenya’s first Super Six match on March 7 was against India in Cape Town. The Indian side, led by Sourav Ganguly and Sachin Tendulkar, had found superb form, and they proved too strong for Kenya that day. Kenya posted a respectable 225/6, with Kennedy Otieno impressing through his 79-run knock against India’s famed bowling. But Ganguly’s century took the game away, and India won by 6 wickets. Despite the loss, Kenya earned praise for giving India a decent fight, and it was clear they weren’t simply content to be there – they were still competing hard.

The defining match of the Super Six for Kenya came against Zimbabwe on March 12 in Bloemfontein. This was effectively a knockout game – the winner would likely secure a semi-final spot. Zimbabwe, though a Test nation, were in turmoil during the 2003 World Cup (with internal issues and the political protest of Andy Flower and Henry Olonga casting a shadow). Kenya sensed an opportunity and seized it brilliantly. In a disciplined bowling effort, Kenya bowled out Zimbabwe for 133, with veteran seamer Martin Suji taking 3/19 and the fielders backing superbly. The chase under pressure could have been tricky, but the ever-reliable Tikolo (making 23) and Odoyo (43*) ensured there were no hiccups. Kenya romped to victory by 7 wickets in just 26 overs – an emphatic result that clinched their place in the World Cup semi-finals. It was an almost surreal achievement: Kenya had not only outperformed another Full Member team, but they had officially secured a top-four finish in the World Cup. As one South African daily marveled, “Kenya believe it!” indeed.

The win over Zimbabwe sparked celebrations, but also some controversy. Kenya and New Zealand were now tied on Super Six points vying for the last semi-final berth. By the tournament rules, the tie was broken by carried-forward points (points gained against other Super Six qualifiers in the group stage). Thanks to Kenya’s famous win over Sri Lanka (who had advanced) and the fact that New Zealand’s forfeit had given Kenya full points in their group meeting, Kenya edged out New Zealand for the semi-final spot. New Zealand were left to rue their decision not to play in Nairobi – their caution had literally cost them a chance at the trophy. For Kenya, it was vindication: they had beaten Sri Lanka and Zimbabwe outright, and no one could say they hadn’t earned their semi-final place. As coach Patil reflected, reaching even the Super Six had been beyond dreams, but reaching the semis was “something incredible” achieved by defeating multiple Test teams.

Kenya’s final Super Six game came against the unbeaten Australia on March 15 in Durban. Australia were the defending champions and steamrolling every opponent, so when they batted first and blasted to 109/2 in just 15 overs, it looked like Kenya might be on the receiving end of a rout. But what followed was one of the tournament’s most captivating passages of play. Aasif Karim, with all his guile and experience, bowled a spell for the ages. In 8.2 overs of crafty left-arm spin, the 39-year-old delivered 6 maiden overs and took 3 wickets for just 7 runs. Under the Durban lights, Karim bamboozled the likes of Ricky Ponting (caught off a miscued stroke) and crucially dismissed Darren Lehmann and Brad Hogg in quick succession. For a brief moment, the mighty Australians were wobbling, slipping from 109/2 to 117/5, and Kenyan hopes soared. Australia ultimately recovered to win by 5 wickets, but not before Karim’s magical spell had given them a real scare. His bowling analysis – 8.2–6–7–3 – was one of the most economical in World Cup history, and it earned him a standing ovation as he left the field. Even in defeat, Kenya had proven their mettle once more, fighting the world’s best with all their heart.

By the end of the Super Six, Kenya had amassed 14 points, finishing third behind only Australia and India, and ahead of cricket giants like Sri Lanka. It was an astounding outcome that captured imaginations worldwide. Back home in Kenya, cricket – once considered a sport only for the Asian and white minority – was finally penetrating the national consciousness. People from Nairobi to small towns tuned in to radio and TV for Kenya’s next match, and even those who didn’t fully understand the rules understood that their compatriots had made them proud on the global stage. As the semi-finals approached, Kenyan fans dared to dream the impossible dream.

The Semi-Final: A Date with India

On March 20, 2003, Kenya walked out onto the field at Kingsmead, Durban, to play a World Cup semi-final against India. It was a moment of sheer pride and high emotion – the Kenyan team lining up for the national anthem alongside a cricket powerhouse, with a place in the final at stake. By now, even the harshest skeptics had to acknowledge that Kenya’s presence was not a fluke or charity; they had earned their spot. Kenyan captain Steve Tikolo summed up the mindset: “Anything can happen on a given day. We can beat them,” he insisted, reflecting the unyielding self-belief in the squad.

For a while, Kenya’s bowlers managed to contain India’s vaunted batting. Under the lights, seamers Peter Ongondo and Martin Suji bowled with discipline. But India’s class soon shone through. Sourav Ganguly, in regal form, struck a commanding century (111), and Sachin Tendulkar added 83, as India piled up 270/4 in their 50 overs. The target of 271 was the highest Kenya would have had to chase in the tournament – a daunting ask against India’s bowling attack which included the fiery Zaheer Khan and crafty veteran Javagal Srinath. Kenya’s batting reply began in the worst way, with the top order crumbling under the pressure of India’s pace. At 28/3, the dream was fading quickly.

Fittingly, it was Steve Tikolo who fought to prolong the resistance. The captain played a brave innings of 56, including some defiant sixes, to salvage Kenyan pride. But the target was never within reach. Under relentless pressure from India’s bowlers, Kenya were bowled out for 179 in 46.2 overs. India won by 91 runs, ending Kenya’s fairytale. As the Indian players shook hands with the Kenyans, and the Durban crowd applauded both sides, Kenya’s campaign came to a close one step shy of the final.

There was disappointment in the Kenyan camp – competitive athletes as they were, they had dared to believe they could go all the way. Yet, overriding the loss was a sense of genuine accomplishment and joy. The Kenyan players embarked on a lap of honour, waving to the crowd and bowing in thanks for the support. They were semi-finalists of the World Cup, an achievement no one could ever take away. In Nairobi and across Kenya, people celebrated this unlikely success. The team had united the country and given sports fans back home a new set of heroes to cherish. As Tikolo later reflected, the 2003 World Cup “was our finest hour” – proof that Kenya could compete with the best on the cricket field if only given the chance.

Cricket pundits worldwide lauded Kenya’s journey. It was the ultimate underdog saga – from being nearly anonymous in world cricket to beating big teams and reaching the semis. The phrase “Kenya shock the cricketing world” became a common refrain. Many hoped this would herald the emergence of a new cricketing nation in Africa, building on the legacy of 2003.

Aftermath: A Triumph and the Troubles That Followed

Kenya’s 2003 World Cup exploits were supposed to be a launchpad for bigger things. There was talk of Kenya being granted Test status – after all, they had performed far better than the ICC’s newest Test team Bangladesh (who hadn’t won a single World Cup game in 2003). The International Cricket Council initially showed interest in fast-tracking Kenya’s development. Kenya even formally appealed for elevation to Test membership that year. However, the aftermath of 2003 turned out to be a sobering tale of opportunities lost.

In the immediate years after the World Cup, Kenyan cricket plunged into chaos due to a combination of internal and external factors. On the governance side, the Kenya Cricket Association (KCA) was beset by politics and mismanagement. A bitter dispute between players and the board erupted by late 2003: players went on strike over unpaid wages and contract disputes, essentially halting the momentum gained from the World Cup. The strikes dragged on for months, prompting government intervention and the eventual ouster of the old cricket administration in 2005. By the time the dust settled, Kenya had lost valuable time and sponsors; international teams were hesitant to schedule matches amid the turmoil. Kenya played almost no official ODIs for 18 months after the World Cup, a fact that infuriated Steve Tikolo and his teammates. “After our World Cup performance we have hardly played any games… If you have one-day status and don’t play any ODIs then the status is as good as useless,” Tikolo lamented in 2004, openly blaming the ICC for leaving Kenya in the cold. Instead of building on success, Kenya faced “virtual international isolation” – a recipe for regression.

The team itself also suffered from body blows. Maurice Odumbe, one of Kenya’s stars, was embroiled in a scandal when he was found guilty of inappropriate contact with an alleged bookmaker. In August 2004, Odumbe was banned from cricket for five years. The ban robbed Kenya of a key player and cast a shadow over the sport’s image at home. Other stalwarts like Asif Karim and Ravindu Shah retired. The golden generation was aging, and without a robust domestic structure, few quality replacements were coming through. Coach Sandeep Patil left his post after the World Cup success (returning to India to coach elsewhere), and subsequent coaching stints were short-lived amid the off-field instability.

Funding that was promised to Kenya often went unused or was mismanaged. Aasif Karim later revealed that while ICC and countries like India and South Africa were initially willing to invest in Kenyan cricket after 2003, “those funds were misappropriated. We lost a golden opportunity to capitalise on all that goodwill and support.”. Instead of establishing the grassroots youth programs and nationwide development needed, the sport remained confined largely to Nairobi’s club circles. As years passed, the lack of a first-class domestic league and an “A” team to groom players led to a decline in playing standards. By 2007, Kenya had not beaten any Test nation again since the Sri Lanka upset, and even began losing regularly to lower-ranked teams they once dominated.

The 2007 World Cup saw Kenya fail to repeat their heroics – they won only against Canada and were eliminated in the first round. In the 2011 World Cup, a number of the 2003 veterans (Tikolo, Odoyo, the Obuya brothers) were still playing, but age had caught up and the team lost all six of its matches. After 2011, Kenya did not qualify for the World Cup again. The ICC, for its part, shrank the World Cup format to 10 teams in 2015 and 2019, making it even harder for Associate nations to get such opportunities. Countries that had been inspired by Kenya – like Ireland and Afghanistan – invested heavily in their cricket and leapfrogged Kenya, eventually attaining Test status themselves. Kenya, unfortunately, became a cautionary tale of how a breakthrough can slip away without infrastructure and sound management.

Insiders cite multiple reasons for this downfall. Player development in Kenya stagnated: as Karim noted, the country always had a small player pool and lacked a strong pipeline to replace the golden generation. Cricket never quite broke out of its niche; despite the 2003 euphoria, it struggled to compete with football, rugby, and athletics in a nation where those sports dominate popularity. Without regular competition against top teams (something Tikolo had pleaded for), the team’s skills went backward. By 2008, a local journalist grimly described Kenyan cricket as “on its deathbed,” citing chronic funding shortages and administrative failures to implement development programs. The same article scolded cricket officials for failing to build on “the huge image that Kenya cricket had built in 2003”.

In short, politics and internal rifts in the Kenyan board, coupled with ICC’s lukewarm support and the absence of a sustained grassroots plan, derailed what might have been Kenya’s rise as a new cricketing power. As Aasif Karim put it bluntly, “We lost our way after 2003.” The golden generation gradually retired: Tikolo played on as long as he could and later went into coaching; Odoyo too transitioned to coaching; players like Odumbe and others faded from the scene. Collins Obuya remained one of the few continuous threads – he reinvented himself as a batsman and continued to play into the 2010s, even captaining Kenya at one pointi. But the team never came close to reaching those World Cup heights again. By 2014, Kenya had even lost its ODI status after poor performances, a far cry from the semi-finalists of 2003.

Legacy and Reflection: Can the Magic Be Revived?

For Kenya, the 2003 World Cup was a moment of unifying joy and proof of potential. It inspired a generation of young Kenyan players and fans. The sight of Steve Tikolo leading the team on a lap of honour after the semi-final – Kenyan flag draped on his shoulders, waving to a crowd that included many African fans who had adopted Kenya as “their team” – remains iconic. In that moment, cricket in Kenya felt like it had transformed from a minority pastime to a sport capable of capturing the nation’s imagination. Schools in Nairobi reportedly saw increased interest in cricket clubs right after the World Cup. The players became national celebrities, at least for a time; some were even honored by the government on returning home.

Yet the poignant question lingers: can that 2003 magic ever be revived for Kenya? Two decades later, many of the structural issues still persist. There have been efforts – for instance, a new Cricket Kenya board and development programs, occasional wins in lower-tier competitions, and plans for a T20 league to spark fresh interest. However, even Kenyan cricket legends acknowledge that a lot of rebuilding must happen from the ground up. “We need competent administration… and a sustainable programme,” urged Karim, emphasizing that relying on a once-in-a-generation batch of players isn’t enough. The sport needs nurturing at the grassroots, better facilities, and consistent competition to flourish again.

For now, Kenya’s 2003 World Cup run remains a treasured memory – not only for Kenya but for cricket lovers worldwide who root for the underdog. It stands as a testament to what passion and self-belief can achieve against the odds. It’s the story of Tikolo’s cover drives and fighting spirit, Odumbe’s swagger and guts, Odoyo’s all-round grit, Obuya’s dream spell bewildering giants, and Karim’s late-career masterpiece nearly toppling the best team in the world. It’s the story of a team that united a nation – however briefly – in collective pride.

No matter how far Kenyan cricket has fallen since, the legacy of 2003 endures. It whispers to every Associate nation that on the right day, with the right team, anything is possible. As cricket fans, we can only hope that one day Kenya (or another underdog) will rise again to script a saga as stirring as the Kenyan fairytale of 2003. Until then, that World Cup semi-final finish remains an indelible chapter in cricket history – a reminder that even the smallest cricketing David can topple Goliaths and send a country into raptures.

Sources

- Kenya’s historic 2003 World Cup campaign details and match resultsen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org

- Overview of Kenya’s opponents, upsets (Sri Lanka, Zimbabwe, Bangladesh) and New Zealand forfeitsports.ndtv.comcricket.com

- Background on Kenya’s ODI status and qualification via 1994 ICC Trophy and 1996–99 World Cupscricket.comcricket.com

- Key player profiles: Steve Tikolo (captain and top performer)skysports.com, Maurice Odumbe (all-rounder)theguardian.com, Collins Obuya (leg-spinner)icc-cricket.com, Thomas Odoyo and Kennedy Otieno contributionsen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org

- Quote and impact of coach Sandeep Patil on Kenya’s self-beliefcricket.com

- Guardian eyewitness of Kenyan victories and local reaction (Gypsies bar anecdote, public learning cricket)theguardian.comtheguardian.com

- Semi-final narrative and Indian innings detailsen.wikipedia.orgen.wikipedia.org

- Post-2003 decline: internal strikes and administration issuesskysports.comespncricinfo.com, lack of international matches (Tikolo’s complaint)espn.comespn.com, misused funds and lost opportunities (Aasif Karim interview)emergingcricket.com

- ICC and global context: only non-Test semi-finalistsen.wikipedia.org and ICC reluctance to grant Test status (caution after Bangladesh/Zimbabwe)theguardian.com

- Long-term legacy and current status as described by Kenyan cricket veteransemergingcricket.comemergingcricket.com.