Jomo Kenyatta stands as one of the most consequential figures in African political history. To many Kenyans, he remains the “Father of the Nation,” the leader who guided Kenya from colonial rule to independence in 1963. Yet, Kenyatta’s life also reflects the paradoxes of decolonization—he was both a symbol of anti-colonial resistance and an architect of centralized postcolonial authority. Between 1897 and 1978, he evolved from a mission-educated Kikuyu youth to a nationalist intellectual, a detainee of the British Empire, and finally, the president who shaped Kenya’s new political order. His writings, particularly Facing Mount Kenya (1938), reveal a deep conviction that cultural restoration was inseparable from political freedom. As Anaïs Angelo (2019) observes, Kenyatta’s presidency later embodied this philosophy, blending nationalism with paternalistic control in a project to “domesticate power” within a unified Kenyan state.

Early Life and Education (1897–1929)

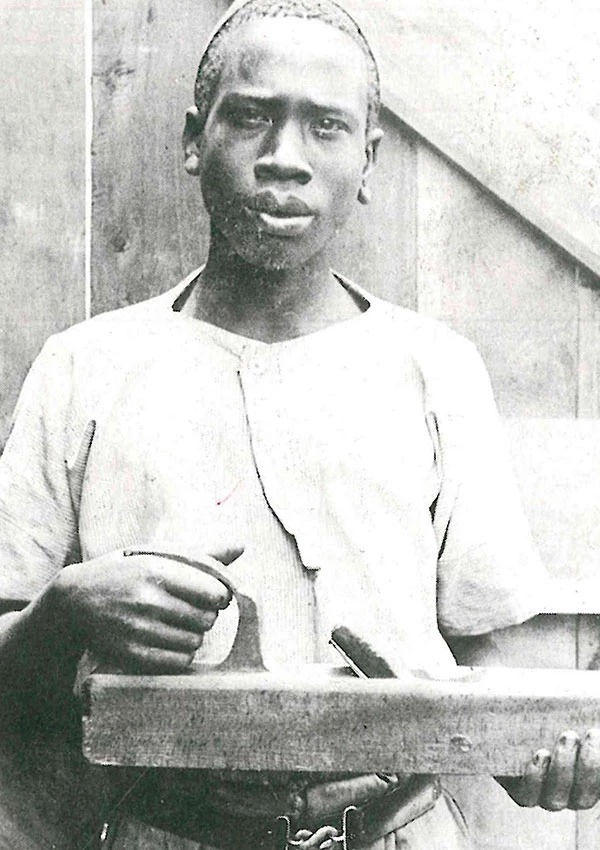

Jomo Kenyatta was born Kamau wa Ngengi around 1897 in Gatundu, in present-day Kiambu County. His early years unfolded during the rapid expansion of British colonial rule, as European settlers appropriated Kikuyu lands for the “White Highlands.” He received his first formal education at the Church of Scotland Mission School at Thogoto, where he was baptized as Johnstone Kamau. The mission experience introduced him to Western literacy and Christian values, but also exposed him to racial hierarchies that denied Africans equality (Ochieng, 1985).

In 1921, after working briefly as a store clerk and carpenter, Kenyatta became involved in the nascent Kikuyu Central Association (KCA), which sought redress for land grievances and political representation. The KCA emerged amid rising tension over land alienation and forced labor. By the late 1920s, colonial records—such as the “Kikuyu Grievances” petitions (CO 533/458/009)—show Kenyatta as one of several emissaries challenging European land monopoly, particularly in the Kiambu and Fort Hall districts. The petitions reveal a disciplined legalist tone, reflecting Kenyatta’s early belief that colonial injustices could be rectified through negotiation rather than revolt.

In 1929, KCA leaders sent Kenyatta to London as their representative. His journey marked the beginning of a political education that would expand beyond Kikuyu concerns to encompass Pan-African and anti-imperial ideologies.

Political Awakening and Pan-African Influence (1929–1946)

Kenyatta’s years in Europe transformed him intellectually and politically. In London, he enrolled at the Woodbrooke Quaker College and later at the London School of Economics, studying under anthropologist Bronislaw Malinowski. During this period, he mingled with other African and Caribbean intellectuals, including George Padmore, C.L.R. James, and W.E.B. Du Bois, who shaped his understanding of global colonialism.

In 1938, Kenyatta published Facing Mount Kenya, a study of Kikuyu life and customs. The book served both as ethnography and manifesto. He argued that British colonialism had eroded African social cohesion by dismantling indigenous systems of land ownership and initiation. “Without these rites,” he wrote, “the individual is not considered to have reached manhood, and therefore is not a full member of the tribe” (Kenyatta, 1938, p. 140). The statement was both cultural and political—an assertion that self-rule required moral and institutional independence.

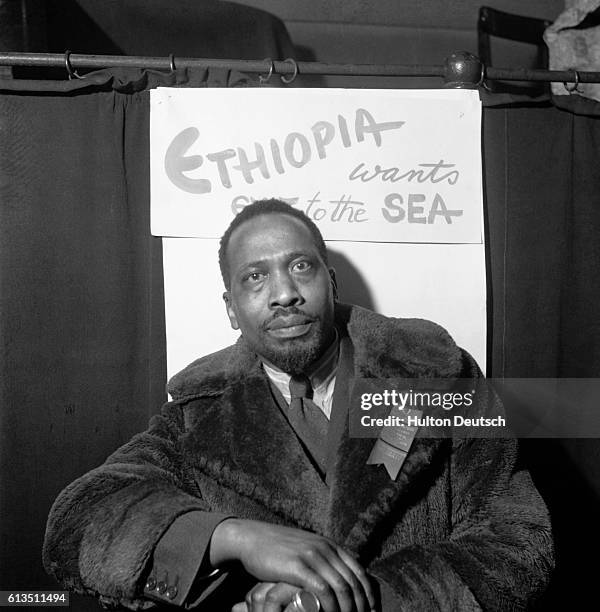

Kenyatta’s time abroad also connected him to Pan-African networks. He attended the 1945 Manchester Pan-African Congress, which linked African nationalists from across the continent. His speeches combined anthropological defense of African culture with demands for equality and self-determination. Yet, colonial officials increasingly viewed him with suspicion. Upon his return to Kenya in 1946, he was regarded as a subversive intellectual rather than a moderate reformer.

Detention and the Mau Mau Period (1952–1961)

The 1950s were the defining crisis of Kenyatta’s political career. In October 1952, following the outbreak of the Mau Mau rebellion, the British administration under Governor Evelyn Baring declared a State of Emergency and arrested Kenyatta alongside five other nationalists—Bildad Kaggia, Achieng’ Oneko, Paul Ngei, Fred Kubai, and Kung’u Karumba—collectively known as the Kapenguria Six.

The prosecution accused Kenyatta of being the “leader and inspiration” of Mau Mau, a charge he denied. The trial, held in Kapenguria, was widely criticized as political theater: evidence was circumstantial, and witnesses were coached (Elkins, 2005). Nonetheless, Kenyatta was sentenced to seven years of hard labor and indefinite restriction.

During his detention at Lokitaung and later at Lodwar, Kenyatta became a symbolic figure for the nationalist cause. His imprisonment galvanized support among diverse ethnic groups, transforming him from a regional Kikuyu leader into a national icon. Angelo (2019) notes that the colonial administration’s attempt to isolate him paradoxically magnified his authority; he became “the absent center” around whom nationalist legitimacy coalesced.

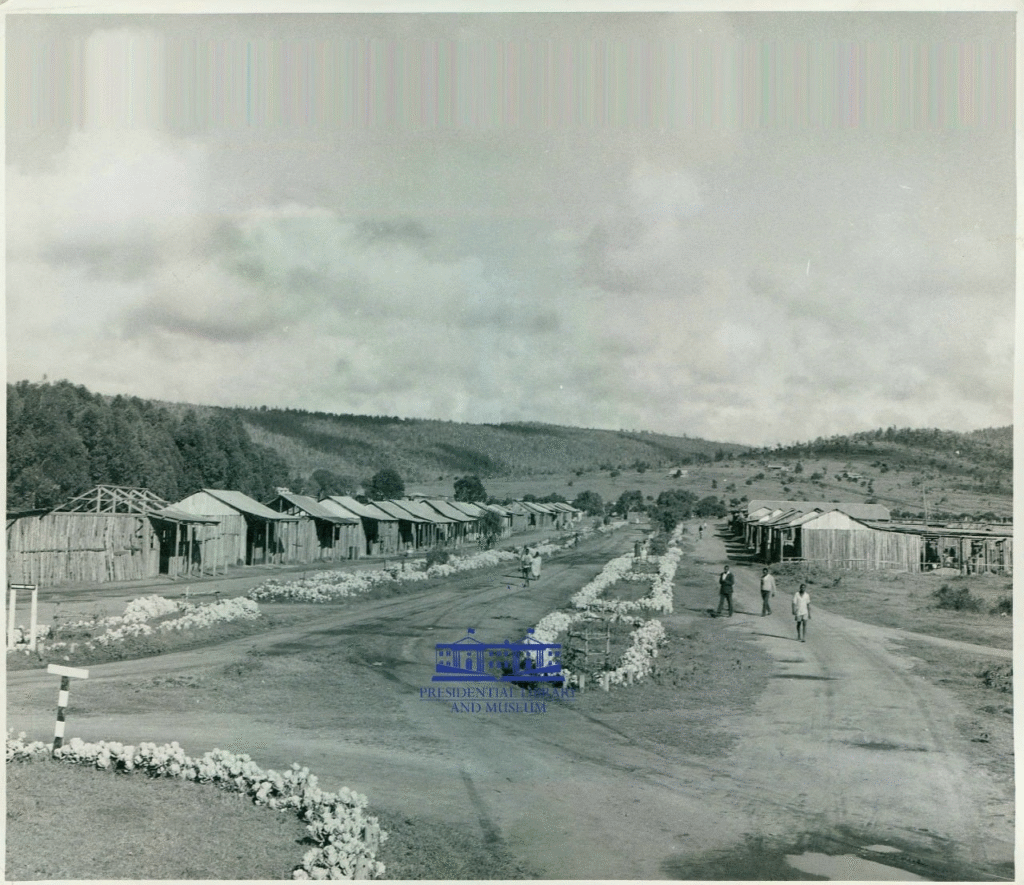

While Kenyatta was detained, the colonial government implemented brutal counterinsurgency measures—detention camps, forced villagization, and the execution of suspected insurgents. Yet, even as the Emergency revealed the coercive limits of colonial rule, it also accelerated constitutional reforms. By the time Kenyatta was released in August 1961, African representation in the Legislative Council had expanded, and the path to self-government was open.

The Road to Independence (1961–1963)

Kenyatta’s release from detention was both a political necessity and a colonial gamble. His first public words—“Harambee, let us all pull together”—signaled reconciliation rather than revenge. Britain’s strategy of gradual decolonization required a moderate African leader who could manage settler fears and nationalist impatience, and Kenyatta fit that role.

In 1961, he assumed leadership of the Kenya African National Union (KANU), which advocated for a unified, centralized state. At the Lancaster House Conferences (1960–1963), Kenyatta’s delegation negotiated Kenya’s independence constitution, securing majority rule while accommodating limited regional autonomy. These talks also addressed the sensitive land question, proposing settlement schemes to buy out European farmers through British aid.

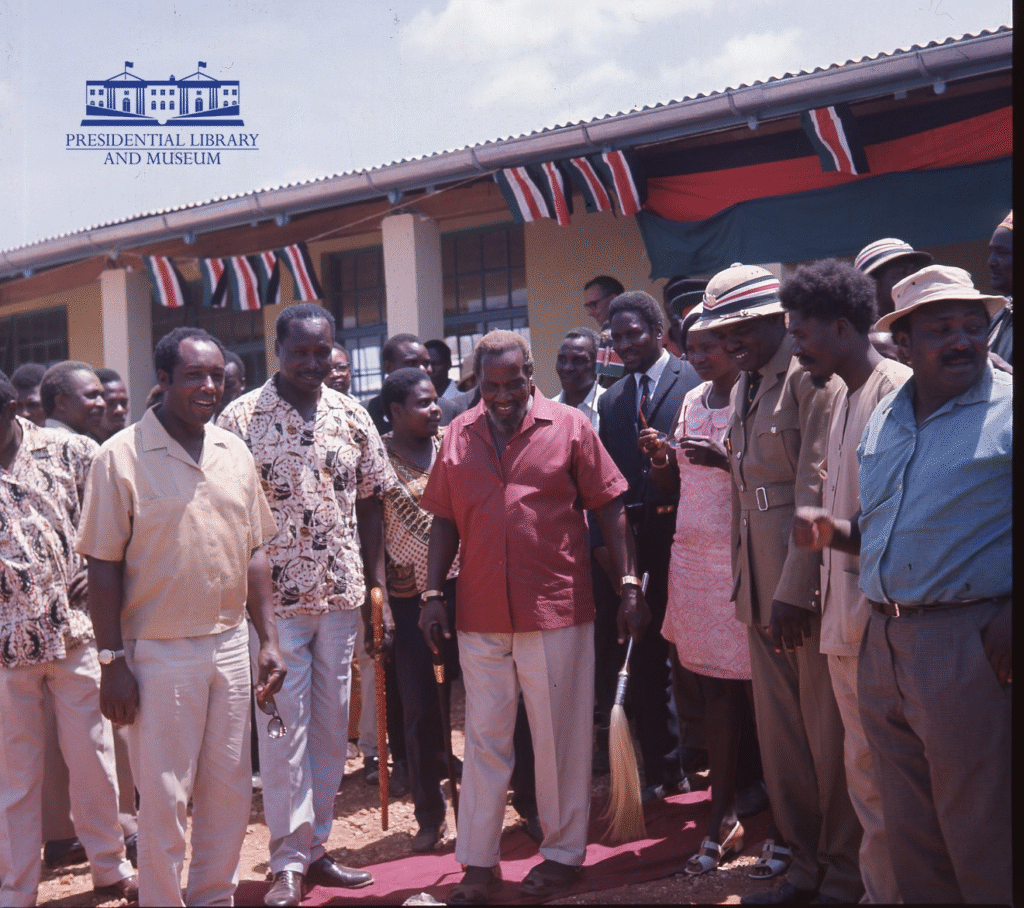

Kenyatta’s charisma and political pragmatism reassured both African and European constituencies. His message—“Forgive but not forget”—positioned him as a statesman of reconciliation. When Kenya attained internal self-government in June 1963, Kenyatta became prime minister, and on December 12, 1963, he presided over independence as the country’s first head of government. The following year, with the republic declared, he became Kenya’s first president.

The Presidency (1963–1978)

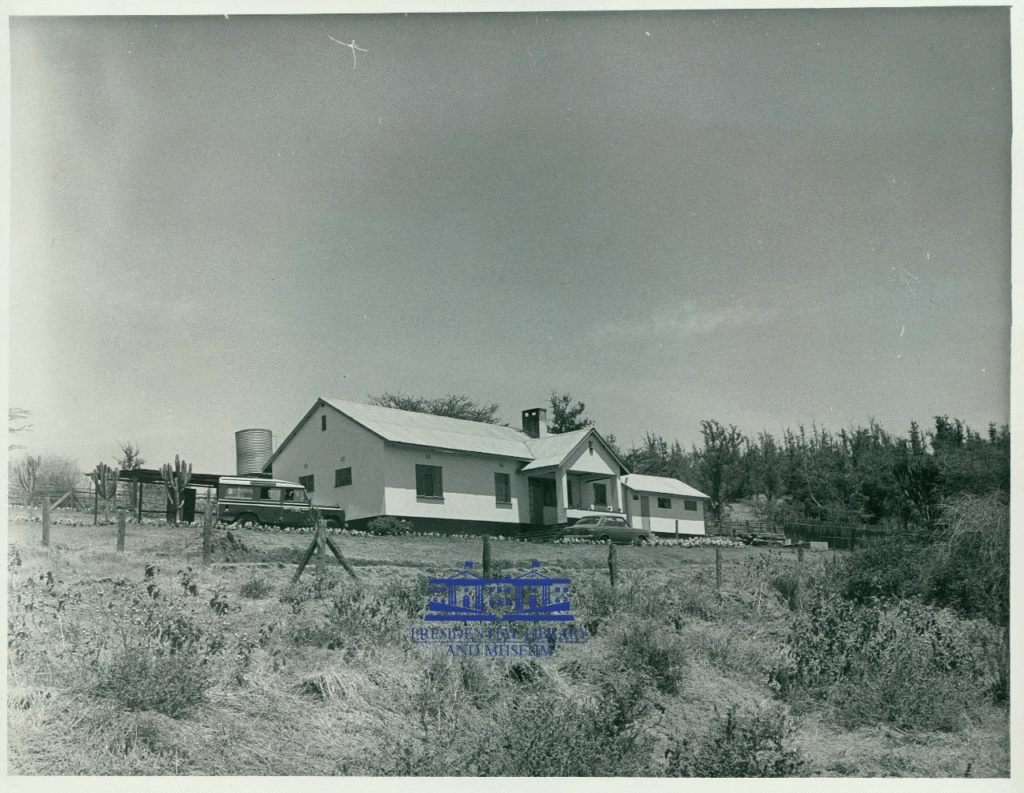

Kenyatta’s presidency combined economic modernization with authoritarian centralization. His early government prioritized stability, land redistribution, and economic growth under a capitalist framework. The Million Acre Settlement Scheme, financed by British aid, resettled thousands of landless Africans, though most beneficiaries were politically connected elites rather than the poorest peasants (Angelo, 2019).

Kenyatta quickly consolidated power around himself and a close circle of loyalists, many from his Kikuyu community. By 1964, the opposition Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU) had dissolved, ushering in de facto one-party rule. In 1969, the banning of the Kenya People’s Union (KPU) after the Kisumu Massacre formalized Kenya as a one-party state under KANU.

As president, Kenyatta projected an image of patriarchal authority—Baba wa Taifa, the father of the nation. Angelo (2019) characterizes his style as “the personalization of power,” where governance revolved around patronage and symbolic legitimacy rather than institutional checks. The provincial administration became an extension of presidential will, with provincial commissioners and chiefs answerable directly to State House.

Economically, Kenya experienced relative stability and growth during his tenure, aided by foreign investment and a cautious pro-Western stance. Nairobi emerged as a regional financial hub, and Kenyatta promoted Africanization of the civil service. Yet, the benefits of growth were unevenly distributed. Scholars such as Berman (1990) and Ochieng (1985) note that the new African elite reproduced colonial inequalities: land concentration, ethnic patronage, and rural marginalization persisted under African rule.

Kenyatta’s foreign policy was pragmatic. He maintained cordial relations with Britain, avoided Cold War entanglements, and championed regional cooperation through the East African Community. His government, however, suppressed internal dissent. The assassinations of Pio Gama Pinto (1965) and Tom Mboya (1969) signaled a closing of democratic space. By the mid-1970s, Kenyatta’s health was declining, and governance increasingly depended on his inner circle—known as the “Kiambu Mafia”—which jockeyed for succession.

Legacy (1897–1978)

When Jomo Kenyatta died on August 22, 1978, he left behind a nation that had avoided the chaos of many postcolonial states but remained deeply unequal. His leadership had steered Kenya through a stable first decade, yet it entrenched patterns of centralized authority that would define its politics for decades.

Kenyatta’s intellectual and political legacy lies in the fusion of cultural nationalism and statecraft. In Facing Mount Kenya, he had written that “a people without a past is a people without dignity.” His presidency sought to reclaim that dignity through African-led governance, but it also silenced dissent in the name of unity. As Angelo (2019) observes, Kenyatta transformed the presidency into a sacred office—a symbol of national fatherhood that blurred the line between state and person.

To many Kenyans, Kenyatta remains both liberator and patriarch. His face adorns currency, his mausoleum stands at the center of Nairobi, and his name continues to define political dynasties. Yet, the contradictions of his rule—the co-existence of freedom and fear, nationhood and nepotism—still echo in Kenya’s contemporary politics. His life, spanning colonial subjugation to sovereign leadership, mirrors Kenya’s own journey: from the struggle for dignity to the challenge of governing it.

References

Angelo, A. (2019). Power and the Presidency in Kenya: The Jomo Kenyatta Years. Cambridge University Press.

Berman, B. (1990). Control and Crisis in Colonial Kenya: The Dialectic of Domination. James Currey.

Elkins, C. (2005). Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya. Henry Holt.

Kenyatta, J. (1938). Facing Mount Kenya: The Tribal Life of the Gikuyu. Secker and Warburg.

Ochieng, W. R. (1985). Autobiography in Kenyan history. Ufahamu: A Journal of African Studies, 13(3), 7–17.

United Kingdom Colonial Office. (1930s). CO 533/458/009: Kikuyu Grievances and the Central Association Petitions. National Archives, London.