Jaramogi Ajuma Oginga Odinga (1911–1994) was Kenya’s first Vice President and its most enduring symbol of opposition politics. His life mirrors the birth of the Kenyan nation itself—an arc that stretched from colonial subjugation to independence, from national unity to the bitter politics of betrayal. To his admirers, Oginga was a man ahead of his time, a believer in African socialism and people-centered governance. To his critics, he was obstinate, radical, and unable to compromise. Yet his story cannot be told apart from that of Kenya’s postcolonial identity and its uneasy balance between freedom and control, ideals and power.

Early Life and Education (1911–1946)

Born in Sakwa, Bondo District, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga grew up in a Luo community that prized education as a route to liberation. He studied at Maseno and later Makerere College, among the few Africans of his generation to achieve higher education. His early years as a teacher exposed him to the contradictions of colonial life — African intellectuals educated enough to serve but never to rule.

It was here that Odinga began forming his worldview: independence was not only political but also economic. As he later wrote in Not Yet Uhuru (1967), “Freedom that cannot feed the people is a shadow.” His early belief in self-reliance would guide much of his later activism, especially his advocacy for African cooperatives and local enterprise.

Building Economic Nationalism

In the late 1940s, Odinga left teaching and founded the Luo Thrift and Trading Corporation (LUTATCO). It was an experiment in African capitalism — an effort to reclaim space from settler-controlled trade networks. Through the Luo Union, he helped unite diaspora communities in urban centers like Nairobi and Kisumu, demonstrating how ethnic identity could serve both solidarity and economic organization.

Odinga’s grassroots mobilization coincided with rising unrest in the highlands, where African grievances over land and inequality were fueling resistance movements. Though Odinga did not take part in the armed struggle, he sympathized with its cause. His political speeches during the 1950s echoed the frustrations that would soon explode into the Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya (1952–1960), calling for Kenyans to reclaim both their dignity and their soil.

In 1957, he penned a letter to the U.S. Armed Services Committee, arguing that Britain’s repression of African self-rule contradicted the democratic ideals it claimed to defend. This international approach to Kenya’s struggle foreshadowed the diplomatic strategy that later defined his politics — seeking freedom through both local mobilization and global solidarity.

Rise in National Politics (1957–1963)

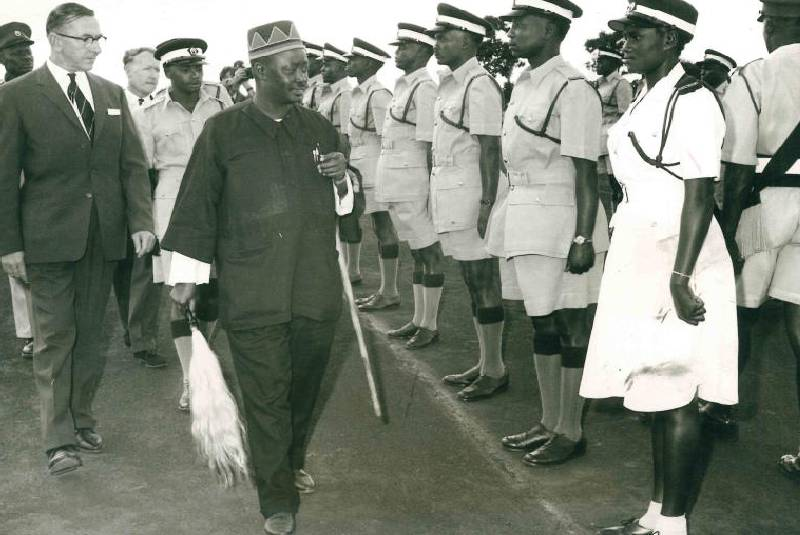

Oginga Odinga’s formal political journey began when he was elected to the Legislative Council (LEGCO) in 1957, representing Central Nyanza. He quickly rose as a voice for detained nationalists, demanding the release of Jomo Kenyatta and other leaders. When Kenyatta was freed in 1961, Odinga deferred to him, declaring, “Kenyatta is our chosen leader.”

This alliance reflected Odinga’s deep belief in unity as the cornerstone of independence. Together with Tom Mboya, James Gichuru, and others, he helped form KANU in 1960, an organization that replaced fragmented ethnic groups with a united African front. Kenya’s independence in December 1963 elevated Kenyatta to Prime Minister and Odinga to Minister for Home Affairs. When the country became a republic in 1964, he rose to the post of Vice President — the second most powerful man in the new state.

For more on how the British left behind a centralized political machine that shaped this government, see Kenya’s Colonial Administration (1920–1963).

Ideological Rift with Kenyatta (1964–1966)

Oginga Odinga’s vision of independence differed sharply from Kenyatta’s. The president and his circle favored a capitalist path, encouraging foreign investment and European partnerships. Odinga believed Kenya needed socialist policies to correct colonial imbalances. His argument was simple: political freedom meant little without economic redistribution.

By 1965, their alliance had collapsed. Odinga was sidelined within the cabinet, his supporters transferred or dismissed. In 1966, he resigned as Vice President and founded the Kenya People’s Union (KPU) — the country’s first formal opposition party. The move was unprecedented; Kenya’s politics had revolved around unity, not dissent.

KPU’s ideology drew heavily from Odinga’s 1967 book Not Yet Uhuru, a political manifesto that warned of “a new colonialism by our own people.” The party attracted left-leaning intellectuals, trade unionists, and communities that felt excluded from the Kenyatta state. Its formation mirrored early calls for regional autonomy, echoing themes later explored in Majimbo Dreams: Kenya’s Lost Federalism.

The Kisumu Massacre and Detention (1969–1980)

The rivalry between Kenyatta and Odinga came to a tragic head on October 25, 1969, when the president visited Kisumu to open the Russian-built New Nyanza Hospital. What began as a public event quickly turned into confrontation — angry crowds jeered Kenyatta, and security forces opened fire. The incident left dozens dead and marked one of the darkest moments in Kenya’s early independence years.

KPU was banned immediately after, and Odinga was placed under house arrest. The episode underscored the fragility of Kenya’s new nationhood: unity built on fear, not consensus. The details of that event are captured in The Kisumu Massacre of 1969: Independence Betrayed.

For the next decade, Odinga lived under surveillance. He was released after Kenyatta’s death in 1978, but his political rights were restricted. Under Daniel arap Moi, he was allowed to travel and speak cautiously — yet his ideas of equality, justice, and multiparty governance never faded.

Return and the Second Liberation (1980–1992)

In the 1980s, as Kenya slid toward authoritarian rule, Odinga once again became a rallying figure for reformists. He denounced Moi’s 1982 amendment making Kenya a one-party state, declaring it “a betrayal of the blood shed for freedom.” His home in Kisumu became a meeting place for activists, clergy, and students who would later lead the struggle for democracy.

By 1991, international pressure and internal protests forced Moi to repeal Section 2A of the constitution. Odinga, now in his eighties, helped form the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy (FORD), a broad coalition that reignited the spirit of resistance. When FORD later split, he led FORD–Kenya into the 1992 general elections. Though he did not win, his participation legitimized Kenya’s re-entry into multiparty democracy.

The broader historical context of this movement is discussed in The Birth and Evolution of Kenya’s Multiparty Democracy— a story that begins where Odinga’s ended.

Legacy and Death (1994)

Oginga Odinga died on January 20, 1994, at his Kisumu home. His funeral drew crowds from across the country — peasants, intellectuals, former detainees, and even political rivals. He left behind a complex legacy: a man whose courage inspired generations, yet whose radicalism made him a perpetual outsider.

Through his son Raila Odinga: Political Life and Legacy in Kenya, his ideas of social justice and constitutional reform continued to influence Kenya’s political imagination. The father had fought for freedom from colonial rule; the son would battle for freedom from one-party rule.

Oginga’s ideological duel with Jomo Kenyatta: Power, Nationhood, and the Making of Postcolonial Kenya (1897–1978) framed the nation’s early divisions — between state and opposition, wealth and equality, conformity and conscience.

He remains the embodiment of Kenya’s unfinished struggle: the quest for a just society where, in his own words, “Uhuru means bread, peace, and dignity for all.”

Read Next on KenyanHistory.com

- Raila Odinga: Political Life and Legacy in Kenya

- The Kisumu Massacre of 1969: Independence Betrayed

- The Birth and Evolution of Kenya’s Multiparty Democracy

References (APA)

Odinga, O. (1957). Letter to the Delegation Head, U.S. Armed Services Committee. Washington, D.C.

Odinga, O. (1967). Not Yet Uhuru: The Autobiography of Oginga Odinga. Nairobi: East African Publishing House.

Opondo, P. A. (2014). Kenyatta and Odinga: The harbingers of ethnic nationalism in Kenya. Global Journal of Human-Social Science: History, Archaeology & Anthropology, 14(3), 15–25.

Subalternity and Resistance in Kenya. (1997). Journal of Eastern African Studies, 3(2), 115–134.

HISTORY CHAPTER 7. (2019). Kenyan Nationalists and the Road to Independence. Nairobi: Ministry of Education Archive Series.

This is very intriguing, educative and informative history of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga and our nation. Its indeed “Not yet Uhuru” the struggle continues