History remembers loudly. It sings the names of martyrs on the mountains — Kimathi, Muthoni, Kĩmathi, Mbiyũ — and carves their legacies into the misted ridges of the Aberdares. But in the thunder of rebellion and the canon of national memory, some stories fell silent. Between the forest and the train tracks, the Kamba took oaths. Then, history forgot to look back.

This is their story.

The Railway Was Their Battlefield

By the early 1950s, the Kenya–Uganda Railway had become a living artery of rebellion. Beneath its steel pulse ran whispers, parcels, and coded nods. For Kamba men in Nairobi, many of whom worked the railway yards, Mau Mau found an unlikely highway.

British intelligence, by 1954, privately conceded what it had long denied — that most Kamba railwaymen in the capital had already taken the Mau Mau oath (Osborne, 2010). The empire’s own workforce had turned the railway into a covert courier system. Fighters, food, and messages moved quietly between stations, wrapped in linen sacks or concealed in coal wagons.

One stop became legendary: Emali. To most passengers, it was a sleepy midpoint between Makueni and Machakos. To the resistance, it was a bridge between worlds — a meeting ground where Kikuyu oath administrators met their Kamba counterparts. Under kerosene light and ancestral silence, oaths were renewed and routes planned.

(For context on how the railway built both a colony and a rebellion, see the story of the tracks that tied Kenya to empire).

Oaths, Ash, and Arusha

The Kamba did not stumble into rebellion; they were drawn into it.

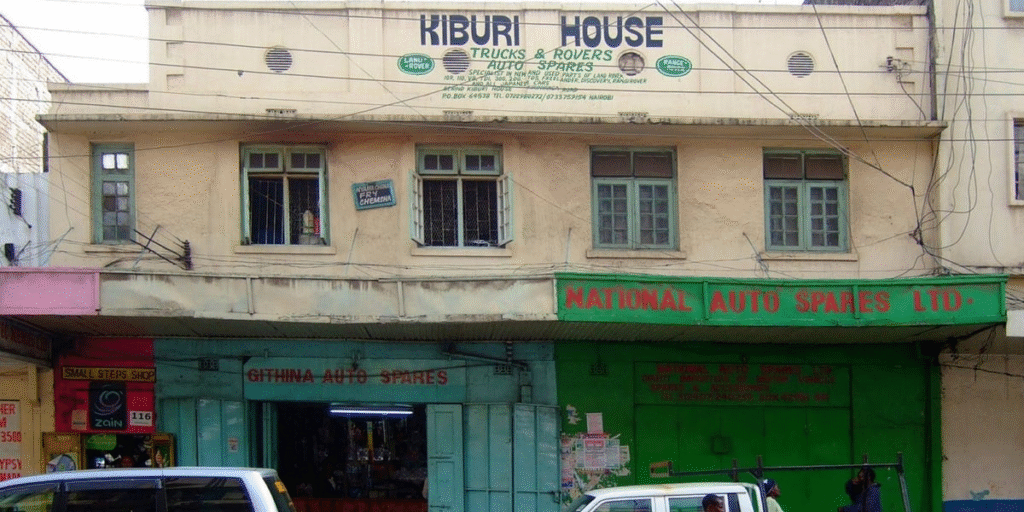

Paul Ngei, a fiery nationalist and future cabinet minister, served as assistant secretary of the Kenya African Union’s Nairobi branch. It was Ngei who escorted young Kamba men to Kiburi House, the underground heart of Mau Mau operations in the city. There, before senior oath administrators, they pledged secrecy and allegiance — blood for blood, land for freedom.

Some recruits wept; others left wordless, already mapping the distance between Nairobi’s Eastleigh backstreets and the Aberdares. The movement spread outward: Kaloleni, Machakos, Kitui. Some carried the oath as far as Arusha, stitching an invisible thread of defiance across borders.

Among them were men the British later labelled the “Passive Wing” — civilians who fought without rifles, using the infrastructure of empire itself. Railway drivers ferried coded letters. BAT employees smuggled food to forest fighters. In the machinery of colonial order, Mau Mau built its own underground rail.

(A similar quiet fire once burned in the coastlands under Mekatilili wa Menza’s defiance, where rebellion moved through ritual rather than open battle.)

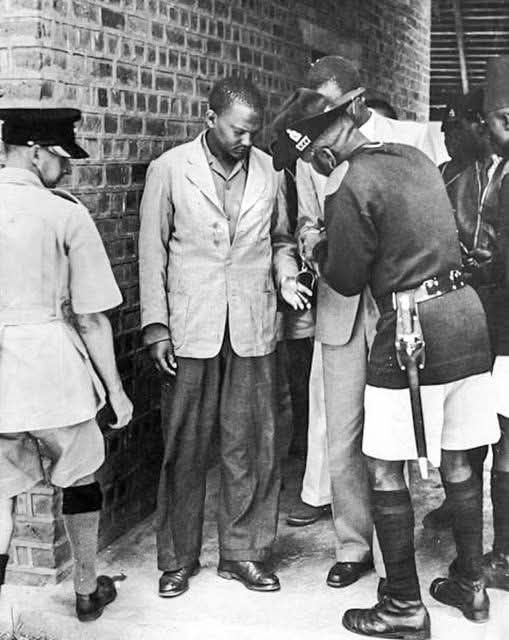

Betrayed by Chiefs, Watched by the State

The British response was not a single blow, but a quiet dissection. Officials redrew borders and manipulated loyalty as policy. In 1953, the colonial government carved out a new administrative zone — the Southern Province — effectively isolating Machakos and Kitui from the rebellion’s Central heartlands. The aim was simple: to prevent what one District Commissioner called “Mau Mau contamination” from spreading south (Osborne, 2010).

Development became a weapon. Roads, schools, and cash-crop projects were poured into loyalist zones, creating the illusion of progress while muting dissent. Chiefs like Kasina wa Ndoo, celebrated at flag-raising ceremonies and gifted medals, embodied what the British called the “loyal martial race.” The policy worked — at least on paper.

But beneath the surface, resistance smouldered.

Detention camps sprang up in Machakos, small but brutal. Kathonzweni, Thwake, and Kaasya became part of what colonial officers called the Kamba Pipeline — a system that filtered suspected oath-takers away from Kikuyu detainees. Some were screened at Embakasi, others tortured and “rehabilitated” in isolation. They left no graves, only silence.

(The machinery of control mirrored other colonial atrocities, including the events later exposed in the Hola massacre).

General Kavyu and the Forest That Whispers

Not everyone stayed behind.

In the Aberdares, Mau Mau archives name a Kamba commander known as General Kavyu — the Knife. He led more than a thousand fighters, earning his title from his weapon of choice and his unflinching discipline. A Meru veteran later recalled that “in every group of thirty fighters, there were five or six Kamba.”

That math rewrites the myth. Mau Mau was never tribal. It was multilingual, multi-ethnic, bound by hunger and oath rather than language or lineage.

Kavyu’s units were fast and fierce — lightly armed, impossibly loyal. They vanished as suddenly as they struck, leaving behind a trail of coded songs and quiet graves.

The Aftermath: The Fire Went Home

When the war ended, the Kamba went home. Not to parades or pensions — just to debt, land disputes, and silence. Paul Ngei entered politics, his Mau Mau past polished into a footnote. The rest returned to anonymity, their contributions erased by official narratives that celebrated loyalism and ignored dissent.

Yet memory persisted. At Emali Station, some families still whisper the names of the disappeared. Others keep medals their fathers never received — hand-forged, not awarded. Their stories linger like smoke: visible only when the light catches at the right angle.

(The long silence that followed recalls the muted aftermath explored in Kenya’s colonial detention system and its legacies).

Not Just the Forest: The Tracks Bled Too

Kenya’s independence was not won solely in the forests of Central Kenya. It was also smuggled through train carriages, hidden beneath sacks of maize, and carried in the calloused hands of Kamba railwaymen who chose oath over obedience.

Their rebellion was quieter, but no less fierce.

Their silence was strength.

And in their forgetting, we are reminded