George Musengi Saitoti remains one of the most consequential figures in Kenya’s post-independence political history, yet also one of its most elusive. For more than thirty years, he moved quietly within circles where men rarely survived long. He managed to navigate a political landscape designed to crush dissent, bury rivals, and reward blind loyalty. And yet, he outlasted many of the loudest and most charismatic players of his era.

Saitoti was not a conventional politician. He was not a master orator. He did not rely on ethnic mobilisation. He did not cultivate a personality cult. His strength came from something Kenya rarely values in its politicians: intellect, discipline, and patience. He was a mathematician who wandered into the furnace of Kenyan politics and spent the rest of his life walking its tightrope with a calm that unsettled both allies and enemies.

His life raises questions that continue to puzzle Kenyans:

Who exactly was George Saitoti?

What made him survive where others fell?

Why did he never fully belong to any political faction?

And what, ultimately, did Kenya lose when he died?

To understand Saitoti is to understand the structure of Kenyan power between the 1970s and early 2010s — a structure built on identity, loyalty, fear, and the careful balancing of ambition. Saitoti understood those ingredients better than anyone else.

1. Early Life: A Childhood Built on Ambiguity and Opportunity

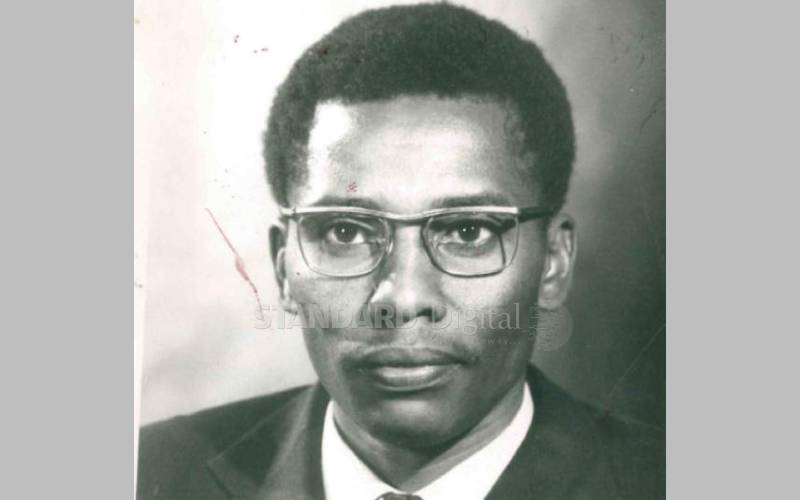

George Musengi Saitoti was born in 1945 in Kajiado. The official record places him squarely within the Maasai community, and publicly he embraced that identity throughout his career. But within Kenya’s political class, it was widely acknowledged that his lineage was more complicated. Saitoti had both Maasai and Kikuyu roots — a fact he rarely discussed, and one Kenya never fully resolved.

This ambiguity shaped his future. Kenya is a country where identity is never just cultural; it is political currency. Being part-Maasai and part-Kikuyu placed him in a unique category. He belonged to two of the most influential communities in the country without being fully claimed by either. This made him politically mobile. It also meant he never truly had a tribal home that could rally around him in moments of crisis.

But in a political system obsessed with loyalty blocs and ethnic patronage, his hybrid identity gave him an unusual advantage. He could move across networks, negotiate conflicts with ease, and position himself as a neutral actor. Presidents found him useful because he did not carry a large ethnic base that could threaten their power. Yet he carried enough cultural legitimacy to be accepted nationally.

In many ways, Saitoti’s earliest strength was that he did not fit into Kenya’s predictable categories.

2. The Mind That Outpaced His Time

Before he became a politician, Saitoti was a scholar — and a brilliant one. His academic journey began at Mang’u High School, which has produced some of Kenya’s most influential minds. From there, he studied mathematics at the University of Nairobi, then pursued postgraduate degrees in Europe and the United States.

He specialised in algebraic topology, one of the most abstract and challenging branches of mathematics. This was not a field for ordinary minds. It requires patience, precision, and an ability to see patterns where others see chaos. These traits would later shape his political style.

By his early thirties, he was a full professor — one of the youngest on the continent — and head of the mathematics department at the University of Nairobi. He earned international respect as a researcher and educator. In a different world, Saitoti might have remained an academic and contributed to global mathematics. But Kenya was entering a political phase where the state demanded educated African technocrats, and the quiet professor soon caught the attention of the man who would redefine his life.

3. From Lecture Hall to Cabinet: Moi’s Ideal Technocrat

When Daniel arap Moi assumed the presidency in 1978, he was surrounded by networks built during the Kenyatta era. Many of these individuals did not trust him. Moi needed new allies — people who were competent, loyal, unaligned with the old Kiambu establishment, and too independent to be manipulated by political factions.

Saitoti was the perfect fit.

He was:

- intellectually formidable,

- professionally disciplined,

- ethnically ambiguous,

- politically neutral,

- and personally discreet.

Moi appointed him to Parliament through a nomination slot, then brought him into cabinet. Within a short time, Saitoti was placed at the heart of economic management as Minister of Finance.

This was not a ceremonial appointment. In the early 1980s, Kenya was struggling with rising debt, inflation, donor pressure, and political insecurity. The Ministry of Finance required someone who could reassure investors, understand international economics, and maintain stability while Moi consolidated power.

Saitoti became indispensable.

4. The 1982 Coup Attempt: A Stress Test for the Treasury

The August 1, 1982 coup attempt remains a turning point in Kenya’s political history. It was a moment of national trauma that reshaped governance, military structures, and political expression for decades.

For Saitoti, it was also a test of survival.

In the aftermath, the country experienced:

- capital flight,

- currency instability,

- severe donor scrutiny,

- public fear,

- and a near paralysis of the civil service.

Moi spent months purging perceived enemies from the military and universities. While security organs went into overdrive, it was Saitoti’s job to keep the economic system functioning. He restored confidence, steadied public finances, and reassured international partners that Kenya would not collapse.

This period deepened Moi’s trust in him. Saitoti had proven that he would not only obey orders but also deliver results under pressure.

He was now part of the hard centre of state power.

5. The Vice Presidency: Ten Years Under a Watchful President

In 1989, Moi appointed Saitoti as Kenya’s Vice President — a position he held for nearly a decade. It was one of the longest and most stable vice-presidential tenures in Kenya’s second republic.

The VP seat was traditionally a revolving door. Moi often used it to discipline, reward, or neutralise ambitious politicians. Yet Saitoti lasted longer than nearly all his predecessors because he understood the logic of survival under Moi.

He remained:

- loyal but not sycophantic,

- powerful but not threatening,

- intelligent but not flamboyant,

- visible but not dominant.

He mastered a delicate balancing act. He did not challenge Moi’s authority. He did not build an ethnic militia. He did not attack rival political figures directly. His survival depended on being useful but not indispensable, loyal but not suspicious, competent but not too popular.

But even from the centre of power, Saitoti never fully became a national darling. He commanded respect but not affection, influence but not devotion.

6. Goldenberg: The Scandal That Shadowed a Career

Goldenberg became one of the most notorious economic scandals in Kenya’s history. As Minister of Finance during the period when the export compensation scheme was introduced, Saitoti’s name became entangled in the controversy.

However, a closer examination reveals a more nuanced story:

- He did not design the fraudulent scheme.

- Many illegal transactions occurred outside his office.

- Senior government officials and businessmen manipulated loopholes after the fact.

- A judicial review later cleared him of personal wrongdoing.

The Court of Appeal exonerated him, noting that he was not responsible for the fraudulent aspects of the scheme. But for many Kenyans, the association was enough to taint his reputation.

It was a burden he carried for the rest of his life.

7. Reinvention in the Narc Era: A Second Life in Politics

When KANU fell in 2002, Saitoti reinvented himself yet again. He joined Narc and campaigned for Mwai Kibaki. For many KANU-era politicians, this transition was humiliating. For Saitoti, it was strategic.

Kibaki appointed him Minister for Education, one of the most impactful portfolios in the new government. Here, Saitoti oversaw the rollout of Free Primary Education — a flagship policy that transformed the lives of millions of Kenyan children.

His performance in the ministry earned him public admiration and proved he could function outside the authoritarian structures of the Moi era. He was no longer just a technocrat. He was a reformer.

Even the Anglo-Leasing purge, which briefly removed him from cabinet, resulted in a legal victory that strengthened his position.

He came back cleaner, stronger, and more determined.

8. Internal Security: The Most Powerful Portfolio

Between 2008 and 2012, Saitoti served as Minister of Internal Security, placing him at the centre of Kenya’s security and intelligence apparatus. This was during a volatile period marked by:

- post-election tensions,

- rising terrorism threats,

- police reform debates,

- militia violence,

- and cross-border insecurity.

His leadership was characterised by a strict, sometimes heavy-handed approach. He presided over crackdowns on organised crime gangs, managed early responses to Al-Shabaab infiltration, and oversaw major reforms in the police force.

It was during this period that he delivered one of his most quoted lines:

“There comes a time when the nation is more important than an individual.”

It was not rhetoric. It was a statement of political philosophy — the thinking of a man who believed in the primacy of the state.

9. The 2012 Break: A Presidential Bid Interrupted

By 2012, Saitoti was preparing for a presidential run. He had the credentials, the networks, and the experience. But he lacked a single, solid ethnic base — something Kenyan succession politics rarely forgives.

Still, he was positioned as a serious contender.

Then came June 10, 2012.

The police helicopter carrying Saitoti and Assistant Minister Orwa Ojode crashed in Ngong Forest. The official report cited mechanical failure. But the public viewed the timing with suspicion. Kenya was entering an intense succession period, and Saitoti’s death became one of the most debated political tragedies of the decade.

Whether accident or otherwise, his death altered the trajectory of Kenya’s political future.

10. Legacy: Kenya’s Quiet Architect

George Saitoti’s legacy is complicated but undeniable. He was:

- one of Kenya’s most educated leaders,

- a long-serving vice president,

- a national stabiliser during crisis,

- an architect of major economic policies,

- an education reformer,

- a security sector leader,

- and a presidential contender whose life ended before the race began.

He operated in the shadows, not the spotlight. He forged alliances quietly, not theatrically. He combined academic discipline with political caution. He endured storms that destroyed louder politicians.

Saitoti represents a rare breed in Kenyan politics:

a man who understood power, navigated it with precision, and left behind a legacy defined not by bluster, but by competence.

His story is a reminder that Kenya’s political history has its loud figures — and then it has its architects.

George Musengi Saitoti was one of the architects.