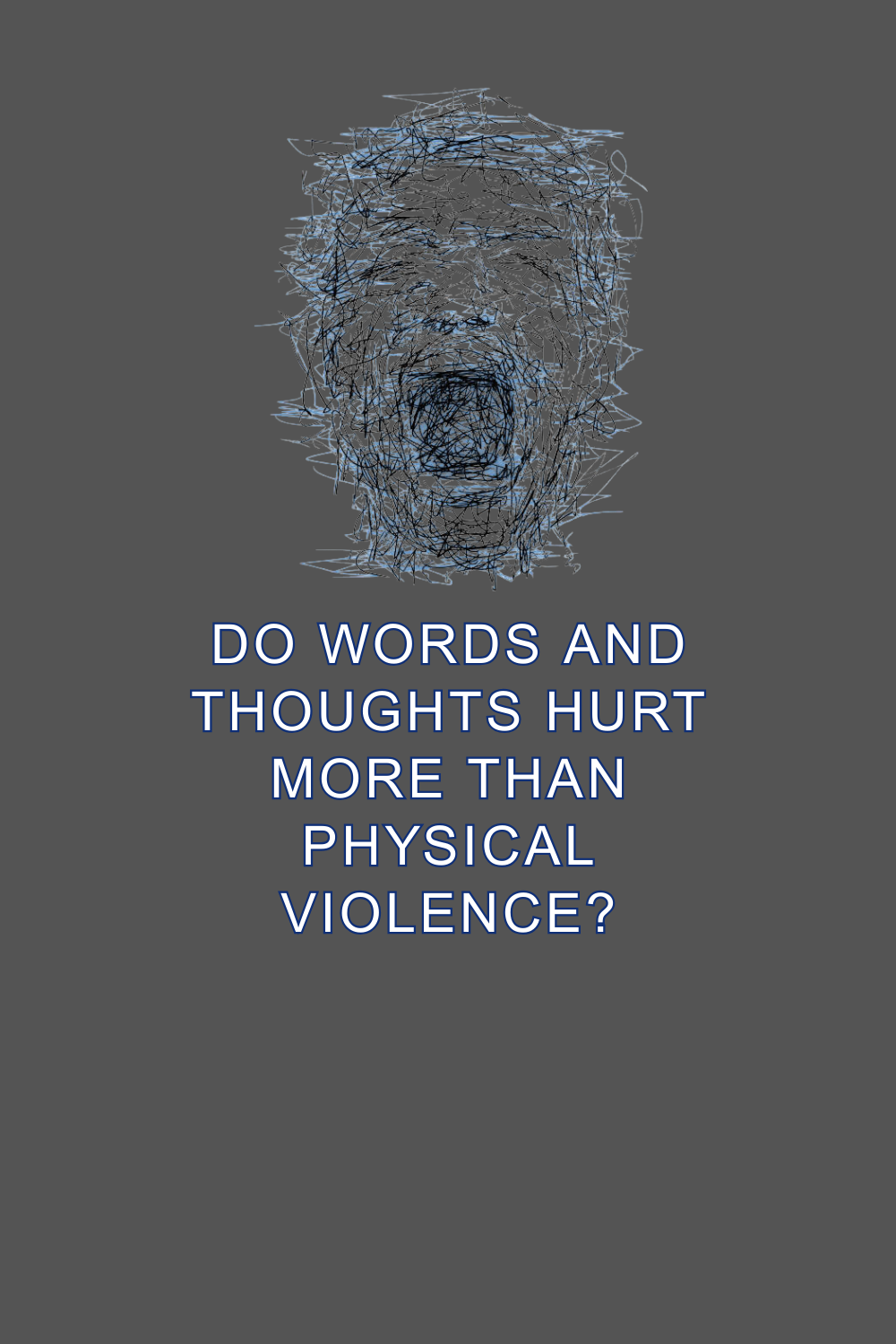

Kenya’s current political environment presents a chilling question: Are words and symbols potent enough to rival physical violence in their capacity to harm? The disappearance of critics like Kibet Bull, alongside the vanishing of several others amid allegations of a “psychological warfare” aimed at the presidency, brings this question to the forefront. The ongoing struggle highlights the intense interplay between freedom of expression, political accountability, and state response in Kenya.

A Brief History of Violence in Human Society

Violence has been a constant in human history, shaping civilizations, power dynamics, and the very structure of society. From primitive tribal conflicts to modern state wars, its evolution mirrors humanity’s struggle to reconcile primal instincts with the demands of organized living. Sigmund Freud, in his discourse with Albert Einstein, traced the roots of violence to humanity’s earliest days, where brute force was the primary means of resolving conflicts. The transition from raw power to the establishment of laws marked a significant step in taming violence, channeling it into a structured framework governed by collective will.

Male Alliances

The Evolution of Societal Patriarchy.

In many primate species, alpha males dominate access to mates and resources through aggression. This model of “alpha tyranny” ensures their reproductive success but fosters resentment among subordinate males. However, human evolution introduced a radical shift. Around 300,000 years ago, advancements in language allowed beta males to form coalitions, enabling them to plan and execute the elimination of domineering alphas. This pivotal change democratized male dominance, replacing the brute hierarchy of one with the collective power of many.

These alliances didn’t merely end alpha tyranny—they laid the groundwork for societal norms and law. The beta coalitions leveraged their collective strength to establish rules that benefited their group, simultaneously suppressing rivals and controlling women. This foundation evolved into societal patriarchy, where male alliances institutionalized power structures that prioritized their interests over others, including women and non-conforming males.

Importantly, Wrangham’s research emphasizes that these alliances were not purely self-serving; they facilitated cooperation and group stability. However, this cooperation often came at the expense of inclusivity and equity, embedding systemic biases that persist in modern institutions like law and governance.

Anthropologists and historians have documented how early societies relied on violence not only for survival but also for asserting dominance. The development of tools and weapons amplified the scale of violence, turning small skirmishes into organized warfare. Over time, the consolidation of communities into states introduced the concept of a monopoly on violence, as articulated by sociologist Max Weber. States assumed the role of regulating violence, claiming exclusive authority to use force in maintaining order and safeguarding citizens.

Despite this progress, violence remained embedded in political and social systems. Colonial conquests, for example, often employed violence as a tool of control, leaving legacies of trauma in societies like Kenya. The Mau Mau Uprising (1952–1960), a pivotal moment in Kenya’s history, exemplified resistance against colonial oppression and the centrality of violence in liberation struggles.

In modern contexts, violence has taken new forms, including psychological and symbolic dimensions. Political satire, dissent, and criticism challenge power structures without physical confrontation, yet their repercussions often evoke physical responses. This shift reflects an ongoing tension: as societies strive to minimize violence, they must navigate the boundaries between freedom of expression and the perceived need for control. Understanding this history underscores the complexity of addressing violence in any form.

A New Age of Political Weaponry

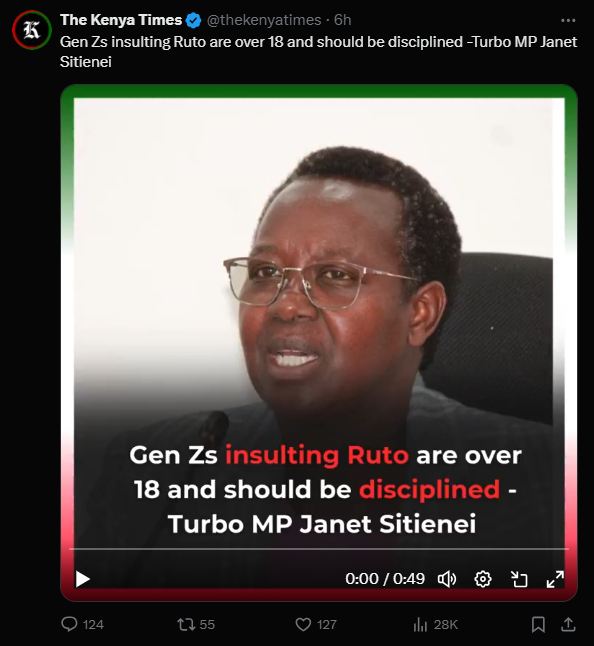

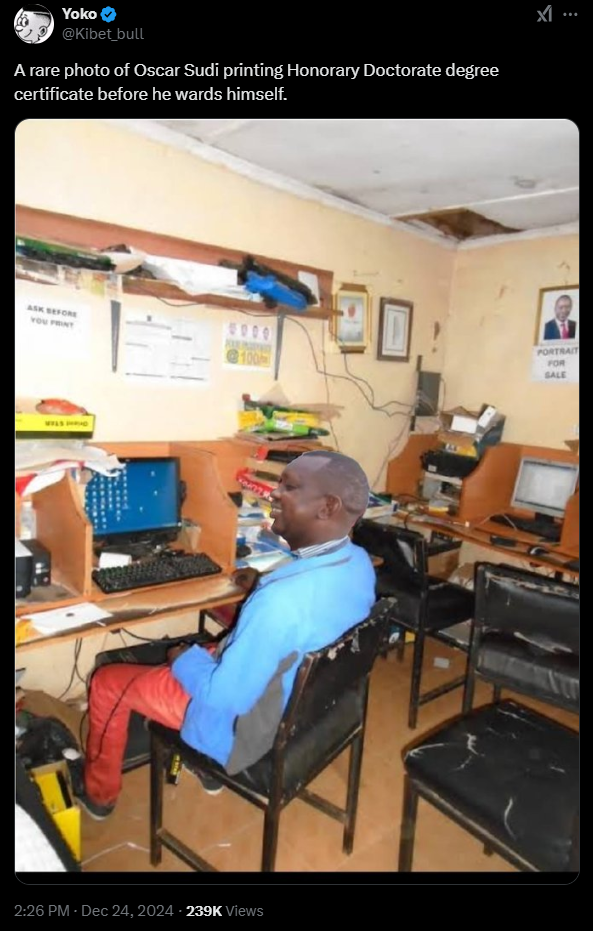

In the digital era, critiques are no longer limited to traditional formats like speeches or editorials. Kenya’s tech-savvy Gen Z, armed with tools like social media and visual symbolism, has weaponized satire and silhouettes to target political figures. This phenomenon underscores how ideas, not physical force, can challenge entrenched power.

However, this symbolic resistance has evoked sharp responses. Critics allege that the state or its affiliates resort to intimidation and suppression to quash dissent, highlighting the contested space where psychological and symbolic attacks meet authoritarian countermeasures.

Understanding the Impact of Words and Symbols

The debate over whether words and ideas cause harm akin to physical violence is not new. The impact of verbal or symbolic attacks often depends on context:

- Cultural Sensitivity: In Kenya’s sociopolitical landscape, deeply rooted traditions and values can amplify the perceived offense of symbolic acts.

- State Perception: For powerful institutions, public criticism and satire may undermine authority, leading to defensive or oppressive measures.

- Global Precedents: Historically, political expression—through speech, satire, or art—has been both a tool for change and a flashpoint for conflict. Examples range from African independence struggles to contemporary global movements like #MeToo.

The Missing Critics: Physical Retaliation to Psychological Offense?

The disappearance of individuals like Kibet Bull raises critical questions about state accountability and the right to dissent. Reports suggest that these individuals were involved in crafting or disseminating materials deemed offensive to the presidency. If confirmed, such actions reflect a troubling trend where psychological tactics are met with physical consequences.

- Legal Implications: Kenya’s constitution enshrines freedoms of speech and expression, yet these disappearances may signify a breach of these rights.

- Moral Dilemma: Does the state have the moral authority to use force against those who employ non-violent criticism, even if perceived as provocative or harmful?

A Call for Discourse

This scenario demands a broader societal conversation:

- Are words and images truly so threatening as to justify physical harm?

- How can Kenya reconcile the right to critique with the responsibility to uphold respect and unity?

- What safeguards can prevent the escalation from psychological warfare to physical suppression?

Kenya’s historical journey has often shown the resilience of its people in pushing for equity and justice. However, this chapter reminds us that the balance between freedom and security remains fragile. By addressing these issues openly and inclusively, Kenya can set a global example for handling dissent in a rapidly evolving digital age.