When it comes to history, the concept of authority holds immense importance. Authority, in this context, refers to the weight and reliability of the information presented. As we strive to understand the past, the credibility of the source plays a vital role in separating fact from fiction, particularly in cases where modern tools of historical investigation, such as carbon dating and extensive research methods, are absent.

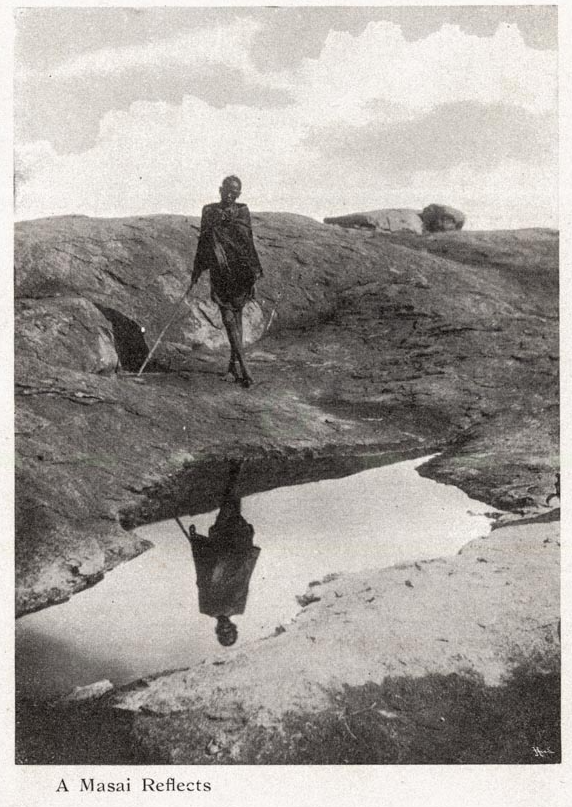

In societies where these tools were unavailable, authority often rested on observation and accumulated experience. Oral traditions, for instance, have long served as vital repositories of historical knowledge in many cultures. In such traditions, authority is typically attributed to elders who have observed and lived through significant periods of time. Their lived experience and insights are often viewed as invaluable for interpreting events and passing down history. However, age alone is not a definitive marker of authority. Instead, it is the depth of observation and understanding that truly lends weight to their narratives.

The Weight of Observation

An elder who has actively observed, engaged with, and reflected upon the details of their community’s history holds a stronger claim to authority than one who simply inherits the title of “elder.” This distinction is critical because authority derived without sufficient observation and engagement can lead to inaccuracies. Assumptions, biases, or even simple gaps in memory can distort the narratives passed down. This is why historical accuracy within oral traditions often depends on both the credibility of the storyteller and the rigor of the tradition in which the information is preserved.

For example, in African societies, oral traditions have preserved histories of kingdoms, migrations, and cultural practices for centuries. The storytellers, often known as griots, are respected for their detailed accounts. Their authority is built not only on their age but also on their dedication to preserving and recounting the intricate details of their people’s history. They undergo years of training, learning not just the stories but also the responsibility of maintaining their accuracy.

That said, the reliance on oral authority comes with its challenges. Memory is fallible, and over generations, even the most well-meaning recounting of events can be influenced by personal or cultural biases. This is where the value of corroboration comes into play. Communities that have thrived in oral traditions often cross-reference stories with those of neighboring groups or rely on rituals and symbols to maintain consistency.

What Authority Teaches Us Today

In modern historical studies, the role of authority has shifted with the advent of scientific methods and documentation. Carbon dating, for instance, provides an objective way to date artifacts, while archives and research tools offer a wealth of documented evidence. Yet, even with these advancements, the historian’s ability to critically evaluate sources remains paramount. The authority of a source—whether oral or written—must always be weighed against the evidence and context it provides.

Ultimately, authority in historical information is about trust, credibility, and evidence. Whether derived from oral traditions or modern research, it requires a commitment to observation, accuracy, and the rejection of unfounded assumptions. By valuing and scrutinizing authority, we ensure that history remains a tool for learning and reflection rather than one of distortion or manipulation.