The Maasai are one of East Africa’s most well-known indigenous communities, primarily residing in Kenya and Tanzania. Historically, they have been celebrated for their warrior culture, pastoralist economy, and deep connection to cattle, which have long defined their way of life. However, over the past two centuries, the Maasai have experienced profound transformations due to colonial land dispossession, internal conflicts, environmental changes, and modernization pressures.

By the 19th century, the Maasai controlled vast territories across Kenya and Tanzania, but a series of civil wars (Iloikop Wars), the Rinderpest epidemic, and British colonial expansion drastically reduced their land and power. The 1904 and 1911 treaties with the British forced them into reserves, permanently altering their nomadic lifestyle. Although independence in the 1960s offered hope for land reclamation, the new African governments prioritized agriculture over pastoralism, further pushing the Maasai to adapt to new economic realities.

In the 21st century, Maasai communities face new challenges, including land privatization, climate change, and competition with wildlife conservation efforts. As a result, many have begun transitioning from pure pastoralism to agro-pastoralism, integrating crop cultivation into their traditional economy. This shift, while economically beneficial for some, has environmental consequences, socio-cultural conflicts, and implications for wildlife conservation.

This article explores the historical evolution of the Maasai, from their origins and pre-colonial dominance to their struggles during the colonial period and their modern-day adaptation to farming. It examines how historical land dispossession, environmental changes, and government policies have shaped the Maasai’s current socio-economic landscape, highlighting the tension between tradition and modernity in their pursuit of survival.

Table of Contents

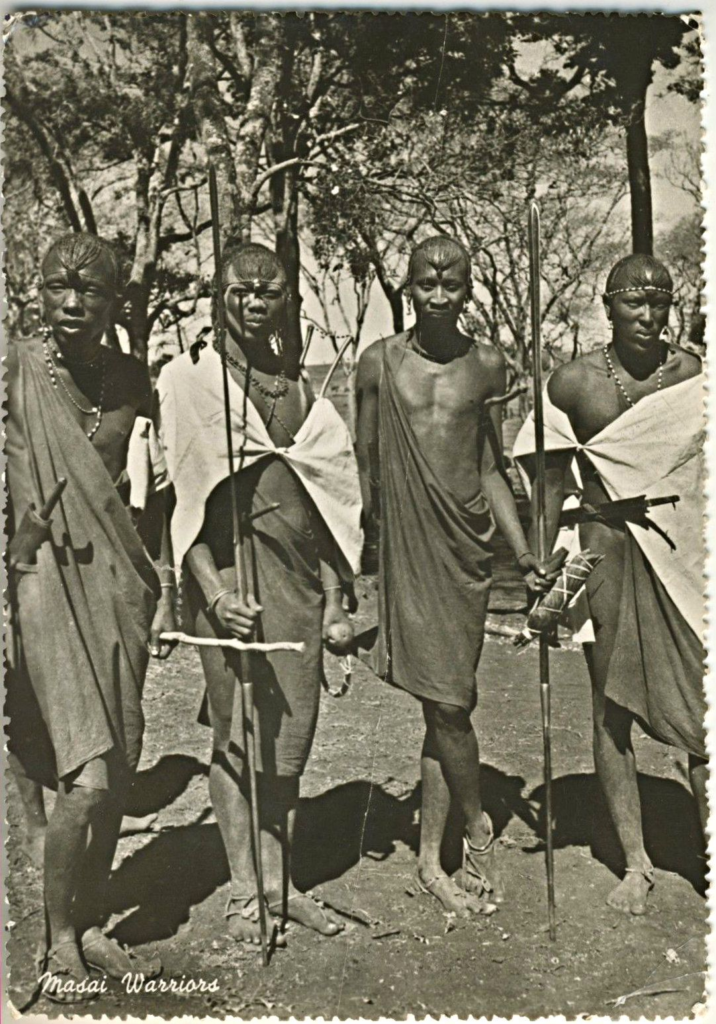

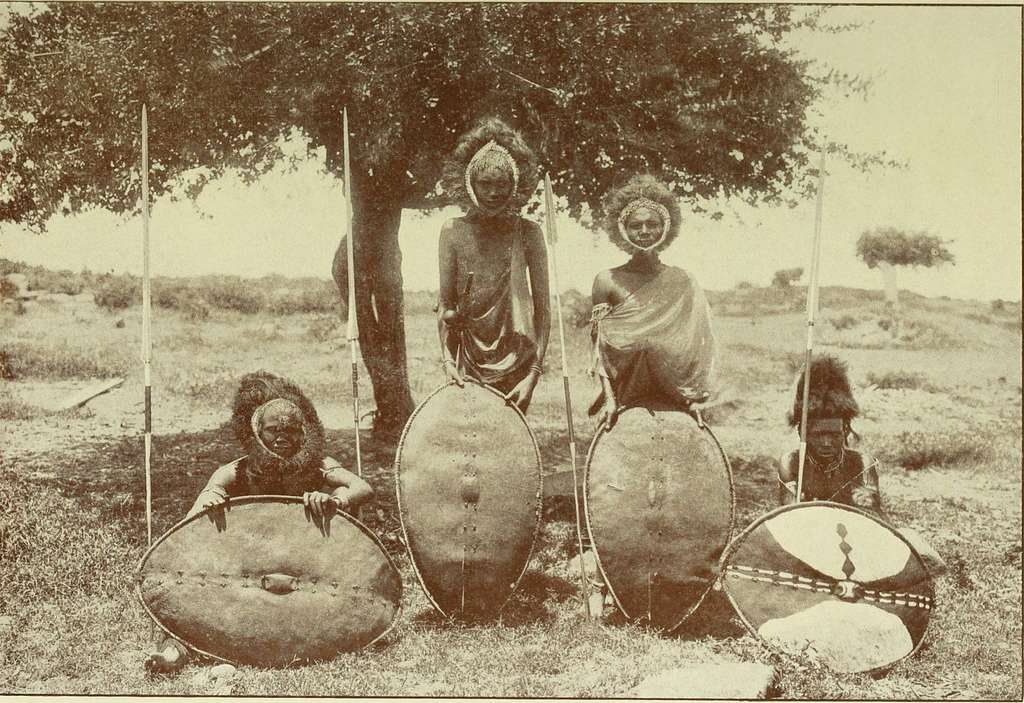

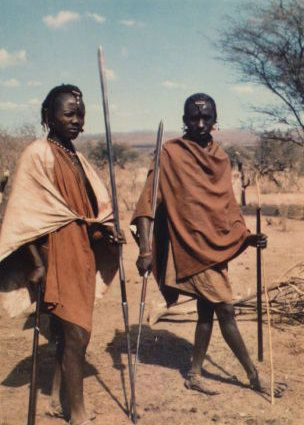

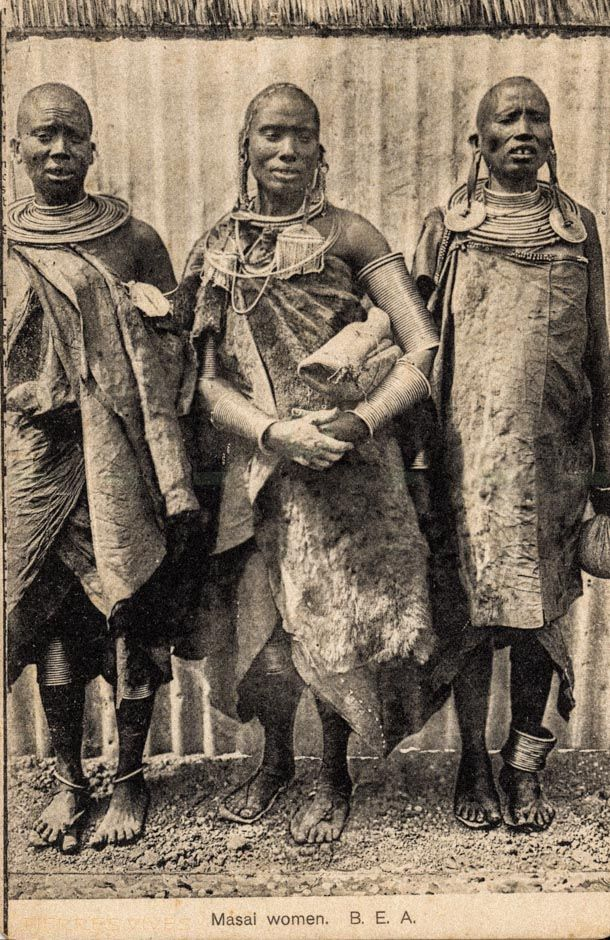

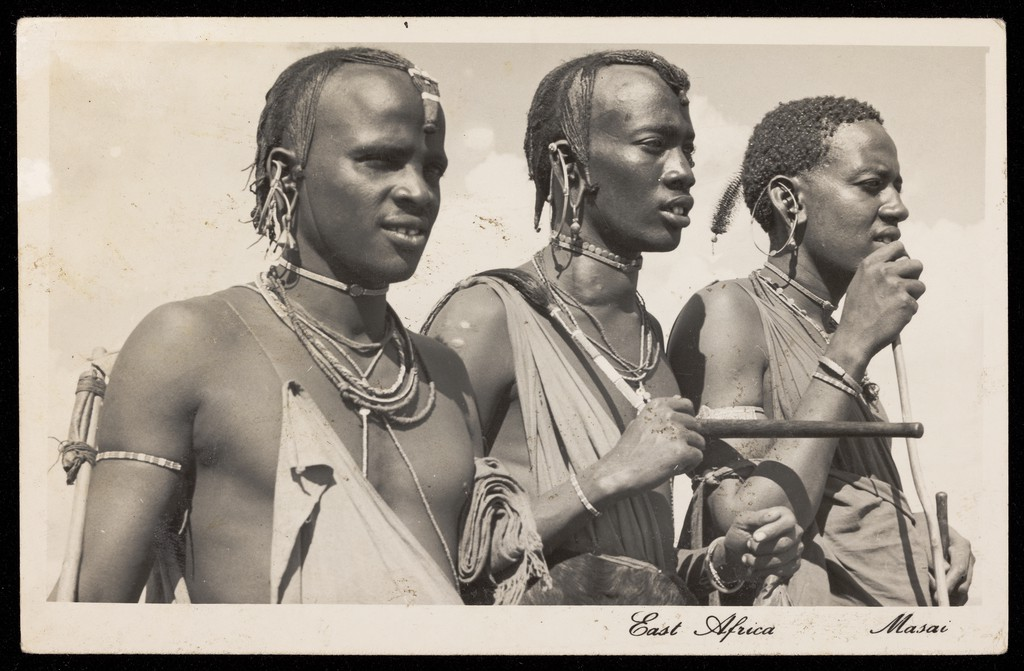

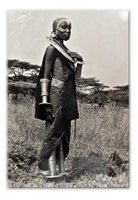

Maasai People in Pictures

Origins and Migration of the Maasai

The Maasai trace their origins to the Nile Valley region, with linguistic and historical evidence suggesting they migrated southward from present-day South Sudan. As part of the larger Nilotic migration, they moved into East Africa around the 15th century, gradually settling in the Rift Valley of present-day Kenya and Tanzania (Zeleza, 1995, p. 9).

Their migration was primarily driven by the search for better grazing lands for their cattle, which remain central to Maasai culture and economy. Along the way, they encountered various other ethnic groups, including the Kalenjin, Chagga, and Agikuyu (Kikuyu). Some of these groups were assimilated through intermarriage and cultural exchange, while others were displaced or engaged in conflicts over land and resources (Zeleza, 1995, p. 12).

By the early 19th century, the Maasai controlled an estimated 77,000 square miles of land, stretching from central Kenya to northern Tanzania. Their dominance, however, faced challenges, including internal conflicts, environmental pressures, and competition from neighboring groups. Despite these challenges, the Maasai remained a formidable force in the region until the arrival of European colonial powers in the late 19th century, which would dramatically alter their way of life (Zeleza, 1995, p. 15).

Oral Traditions and the Maasai View of Their Origins

Like many African communities, the Maasai rely on oral traditions to explain their origins, migrations, and way of life. These stories, passed down through generations by elders and spiritual leaders, serve as both historical records and moral lessons. While linguistic and archaeological evidence suggests a Nile Valley origin, the Maasai’s oral traditions emphasize divine intervention, ancestral wisdom, and their deep spiritual connection to cattle and land (Zeleza, 1995, p. 18).

One widely told Maasai legend describes how their ancestors discovered Maasailand. According to this story, the Maasai once lived in a dry and barren land, struggling to find enough pasture for their cattle. One day, they noticed a bird carrying a blade of fresh green grass in its beak, flying toward a distant cliff. The elders, interpreting this as a divine sign from Enkai, sent young warriors to climb the cliff and explore what lay beyond. They discovered a lush and fertile land, perfect for cattle grazing. However, as the Maasai climbed up, the ladder they used broke, leaving half of the people behind. Those who reached the top became the true Maasai, while those left below formed other communities (Zeleza, 1995, p. 21).

Another foundational oral tradition explains how the Maasai received their cattle. According to this story, the supreme god Enkai entrusted all the world’s cattle to the Maasai, making them the rightful guardians of these sacred animals. This belief reinforces their deep attachment to cattle and historically justified their raids on neighboring communities. In the Maasai worldview, taking cattle from other groups was not considered theft, but rather a restoration of what was divinely given to them (Zeleza, 1995, p. 23).

Beyond these origin stories, oral traditions also play a crucial role in shaping Maasai values, spiritual beliefs, and social practices. Elders use these narratives to educate the young on bravery, respect, and communal responsibility. Through songs, proverbs, and initiation rituals, the Maasai preserve their history without written records, ensuring that their identity and customs endure despite external pressures from modernization and globalization (Zeleza, 1995, p. 25).

Social Structure and Way of Life

The Maasai have a highly organized social structure that revolves around age-set systems, communal living, and their deep spiritual and economic connection to cattle. Their society is built on traditions that dictate social roles, responsibilities, and rites of passage from birth to elderhood. These customs have remained largely intact despite pressures from colonial rule and modernization.

1. The Age-Set System: From Youth to Elders

The Maasai social system is based on age-sets (olaji), which group men together based on their age and determine their responsibilities. Every Maasai male passes through several stages:

- Inkera (Children) – Boys and girls help with small household chores and tend young animals.

- Ilmoran (Warriors) – Around the age of 14-18, boys undergo circumcision (emorata) in a public ceremony, marking their transition into warriorhood. They leave their families and live in emanyatta (warrior camps), where they receive training in hunting, herding, and community defense.

- Junior Elders – After serving as warriors for about 15 years, the ilmoran transition into junior elderhood through a ceremony called eunoto. They begin settling down, marrying, and participating in decision-making.

- Senior Elders – This is the highest social rank. Senior elders (ilpayiani) are responsible for governance, resolving disputes, and conducting blessings and rituals.

The oloiboni (spiritual leader), a highly respected elder, plays a crucial role in Maasai society. He is believed to have the ability to communicate with Enkai, the Maasai god, and offers guidance, healing, and prophecies.

2. Role of Women in Maasai Society

While the Maasai age-set system applies mainly to men, women have significant roles within the community.

- Mothers and caregivers – Women take care of children, cook, build houses, and manage daily life in the enkang’ (homestead).

- Marriage and Polygamy – Marriage is arranged by elders, and polygamy is common. A man’s wealth is measured by his cattle and the number of wives he has. Women, however, have social networks among co-wives and maintain strong ties with their maternal families.

- Female Rites of Passage – Traditionally, Maasai girls underwent female circumcision (FGM) as a rite of passage into womanhood, though this practice is now widely discouraged due to modern health and human rights advocacy.

3. Cattle: The Heart of Maasai Life

Cattle are the foundation of the Maasai economy, social status, and spirituality. They provide milk, blood (used in ceremonies), meat, hides, and even currency for dowries and trade. A man’s wealth is judged by the size of his herd. Cattle also play a role in religious ceremonies, where elders offer prayers for fertility and prosperity.

4. Rituals, Songs, and Dance

Maasai ceremonies are filled with chanting, dancing, and blessings led by elders. Warriors are famous for their adumu, the “jumping dance,” performed during initiation rites and celebrations. These cultural expressions preserve Maasai identity and connect the younger generation to their traditions.

The Maasai’s social structure has helped them survive challenges like colonialism and land loss. However, modern pressures such as education, land privatization, and government policies are influencing their traditional way of life.

Maasai Conflicts with Neighboring Groups

Throughout their history, the Maasai have engaged in both cooperation and conflict with neighboring communities. As a pastoralist society, their way of life revolves around cattle, which often led to territorial disputes, cattle raids, and warfare with other groups. However, the Maasai also maintained important trade and cultural exchanges with some of these neighbors.

1. Relations with the Agikuyu (Kikuyu): Trade and Clashes

The Agikuyu, an agricultural community, were one of the Maasai’s closest neighbors in central Kenya. Their relationship was complex, marked by both trade and conflict. The Maasai exchanged cattle, hides, and milk with the Agikuyu for iron tools, gourds, and grains. However, due to their growing population and expansion into Maasai grazing lands, conflicts over land and resources arose.

One famous battle occurred in the late 19th century when the Maasai clashed with the Agikuyu over control of fertile lands near Mount Kenya. The Agikuyu adopted defensive strategies such as building fortified villages (mbari) and using poisoned arrows to counter Maasai raids. Despite these conflicts, intermarriage and cultural exchange between the two groups continued over time.

2. The Kalenjin and the Iloikop Wars (19th Century)

The Kalenjin, another Nilotic-speaking group, had a long history of interaction with the Maasai. They lived on the eastern side of Lake Victoria and competed for control of grazing lands. The most significant conflict between the two groups was during the Iloikop Wars of the 19th century.

The Iloikop Wars (1830s–1870s) were a series of internal Maasai conflicts that also involved other neighboring communities like the Kalenjin and Samburu. These wars were fought between different Maasai factions—the purely pastoralist Maasai and the Iloikop Maasai, who had adopted some agricultural practices. The wars ended with the defeat of the Iloikop faction, leading to the consolidation of Maasai power but also weakening them, making them vulnerable to European colonial forces later.

3. The Chagga and Peaceful Coexistence

The Chagga of northern Tanzania were one of the few groups that had little conflict with the Maasai. They were mainly farmers who lived on the slopes of Mount Kilimanjaro and did not compete for grazing lands. Instead, they maintained strong trading relationships with the Maasai, exchanging agricultural goods like bananas and grains for cattle and hides.

4. Clashes with the Akamba: Trade and Warfare

The Akamba, another Bantu-speaking community, were skilled hunters and traders who lived in what is now southeastern Kenya. Like the Agikuyu, they provided the Maasai with iron tools, baskets, and pottery in exchange for cattle. However, they also competed for access to trade routes and grazing lands, leading to periodic skirmishes.

5. Internal Conflicts: Warrior Rivalries and Cattle Raids

Beyond conflicts with other communities, the Maasai frequently fought among themselves, particularly between different age-sets and clans. Cattle raids (olbaa) were common, as young warriors sought to prove their bravery and increase their herds. These internal battles, while sometimes violent, were also part of the Maasai social system, reinforcing status and leadership within the warrior class.

Impact of These Conflicts

- Strengthened the Maasai’s reputation as fierce warriors.

- Created trade networks that helped sustain their economy.

- Led to territorial losses and changes in settlement patterns.

- Weakened the Maasai before the arrival of European colonial forces, making them more vulnerable to land dispossession.

Despite their history of warfare, the Maasai also demonstrated resilience and adaptability, forming alliances when necessary and maintaining their cultural identity through centuries of external pressures.

Epidemics, Rinderpest, and the 19th-Century Crisis

The late 19th century was one of the most devastating periods in Maasai history. A combination of civil wars, epidemics, and natural disasters nearly brought the community to collapse. The Maasai, once one of the most powerful groups in East Africa, lost much of their strength due to internal conflicts (Iloikop Wars), livestock diseases, human epidemics, and famine. These crises weakened the Maasai just as European colonial powers were beginning their expansion into the region.

1. The Iloikop Wars (1830s–1870s): Civil Wars Among the Maasai

Before external threats weakened them, the Maasai were already struggling with internal conflicts known as the Iloikop Wars. These wars were fought between different Maasai clans and age-sets over control of grazing lands, cattle, and leadership.

- The main division was between two factions:

- The Purko Maasai – Strictly pastoralist and dominant in southern Kenya and northern Tanzania.

- The Iloikop Maasai – More willing to engage in farming and trade.

- The wars weakened Maasai unity, and by the 1870s, the Purko faction emerged victorious. However, the prolonged fighting had already depleted resources, disrupted grazing patterns, and divided the Maasai, making them more vulnerable to external pressures.

2. The Rinderpest Epidemic (1890s): The Great Cattle Plague

Just after the Iloikop Wars ended, the Maasai faced a new disaster—the rinderpest epidemic, a highly contagious viral disease that killed over 90% of their cattle.

- Origins of Rinderpest:

- The disease likely entered East Africa from Ethiopia in the late 1880s, spreading rapidly through the region.

- By 1891, Maasailand was heavily affected.

- The disease killed not only cattle but also buffalo, wildebeest, and antelopes, disrupting the ecosystem.

- Impact on the Maasai:

- The Maasai relied almost entirely on cattle for food, trade, and social status. The loss of livestock led to widespread famine.

- Many Maasai were forced to abandon their pastoral lifestyle, moving to agricultural communities for survival.

- Some even sold themselves or their children into servitude to neighboring communities in exchange for food.

3. Human Epidemics: Smallpox and Famine

As if the rinderpest epidemic was not enough, a smallpox outbreak swept through Maasailand at the same time, killing thousands of people.

- The smallpox epidemic (1891–1893) spread rapidly due to Maasai mobility and interactions with traders and neighboring groups.

- Many weakened warriors and elders died, leaving the community even more vulnerable.

- With no cattle and declining population, the Maasai were left at one of their weakest points in history.

4. Environmental Disasters: Drought and Locust Invasions

During the same period, severe droughts and locust invasions further worsened the crisis.

- Drought (1897–1898) dried up rivers and reduced pastureland, leading to conflicts over water sources.

- Locust swarms destroyed any remaining vegetation, making it impossible to farm.

- The combination of war, disease, drought, and famine led to an estimated two-thirds decline in the Maasai population.

5. The Aftermath: Maasai Vulnerability to Colonial Rule

By the early 1900s, the Maasai had lost many of their warriors, cattle, and land. Their weakened state allowed the British colonial government to take control with minimal resistance.

- In 1904 and 1911, the British forced the Maasai to sign land agreements that pushed them into two reserves, losing about 60% of their land.

- The Maasai, once one of the most feared warrior groups in East Africa, were now under colonial control.

The Aftermath: Maasai Vulnerability to Colonial Rule

By the early 20th century, the Maasai were at their weakest point in history. Years of civil wars, devastating epidemics, environmental disasters, and famine had decimated their population and reduced their once vast cattle herds. The Maasai, who had once controlled large areas of Kenya and Tanzania, found themselves vulnerable to European colonial expansion. The British, recognizing their weakened state, took advantage of the situation to claim Maasai land for white settlers, drastically altering the Maasai way of life.

1. The 1904 and 1911 Land Agreements: Maasai Land Dispossession

As British colonial rule expanded across East Africa, the colonial government saw the fertile lands of Maasailand as prime land for European settlement and agriculture. The British forced the Maasai to sign two major agreements that pushed them out of their best grazing lands and confined them to much smaller areas.

- The 1904 Agreement

- The first Maasai land treaty was signed in 1904 between Maasai elders and the British.

- The Maasai were forced to give up the central highlands of Kenya, which had fertile grazing lands.

- In exchange, they were promised permanent settlement in two reserves:

- The Laikipia Reserve (north of the Rift Valley)

- The Southern Maasai Reserve (near the Tanzania border)

- The Maasai lost nearly half of their land in this agreement.

- The 1911 Agreement

- Seven years later, the British demanded even more land, violating the original agreement.

- The Maasai were forcibly evicted from the Laikipia Reserve and pushed further south.

- Most were moved to the Southern Maasai Reserve, an area that was drier and less suitable for large cattle herds.

- By this time, the Maasai had lost 60% of their ancestral land, and white settlers took over their best grazing areas.

- The Impact of the Land Loss

- The Maasai could no longer freely move their cattle to find the best grazing pastures.

- Many cattle died due to overcrowding in the reserves, leading to food shortages.

- The Maasai became more dependent on colonial authorities for survival.

- They lost control over major trade routes that had connected them to neighboring communities.

- Wealth and power shifted away from the Maasai elders, making it difficult for them to enforce traditional customs.

2. Maasai Resistance and Legal Battles

Not all Maasai accepted the land dispossession quietly. Some leaders, like Laibon Lenana and Chief Legalishu, attempted to negotiate with the British.

- Lenana and British Cooperation

- Laibon Lenana, the most influential Maasai spiritual leader at the time, chose to cooperate with the British rather than fight them.

- He believed that working with the British could help protect Maasai interests.

- The British used him to persuade other Maasai leaders to accept the treaties, further weakening Maasai resistance.

- Chief Legalishu and the Maasai Court Case (1913)

- Chief Legalishu, a Maasai leader in Laikipia, rejected the forced relocation and challenged the British.

- He led a legal battle, arguing that the British had violated the 1904 treaty by taking more land in 1911.

- The case went all the way to the British High Court, but the Maasai lost.

- The British dismissed the case, arguing that Maasai leaders had already agreed to the treaties.

- After this legal defeat, most Maasai had no choice but to relocate to the Southern Maasai Reserve.

3. Disruptions to the Maasai Way of Life

Losing their land had long-term effects on Maasai culture and traditions:

- End of Large-Scale Cattle Raiding

- Before colonial rule, Maasai warriors (ilmoran) raided cattle from neighboring communities.

- The British introduced laws banning cattle raids, making it harder for young warriors to prove their bravery.

- The age-set system, which depended on warrior culture, began to weaken.

- Colonial Taxes and Forced Labor

- The British introduced hut taxes and cattle taxes, forcing Maasai men to work in colonial farms and towns.

- Many Maasai had to sell their cattle to pay these taxes, further reducing their wealth and independence.

- Missionary Influence and Education

- Christian missionaries entered Maasailand and tried to change Maasai traditions, including polygamy and circumcision.

- Schools were built, but few Maasai families sent their children, fearing loss of cultural identity.

4. The Legacy of Land Dispossession

Even after Kenya and Tanzania gained independence in the 1960s, the Maasai never fully regained their lost lands.

- Much of the fertile land taken by the British was later controlled by Kenyan and Tanzanian governments, private farms, and national parks (e.g., Maasai Mara and Serengeti).

- Land privatization policies made it difficult for Maasai herders to access traditional grazing areas.

- Conflicts between wildlife conservation and Maasai pastoralism continue to this day, as national parks restrict Maasai herders from grazing in areas they historically used.

The 20th Century and the Road to Independence

After losing much of their land to British colonial rule in the early 1900s, the Maasai faced economic hardship, cultural disruption, and increasing political marginalization. Despite these challenges, they continued to adapt while maintaining their pastoralist traditions. As Kenya and Tanzania moved toward independence in the 1960s, the Maasai struggled to reclaim their rights in the new political landscape.

1. The Maasai Under British Colonial Rule (1920s–1950s)

By the 1920s, the Maasai had been pushed into two main reserves: the Southern Maasai Reserve (Kenya) and northern Tanzania. The British controlled their movements, banned cattle raiding, and introduced taxation, which forced many Maasai men to seek employment outside their communities.

Economic Changes and the Decline of Maasai Wealth

- With reduced grazing land, the Maasai could no longer sustain large cattle herds as they once did.

- The British imposed cattle taxes, forcing Maasai herders to sell livestock to pay the government.

- Some Maasai men took up low-paying jobs in settler farms and urban centers, marking the beginning of wage labor among the traditionally pastoralist community.

- Colonial veterinary services helped reduce cattle diseases like rinderpest, but government policies still favored white settler farms over Maasai herders.

Cultural and Social Disruptions

- Missionary influence increased, promoting Christianity and discouraging traditional Maasai practices such as polygamy and circumcision.

- Education was introduced, but very few Maasai children attended school. Many elders resisted education, fearing it would weaken Maasai identity.

- British authorities continued to undermine Maasai leadership, weakening the power of elders and spiritual leaders (oloiboni).

2. The Mau Mau Uprising and the Maasai’s Political Position (1952–1960)

During the Mau Mau rebellion (1952–1960), which was led by the Agikuyu (Kikuyu) against British rule, the Maasai largely remained neutral. Several factors contributed to this:

- Unlike the Kikuyu, the Maasai had not been heavily involved in colonial cash crop farming, so they did not share the same grievances.

- Many Maasai still held on to the promise made by the British in the 1904 and 1911 treaties that their land would be protected (even though it wasn’t).

- The British recruited Maasai warriors into the colonial police and military, using them to suppress the Mau Mau fighters.

However, the Mau Mau war accelerated Kenya’s independence movement, and by 1963, Kenya gained self-rule under Jomo Kenyatta. Tanzania (then Tanganyika) had already moved toward independence under Julius Nyerere in 1961.

3. Maasai in Post-Independence Kenya and Tanzania (1960s–1970s)

At independence, the Maasai hoped to reclaim their lost lands, but instead, they faced further political marginalization. The new African governments of Kenya and Tanzania focused on modernization and agriculture, often at the expense of pastoralist communities like the Maasai.

Land Policies and Continued Dispossession

- The Maasai expected Kenyatta’s government to honor their past agreements with the British, but this did not happen.

- Instead, much of the land taken by white settlers was given to Kikuyu farmers, not returned to the Maasai.

- National parks and wildlife reserves (e.g., Maasai Mara, Serengeti) were expanded, further limiting Maasai grazing land.

Villagization in Tanzania

- In the 1970s, Julius Nyerere introduced a policy called Ujamaa, a socialist program that encouraged collective farming.

- The Maasai were pressured to settle in villages and take up agriculture, despite their traditional nomadic lifestyle.

- Many resisted, but government intervention forced some Maasai into farming and wage labor.

The Shift to Farming Among the Maasai: A New Trend

For centuries, the Maasai were known for their strictly pastoralist lifestyle, relying on cattle as their main source of food, wealth, and social status. However, in recent decades, economic pressures, land privatization, and environmental challenges have forced many Maasai to adopt farming as a survival strategy. This shift to agriculture has become a growing trend, particularly in areas such as Kajiado, Narok, and Loitokitok, where irrigated farming is replacing traditional pastoralism【Okello & D’Amour, 2008】.

1. Factors Driving the Shift to Agriculture

a) Land Privatization and Subdivision

- Traditionally, the Maasai practiced communal land ownership, allowing their cattle to move freely across large grazing lands.

- However, after Kenya’s independence (1963), government policies encouraged land privatization, leading to the subdivision of group ranches into individual plots.

- Many Maasai sold their land or leased it to farmers, reducing access to communal grazing areas【Seno & Shaw, 2002】.

b) Decline of Pastoralism

- Droughts and climate change have made it harder to sustain large herds of cattle, as water sources dry up and pastures shrink【Thompson & Homewood, 2002】.

- Livestock diseases and high veterinary costs have also contributed to the decline of pastoralism【Bourn & Blench, 1999】.

- As a result, many Maasai have begun farming as an alternative source of food and income.

c) Economic Pressures and Market Expansion

- The collapse of the livestock economy in the late 20th century made it difficult for pastoralists to earn a living.

- Agriculture provides a more stable source of income, especially with growing local markets in Kimana, Loitokitok, and Nairobi【Campbell et al., 2000】.

- Some Maasai lease their land to commercial farmers, who have more experience in irrigation farming【Seno & Shaw, 2002】.

2. The Rise of Irrigated Agriculture in Maasailand

a) Growth of Farming Near Amboseli National Park

- In Kimana and Namelok near Amboseli, irrigated farming has expanded rapidly, fueled by electric fencing projects designed to reduce human-wildlife conflicts【Okello & D’Amour, 2008】.

- Farming along riverbanks is common, but it has led to declining water levels downstream, affecting both livestock and wildlife.

b) Crops Grown by the Maasai

- Many Maasai now grow maize, tomatoes, onions, beans, and vegetables for both subsistence and sale【Okello, 2005】.

- Irrigation allows for year-round farming, making agriculture more profitable than livestock keeping in some areas.

c) Land Leasing to Outsiders

- Some Maasai lease their land to non-Maasai farmers, who have better farming knowledge and equipment.

- This has led to land ownership disputes and concerns over loss of Maasai identity【Seno & Shaw, 2002】.

3. Challenges of Agricultural Expansion

a) Environmental Degradation

- Deforestation and soil erosion have increased due to land clearing for farms【Okello & D’Amour, 2008】.

- The heavy use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides has polluted water sources and soil【Barrow et al., 1993】.

- Overuse of river water for irrigation is reducing water availability for livestock and wildlife, worsening human-wildlife conflicts.

b) Conflicts with Wildlife

- Amboseli National Park and Maasai Mara were once open grazing lands, but now fencing and farming have blocked wildlife migration routes.

- Elephants and other wild animals often raid Maasai farms, leading to increased conflicts between farmers and conservationists【Okello, 2005】.

c) Cultural and Social Tensions

- Many Maasai elders oppose farming, seeing it as a loss of traditional identity.

- Younger generations, however, embrace agriculture as a way to adapt to modern economic challenges.

- Disputes arise between those who sell land for farming and those who want to preserve pastoralism.

4. The Future of Maasai Agriculture

Government and NGO projects are promoting agro-pastoralism, which combines small-scale farming with cattle herding to ensure food security while maintaining Maasai traditions.

The debate over farming vs. pastoralism continues in Maasailand. While agriculture provides economic opportunities, it also threatens the traditional Maasai way of life.

Conservation efforts are pushing for sustainable farming practices that balance agriculture, pastoralism, and wildlife conservation【Okello & D’Amour, 2008】.

Reference List

Books & Journal Articles

- Bourn, D., & Blench, R. (1999). Can Livestock and Wildlife Coexist? An Interdisciplinary Approach to the Management of Conservation Areas in Africa. Overseas Development Institute.

- Campbell, D. J., Gichohi, H., Mwangi, A., & Chege, L. (2000). Land Use Conflict in Kajiado District, Kenya. Land Degradation & Development, 11(3), 285-293.

- Campbell, D. J., Lusch, D. P., Smucker, T. A., & Wangui, E. E. (2003). Root causes of land use change in the Loitokitok area of Kenya: Land tenure, population dynamics and environmental change. Land Use Policy, 20(3), 321-331.

- Galaty, J. G. (1992). The Land Is Yours: Social and Economic Change Among the Maasai of Kenya.

- Githaiga, J. M., Reid, R. S., Muchiru, A. N., & van den Berg, L. (2003). The Influence of Settlement and Pastoralism on Vegetation and Wildlife in Kenya’s Savanna Ecosystem. African Journal of Ecology, 41(4), 328-337.

- Lindenmayer, D. B., & Nix, H. A. (1993). Ecological Principles for the Design of Wildlife Corridors. Conservation Biology, 7(4), 627-630.

- Newmark, W. D. (1993). The Role and Design of Wildlife Corridors with Examples from Tanzania. Ambio, 22(8), 500-504.

- Okello, M. M. (2005). Land Use Changes and Human–Wildlife Conflicts in Amboseli Area, Kenya. Human Dimensions of Wildlife, 10(1), 19-28.

- Okello, M. M., & Kiringe, J. W. (2004). Threats to Biodiversity and Their Implications in Protected and Adjacent Dispersal Areas of Kenya: Case Study of Amboseli Ecosystem. Biodiversity & Conservation, 13(6), 1039-1056.

- Okello, M. M., & D’Amour, D. E. (2008). Agricultural Expansion Within Kimana Electric Fences and Implications for Natural Resource Conservation Around Amboseli National Park, Kenya. Journal of Arid Environments, 72(12), 2179-2192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jaridenv.2008.07.008

- Seno, S. K., & Shaw, W. W. (2002). Land Tenure Policies and Wildlife Conservation in Kenya. Conservation Biology, 16(4), 1036-1046.

- Sindiga, I. (1995). Wildlife-Based Tourism in Kenya: Land Use Conflicts and Government Compensation Policies Over Protected Areas. Journal of Tourism Studies, 6(2), 45-55.

- Thompson, M., & Homewood, K. (2002). Entrepreneurs, Elites, and Exclusion in Maasailand: Trends in Wildlife Conservation and Pastoralist Development. Human Ecology, 30(1), 107-138.

- Western, D. (1975). Water Availability and Its Influence on the Structure and Dynamics of a Savanna Large Mammal Community. African Journal of Ecology, 13(3-4), 265-286.

- Western, D. (1982). The Environment and Ecology of Pastoralists in Arid Savannas. Development and Change, 13(2), 183-211.

- Worden, J., Reid, R. S., & Gichohi, H. (2003). Land-Use Impacts on Large Wildlife and Livestock in the Kenya-Tanzania Borderland. Biological Conservation, 114(2), 271-286.

- Young, T. P., & McClanahan, T. R. (1996). Conservation Biology in Kenya: What Role for Science? Conservation Biology, 10(2), 539-542.

Footnotes

- Oral traditions suggest that the Maasai migrated from the Nile Valley region, with historical and linguistic evidence supporting this theory【Galaty, 1992】.

- By the early 19th century, Maasailand stretched over 77,000 square miles before British colonial expansion reduced it significantly【Sindiga, 1995】.

- The Maasai relied on age-sets, with warriors (ilmoran) protecting the community and elders (ilpayiani) making decisions【Campbell et al., 2000】.

- The Iloikop Wars (1830s–1870s) weakened the Maasai before the arrival of European colonizers【Galaty, 1992】.

- The Rinderpest epidemic (1890s) killed over 90% of Maasai cattle, leading to famine and social collapse【Western, 1982】.

- The 1904 and 1911 Maasai land treaties resulted in the loss of over 60% of Maasai land to British settlers【Seno & Shaw, 2002】.

- Some Maasai leaders, like Chief Legalishu, resisted colonial land dispossession but were unsuccessful【Sindiga, 1995】.

- After independence in 1963 (Kenya) and 1961 (Tanzania), the Maasai hoped to reclaim land, but government policies favored agriculture over pastoralism【Thompson & Homewood, 2002】.

- In the 1970s, the Ujamaa socialist policy in Tanzania encouraged farming, forcing many Maasai into agriculture【Campbell et al., 2003】.

- By the 21st century, over 71% of Maasai herders in Kajiado District had attempted crop cultivation due to land subdivision and economic pressures【Okello, 2005】.

- Electric fencing in Kimana and Namelok was introduced to reduce human-wildlife conflict, but poor maintenance has led to increased tensions【Okello & D’Amour, 2008】.

- Agriculture consumes 400% more water than livestock and human consumption combined, leading to water shortages and environmental degradation【Barrow et al., 1993】.

- The Maasai now grow maize, onions, tomatoes, and beans for both subsistence and commercial sale【Okello & D’Amour, 2008】.

- Some Maasai lease land to outsiders who have more farming experience, leading to conflicts over land rights and traditional ownership【Seno & Shaw, 2002】.

- Despite economic benefits, environmental concerns such as soil erosion, deforestation, and pesticide pollution threaten the sustainability of farming in Maasailand【Okello & D’Amour, 2008】.