Early Life and Education

Dedan Kimathi Waciuri was born in October 1920 in Thenge (sometimes spelled Kanyinya) village of Tetu, Nyeri District in central Kenya. Raised in a peasant Kikuyu family under colonial rule, young Kimathi grew up witnessing the profound inequalities imposed by British settler domination – from African land dispossession to harsh labor demands. Despite these hardships, his father valued education and sent Kimathi to local mission schools. Kimathi proved an able student, known for his sharp writing and oratory skills, but also for a rebellious streak; teachers found him fiercely competitive and even unruly at times. His schooling was cut short, however, by the limited opportunities colonial policies afforded Africans. Like many of his generation, Kimathi’s formal education ended after a few years as colonial authorities discouraged African advancement (the 1949 Beecher Report, for example, capped most Africans’ schooling at elementary levels to keep them as laborers).

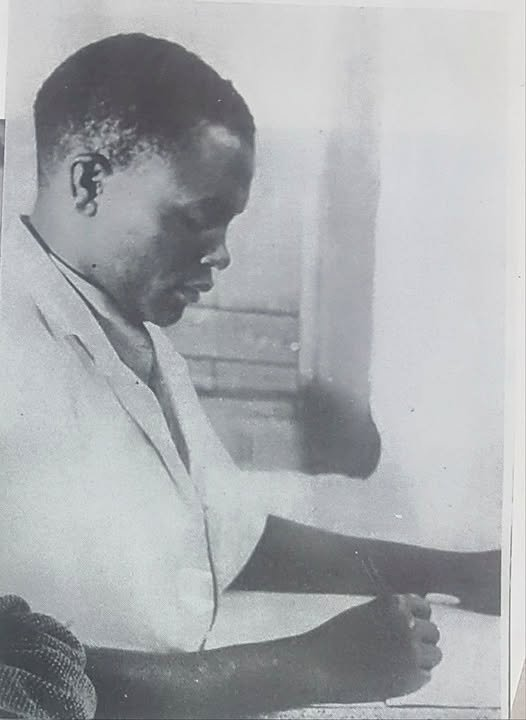

In 1941, with World War II raging, Kimathi briefly enlisted in the British colonial army (King’s African Rifles) as a low-ranking support worker. He was assigned the humble role of a sweeper, and this experience exposed him to the degrading treatment of African recruits. He deserted soon after, reportedly in disgust at the stark racial discrimination African soldiers endured. Back in civilian life, Kimathi eked out a living doing odd jobs – from herding livestock to clerical work. By the late 1940s he managed to secure a position as an untrained primary school teacher. Teaching gave him a small taste of leadership and community respect. It also honed his communication skills, as he was responsible for instilling basic literacy and nationalist awareness in young Kenyans. However, he lost the post amid accusations of instilling indiscipline (and possibly for physically disciplining pupils too harshly, as some accounts suggest).

These early experiences shaped Kimathi’s outlook. He had learned to read and write English – a “miracle” for a peasant’s son in those days – and became an avid reader of newspapers and political tracts. He also grew resentful of colonial injustices. By the late 1940s, Kenya’s nascent African nationalist movement was on the rise, especially among veterans and educated youths returning from the war. Kimathi gravitated toward this ferment. In 1947 he moved to the settler-dominated Rift Valley area (Ol Kalou) for work, and there he joined the Kenya African Union (KAU), Kenya’s first nationwide African political party. As a KAU activist, he sharpened his political awareness – attending rallies, debating grievances like land alienation and the racist kipande pass laws, and witnessing crackdowns on peaceful protest. This period was Kimathi’s road to radicalization: he concluded that polite petitions and meetings alone would not loosen colonialism’s shackles.

Road to Radicalisation and Political Awakening

Kimathi’s political awakening accelerated through the early 1950s as Kenya edged toward open revolt. While in the Ol Kalou KAU branch, he emerged as a bold organizer. By 1950 he was serving as branch secretary of KAU in the area. Crucially, this branch (dominated by militant younger activists rather than moderate older leaders) was secretly involved in administering the oath of unity that bound members to the underground movement later known as Mau Mau. Kimathi deeply believed in the power of oathing to cement loyalty for the freedom struggle. He personally presided over many oath ceremonies – nights where small groups of recruits swore fierce loyalty to the cause of Land and Freedom. The oath, often sealed with blood symbolism, was meant to unite disparate individuals into a sworn brotherhood against colonialism. Kimathi enforced these rituals strictly, even meting out beatings to those who wavered, as he felt only total unity and discipline could overcome the British Empire.

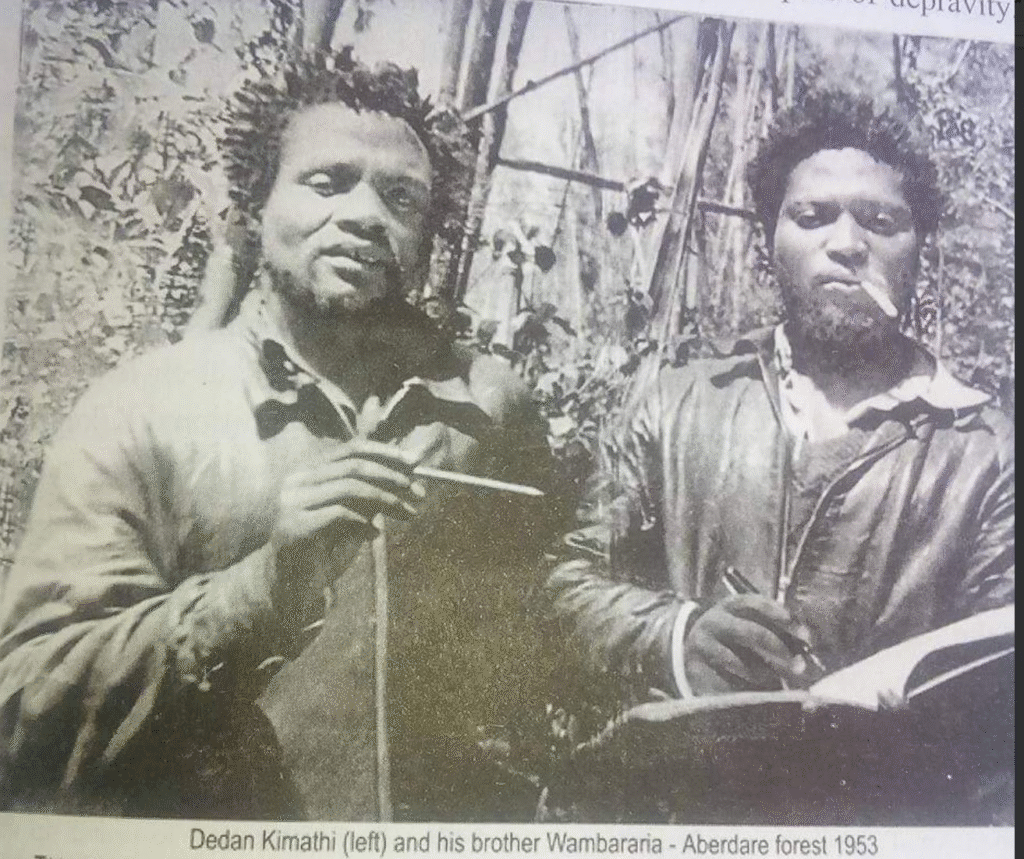

By 1951, the colonial authorities had identified Kimathi as a troublemaker. He was briefly arrested for his underground activities, but impressively escaped custody with the help of sympathizers in the police. This daring escape into hiding marked a turning point – Kimathi decided to go “fully underground.” He linked up with like-minded militants in Nairobi and central Kenya who were stockpiling weapons and mobilizing fighters. In October 1952, the colonial government declared a State of Emergency in response to increasing acts of sabotage and assassinations of loyalist chiefs by Mau Mau guerrillas. The crackdown was swift: nationalist moderates like Jomo Kenyatta were arrested, leaving militants like Kimathi to take the helm of resistance. Kimathi fled to the forests of Aberdare and Mt. Kenya, where hundreds of young Kikuyu, Embu, and Meru fighters were assembling guerrilla bands rather than submit to mass detention.

In the forest, Kimathi’s radicalization translated into armed leadership. He helped form the Kenya Land and Freedom Army (KLFA) – the militant wing of the uprising that the British derogatorily labeled “Mau Mau.” Kimathi quickly rose to prominence as one of its boldest leaders. In 1953, he was a key architect of the Kenya Defence Council, a body created to coordinate all the disparate guerrilla units hiding in the mountains. This was effectively the high command of the Mau Mau revolt, and Kimathi, by virtue of his charisma and organizing ability, became its de facto head. As Field Marshal of the KLFA, he oversaw strategy, camps, and supply lines for fighters across the Mt. Kenya and Aberdare ranges. His early political grooming in KAU and the oath societies had prepared him well: he combined political vision with military acumen. Fellow fighter Karari Njama later recounted that Kimathi emphasized keeping records of the guerrillas’ activities and decisions – an almost prophetic sense that their struggle’s history needed to be preserved. Indeed, Kimathi saw the Mau Mau war not as banditry (as the British claimed) but as the legitimate Kenyan War of Independence, a chapter of history worth recording.

Did you know? Historian Shiraz Durrani notes that in 1954 the forest fighters even convened a “Kenya Parliament” in the Aberdares and declared Kimathi as the movement’s Prime Minister, underscoring the rebels’ aim to form a proto-government of a free Kenya. This speaks to Kimathi’s ideological evolution – he was no longer just a guerrilla bandit in the woods, but a statesman-in-arms envisioning a liberated nation. As Durrani argues, the Mau Mau rebellion under Kimathi’s militant leadership was in truth Kenya’s War of Independence, a concerted anti-colonial uprising with clear political aims, not a random tribal revolt

Role in the Mau Mau Movement

Kimathi’s role in the Mau Mau uprising was pivotal – he was both military commander and inspirational figurehead for the insurgency. In the thick forests of Mt. Kenya and the Aberdares, he helped transform disorganized bands of fighters into a more structured guerrilla army. Field Marshal Kimathi co-ordinated multiple regional units that had sprung up after 1952. He worked alongside other forest generals – men like Stanley Mathenge (leader of the Nyeri sector Itūma wa Ndemi battalion), General China (Waruhiu Itote) in Mount Kenya, and others – but Kimathi was widely recognized as the overall leader of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army. Under his leadership, a Kenya Defence Council (sometimes called War Council) was established in 1953 to unify strategy. By mid-1954, a landmark gathering known as the “Kenya Parliament” was held deep in the forest to assert a unified command. It was here that Kimathi was reportedly declared “Prime Minister” of the provisional government of Kenya – an audacious bid to declare legitimacy against the colonial regime.

On the battlefield, Kimathi provided strategic direction. He advocated for classic guerrilla tactics – hit-and-run raids on settler farms and colonial outposts, seizure of weapons, and sabotage of colonial infrastructure. Mau Mau fighters under Kimathi’s command were relatively few (at peak perhaps 10–15 thousand active fighters), but they had intimate knowledge of the terrain and support from local peasants. Kimathi ensured that fighters struck at night or dawn, melting back into the jungle to avoid pitched battles with better-armed British troops. This kept the colonial forces off-balance for a time. He also enforced a strict code of conduct via the oath: fighters had to remain loyal and were forbidden from criminal acts against fellow Africans (though inevitably, some rogue elements called “komerera” engaged in banditry, which Kimathi tried to curb).

One of Kimathi’s most important roles was sustaining morale and unity. In the brutal conditions of forest warfare – short on food, facing cold and constant danger – his leadership kept the disparate groups from disintegrating. He was known to carry a Bible and often invoked both traditional and Christian motifs to inspire fighters. Kimathi’s dreadlocked hair and charismatic oratory gave him an almost prophetic aura among the fighters, many of whom saw him as the spiritual embodiment of the resistance. According to oral testimonies, Kimathi would remind his troops that they fought not just for themselves but for the generations to come, to reclaim the land stolen since the turn of the century. Such exhortations imbued the guerrillas with a sense of higher purpose.

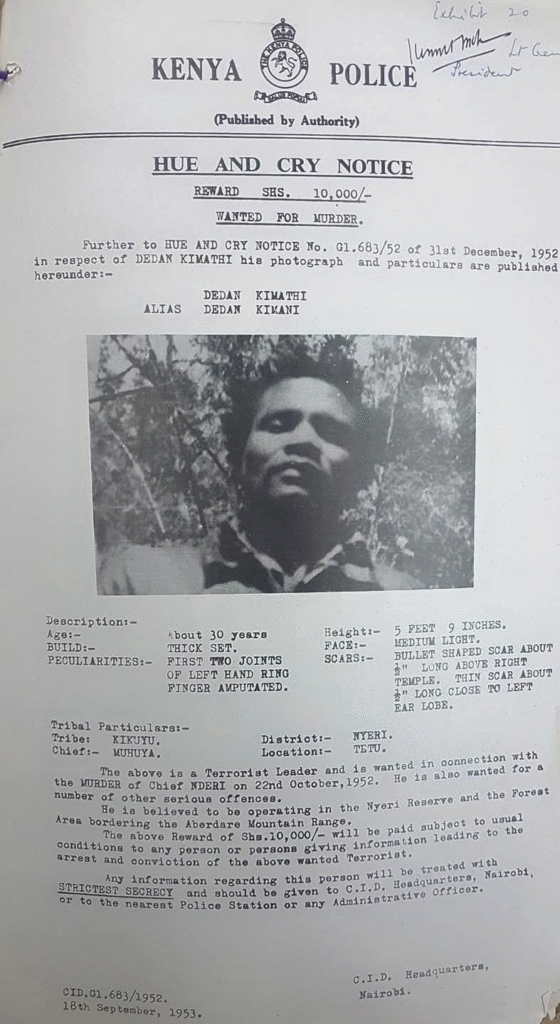

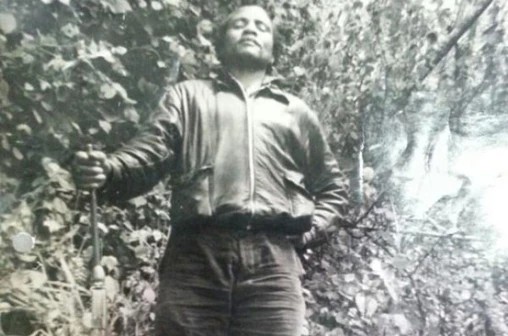

Kimathi also used psychological warfare effectively. In a famous incident, learning that colonial authorities had no photograph of him (their most wanted man), Kimathi sent them a studio portrait of himself – bedecked in his dreadlocks and military regalia. This act was both taunt and propaganda: he was declaring that the colonial government could not hide his image or his cause from the public. British forces distributed “Wanted” posters with that portrait, inadvertently turning Kimathi into a legend. Indeed, British propaganda demonized him as the face of Mau Mau terror – a “scar-faced schoolteacher turned gang leader,” as one 1950s press piece described him. But among Africans, counter-narratives spread portraying Kimathi as a Robin Hood figure fighting for rightful land and freedom.

By late 1953, the war intensified and British reinforcements poured in (over 50,000 troops and police). Kimathi’s fighters were outgunned and increasingly cornered by aggressive counter-insurgency: “Operation Anvil” in 1954 purged Mau Mau sympathizers from Nairobi, and collective punishment in the Kikuyu reserves (including detention camps and “emergency villages”) cut off guerrilla supplies. Kimathi attempted a bold initiative in this period: he wrote to the British proposing a truce. In a September 1953 letter he sent from the Aberdare forest, Kimathi pleaded, “It is only peace we want. We cannot live without food. If the police and soldiers are withdrawn, the fighting will stop at once.”. General George Erskine, the British commander, responded by air-dropping leaflets urging Mau Mau to surrender, promising fair treatment. However, white settler intransigence led the government to refuse any amnesty, and Kimathi’s overture was ultimately rebuffed. The war went on, more vicious than before.

By 1955–56, the Mau Mau movement was faltering – many fighters were killed or captured, and some leaders like General China had been caught and even tried to persuade others to surrender. Kimathi, however, remained in the forest redoubt, unwilling to give up. He reportedly said he would “rather die on my feet than live on my knees,” capturing his refusal to surrender.. His persistence kept a flicker of resistance alive even as the odds grew hopeless. In essence, Kimathi’s role was to personify unyielding resistance. As historian Wunyabari Maloba notes, Mau Mau was fundamentally a nationalist peasant revolt, and without leaders like Kimathi the sustained revolt would not have been possible. He gave Mau Mau a unifying voice and face.

Leadership Style and Ideological Vision

Kimathi’s leadership style was a blend of strict discipline, personal bravery, and visionary fervor. Discipline was paramount: he enforced the fighters’ oath rigorously and was harsh toward betrayal or desertion. As a Field Marshal, Kimathi could be severe – ordering the execution of confirmed informers and traitors to protect the movement. Yet surviving Mau Mau veterans also describe him as having a charismatic, inspirational presence. He led from the front, often personally participating in risky missions and enduring the same hardships as ordinary fighters (living off wild roots and berries, constantly on the move to evade patrols). This earned him immense respect and loyalty. “Kimathi’s tactical brilliance, honed during World War II, transformed the Mau Mau into a powerful force,” one account reflects (perhaps overstating his WWII experience, but underscoring how fighters viewed his acumen). He was adept at outwitting colonial forces, using decoys and intelligence networks among villagers to stay one step ahead.

Importantly, Kimathi possessed a far-sighted ideological vision beyond the immediate war. He consistently articulated that the struggle was not about random violence but about fundamental issues – land, freedom, and dignity. He decried how the British had stolen fertile African lands for settler farms and forced Kikuyu families into crowded “reserve” areas. He spoke of a Kenya where people could live freely on their ancestral soil and prosper without oppression. In his forest camp speeches and writings, Kimathi emphasized unity across ethnic lines – noting that the Kikuyu, Embu, Meru (and indeed any Kenyan who suffered colonialism) shared a common cause. This was significant because colonial propaganda tried to paint Mau Mau as an exclusively Kikuyu tribal madness. Kimathi instead cast it as a national liberation war. Under his leadership, fighters from multiple communities cooperated, and even some Luo and Kamba sympathizers in the cities aided the cause. His ability to transcend ethnic divisions for a greater goal was a hallmark of his leadership.

Kimathi was also surprisingly intellectual for a guerrilla leader with limited formal schooling. He maintained diaries during the forest war – scribbling notes, plans, even poetry, by the light of hidden campfires. These writings (later recovered and published) reveal a man who contemplated Kenya’s future deeply. In his diary, Kimathi envisioned a free Kenya that would be just and equal for all tribes and classes. He wrote about the need for education and economic opportunity for the peasantry once independence was won. He also reflected on the importance of international solidarity; though Mau Mau got little external help, Kimathi admired other anti-colonial struggles worldwide and hoped Kenya’s fight would spark broader African liberation. Justice, equality, and African self-determination were themes he returned to often. One diary entry speaks of “the upliftment of all Kenyans, irrespective of their tribe or social status,” underscoring his rejection of both colonial racism and internal tribalism.

His correspondence and messages during the war likewise show ideological clarity. For instance, when colonial authorities tried to dismiss Mau Mau as mere savagery, Kimathi countered with propaganda of his own: he issued “press releases” from the forest via intermediaries, declaring Mau Mau’s political aims. In one such statement he proclaimed that British imperialism was the enemy, not white people per se, and that the movement’s fight was against colonial oppression and for African land rights. Such pronouncements, documented by historians, reflect that Kimathi saw Mau Mau as part of a wider anti-imperialist struggle, not a nihilistic campaign. Indeed, Shiraz Durrani notes that Mau Mau’s ideology under Kimathi linked economic grievances (land, wages) with political demands (self-rule), aligning with radical trade unionism of the time. Kimathi’s personal interactions also demonstrated ideological savvy – for example, while awaiting trial he engaged a Catholic priest, Father Marino, in discussions about religion and freedom, cleverly steering conversations to avoid self-incrimination while affirming his convictions【13†P288-P289】.

Despite the harsh bush conditions, Kimathi insisted on some semblance of governance and order in liberated zones. He encouraged creation of civilian committees in forest-adjacent villages to secretly supply the fighters and administer loyalty oaths among the populace – a rudimentary “shadow government” under the nose of the British. In liberated pockets, Mau Mau fighters would sometimes redistribute seized food to needy villagers, a policy Kimathi approved to maintain popular support. All this speaks to an early form of revolutionary leadership that went beyond combat. In Kimathi’s own words (as remembered by compatriots), “We are not thugs; we are an army of freedom. Our struggle is just.” This principled stance, even as atrocities and reprisals mounted on both sides, set Kimathi apart. He became the living symbol of the Mau Mau ideology of resistance. No wonder Nelson Mandela, years later, would praise Kimathi and his comrades for inspiring South African freedom fighters.

Capture, Trial, and Execution

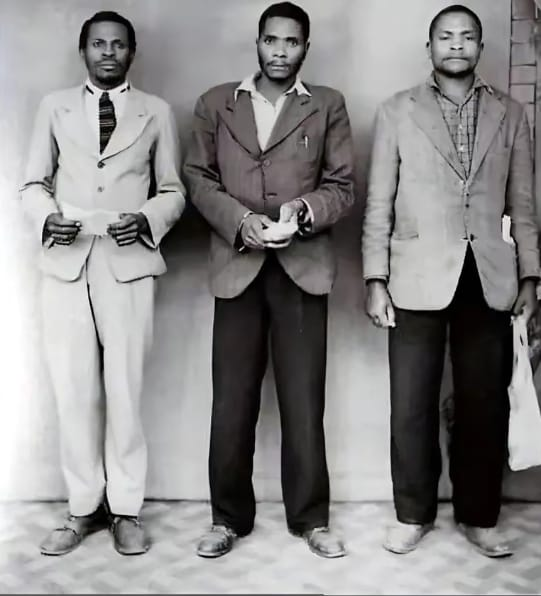

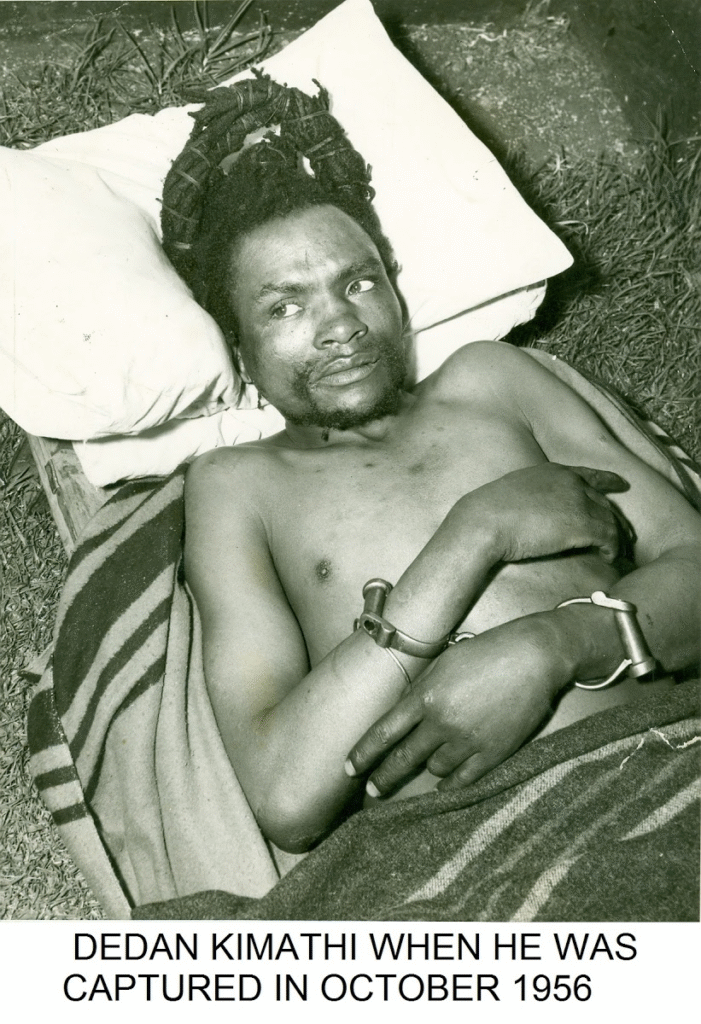

By 1956, after four grueling years of guerrilla war, the British intensified efforts to hunt down Kimathi – whom they saw as the linchpin of the dwindling rebellion. The task fell to the notorious colonial officer Ian Henderson (nicknamed the “Mau Mau hunter”), who had made it his personal mission to capture Kimathi. Acting on intelligence and helped by trackers and turncoat informers, British patrols closed in. In the early hours of October 21, 1956, Dedan Kimathi’s luck ran out. The exact circumstances of his capture remain a bit contested – some say a former fighter betrayed his whereabouts, others that he was spotted by chance. The recorded version is that Kimathi, clad in a brown jungle jacket and armed with a .38 caliber revolver, was shot in the leg by a tribal policeman named Ndirangu Mau as Kimathi attempted to leap across a trench near his forest hideout. Wounded and unable to run, Kimathi was surrounded and arrested. A famous photograph soon after shows him on a stretcher, conscious but grimacing, his long dreadlocks sprawled – the mighty Field Marshal fallen. The British exulted; his capture, they knew, symbolically marked the end of organized Mau Mau resistance.

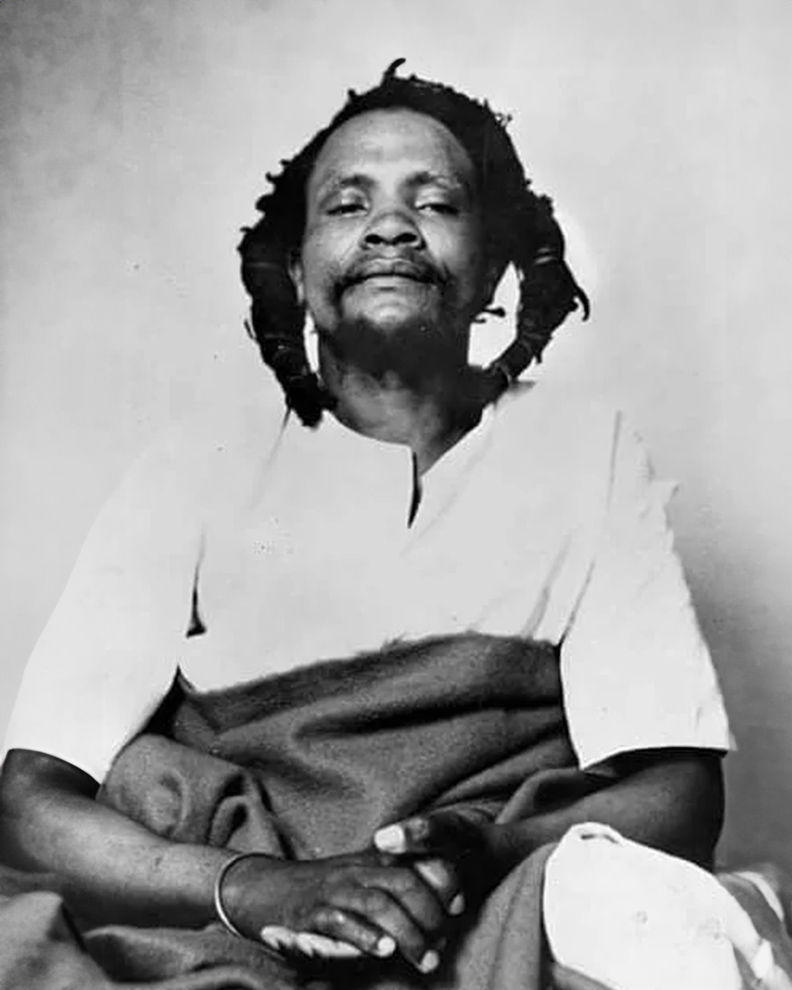

Kimathi’s captors took no chances. He was whisked to Nyeri hospital under heavy guard. British officials, mindful that Kimathi had once escaped jail years before, even placed a white soldier in his cell 24/7 to prevent any rescue or bribery attempt. Though wounded, Kimathi remained defiant. Father Marino, the local Catholic priest, visited the prisoner frequently. Kimathi, perhaps knowing his fate, spoke openly with the priest – about his childhood, his faith (he had been baptized Anglican), and his family – but steered conversation away from politics. To Marino, Kimathi expressed regret only that he hadn’t seen his young children in years due to the war. As the trial loomed, Kimathi also penned a moving letter to the priest, requesting that his son be educated well and that his detained wife Mukami be cared for by the church if possible. These human moments showed a softer side of the guerrilla general in his final days.\

Kimathi’s trial was a foregone conclusion. Instead of charging him with murders or rebellion (which might have invited probing questions about the legitimacy of colonial rule), the British chose the expedient path: they charged him simply with unlawful possession of a firearm and ammunition, under Emergency Regulations. It was a minor technical charge considering the scope of the war, but enough to carry the death penalty in the draconian emergency laws. The trial took place at a special court convened at Nyeri on 27 November 1956, with Chief Justice Kenneth O’Connor presiding and even a group of African jury-like “assessors” present (to give a veneer of fairness). Kimathi was wheeled into court on a stretcher, still recovering from the gunshot wound in his thigh. The evidence was straightforward – his captors had found him with a loaded revolver. Kimathi did not deny this. In his defense, he calmly stated that he carried the weapon to “defend myself in the forest” and that he had been “coming out to surrender in response to the government leaflets”, when the police shot him. The judge flatly rejected the surrender claim, noting Kimathi tried to flee when first spotted. After a brief deliberation, the court found him guilty of possession of a firearm and sentenced him to death by hanging. The entire trial and sentencing lasted barely a month – “laborious and intricate” only in a formal sense, but essentially a swift colonial drumhead trial to eliminate the insurgency’s figurehead.

Kimathi met his fate with legendary courage. He languished in Kamiti Maximum Security Prison in Nairobi for the next few months as appeals were filed and predictably dismissed. On the eve of execution, he was finally allowed to see his wife, Mukami Kimathi, who had been captured and detained in Kamiti as well. The colonial authorities, perhaps fearing outcry, permitted a final brief reunion on February 17, 1957. Guards reported that the two spoke softly for a long time. Kimathi told his wife not to grieve, for “I have committed no crime. My only crime is that I am a Kenyan revolutionary who led a liberation army.” He assured her he had “nothing to regret” and famously declared: “My blood will water the tree of Independence.” These words, spoken on the morning of his execution, have since become part of Kenya’s historical lore – a martyr’s testament that indeed foreshadowed Kenya’s independence a few years later. On February 18, 1957, in the gray pre-dawn hours, Dedan Kimathi was hanged at Kamiti Prison, just 36 years old. His body was buried in an unmarked grave within the prison grounds, along with dozens of other Mau Mau fighters who met the same fate. To this day the precise spot is uncertain (prison records were scant), and the Kenyan public was never given his body to conduct rites.

Kimathi’s execution sent shockwaves. The British colonial government believed removing Kimathi would deal a deathblow to Mau Mau – and militarily, it did. With him gone, the remaining fighters in the forests scattered; by early 1958 the Emergency was effectively over. Yet the image of Kimathi’s hanging had the opposite effect on the Kenyan populace’s psyche: he became a martyr. As one commentator noted, Kimathi’s trial and execution made him “a symbol of Britain’s brutal determination to maintain order…and a martyr of the Mau Mau movement”. Indeed, 1,090 Africans were hanged during the 1950s Emergency under British orders (some for simply helping the fighters with food), and Kimathi was now the most famous of these victims. Stories of his heroism and last defiant words spread secretly among Kenyans, keeping his legend alive even as colonial rule limped on for a few more years.

Aftermath and Memory Suppression

Kenya achieved independence in 1963, just six years after Kimathi’s execution, but the new nation’s leaders were ambivalent (even hostile) about Mau Mau’s legacy. Jomo Kenyatta – independent Kenya’s first president – had himself been jailed by the British (wrongly accused of leading Mau Mau), yet upon assuming power he pointedly downplayed the Mau Mau. Kenyatta’s government propagated a policy of national reconciliation that swept divisive wartime memories under the rug. “We shall not allow hooligans to rule Kenya,” Kenyatta brusquely replied in 1963 when asked about Mau Mau’s role in the new Kenya. He frequently spoke of the need to “forgive and forget” the past, to “bury the past” – effectively suppressing public discussion of the guerrilla war. Former Mau Mau fighters, whom many settlers and loyalists still regarded with fear or hatred, were not officially rehabilitated or compensated. In fact, the Mau Mau movement remained banned by law, as it had been under the colonial Emergency, for the next 40 years.

During Kenyatta’s 15-year rule (1963–1978), and even under his successor Daniel arap Moi (1978–2002), the public memory of Mau Mau was largely silenced. Independence Day (Uhuru Day, December 12) was celebrated every year with pomp, but it was never allowed to become a tribute to the Mau Mau struggle. There were no monuments for the forest fighters, no official honors – the national narrative favored the Kenyatta-led political struggle and diplomatic negotiations that had also contributed to independence. The violent and messy history of the Emergency was deemed inconvenient and was omitted from school textbooks and national commemoration. As historian David Anderson observes, Kenyatta extended no “rights, rewards or genuine compensation” to ex-Mau Mau, effectively marginalizing those who had fought in the forests. Many former fighters returned to their villages, only to find themselves landless (the land they bled for often still in settler or government hands) and stigmatized as “radicals.” Some faced harassment from local authorities if they tried to organize. The result was a collective amnesia enforced from above.

Mau Mau veterans coped by keeping their memories within their own ranks. In the Kenyan highlands, they formed informal groups to support each other and quietly remember fallen comrades. Every year on February 18 – the anniversary of Kimathi’s hanging – small groups of surviving Mau Mau would gather, far from the limelight, to honor their field marshal and the sacrifices of the war. These gatherings were not state-sanctioned, but they kept the flame alive. “Kimathi’s memory became a highly charged political issue,” Anderson notes, because acknowledging him meant acknowledging a part of history the post-colonial elite preferred to ignore. The continued absence of Kimathi’s grave was an especially painful point. Colonial authorities had never revealed where exactly at Kamiti Prison he was buried (likely to prevent the grave from becoming a shrine). For decades, Mukami Kimathi – his widow – and the family searched in vain for information on his remains. The Kenyan government largely avoided the issue during Kenyatta and Moi’s time, perhaps fearing that bringing Kimathi’s body home for a hero’s burial could rekindle Mau Mau glorification and, by extension, critique of those early leaders’ own records.

However, the grassroots pressure to acknowledge Mau Mau never completely vanished. The 1980s saw a few dissident voices (including former Mau Mau like General China and academics) calling for recognition of the “true freedom fighters.” Yet it was risky – Moi’s regime in particular was authoritarian and intolerant of anything that might spark social unrest or question the founding myths of the republic. Suppression of memory continued: as late as 1990, when Nelson Mandela visited Kenya shortly after his release from prison, he embarrassed the government by pointedly asking to see Dedan Kimathi’s grave and meet his widow. Moi’s officials had to admit they could not locate the grave and had largely ignored Kimathi’s family – a moment that underscored how neglected Mau Mau’s legacy had been. Mandela’s request, broadcast publicly, highlighted the irony that the outside world recognized Kimathi as a heroic freedom fighter, while his own country’s rulers kept him in the shadows.

Revival of His Legacy and Contemporary Commemoration

A significant shift in Kenya’s stance came with the political changes of the early 2000s. In 2002, a new reformist government under President Mwai Kibaki came to power, ending decades of KANU one-party rule. Kibaki’s administration moved quickly to rehabilitate the Mau Mau in official memory. In 2003, the Kenyan government formally lifted the ban on the Mau Mau movement – finally nullifying the colonial-era legislation that had outlawed Mau Mau and labeled its members terrorists. At the ceremony handing the Mau Mau veterans their new certificate of registration, Vice President Moody Awori acknowledged that it was “40 years late” and paid tribute to their sacrifices. This was a watershed: the surviving Mau Mau fighters could now register an association, speak openly of their struggle, and claim their place as freedom heroes.

The most visible honor came in 2007. On the 50th anniversary of Kimathi’s execution, President Kibaki unveiled a monumental bronze statue of Dedan Kimathi in central Nairobi. For the first time, Kenya publicly memorialized Kimathi in the heart of its capital. The 2.1-meter statue depicts him in combat fatigues with dreadlocks, holding a rifle and dagger – the image of a determined guerrilla. It stands on Kimathi Street, a road also named after him. The unveiling ceremony on 18 February 2007 was filled with emotional symbolism: aging Mau Mau veterans, including one of the few female field marshals, Muthoni Kirima, attended with tears in their eyes. “My heart has been heavy…wondering, have we been forgotten?” Kirima said, overcome that at last their struggle was honored. President Kibaki, in his speech, praised Kimathi as “a great man who not only sacrificed his life for Kenya’s liberation but also inspired others to fight against oppression.” This official commendation was a stark reversal from the “hooligans” label of decades past. The statue’s erection was celebrated by Kenyans across the country as long overdue recognition of the Mau Mau fighters.

Recognition of Kimathi’s legacy has continued to grow. Kenya’s 2010 Constitution even included provisions for honoring national heroes, reflecting the new consensus that figures like Kimathi are foundational to the nation’s history. Streets, schools and institutions have been (re)named after him, such as the Dedan Kimathi University of Technology in his home county of Nyeri. In 2015, as part of reconciliation efforts, the British government funded a memorial in Nairobi’s Uhuru Park to victims of colonial-era torture, explicitly including Mau Mau – an outcome of a landmark 2013 legal settlement in which over 5,000 Kenyan elders (Mau Mau veterans and others) received compensation from the UK for atrocities in the 1950s. This was a profound moment: the former colonial power formally acknowledged the suffering inflicted during the Emergency. The Uhuru Park memorial, unveiled by the British High Commissioner with Kenyan officials present, features a statue of a Mau Mau fighter and a member of the Kenya Army shaking hands – a symbol of reconciliation and closure.

On the matter of Kimathi’s remains, efforts have been made to locate and honor them. In 2003, the Kenyan government under Kibaki formed a committee to try to identify Kimathi’s burial site at Kamiti Prison. Despite exhuming many remains, a positive identification proved elusive (the burials were unmarked and comingled). In 2019, the Dedan Kimathi Foundation announced it had identified a likely gravesite at Kamiti. This raised hopes, but as of the mid-2020s, no confirmed exhumation has occurred and the Kenyan Interior Ministry has cast doubt on the claim. The Kimathi family and Mau Mau veteran groups continue to lobby for recovering his remains to give him a proper reburial. In May 2023, Mukami Kimathi – Kimathi’s widow who had tirelessly championed his memory – passed away in her 90s. Her funeral became a national event, with leaders pledging to continue the search for Field Marshal Kimathi’s grave so that husband and wife might one day rest together.

Today, Dedan Kimathi is widely taught in schools as a patriot, and his story is part of Kenya’s national narrative. Each year on the anniversary of his execution, commemorative events take place – often in Nyeri or Nairobi – celebrating Kimathi Day. In these events, speakers remind the youth of the ideals Kimathi fought for: land rights, freedom from oppression, and African unity. Notably, Kimathi’s influence has transcended Kenya’s borders. Nelson Mandela lauded him as an inspiration for South Africa’s anti-apartheid guerrillas. Freedom fighters in Zimbabwe and elsewhere have similarly paid homage to Mau Mau’s example. The image of Dedan Kimathi – dreadlocks, steadfast gaze, and steadfast resolve – has become a pan-African emblem of resistance to colonialism.

Historical and Political Significance in Kenya’s National Story

Dedan Kimathi’s life and legacy hold profound significance in Kenya’s national story. Historically, he stands as the foremost hero of the armed struggle for independence – the man who dared to lead peasants and workers into a fight against one of the mightiest empires of the time. The Mau Mau Uprising that he spearheaded between 1952 and 1956 was a pivotal chapter in ending British colonial rule in Kenya. While independence was achieved through a combination of factors (political negotiation, international pressure, etc.), the Mau Mau war made clear to the British that continued occupation would be met with fierce resistance. As Field Marshal, Kimathi personified that message. His execution in 1957 turned him into a martyr whose “blood watered the tree of independence,” as he foresaw. Indeed, many historians argue that Kenya’s independence in 1963 was, in no small measure, a fruit of the sacrifices of Kimathi and his fighters. The brutality of the British response – concentration camps, hangings, mass detentions – showed the world the ugly face of colonialism and galvanized anti-colonial solidarity. In this sense, Kimathi’s struggle had ripple effects beyond Kenya, energizing liberation movements across Africa.

Politically, Kimathi’s story also highlights the tensions in post-colonial nation-building. The early independent government chose a path of reconciliation and elite continuity, sidelining the more radical Mau Mau element. This had consequences: it left unresolved the very issues that Mau Mau had fought over, most notably the land question. Many Mau Mau veterans remained landless or in poverty, even as former loyalists and new elites acquired farms. The marginalization of Mau Mau also meant a segment of Kenyan identity was suppressed, which some say contributed to regional and class grievances in later decades (for example, discontent in Mau-Mau strongholds over unequal development). The eventual rehabilitation of Kimathi and Mau Mau in national memory (from 2003 onwards) can be seen as Kenya coming to terms with its own foundational violence and resistance, integrating it into a more honest narrative of the nation’s birth. This rehabilitation has helped heal rifts – for instance, the descendants of loyalists and Mau Mau now share a more unified view that both moderate leaders and fighters like Kimathi had roles in independence, reducing the old stigma around Mau Mau.

In Kenya’s popular culture and collective imagination, Dedan Kimathi has assumed the mantle of an iconic freedom fighter, akin to what Che Guevara is in Latin America or Bhagat Singh in India. His name adorns streets, his statues stand tall, and his life has been immortalized in literature and art – from the play “The Trial of Dedan Kimathi” by Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o and Micere Mugo (which portrays him as a symbol of resistance), to numerous songs and poems. Through these depictions, generations born long after 1957 have come to know Kimathi’s story as a source of national pride and a reminder of the cost of freedom. His famous quote, “I’d rather die on my feet than live on my knees,” is cited to instill patriotism and courage.

Moreover, Kimathi’s legacy continues to inform contemporary politics, especially around issues of historical justice. The Mau Mau veterans’ successful lawsuit against the British in 2013 (resulting in compensation and a memorial) was a direct outcome of the enduring respect for what Kimathi’s generation endured. It set a precedent for addressing colonial-era injustices. Domestically, Kenya’s leadership now actively honors Mau Mau veterans during national holidays, signalling that those once deemed terrorists are now celebrated as freedom fighters – a substantial reframing of the national story. This shift also serves as a unifying factor, as all communities can claim part of the Mau Mau heritage (for instance, Mau Mau had fighters or supporters from Kikuyu, Embu, Meru, Kamba, Luo and other groups, not only the Kikuyu as colonial narratives insisted).

Finally, in the grand arc of Kenya’s history, Dedan Kimathi represents the spirit of resistance – an unyielding refusal to accept injustice. His story is invoked whenever Kenya faces threats to its freedoms or social injustices in the post-independence era. For example, social justice activists in Mathare today reference Kimathi when demanding land rights or protesting against foreign military bases, arguing that the struggle against oppression continues in new forms. Thus, Kimathi’s significance is not confined to the past; he remains a touchstone for Kenyan values of courage, sacrifice, and the pursuit of true independence (including economic and social independence). As scholar Shiraz Durrani put it, Kenya’s war of independence did not end in 1963 – it transitioned into new battles against neo-colonialism and inequality. In that ongoing story, the memory of Field Marshal Dedan Kimathi serves as a guiding light, reminding the nation that the price of liberty is eternal vigilance, and that the heroes who first won freedom deserve honor and remembrance.

Sources:

- Barnett, D. & Njama, K. Mau Mau From Within: Autobiography and Analysis of Kenya’s Peasant Revolt. Monthly Review Press, 1966. (Eyewitness accounts of the Mau Mau war by participants, providing intricate details of guerrilla life and Kimathi’s role.)

- MacArthur, J. (ed.). Dedan Kimathi on Trial: Colonial Justice and Popular Memory in Kenya’s Mau Mau Rebellion. Ohio University Press, 2017. (Collection of trial records and essays on how Kimathi’s trial was conducted and later remembered.)

- Durrani, S. Kenya’s War of Independence: Mau Mau and its Legacy of Resistance to Colonialism and Imperialism, 1948-1990. Vita Books, 2018. (A comprehensive history arguing Mau Mau was a genuine war of independence; includes analysis of Kimathi’s leadership as “Mau Mau’s first Prime Minister”.)

- Anderson, D. Histories of the Hanged: The Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire. W.W. Norton, 2005. (Exposes the brutality of colonial counter-insurgency; notes 1,090 Africans were hanged and discusses how Kenyatta’s post-1963 government tried to “bury the past” of Mau Mau.)

- Maloba, W. Mau Mau and Kenya: An Analysis of a Peasant Revolt. Indiana University Press, 1993. (Analyzes Mau Mau’s origins, aims, and support base; characterizes it as a nationalist peasant revolt, countering earlier colonial narratives