Before missionaries arrived with Christianity and traders brought Islam inland, the people of Kenya already lived within rich, coherent systems of faith. Their religions were not codified in scriptures but woven into everyday life—embedded in land, family, birth, death, and the rhythm of the seasons. Each community, from the Kikuyu and Kamba of the highlands to the Luo of Nyanza and the Mijikenda of the coast, held distinctive ways of relating to the divine. Yet these diverse traditions shared a common thread: the belief that the world was ordered by a supreme creator, sustained by ancestors, and balanced through human duty and moral harmony.

According to Mbiti (1975), African religion in its local forms was “lived rather than professed,” a way of being that bound people to their environment and to one another. In Kenya, spirituality permeated governance, law, and kinship—it determined how a wrong was punished, when crops were planted, and which oaths could not be broken. Magesa (1997) describes this as a “moral universe of abundance,” where everything existed in a sacred relationship rather than in opposition between the spiritual and the physical.

Precolonial Kenya thus cannot be understood without its spiritual foundations. Mountains, forests, lakes, and ancestral shrines served as centers of communion with God. Prophets, healers, and seers mediated between the visible and invisible worlds, ensuring balance in times of illness or conflict. When the colonial state later dismissed these systems as “superstition,” it not only displaced belief but dismantled the moral and political fabric that had ordered society for generations.

This article explores how religion and spiritualism functioned in Kenya before colonial rule—how the people understood God, the ancestors, and the moral order that connected them. It also traces how these traditions adapted under external pressures, leaving traces that still shape Kenya’s religious landscape today.

The Idea of God Across Communities

Across Kenya’s diverse societies, belief in a supreme creator was universal long before the arrival of organized religions. Each community used its own name and attributes for this being, reflecting its environment and way of life. What varied was not the existence of God but the relationship between the divine, the land, and the people.

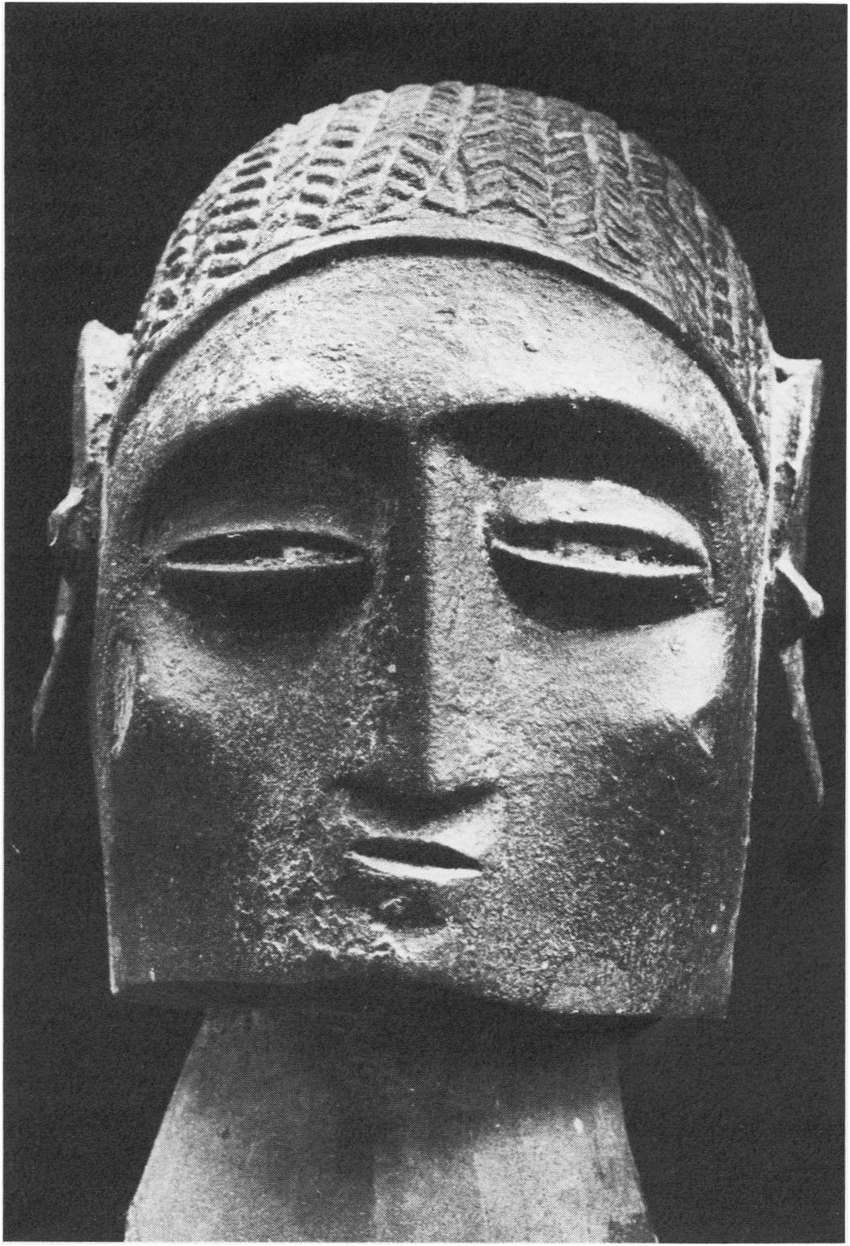

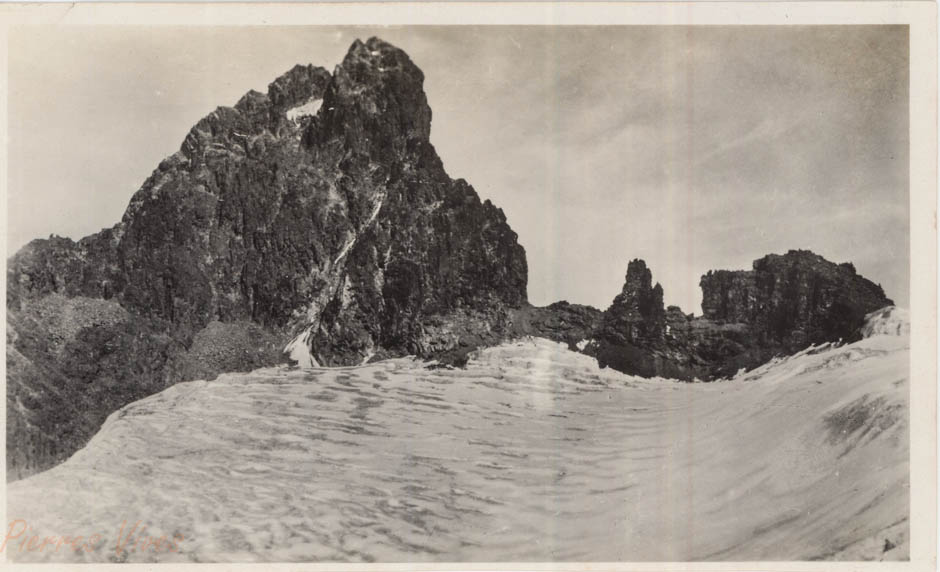

Among the Kikuyu, God was known as Ngai, the giver of life who resided atop Mount Kenya (Kirinyaga). Ngai was both transcendent and near, manifesting in rain, thunder, and the fertility of the soil. As Kenyatta (1938) observed in Facing Mount Kenya, the Kikuyu “lifted their eyes to the snow peak of Kirinyaga, for there they believed Ngai lived when he visited the earth.” Sacrifices of goats and prayers offered under sacred fig trees (mugumo) symbolized the community’s covenant with the creator.

For the Maasai, the supreme being was Enkai (also spelled Engai), the god of rain and fertility. Enkai embodied both benevolence and wrath, mirrored in the cycles of drought and abundance that defined pastoral life. The Maasai related to Enkai through the laibon, a prophet and spiritual leader who interpreted divine will in matters of war, weather, and health.

The Luo of western Kenya worshiped Were (also known as Nyasaye), a god of justice who rewarded moral conduct and punished wrongdoing. Were was invoked during oath-taking, harvests, and illness, often through animal sacrifices near sacred groves or lakeshores. Similarly, the Kalenjin people believed in Tororot, a sky god associated with the sun, thunder, and cosmic order. For them, Tororot governed both natural forces and moral law, and rituals of purification or thanksgiving reaffirmed communal balance.

Along the coast, the Mijikenda revered Mulungu, a creator god who withdrew from human affairs but remained accessible through ancestral spirits. Their nine fortified settlements, known as kaya forests, served as both political and sacred centers. Entry into a kaya was restricted to elders who performed rituals to protect the community from calamity.

Despite regional variations, these traditions shared several philosophical constants. As Mbiti (1975) noted, “God is not withdrawn from the world; He is present in nature and in man.” This sense of divine immanence made spirituality inseparable from ecology—rain, harvest, and livestock were all sacred gifts, and environmental stewardship was a religious duty. Hallen (2002) interprets this as a form of indigenous rationality: the idea that moral and cosmic order were parts of the same system, sustained through right living.

The precolonial Kenyan understanding of God was thus not abstract theology but a lived cosmology. The divine was approached through gratitude, ritual, and ethical responsibility rather than creed or scripture. This worldview made religion a foundation of both morality and governance, a framework that colonial rule would later attempt to redefine.

Ancestors and the Living Dead

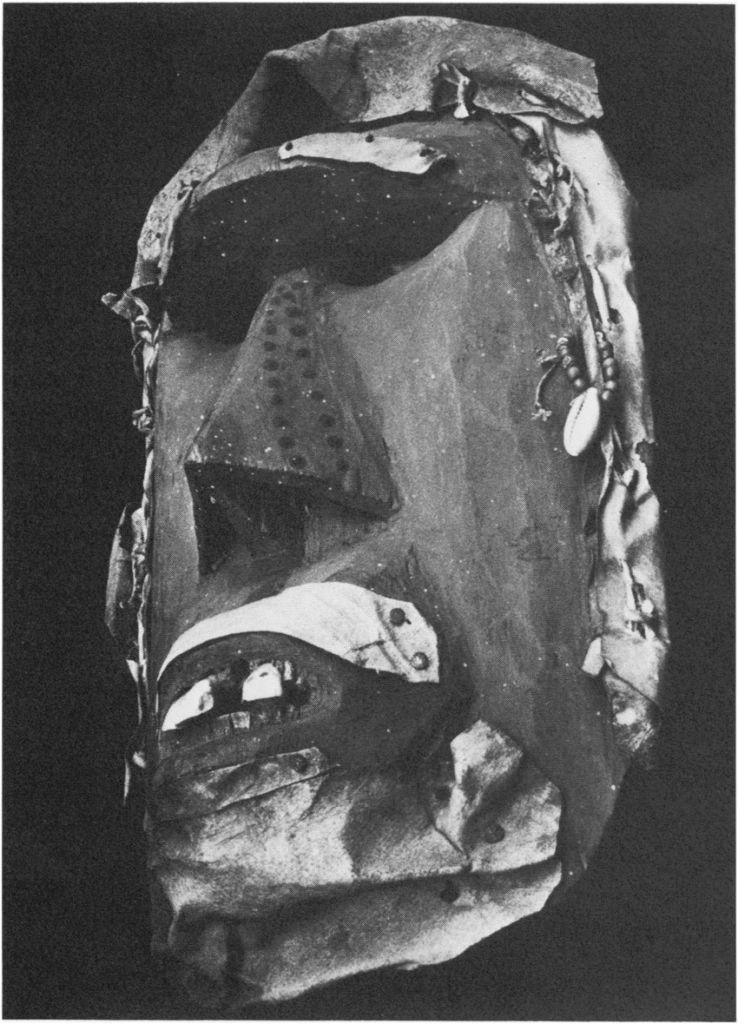

In precolonial Kenya, religion was not limited to the worship of a distant deity. The people understood life as a continuum linking the living, the dead, and those yet to be born. Ancestors—often referred to as the “living dead”—formed the bridge between human beings and God. Their spirits were not regarded as ghosts but as active members of the community whose approval or displeasure shaped everyday life.

Mbiti (1975) explains that in African thought, death did not end existence but changed its form. The departed joined the realm of the ancestors, where they watched over the living and communicated with them through dreams, illness, or blessings. This belief was shared across many Kenyan communities, though expressed differently in each. Among the Kikuyu, ancestors were honored through offerings of food, milk, or beer poured onto the ground during family rituals. The elders often called upon the spirits of lineage founders, asking them to bless the harvest or to reconcile quarrels. Such ceremonies were less acts of worship than of kinship—they reaffirmed unity between the living family and its eternal guardians.

The Luo similarly believed that death did not sever ties with the family. The spirits of the departed, known as juogi, could bring either protection or misfortune. If neglected, they might cause sickness or infertility as a reminder of forgotten obligations. To appease them, families performed tero buru—funeral ceremonies involving song, dance, and the sacrifice of animals—to celebrate the passage of the deceased into the spirit world. The living continued to invoke their ancestors’ names in prayers for health, children, or rain.

Among the Kamba and Embu, the spirits of the dead were intermediaries between God (Mulungu or Ngai) and humanity. Before major undertakings—such as planting, warfare, or initiation—elders offered libations to seek ancestral approval. These rituals reinforced social morality, for to offend an ancestor was to risk communal misfortune.

The Luhya communities held a similar reverence. Ancestors were remembered through annual feasts and prayers to ensure peace and prosperity. Failure to honor them could lead to misfortune, seen not as random tragedy but as moral imbalance. The living maintained the relationship through offerings and by upholding family ethics, since the ancestors were thought to reward honesty and discipline while punishing deceit.

This belief system produced a profound sense of accountability. As Magesa (1997) writes, the ancestors “keep alive the moral order of the community” because they represent the highest authority of custom. They were not feared as tyrants but respected as custodians of justice. Even oaths sworn before elders invoked ancestral witnesses, binding the swearer not only to social norms but to spiritual consequences.

The concept of the “living dead” also shaped how time and memory functioned in Kenyan spirituality. Life extended backward into lineage and forward into legacy. Hallen (2002) observes that such a view dissolves the Western boundary between sacred and secular: moral actions carried spiritual weight because each deed resonated through both worlds. In this way, religion, memory, and morality were inseparable in precolonial Kenya.

The ancestors’ enduring presence gave meaning to suffering and purpose to duty. Every prayer, sacrifice, or act of reconciliation reaffirmed this sacred connection. To live rightly was to live in harmony with both the visible and invisible community—a worldview that colonial ideologies of individualism would later struggle to comprehend.

Mediators of Power: Prophets, Healers, and Seers

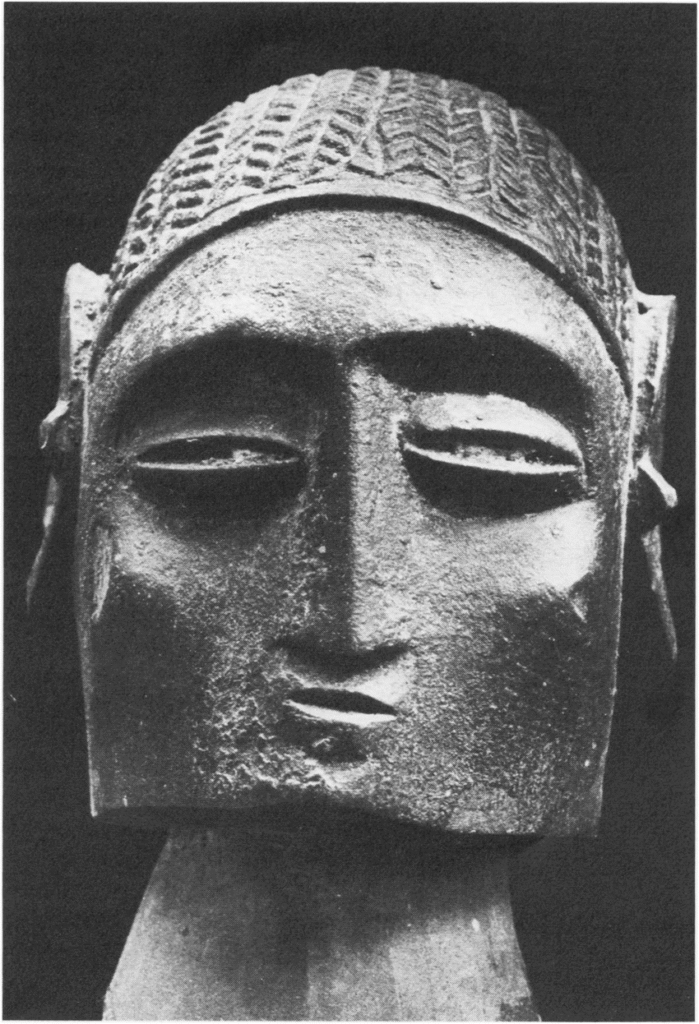

The spiritual world of precolonial Kenya was not distant or abstract. It was dynamic, interactive, and mediated through chosen individuals who could interpret divine will. Prophets, healers, and seers served as the human channels through which communities understood misfortune, sought healing, and restored moral balance. These figures were not separate from society—they were its conscience, custodians of justice and wisdom.

Across Kenya’s regions, each community had specific spiritual specialists. Among the Maasai, the laibon was both prophet and ritual leader. The laibon advised warriors before raids, blessed livestock, and interceded with Enkai for rain. Renowned figures like Mbatian and later his son Lenana were central to Maasai unity; their prophetic authority could end wars or legitimize leadership. Their power was not political in the Western sense but spiritual—the ability to align human action with divine order.

The Kikuyu recognized mundu mugo, diviners and herbalists who combined practical medicine with spiritual insight. They diagnosed illness as both a physical and moral condition, interpreting dreams, omens, and ancestral displeasure. Some, like the famed prophet Mugo wa Kibiru, were revered as visionaries who foretold the coming of white strangers and the upheavals that followed. Kenyatta (1938) described such individuals as “those to whom the spirits whisper,” revealing the sacred continuity between revelation and responsibility.

Among the Luo, spiritual power manifested through ajuoga (diviners) and jothur, exorcists who mediated between humans and juogi—the spirits of the dead. The ajuoga used symbolic objects such as gourds, cowrie shells, and bones to read divine signs. Illness or misfortune was rarely viewed as random; it was interpreted as a message from the spiritual realm. Healing involved restoring harmony between the afflicted person and the unseen forces surrounding them.

The Kamba and Embu also had their ritual experts, known for their mastery of herbs, charms, and incantations. These healers were essential in managing both personal ailments and communal crises. When drought struck, they led rainmaking ceremonies, sacrificing goats or bulls under sacred trees to appeal to Mulungu or Ngai. Their practices combined observation of the natural world with deep spiritual intuition—what Hallen (2002) calls “indigenous rationality,” a philosophy where knowledge of nature and metaphysics coexisted.

In western Kenya, the Luhya and Teso communities had diviners and prophets who guided social and political decisions. Among the Bukusu, for instance, seers could declare taboos (emikoye) or cleansing rituals (misambwa) after bloodshed or calamity. Such pronouncements carried legal weight, since defying spiritual law invited communal punishment from both humans and ancestors.

These mediators of power embodied what Magesa (1997) describes as the “moral transaction” between the living and the divine. Their authority derived from service rather than status; they were bound by ethical codes that prohibited greed and false prophecy. When colonial officers later labeled them “witchdoctors,” they misinterpreted a system built on accountability and moral reciprocity. For precolonial Kenyans, spiritual knowledge was not secret magic but public responsibility—its purpose was to heal, guide, and preserve harmony.

The prominence of these figures also shows that precolonial religion was not rigidly hierarchical. Divine insight could emerge through dreams, visions, or inspiration, transcending social rank or gender. Women, too, served as mediums and healers, particularly among the Luo, Kamba, and Mijikenda. Their participation affirmed that spiritual authority flowed from experience and character, not office or wealth.

Through prophets, healers, and seers, Kenyan societies maintained a balance between destiny and duty. These mediators were living testaments to the principle that power, in its truest form, was sacred—meant to sustain life, not dominate it.

Religion as Moral Order

In precolonial Kenya, religion was not a separate sphere of life—it was the foundation of law, ethics, and social cohesion. Every act, from birth to burial, was governed by moral principles rooted in spiritual belief. To live rightly was to live in harmony with both the human community and the unseen world. The moral and the sacred were one and the same.

Mbiti (1975) wrote that in traditional African life, “there is no formal distinction between the religious and the non-religious, between the sacred and the secular.” This was clearly true in Kenya, where social norms and divine will were seen as inseparable. Wrongdoing was not merely an offense against another person; it was a disturbance of the cosmic order that required ritual purification. Moral behavior ensured that the community remained in good standing with the ancestors and the creator.

Among the Kikuyu, justice was both social and spiritual. Serious crimes—murder, theft, adultery, or false oaths—were believed to attract thahu (ritual impurity) that could spread misfortune throughout the community. Cleansing ceremonies, involving elders, sacrifices, and confessions, restored balance. Kenyatta (1938) described how moral education began in childhood, through initiation rites that taught young people their obligations to family, neighbors, and Ngai. Law, therefore, was not enforced through fear of punishment but through fear of cosmic imbalance.

The Luo held similar beliefs, grounded in communal ethics. Moral obligations such as hospitality, honesty, and respect for elders were spiritual duties. Violations, especially of sexual or familial taboos, were seen as dangerous acts that could invite illness or drought. Cleansing rituals (chodo gi juogi) were used to reestablish peace between the living and the ancestors.

For the Kamba, ethics were expressed through the concept of mwea, or balance. Social harmony depended on fulfilling one’s role in family and clan. Breaking taboos—lying under oath, mistreating guests, or disrespecting elders—was believed to provoke Mulungu’s disfavor. Similarly, among the Maasai, enkanyit (respect and moral uprightness) was a cardinal virtue. To act with enkanyit meant to honor one’s obligations to kin, cattle, and Enkai. Violation of this moral order could bring drought or sickness upon the whole community.

Across Kenya, oaths and curses served as instruments of justice. They were public rituals that bound individuals to truth and accountability. Oaths were taken before elders or sacred objects, invoking ancestors as witnesses. To swear falsely was not only a social crime but a spiritual one—the perjurer risked death or disgrace. The Bukusu, for instance, practiced oath-taking under the kamakhya tree, where breaking the vow was believed to summon ancestral punishment.

Magesa (1997) interprets such systems as expressions of “the moral traditions of abundant life,” where the goal of religion was not salvation in an afterlife but the flourishing of the community in this world. Morality was measured by how well one upheld life—through fertility, peace, generosity, and justice. A person’s reputation was not defined by wealth but by utu, the quality of being fully human through right conduct.

The role of elders in enforcing this moral order was also deeply religious. Councils of elders did not act as secular courts but as spiritual guardians. Their judgments invoked the authority of the ancestors and divine law. Among the Kikuyu, Embu, and Meru, an oath of reconciliation—kiriro—was sealed with shared meals and libations, symbolizing restored unity. Among the Luhya and Luo, disputes were settled through communal mediation rather than exile or imprisonment.

This spiritual understanding of justice produced social stability. As Hallen (2002) notes, indigenous African ethics were not based on written codes but on consensus and collective memory, guided by the conviction that moral order sustains life itself. In precolonial Kenya, religion was thus both constitution and conscience—a living system of law that bound the seen and unseen worlds together.

Colonial Disruption and Reinterpretation

The arrival of colonial rule in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries profoundly altered Kenya’s spiritual landscape. Missionaries, administrators, and settlers redefined local religion through the lens of European Christianity, labeling traditional beliefs as superstition or witchcraft. What had been the foundation of law and morality was now treated as an obstacle to civilization.

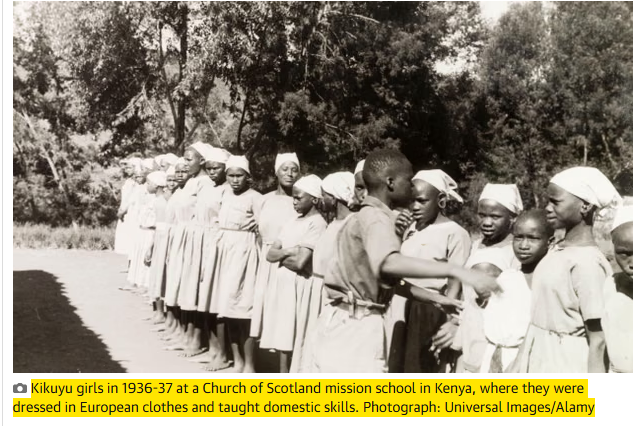

Missionaries were often the first agents of this transformation. They built schools and churches that promised literacy and salvation but also demanded the rejection of indigenous rituals. The Church of Scotland Mission and the Church Missionary Society, active in Kikuyu areas, taught that the worship of Ngai and veneration of ancestors were idolatrous. Converts were required to abandon initiation rites, polygamy, and traditional healing practices. For many communities, conversion offered material opportunities—education, medicine, and trade—but at the cost of cultural dislocation.

Colonial authorities reinforced this process through legislation. The Witchcraft Ordinance of 1925 criminalized many indigenous practices under the vague category of “sorcery.” Diviners, rainmakers, and prophets—once respected as moral leaders—were now surveilled, arrested, or silenced. As Anderson (2005) and Berman (1990) note, this legal suppression was also political: by undermining spiritual leaders, the colonial state weakened centers of indigenous authority that might challenge its control.

The female circumcision controversy of 1929–1930 illustrated how religion became a battleground for cultural autonomy. When Protestant missions banned the practice among Kikuyu Christians, the community viewed it not as a moral issue but as an attack on their social and religious identity. The crisis led to the formation of the African Independent Pentecostal Church of Africa (AIPCA) and other independent schools and churches, where worship was fused with nationalism. These movements symbolized an early attempt to reclaim spiritual sovereignty within a colonial framework.

Islam, too, was reshaped by colonial encounters. Although established along the coast long before British rule, Islamic institutions came under new regulation. The colonial government promoted certain Muslim leaders while restricting others, using religion to maintain order. This selective patronage diluted Islam’s autonomy and integrated it into the bureaucratic machinery of the Protectorate.

At a broader level, colonial education separated religion from everyday life. The missionary curriculum replaced oral traditions and ecological ethics with Western rationalism and the notion of a distant, transcendent God. Sacred groves were cleared for plantations, shrines were desecrated, and mountains like Kirinyaga were reimagined as symbols of conquest rather than reverence. Magesa (1997) argues that this alienation “emptied the African world of its moral center,” replacing the relational ethics of abundance with an imported morality of guilt and salvation.

Yet, despite repression, traditional spirituality did not vanish—it adapted. Many converts practiced a dual faith, attending church on Sundays while consulting diviners or honoring ancestors in private. Independent churches incorporated drumming, prophecy, and healing into Christian worship, creating a hybrid religiosity that defied colonial classification. In rural areas, rituals of cleansing, rainmaking, and oath-taking continued discreetly, preserving a sense of moral continuity.

By the 1940s and 1950s, as nationalist movements gained momentum, religion again became a source of resistance. Leaders of the Kikuyu Central Association and later the Mau Mau movement drew moral legitimacy from indigenous oaths that bound fighters to secrecy and sacrifice. These oaths—rooted in the same cosmology that missionaries had condemned—transformed into political tools of liberation. Colonial officials, misunderstanding their spiritual gravity, saw them only as instruments of rebellion.

Thus, colonial disruption did not erase Kenya’s traditional religion; it forced it underground and changed its form. What survived was not mere ritual but a resilient worldview: the conviction that justice, truth, and community were sacred duties. As Mbiti (1975) observed, even under the pressures of modernity, “African peoples still look beyond themselves for spiritual support, for life remains a religious drama.”

Legacy and Continuity

Despite a century of missionary expansion, colonial suppression, and modern secularization, the spiritual foundations of precolonial Kenya continue to shape the country’s moral imagination. Traditional religion has not disappeared; it has adapted, merging with Christianity, Islam, and contemporary culture in complex ways. Beneath Kenya’s formal religious identities lies an enduring belief that life, land, and morality remain sacredly connected.

Ritual practices rooted in precolonial cosmology still persist. Among the Kikuyu, prayers to Ngai are still offered on Mount Kenya’s slopes, especially during national droughts or crises. Elders continue to meet under fig trees to perform cleansing ceremonies when social order is disrupted—whether by political violence or moral transgression. Among the Luo, family rituals for appeasing ancestral spirits (chodo gi juogi) remain integral to funerary traditions, blending Christian hymns with libations and sacrifices. The Mijikenda still revere the kaya forests as both ecological sanctuaries and sacred inheritance, protected by elders who serve as custodians of community ethics.

These practices reveal a continuity that Mbiti (1975) described as “the living thread of traditional religion”—a system that endures not through temples or texts but through habit, story, and ritual. The same moral principles that guided precolonial society—respect for elders, communal solidarity, and reverence for the earth—remain embedded in Kenyan life. They appear in political oaths, reconciliation ceremonies, and national commemorations that call upon ancestral blessings.

The persistence of these traditions also highlights Kenya’s broader synthesis of faiths. Many Kenyans today identify as Christian or Muslim while retaining elements of traditional spirituality. Magesa (1997) explains this as “the continuity of moral meaning,” where African values of reciprocity and balance survive within imported religions. Church leaders often incorporate blessings over soil or water, echoing the older cosmology of sacred ecology. In rural areas, diviners and healers continue to operate alongside modern clinics, demonstrating how spiritual and physical health remain intertwined.

At the national level, echoes of precolonial religion appear in Kenya’s cultural symbols. The motto “Harambee”—pulling together—reflects an older ethic of collective responsibility. Ceremonies of cleansing after electoral violence or natural disaster, led by elders and clergy alike, follow patterns that predate colonialism. Even in political discourse, appeals to ancestral unity and divine providence trace their roots to traditional notions of cosmic balance.

Yet, the survival of indigenous spirituality also raises questions about memory and erasure. Much of Kenya’s religious past was undocumented or deliberately distorted by colonial ethnography. As Hallen (2002) notes, reclaiming these traditions is not merely an act of nostalgia but of philosophical recovery—it restores African systems of reasoning and morality that colonialism sought to delegitimize.

In the twenty-first century, renewed interest in African spirituality among scholars, artists, and environmentalists reflects a desire to reconnect with these deeper moral frameworks. The reverence for sacred forests, rivers, and mountains aligns with modern environmental ethics, showing that traditional religion’s respect for nature was both spiritual and sustainable.

Ultimately, the story of religion in Kenya before colonialism is not one of disappearance but of endurance. The gods of the mountains, the whispers of the ancestors, and the moral laws of community have survived through adaptation. They continue to remind Kenyans that their identity is not only political or economic but profoundly spiritual—a living dialogue between the past and the present, the visible and the unseen.

References

Anderson, D. (2005). Histories of the hanged: Britain’s dirty war in Kenya and the end of empire. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Berman, B. (1990). Control and crisis in colonial Kenya: The dialectic of domination. London: James Currey.

Hallen, B. (2002). A short history of African philosophy. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

Kenyatta, J. (1938). Facing Mount Kenya: The tribal life of the Gikuyu. London: Secker and Warburg.

Magesa, L. (1997). African religion: The moral traditions of abundant life. Nairobi: Paulines Publications Africa.

Mbiti, J. S. (1975). Introduction to African religion. London: Heinemann.