In the decades after independence, Kenya found its voice not only in politics and literature but in song. The 1960s and 1970s saw a musical awakening that blended local traditions with the electric pulse of a modern nation. From Kikuyu guitarists singing of morality and land to Kamba drummers turning village rhythms into dance hits, Kenya’s regional sounds became the heartbeat of national identity.

This was not just entertainment — it was a cultural negotiation. The Kikuyu, Kamba, Luo, and Luhya musicians each brought their own languages, instruments, and performance philosophies. When these sounds met on Nairobi’s River Road and in state-funded choirs, a new kind of Kenyan music was born: rooted in vernacular pride yet shaped by the shared dream of unity.

Kikuyu Pop: From Rural Strings to Studio Legends

Among Kenya’s highland peoples, the Kikuyu produced one of the earliest and most influential popular music traditions. In the years following independence, singers like Joseph Kamaru, DK wa Maria, and Wanganangu turned simple guitar melodies into instruments of storytelling and protest. Their songs drew from the traditional mũthũngũri rhythm — a circular pattern played during harvest dances — but added modern instrumentation: electric guitars, bass lines, and percussion influenced by Congolese rumba and American country music.

Kamaru, often called the “king of Kikuyu music,” used song as a form of social commentary. In the 1970s, his lyrics addressed morality, urbanization, and corruption, often clashing with state censors. As music historian Njogu (2008) notes, Kikuyu pop became a “moral economy of sound,” where song served as both confession and critique. The genre’s popularity rested on its balance between the sacred and the secular — warning listeners about moral decay while celebrating love and resilience.

By the 1980s, the River Road recording scene in Nairobi had turned Kikuyu pop into a full-fledged industry. Studios like Melodica and Chandarana pressed thousands of 45rpm vinyl records. The music, sung in Gikuyu and Swahili, traveled across bus stations and rural markets, creating a vernacular media network long before FM radio. The Kikuyu guitar sound — melodic, conversational, and harmonically simple — became a defining element of Kenya’s sonic identity.

The Muungano Choir and the Sound of National Harmony

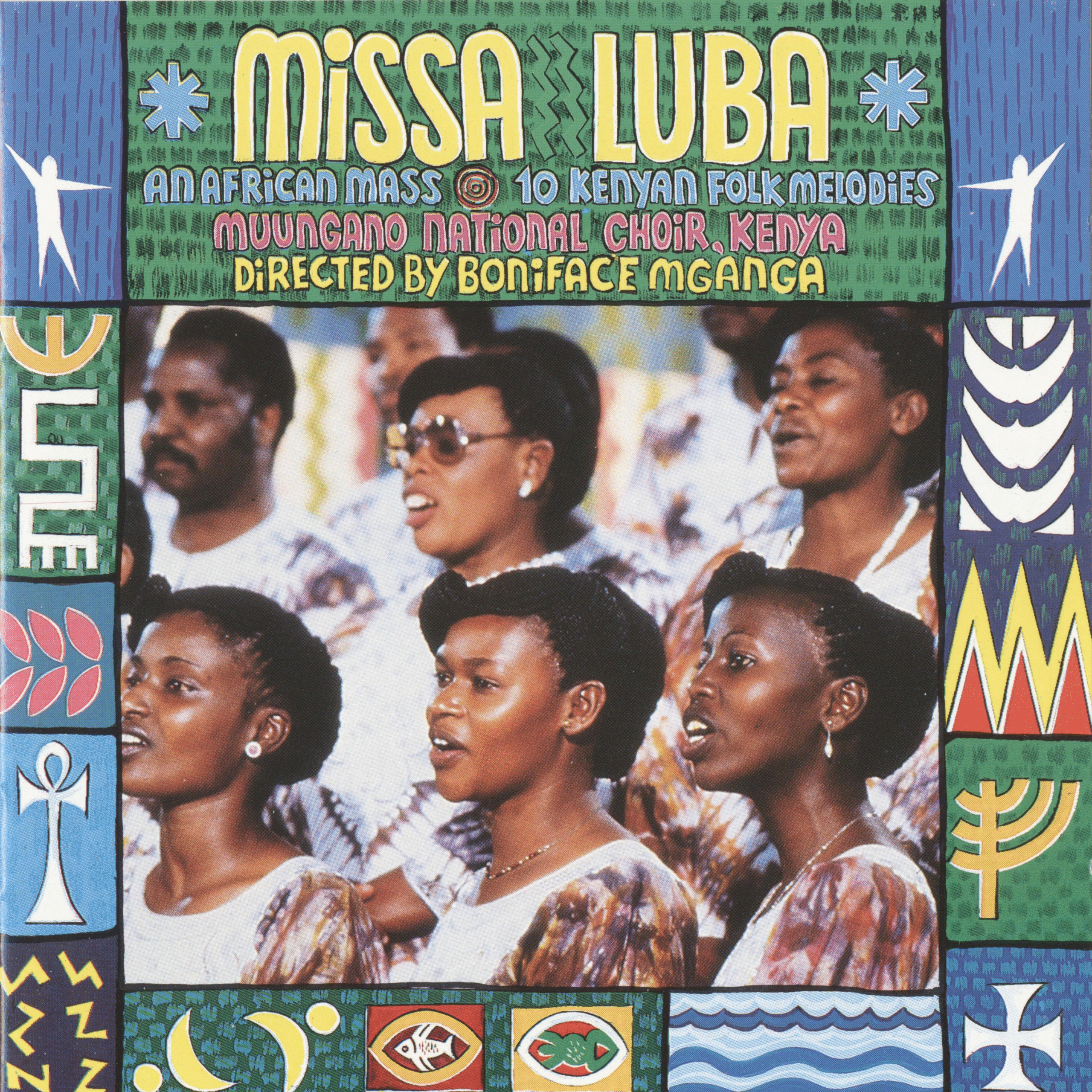

In the late 1970s, Kenya’s music entered a new phase — one driven by the state’s desire to project national unity. Boniface Mganga, a music educator and composer, founded the Muungano National Choir in 1979. Its name, Muungano, means “unity” in Swahili, reflecting the choir’s mission to blend Kenya’s diverse voices into one national sound.

Under President Daniel arap Moi’s government, Muungano became both a musical and political project. The choir performed at national holidays, presidential functions, and international tours, presenting Kenya as a harmonious nation of many languages. Their songs — such as “Safari ya Bamba,” “Amani na Upendo,” and “Tawala Kenya” — fused Christian choral structure with African call-and-response, polyrhythmic drumming, and ululation.

Mganga’s arrangements reflected Kenya’s regional diversity: Kikuyu choral harmonies, Kamba drumming, and Swahili lyrics. According to Mwenda Ntarangwi (2003), Muungano’s performances created “a sonic map of Kenya,” a musical embodiment of Harambee — collective effort. But this unity came with tension. As Kenya moved deeper into the one-party era, the state increasingly used music to promote loyalty to Moi. Songs of peace and progress blurred with propaganda.

Still, Muungano’s artistry outlived its politics. The choir’s recordings for Polydor and UNESCO earned international acclaim, inspiring a generation of Kenyan church choirs and school ensembles. Through them, the idea of a shared national sound — one that respected local languages while celebrating national belonging — took root.

Kamba Beats: From Drums to Dancefloors

While Kikuyu musicians dominated the record industry, the Kamba of eastern Kenya developed a distinct and rhythmically intense pop tradition that shaped the country’s dance music. Rooted in Kilumi drumming — a communal ceremony invoking ancestral spirits — Kamba music emphasized call-and-response, fast-paced percussion, and circular melodies that mirrored traditional dance.

The breakthrough came in the 1970s with Kakai Kilonzo and his band Kilimanjoro. Kilonzo’s hits such as “Mama Sofia” and “Kikamba Love” fused Kilumi rhythms with benga-style guitars, creating a hybrid genre that appealed to both rural and urban audiences. His lyrics, often romantic or reflective, gave Kamba pop a poetic identity distinct from the moral sermonizing of Kikuyu songs.

In the 1980s and 1990s, Ken wa Maria and the Yatta Band carried this tradition into modernity. Their music combined traditional beats with electric keyboards and high-tempo percussion, laying the foundation for what fans called “Kamba beats.” The sound was raw, vibrant, and unapologetically local — music that celebrated weddings, matatu culture, and rural pride.

At the same time, Kamba women musicians such as Esther Mbondo and Mwende Katumbi redefined the genre’s social role. Their performances at community events blurred the line between sacred and secular, much like Kikuyu and Luo performers before them. Through song, they addressed everyday struggles — poverty, marriage, migration — giving Kamba pop its enduring emotional depth.

Crossroads: Faith, Commerce, and Cultural Continuity

By the 1990s, Kenya’s music scene had fractured into two main forces: commercial pop and religious music. Yet, as Mbugua (2014) observes, these streams were not separate; they constantly borrowed from each other. The influence of the Muungano Choir was evident in the structure of modern gospel ensembles like Safari Voices Africa and Kayamba Africa, which combined a cappella harmonies with regional rhythms.

Meanwhile, Kikuyu and Kamba secular artists increasingly referenced religious imagery to appeal to moral audiences. Ken wa Maria’s “Fundamentalist” (2010) plays with biblical metaphor, while Kikuyu singers like Muigai wa Njoroge and Samidoh inject social commentary into songs about justice and politics. In both traditions, the sacred remains intertwined with the everyday.

The digital revolution further reshaped Kenya’s regional sound. YouTube, Facebook, and TikTok have globalized once-local music scenes. A Kikuyu song recorded in Nakuru can reach diaspora audiences in London within hours. Kamba artists use WhatsApp groups to promote new tracks, turning fans into distributors. The internet has made regional pop both more visible and more competitive, but it has also revived pride in singing in one’s mother tongue.

From Villages to Global Streams

The evolution from Kikuyu pop and Kamba beats to today’s digital scene reveals how regional music sustained Kenya’s cultural autonomy through changing political eras. During colonial rule, missionaries had condemned indigenous music as pagan. After independence, state propaganda often appropriated it for national unity. Yet, across both periods, local musicians maintained creative independence by using their languages and rhythms as tools of survival.

The Kikuyu guitar tradition continues through artists like Jose Gatutura and Samidoh, whose songs mix moral lessons with contemporary issues. Kamba pop, led by figures such as Alex Kasau Katombi, blends traditional percussion with Afrobeat influences, ensuring continuity while appealing to younger listeners.

What connects them all — from Muungano’s choral harmonies to Kamba dance rhythms — is a belief that music expresses truth in ways politics cannot. Each song carries a piece of Kenya’s history: the pain of colonial silencing, the optimism of independence, and the creativity of everyday survival.

Legacy: The Local in the National

The story of Kikuyu and Kamba pop is, in essence, the story of Kenya’s cultural federalism — unity through difference. Kikuyu musicians turned the guitar into a moral compass; Kamba artists turned rhythm into celebration. Together, they expanded Kenya’s musical identity beyond Swahili pop and coastal taarab, grounding it in vernacular pride.

The Muungano Choir symbolized the high point of state-driven unity, while Kamba beats represented grassroots creativity beyond Nairobi’s elite circuits. Their coexistence revealed a national paradox: Kenya’s most unifying sound was born from its most local traditions.

Today, as global Afrobeats dominates the airwaves, Kenya’s regional artists continue to remind listeners that local stories matter. Their music carries not just melody, but memory — a testament that every drumbeat and lyric, from the hills of Machakos to the slopes of Murang’a, contributes to the unfinished song of the nation.

References

Mbugua, N. (2014). Kenyan music in transition: The digital age and the politics of identity. Nairobi: East African Publishers.

Mwenda Ntarangwi, M. (2003). Gender, performance, and cultural politics: Kenyan music and identity. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Njogu, K. (2008). Cultural production and social change in Kenya. Nairobi: Twaweza Communications.