The Arrival on the Monsoon Winds

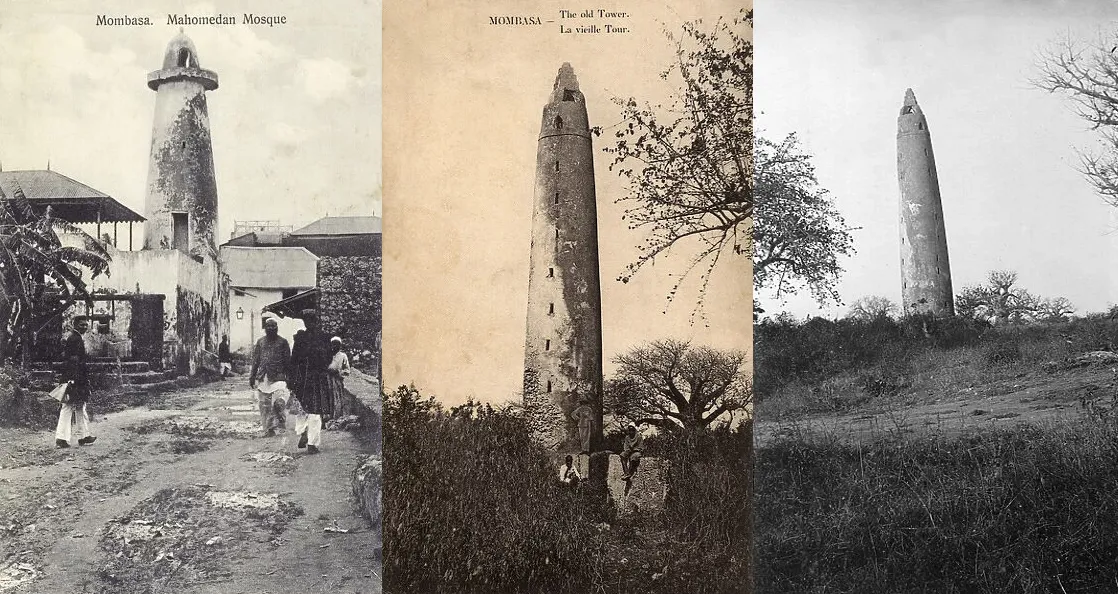

Long before Nairobi was a swamp or Mombasa a fort, the Indian Ocean carried dhows on seasonal monsoon winds to the East African coast. Alongside cloth, spices, and ceramics, the Arab and Persian sailors brought with them Islam. By the 9th century, Muslim communities dotted the coast — in Lamu, Mombasa, Pate, and Malindi. Mosques rose in coral stone, their mihrabs oriented toward Mecca, their minarets modest but visible reminders that faith had arrived with commerce.

For centuries, Islam in Kenya was coastal. It flourished in Swahili towns where Arab traders intermarried with Bantu-speaking Africans, producing the rich Swahili culture: a language mixing Arabic and African words, an architectural style blending Islamic and local motifs, and a society that identified proudly as Muslim and cosmopolitan. Inland peoples, however, remained largely untouched until the 19th century. Islam’s geography in Kenya thus mirrored its maritime roots — a religion born of the ocean, anchored to the coast.

Swahili Culture and the Mosque as Power

On the coast, Islam was never just private devotion. It was also political power. Swahili rulers — the sheikhs and sultans of Mombasa, Malindi, and Lamu — drew legitimacy from Islam, aligning themselves with the broader Muslim world. Alliances were struck with Yemen, Oman, and Persia, their mosques becoming symbols of both religious devotion and political authority.

The Great Mosque of Kilwa (further south in present-day Tanzania) and Lamu’s Riyadha Mosque reflected how the coast was stitched into a larger Islamic fabric. Pilgrims traveled to Mecca; scholars circulated Islamic texts in Arabic; qadis (judges) applied Sharia law to settle disputes. Religion fused seamlessly with governance, and the Swahili coast stood as an Islamic zone, distinct from the largely animist or Christian highlands.

When the Portuguese arrived in the 16th century, their conquest of Mombasa was framed as both political and religious. Fort Jesus, looming over the harbor, was less a trading post than a bastion of Christianity in a Muslim land. Its battles with Omani Arabs in the 17th century symbolized Islam’s resilience: though briefly pushed back, coastal Islam emerged stronger when Oman reasserted control, tying Mombasa and Lamu to a vast Omani sultanate centered in Zanzibar.

Islam Meets the Colonial State

By the late 19th century, the British supplanted Omani influence, folding the coast into the East Africa Protectorate. The colonial encounter was awkward. To secure control, the British cut deals with the Sultan of Zanzibar and local Muslim elites, recognizing Islamic courts and property rights on the coast. This created a dual legal system: Africans in the interior subjected to customary law and colonial courts, while coastal Muslims retained elements of Sharia in matters like marriage and inheritance.

This arrangement entrenched a divide. Christianity was privileged inland, where missions and colonial schools thrived. Islam remained coastal, treated as both useful and suspicious — tolerated for stability but marginalized in state investments. Colonial schooling rarely reached Muslim children, leaving them under-educated compared to their Christian counterparts. By independence in 1963, this gap hardened into economic inequality: Muslims were disproportionately poorer, underrepresented in government, and politically peripheral.

Postcolonial Politics and Muslim Identity

At independence, Kenya’s founding elite came largely from Christian backgrounds, especially Kikuyu and Luo leaders of KANU. Coastal Muslims, despite centuries of history, were sidelined in national politics. Their grievances were compounded by land disputes: coastal lands long leased to Arabs and protected by colonial law suddenly became battlegrounds with the new state. Many Muslims feared marginalization not just economically but culturally.

Islam in this era was caught in a paradox: deeply rooted in Swahili culture, yet politically uneasy in a nation dominated by Christian institutions and inland ethnic majorities. While mosques remained centers of community, Muslim leaders struggled to translate faith into political leverage. Some aligned with KANU, others drifted into opposition. Across the 1960s and 1970s, a simmering feeling of exclusion set the stage for collective mobilization.

The Rise of SUPKEM and Political Islam

By the 1970s, Kenyan Muslims had begun to organize formally. The founding of the Supreme Council of Kenya Muslims (SUPKEM) in 1973 marked a turning point. For the first time, Muslims had a national body to advocate for their rights, coordinate education, and serve as the government’s recognized interlocutor. SUPKEM’s creation reflected both state policy (President Jomo Kenyatta preferred to manage Muslim affairs through one umbrella body) and grassroots demand for representation.

SUPKEM provided a voice but also sparked internal debates. Who truly represented Kenya’s Muslims — the coastal Swahili elites, or the growing Somali and Nubian Muslim populations in Nairobi and the north? Should SUPKEM focus on social services and religious affairs, or push harder on political grievances like land and education? These debates mirrored broader tensions within Islam’s Kenyan journey: was it a faith primarily tied to Swahili identity, or a political force spanning diverse communities?

Islam’s Uneasy Position in the State

Through the 1980s and 1990s, Islam in Kenya oscillated between loyalty and marginalization. Coastal Muslims often supported ruling parties to secure patronage but simultaneously decried their exclusion from real power. Education disparities persisted; poverty remained entrenched. In times of political contest — such as the push for multiparty democracy — Muslim grievances were invoked but seldom fully addressed.

The irony was stark. Islam had arrived in Kenya centuries before Christianity, shaped its coast, and embedded itself in its culture. Yet in the postcolonial state, it occupied a liminal position: neither fully embraced nor fully excluded, simultaneously foundational and peripheral.

Conclusion: The Monsoon Winds Still Blow

Today, Kenya’s Muslim population — roughly 10–11% of the country — remains concentrated on the coast and in the northeast. Mosques still dominate old Swahili towns; calls to prayer still punctuate the bustle of Lamu and Mombasa. But the political questions remain unresolved: how to bridge historical inequalities, how to integrate Muslims into national life without erasing their coastal identity, how to reconcile a religion of centuries with a state only decades old.

The story of Islam in Kenya is not one of simple arrival but of shifting winds: from trade to politics, from cultural pride to political marginalization, from Swahili identity to national Muslim advocacy. Like the dhows that first brought it, Islam has continually tacked with the winds of history — surviving, adapting, and insisting on its place in Kenya’s past and future.

Read Next

- The History of Mombasa — From Swahili settlements to Omani sultans and colonial conquest.

- Swahili: The People Who Became the Coast — How Swahili culture formed at the intersection of Africa and Islam.

- The Untold Theology and History of the Akurinu Church — A different strand of faith: indigenous Christianity in central Kenya.

Notes / Sources

- Bethwell A. Ogot (ed.), Zamani: A Survey of East African History.

- Charles Hornsby, Kenya: A History Since Independence.

- Randall Pouwels, Horn and Crescent: Cultural Change and Traditional Islam on the East African Coast.

- Cynthia Hoehler-Fatton, Women of Fire and Spirit: History, Faith, and Gender in Roho Religion in Western Kenya.

- Archival records on the founding of SUPKEM, Government of Kenya (1973).