In the early 19th century, long before colonial railways and highways carved through Kenya, the Akamba (Kamba) people blazed an inland trail from the coast deep into the highlands. Caravans of Kamba traders regularly trekked from Mombasa through the arid Taru Desert into Ukambani (Kamba territory) and beyond, ferrying prized ivory tusks and other goods on the backs of men. These caravans – sometimes 200 or 300 strong – were a common sight at coastal market centers like Rabai and Mombasa, laden with ivory, rhino horn, honey, and beeswax, and only occasionally burdened with human chattel. Unlike other trading peoples of East Africa who grew entangled in the booming slave trade, the Kamba gained renown as traders in commodities rather than captors of men. This is the story of how a stateless caravan society navigated the era of East Africa’s slave trade largely by valuing ivory and cattle over slaves, and how their well-trodden routes inadvertently opened Kenya’s interior to outside commerce – and to would-be slavers.

The Akamba Caravan Trail from Mombasa to Ukambani

From the 1820s onward, Akamba traders developed an elaborate caravan network linking the Kenyan coast to its hinterlands. The main northern route began at the coastal ports of Mombasa (and sometimes Malindi or Tanga) and wound northwest through the Nyika Plateau into Kamba lands. Kamba caravans cut through thorny bush and semi-desert, crossing sparse watering points in places like Taru and Tsavo, before ascending into the cooler highlands of Ukambani and adjacent regions. One branch led toward Mount Kenya and the fertile uplands of the Kikuyu, another toward the Rift Valley and even the Lake Victoria basin. Ivory dominated this inland trade – elephant tusks were “brought from Kitui to Mombasa” by Kamba caravans in great quantity– along with products like animal skins, medicinal herbs, honey, and iron tools. In exchange, coastal merchants provided cloth, beads, copper wire, and firearms, integrating the Akamba into the wider Indian Ocean economy.

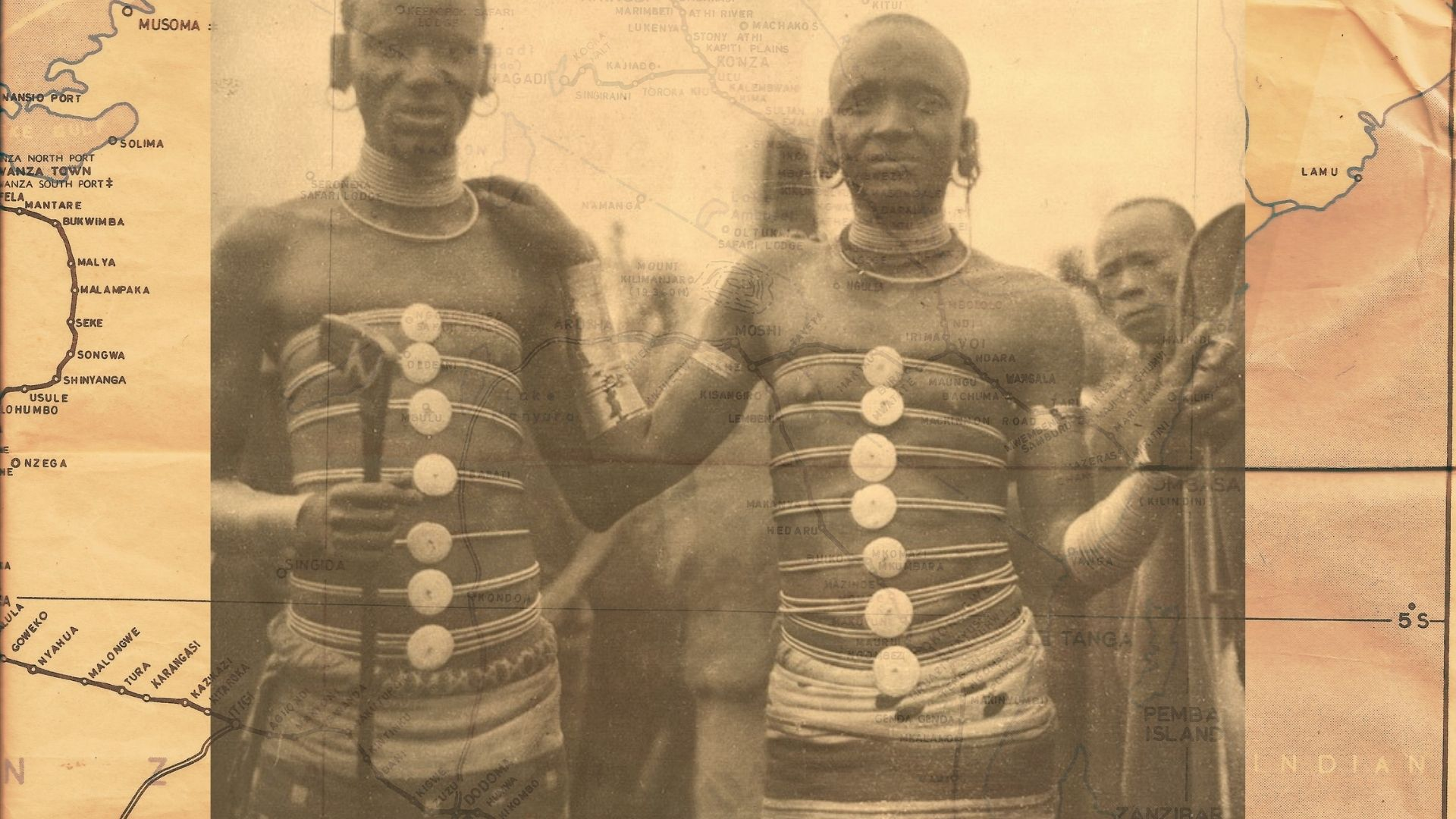

Two Akamba caravan members in traditional attire, overlaid on a map of 19th-century East African trade routes. The Kamba long-distance caravans linked inland communities to coastal ports, with ivory as the primary commodity (map courtesy of African Digital Heritage).

By mid-century, the Akamba had effectively monopolized ivory trading in the Mombasa hinterland. Their hunting parties ranged far: north to Mount Kenya, west into Maasai country, and south across the Tanzanian border, harvesting ivory or bartering for it with interior peoples. Crucially, Kamba territory lay like a gateway between the coast and the deep interior. Outsiders attempting to venture inland often found it safer and more convenient to rely on Kamba middlemen. Missionary Johann Krapf noted that Ukambani “lay like a wall” between coastal traders and elephant-rich districts around Mt. Kenya, so interior peoples preferred handing over ivory to Kamba caravans rather than risk hostile encounters on their own journey to the sea. In large part, then, the flow of goods (and people) from Kenya’s interior to the world beyond depended on Kamba networks. And yet, conspicuously absent from most Akamba caravans were coffles of slaves. This trading people was operating at the height of East Africa’s 19th-century slave trade boom – but they largely shunned the commerce in human beings, setting them apart from other caravan routes in Tanganyika and beyond.

Ivory Over Slaves: Trade Priorities of a Stateless Society

Several factors help explain why the Kamba seldom dealt in slaves even as the demand for enslaved labor in Zanzibar and other markets grew. First, the Akamba were a stateless, decentralized society – they had no kings or powerful chiefs who could easily mobilize raiding armies for slave expeditions. Instead, authority was diffuse: the Kamba were organized into some 20-25 independent clans (utui), and men were regimented by an age-grade system rather than a rigid hierarchy. Councils of elders from the eldest age-grade governed local districts, and decisions were made communally. In such a system, there was no single warlord to orchestrate slave raids on the scale seen in more centralized African kingdoms. This social structure inherently checked the impulse to profit from human trafficking. Indeed, observers noted that slavery was “never a native institution” among the Kamba – they did not traditionally keep slaves as a class of society, nor use slavery as a legal punishment. The idea of capturing and selling large numbers of their fellow Africans was thus somewhat alien to Kamba norms, except in specific wartime contexts.

Equally important were the economic incentives. The Akamba derived enormous wealth from ivory, which by the 1840s–1870s was as lucrative as the human trade (if not more so) and carried fewer risks locally. A single caravan haul of ivory tusks could be exchanged for rifles, cloth, and other foreign goods in high demand. Why risk life and limb raiding heavily defended communities for slaves when one could hunt elephants or trade for ivory instead? Kamba traders became “important in the commercial life of East Africa” through these legitimate goods, remaining so until the dawn of colonial rule in the 1890s. Even when slave prices spiked due to clove plantations in Zanzibar or sugar estates in the Mascarenes, the Kamba showed a relative reluctance. Contemporary testimony from mid-century Zanzibar attested that “They [the Akamba] do not bring slaves, except a few, but trade in ivory”. In other words, coastal merchants knew the Kamba caravans for tusks and hides, not chains of captives. This restraint inadvertently limited the penetration of the slave trade into Kenya’s heartland, at least for a time. While slave raiders devastated populations in what is now Tanzania, Mozambique, and the Congo, much of central Kenya (e.g. the Kikuyu highlands) was comparatively spared the worst of the mid-19th-century slave hunts – due in part to Kamba traders valuing cattle and ivory over slaves and acting as a buffer between coastal slavers and inland tribes.

Raiding Neighbors and “Children of the Bow”

This is not to say the Kamba never engaged in violence or captivity – they did, but in tellingly different ways. Kamba warriors periodically raided neighboring communities such as the Kikuyu, Maasai, and Pokomo, primarily to steal cattle or retaliate against rivals. In these raids, women and children were sometimes taken prisoner. However, instead of marching these captives to the slave market, the Kamba usually assimilated them into their own families. According to one 19th-century observer, “Prisoners are treated well on the whole. The girls become the conquerors’ wives, [and] the captured children are soon looked upon as their own”. Kamba fighters even joked that “These are my children, which I produced with my bow,” humorously acknowledging that the offspring of war could become kin by adoption rather than merchandise for sale. In essence, captured women were absorbed as new wives (bolstering the conquerors’ lineage), and orphaned youngsters were raised as Kamba. This practice of adoption over exploitation stands in sharp contrast to many other African societies where captives might be sold to coastal traders at the first opportunity.

Often, integrating captives served a dual purpose: it increased a family’s labor force and cemented alliances or bloodlines, all without violating the Kamba community’s ethical stance against outright slavery. Yet there were exceptions, especially as the 19th century wore on. If a particular raid yielded more captives than could be easily absorbed – or if an Arab caravan happened to be passing by – “often, however, the prisoners were sold as slaves to the trade caravans from the coast.” Greed or necessity could overrule principle in these instances. Oral traditions and colonial records suggest that some Kamba individuals did sell captives or even people from smaller ethnic groups to Swahili-Arab buyers when the opportunity arose. Such cases, though real, appear to have been comparatively infrequent. Overall, the Kamba slave trade was “probably…insignificant” next to their ivory trade, as historian Gerhard Lindblom concluded. Slaving never became a driving force of the Kamba economy or identity. In fact, when the German explorer Johann Kolle encountered Akamba caravans transporting slaves in the 1880s, it was notable enough to remark upon – a sign that by then a few Kamba had begun dabbling in the illicit trade, even if it remained far from their mainstay.

Chief Kivoi: Trader, Guide, and Unwitting Nation-Namer

One figure embodies the paradox of Kamba involvement in this era of trade and turmoil: Chief Kivoi Mwendwa of Kitui. Born in the late 18th century, Kivoi rose to prominence in the 1830s as one of the premier ivory caravan leaders in Ukambani. By all accounts, he was a master organizer – commanding hundreds of men, establishing caravan stopovers, and negotiating safe passage for his long lines of porters laden with tusks. Kivoi’s chiefdom (more accurately, his personal sphere of influence, since Kamba did not have chiefs in the hereditary sense) sat along the busy route from the interior to Mombasa. In 1849, he achieved historic fame by guiding two European missionaries – Johann Ludwig Krapf and Johannes Rebmann – on a trek inland. It was on this expedition that Krapf, led by Kivoi across the Taru Desert, became the first European to behold Mount Kenya’s snow-capped peak on the equator. When Krapf asked its name, Kivoi’s reply in Kamba, Kiima Kinya (loosely “mountain of whiteness”), would be mispronounced and immortalized by Krapf as “Kenya” – inadvertently giving the country its name.

But Kivoi’s story has a darker side often omitted from heroic narratives. He was also involved in the slave trade, to a degree. Krapf’s journals mention Kivoi keeping a harem of female slaves at his homestead in Kitui to serve as wives or concubines. Local lore (and even modern Kenyan school lessons) claim that “Kivoi sold a lot of slaves to the Arabs”, perhaps even hand-picking the tallest and strongest Kamba youths to profit from. While concrete evidence is sparse, it is clear Kivoi was not entirely immune to the temptations of the human trade. As one recent historian puts it, “he traded mostly in ivory… but he also sold a lot of slaves to the Arabs”. In any case, Kivoi’s fortunes – built on ivory and occasional slave dealing – came to a violent end. On the return leg of the 1849 journey with Krapf, Kivoi’s caravan was ambushed near the Tana River by raiders (possibly Orma or Somali bandits). Krapf recorded the attack in his diary: “The greater part of the caravan was instantly dispersed, Kivoi’s people flying in all directions; Kivoi himself was killed with his immediate followers…”. The Kamba caravan king thus fell victim to the very cycle of plunder that haunted the region. His death sparked anger among his people, who nearly blamed and executed Krapf for leading their leader into disaster. Kivoi today is remembered with mixed legacy – as the intrepid guide who helped put Kenya on the map (literally) and as a symbol of Kamba commercial savvy, but also as a participant in a grim trade that his society as a whole largely resisted.

Arab Caravans Follow Akamba Footprints

Even as the Kamba themselves hesitated to feed the slave trade, their success in opening up routes had an unintended consequence: coastal Arab and Swahili slave traders began using the Akamba caravan trails to penetrate the interior on their own. In the 1850s and 1860s, as demand for slaves surged for clove plantations in Zanzibar and elsewhere, Omani Arab traders realized that collaboration with or emulation of Kamba routes could grant them access to new populations. The Sultan of Zanzibar’s agents had already built relations with the Akamba for ivory trading. But when it became clear the Kamba were not going to supply captives in significant numbers, Arab caravans struck out inland themselves, often guided by Kamba scouts or using Kamba knowledge of the terrain. They traveled from the coast to the interior along the established paths: up from Mombasa to Voi, then west by either skirting Mount Kilimanjaro or cutting northwards into Kamba lands, and onward toward the Great Lakes region. Notably, they avoided the direct northward route through Maasai territory, as Maasai warriors were known to be fiercely protective and had repelled intruders (one Arab caravan was famously massacred by Nandi warriors in 1850 when trying a shortcut). Instead, the slavers prudently “followed the Akamba route” from Voi northwest toward Lake Victoria, moving through friendlier or at least more navigable zones.

By the 1870s and 1880s, reports filtered back of slave caravans in the Kenyan interior – something virtually unseen a few decades earlier. European maps by the late 1880s even depicted a “slave road” running through the southern Kikuyu and Ukambani regions. British abolitionists grew alarmed that the slave trade, long confined to the coast and Tanganyikan routes, was now snaking into Kenya’s highlands. In response, when the Imperial British East Africa Company and later the British government established colonial posts, they deliberately sited some to interdict these inland slave routes. For instance, the British built a fort at Machakos (1889) – in the heart of Ukambani – to oversee the caravan road and ensure any slave traffickers could be stopped. Another outpost at Fort Smith near Kikuyu and a station at Kitui were meant to clamp down on the “new” slave route that bypassed the well-patrolled Mombasa-to-Uganda road. As one account notes, “Machakos [was founded] so that the slave traffic between the Lake and the coast could be supervised… Kitui too was occupied to enable the Government to check slave caravans.” Arab-Swahili traders had turned to the Akamba trail as a safer alternative, but the British moves closed the window, effectively strangling the last vestiges of the overland slave trade by the 1890s.

It is worth emphasizing that even during this period, the Kamba themselves were not enthusiastic accomplices of the slavers. Some Kamba did act as porters or guides for Arab-led caravans (economic reality often trumped morals when hunger loomed), and a handful of Kamba elites profited quietly by selling people to coastal buyers. Yet these were exceptions that proved the rule. On the whole, the Kamba reputation in the 19th century remained that of honest caravan traders, valued by foreigners for their reliability and feared for their skill with bow and poison arrow, but not despised as slave raiders the way the Yao or Nyamwezi came to be. In fact, some African communities later recalled the Akamba in positive terms for this reason. The peoples of what is now Tanzania, for example, distinguished between the hated “Yao slave dealers” and traders like the Kamba who were interested in ivory and trade goods, not human plunder. By inadvertently stalling the eastward expansion of the slave trade, the Kamba caravan network allowed large parts of Kenya to escape depopulation and social collapse during the mid-1800s – a “lesser-known dynamic” of resistance amid a tragic era.

Legacy of the Caravan Network in Modern Kenya

The imprint of the 19th-century Kamba caravan routes can still be traced in Kenya’s geography and society today. Many modern roads and rail lines follow the very paths beaten by Kamba caravans two centuries ago. The Mombasa-Nairobi highway, for instance, runs through Voi, Kibwezi, and Machakos – all waypoints or offshoots of the old caravan trail. It’s no coincidence that the Uganda Railway (built in the 1890s) and the later highways chose these corridors: they were the gentlest gradients and most established routes, thanks to generations of Kamba and Swahili porters who first figured them out. Rabai, the mission station near Mombasa where Krapf based himself, was originally a Kamba caravan terminus – a place where by 1850 Kamba traders had settled after fleeing a famine, maintaining a village to facilitate commerce with the coast. Even today, Rabai’s community retains memories of those first Kamba “foreigners” who came for trade and stayed, their descendants assimilated into the coastal culture. The town of Voi, a crucial watering point before the climb into the highlands, is by local tradition named after Chief Kivoi (pronounced ‘Ki-voi’), who supposedly established a large boma (homestead) there as a caravan rest stop. While historians debate the exact origin of the name, the legend attests to how deeply the caravan era is woven into local lore – Kivoi is regarded as a national figure, both celebrated and controversial, for his role in shaping Kenya’s early interactions with the outside world.

Culturally, the Kamba have retained a pride in their ancestors’ reputation as astute traders and trailblazers. Oral histories recount how “the Kamba opened the way” for both goods and (unwittingly) Europeans to enter Kenya’s interior. There is also a measure of pride that, unlike some neighbors, the Kamba did not sell their own into slavery en masse. This narrative of cultural resistance – a community that valued kinship and humane integration of captives, thereby resisting the worst instincts of the slave trade – has been highlighted in recent scholarly works and heritage projects. For example, digital archives now document how Omani Arabs “came to use the Akamba’s routes to head towards the hinterland to capture people as slaves,” implying the Kamba themselves were not the ones doing the capturing. Such projects shed light on the legacy of stateless societies vs. the slave trade, illustrating that not all African peoples exploited the slave economy to its fullest; some, like the Kamba, chose a different path (literally and figuratively). The very term used by inland communities for the coastal caravans – mutukumi or “slave raiders” – was never applied to the Kamba caravans, indicating a level of trust or at least distinction.

Meanwhile, the consequences of the Kamba focus on ivory over slaves had other reverberations. Elephants in Kenya suffered heavy losses during those years, as Kamba and others hunted prodigiously to meet the ivory demand. The environmental and ecological legacy of the caravan trade includes this wildlife depletion. And when the caravan era gave way to colonial rule, the Kamba found that their age-old trading livelihood was disrupted – the British railroad and administration ended the long-distance caravan commerce by 1900. Many Kamba, facing the loss of the trading economy and pressures of land degradation at home, turned to other work (including serving as soldiers and laborers for the British in the 20th century). Yet, the memory of their caravan routes did not vanish. Today, one can still travel portions of the old “Uganda Road” – essentially the route Kamba caravans pioneered – and find traces of caravan stopovers: old wells at Tsavo, stories of camps at Kibwezi, the grave of a trader here, the ruins of a rest house there.

In sum, the Akamba caravan route stands as a remarkable chapter in East African history. It was a network built by a segmentary, acephalous society that nonetheless managed to dominate regional commerce for decades. It ferried ivory and iron but only rarely humans, thereby slowing the eastward spread of slave trafficking into the Kenyan highlands almost by accident. And it set the stage for later incursions – missionaries, explorers, colonizers – who quite literally followed in the footsteps of Kamba caravans. To retrace this route today, from the sweltering humidity of Mombasa, through the dry plains of Taru, past the town named for Kivoi, up into the green hills of Ukambani, is to walk in the shadows of both commerce and humanity: ivory paths that sometimes carried lost captives, a trail of exchange that illuminated how an African people can engage with global trade while mostly refusing to trade in their fellow humans. It is a journey that illuminates trade routes, cultural resistance, inland–coastal links, and the lasting legacy of a caravan network that made history by choosing ivory over slaves.