In East Africa, running has never been just sport—it has always been a statement of identity. From the red tracks of Kampala to the highland trails of Eldoret, every stride carries echoes of history, pride, and rivalry. To run for Kenya, Uganda, Tanzania, or Ethiopia was to declare more than speed. It was to prove which nation held the endurance of the mountains, the lungs of the Rift Valley, and the will to outlast the world.

Athletics became the region’s most enduring form of diplomacy. Before presidents shook hands or borders were drawn, runners were already crossing them, testing one another on dirt and cinder. The greatest track battles of all time in East Africa were not mere contests of muscle—they were the region’s dialogue about nationhood, dignity, and destiny.

Kenya, with its deep bench of champions, stood at the center of this history. From Kipchoge Keino’s grace in the 1960s to Faith Kipyegon’s unmatched records today, Kenya became synonymous with endurance. Yet its supremacy was never unchallenged. Across the border in Uganda, Tanzania, and Ethiopia, rivals rose who turned every race into a test of will and pride.

This is the story of those rivalries—the neighborly duels that built Kenya’s athletic empire, tested its mythology, and defined East African sport for half a century.

Kenya vs Uganda: Brothers and Rivals in the Highlands

If Kenya’s running identity was born in the Rift Valley, its first great test came from across the border in Uganda. The rivalry between the two nations has always been brotherly, built on shared languages, intermarried clans, and even shared training camps. But on the track, that brotherhood turned to fire.

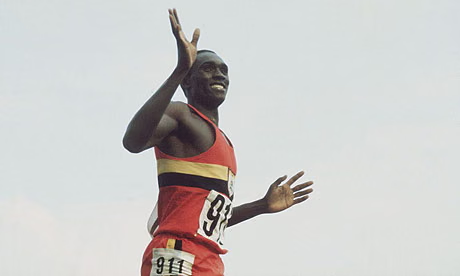

The story begins in 1972, when John Akii-Bua, a police officer from Lango, stunned the world at the Munich Olympics. Running in lane one—the tightest and least favored—he stormed to victory in the 400m hurdles, clocking a world record of 47.82 seconds. No African had ever done such a thing before. His triumph forced Kenya, then dominant in middle and long distances, to reckon with Uganda’s sudden burst of sprinting brilliance.

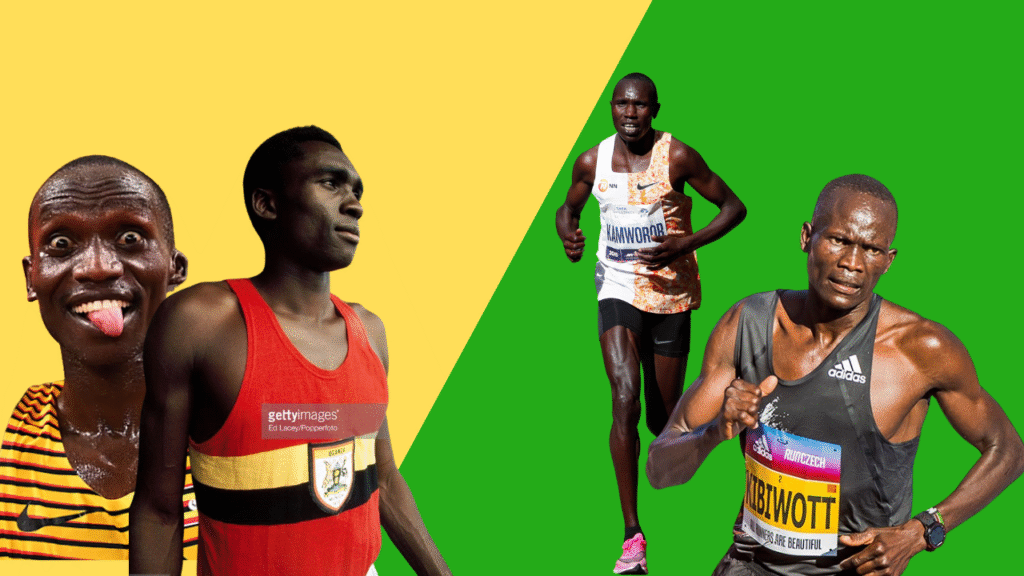

Kenya responded in its own way: through endurance. In the 1970s and 1980s, Kenyan runners began sweeping the 5,000m and 10,000m events while Uganda sought to close the gap. The most symbolic of these clashes came decades later at the 2017 IAAF World Cross Country Championships in Kampala. Before a home crowd roaring with pride, Uganda’s Joshua Cheptegei led the men’s senior race from start to nearly the finish—until exhaustion struck in the final stretch. Kenya’s Geoffrey Kamworor surged past him to claim gold, as Cheptegei staggered across the line to finish thirtieth.

That heartbreak became Uganda’s turning point. Two years later, Cheptegei returned at the 2019 World Cross Country Championships in Aarhus, Denmark, to defeat Kenya’s Kibiwott Kandie and Geoffrey Kipsang, reclaiming East Africa’s honor for Uganda. In 2020, he broke the 5,000m and 10,000m world records, signaling that Uganda had matured from Kenya’s apprentice to its most dangerous rival.

Yet beneath the rivalry lies deep kinship. Many Ugandan champions, including Stephen Kiprotich, the 2012 Olympic marathon gold medalist, trained in Kenya’s Eldoret and Kaptagat camps. Likewise, Kenyan coaches have long crossed the border to nurture Ugandan talent. The two nations share not only altitude and physiology but an intertwined sense of purpose: to keep the world’s fastest runners East African.

In truth, Kenya vs Uganda has always been a family affair—a duel where victory and defeat are both celebrated in the same breath. As Akii-Bua once said in a BBC interview before his death in 1997, “When I beat the Kenyans, they clapped for me. When they beat me, I clapped for them. We are brothers in sweat.”

Kenya vs Tanzania: The Bayi and Nyambui Years (1974–1980)

If the rivalry with Uganda was familial, the one with Tanzania was philosophical. It was not just a contest of runners, but of ideologies. In the 1970s, Kenya and Tanzania stood for two competing visions of postcolonial Africa: capitalist pragmatism under Jomo Kenyatta and later Daniel arap Moi, versus socialist idealism under Julius Nyerere’s Ujamaa policy. On the track, those political differences found their poetry in the legs of men who ran like they carried nations on their backs.

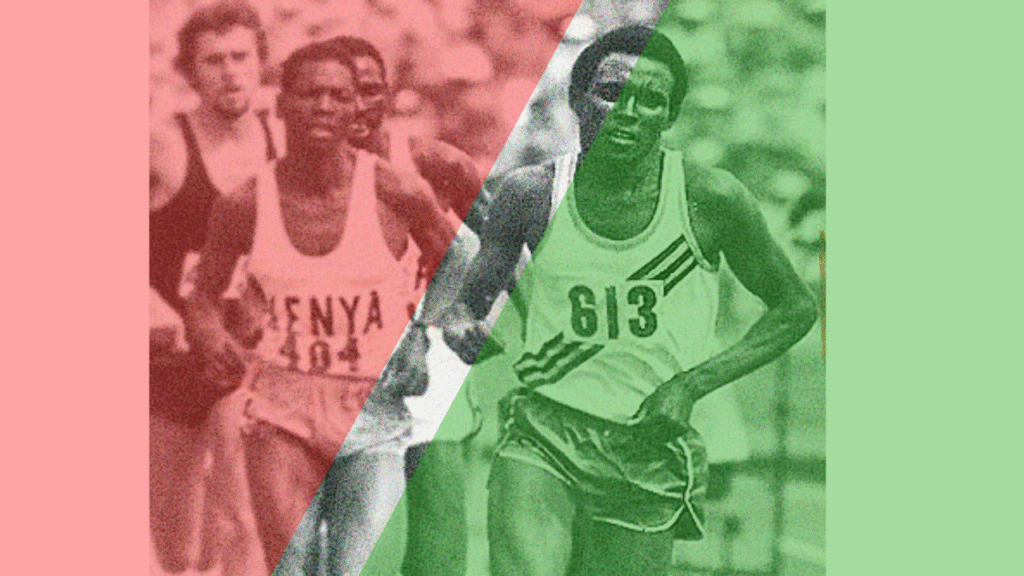

The drama began in 1974 at the Commonwealth Games in Christchurch, New Zealand. Kenya had long dominated middle-distance running. Then came Filbert Bayi, a tall, fearless Tanzanian soldier known for front-running—a style considered suicidal by conventional coaches. In the 1500m final, Bayi sprinted from the gun, forcing the field into a desperate chase. Kenya’s Ben Jipcho, one of the most tactical runners of his generation, tried to close the gap. But Bayi never relented. He broke the tape in 3:32.16, shattering the world record and defeating Jipcho by nearly two seconds.

For Kenya, that loss was more than a race—it was a bruise to national pride. Bayi’s victory was Tanzania’s declaration that the balance of power in East African athletics was shifting. Newspapers in Dar es Salaam hailed him as the “Lion of Africa,” while in Nairobi, editorials grudgingly admired his audacity.

Bayi’s legacy extended beyond the stopwatch. His triumph came at a time when Tanzania’s socialist state was emphasizing self-reliance and cultural pride. He became a national symbol of Ujamaa strength—a man who could defeat Kenya’s professionalized, army-trained runners with little more than discipline and belief. His success inspired a new generation, among them Suleiman Nyambui, who carried the flag through the late 1970s and early 1980s.

Nyambui, a university student in the United States, refined Tanzania’s dominance in the 5,000m and 10,000m events. At the 1980 Moscow Olympics, he won silver in the 5,000m behind Ethiopia’s Miruts Yifter—an achievement that made Tanzania, briefly, a serious threat to Kenya’s supremacy. His duels with Kenya’s Henry Rono and Mike Musyoki on the international circuit brought East African rivalry to the global stage.

But by the mid-1980s, Kenya reclaimed the crown. Henry Rono’s unprecedented four world records in 81 days in 1978—spanning the 3,000m, 5,000m, 10,000m, and steeplechase—silenced doubts about Kenya’s endurance empire. The Kenyan response was emphatic: while Tanzania’s stars were individuals, Kenya’s success came from system and scale. The disciplined training camps of Iten, Kapsabet, and Kaptagat ensured a conveyor belt of talent, while political stability enabled steady support for sport.

By the time Bayi and Nyambui retired, the rivalry had cooled, but the memory of those years lingered. They marked the only period in history when Tanzania truly outshone Kenya on the track, when the roar of Dar es Salaam drowned the cheers from Eldoret. It was also a rare moment when ideology met athletics—when the stopwatch became a referendum on how Africa should develop.

Today, Tanzanian athletes still invoke Bayi’s name as a challenge to complacency. Every time a Kenyan runner glances over his shoulder and sees a Tanzanian closing in, he is reminded of 1974—the year a man from Morogoro ran away from history and made the Rift Valley chase him.

Kenya vs Ethiopia: The Eternal Duel of the Highlands

No rivalry in world athletics carries as much mystique—or endurance—as the one between Kenya and Ethiopia. It is a saga that has spanned more than half a century, unfolding across generations and continents. The two nations share the same high-altitude geography and pastoral traditions, yet their rivalry is as much spiritual as it is physical. It is a contest between two civilizations of endurance—the runners of the Great Rift Valley against the runners of the Ethiopian plateau.

The story begins not in Kenya, but in Rome, 1960, when Ethiopia’s Abebe Bikila won the marathon barefoot, running under the glow of street lamps that once lit the Roman Empire. His victory was more than athletic—it was political. Africa had begun to break free from colonial chains, and Bikila’s triumph symbolized independence through discipline. Kenya’s future runners watched him as a revelation. As Kipchoge Keino later recalled in an interview, “Bikila showed us that Africa could run with dignity.”

By the time Keino burst onto the global stage at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, the balance had begun to tilt. His victory in the 1500m, achieved after outsmarting world record-holder Jim Ryun, announced Kenya’s arrival as Ethiopia’s equal. Over the next two decades, the battle shifted back and forth. When Kenya produced Henry Rono and Samson Kimobwa, Ethiopia answered with Miruts Yifter, the “Yifter the Shifter,” whose devastating finishing sprint earned him two Olympic golds in 1980.

The 1990s and 2000s brought the rivalry to its golden age. Ethiopia’s Haile Gebrselassie emerged as the quintessential tactician—his elegant stride and psychological composure made him unbeatable in the 10,000m. Kenya countered with Paul Tergat, a military man whose grit and patience turned every final lap into a duel of wills. Their clashes became the stuff of legend: the Sydney 2000 Olympics, where Gebrselassie beat Tergat by a mere 0.09 seconds, remains one of the greatest races in Olympic history.

Tergat would later exact his revenge on the roads, breaking the marathon world record in 2003, paving the way for a new Kenyan generation led by Eliud Kipchoge. Yet even as Kipchoge ascended to global dominance, Ethiopia found new heirs in Kenenisa Bekele, Tirunesh Dibaba, and Meseret Defar. The rivalry expanded to include women’s events, where Kenya’s Vivian Cheruiyot, Brigid Kosgei, and Faith Kipyegon battled Ethiopia’s elite across world championships and Olympic finals.

What makes Kenya vs Ethiopia more than sport is its continuity. Unlike fleeting rivalries, it renews itself every decade. When one star fades, another rises on either side. When Kenya refines its altitude training camps, Ethiopia counters with cultural discipline drawn from monastic endurance. Both nations see running not as entertainment but as heritage—an inheritance from ancestors who survived by walking vast distances.

The rivalry also carries symbolic unity. At the 1997 World Cross-Country Championships in Turin, Italian reporters were astonished to see Kenyan and Ethiopian athletes training together before the race, laughing and sharing meals. Yet, come race day, they fought as though the fate of the continent depended on it. In that moment, East Africa’s paradox was visible: fierce rivalry built on mutual respect, competition sustained by kinship.

Mbiti (1975) once described African life as a circle where “the individual exists only in relation to others.” The Kenyan–Ethiopian rivalry captures that truth on a global stage. Each side pushes the other to transcend limits, ensuring that the highlands of Africa remain the heartbeat of distance running.

When the gun sounds, it is no longer just a start—it is history awakening. From Bikila’s bare feet to Keino’s gallop, from Gebrselassie’s smile to Kipchoge’s composure, Kenya and Ethiopia continue to race not for dominance but for legacy: who will define what endurance means to the world?

Kenya vs the World: When the Rift Valley Conquered the Globe

By the late 1960s, Kenya’s runners had already turned the region’s dirt trails into launchpads to the world. The early years of independence coincided with the golden age of athletics—when running became both soft power and cultural expression. To win was to declare that a small African nation could redefine human endurance. From that moment, Kenya’s rivalry was no longer confined to East Africa. It was now Kenya versus the world.

The turning point came at the 1968 Mexico City Olympics, held at high altitude. The conditions favored those who lived and trained in thin air, and no one embodied that advantage like Kipchoge Keino. In one of the most iconic races in Olympic history, Keino defeated world record holder Jim Ryun of the United States in the 1500 meters, running a blistering pace despite a severe gallbladder infection. That victory made Keino not only a national hero but a continental symbol. In the same Games, Naftali Temu won gold in the 10,000m, cementing Kenya’s arrival as a new athletic superpower.

By the 1970s and 1980s, Kenyan runners dominated both the track and the roads. When nations like Britain, the United States, and Australia assembled elite distance squads, they often did so to figure out one question—how to beat Kenya. The answer, for decades, was elusive. Kenyan runners, most trained in rural schools or police and army camps, brought a mix of humility, teamwork, and tactical discipline rarely seen elsewhere.

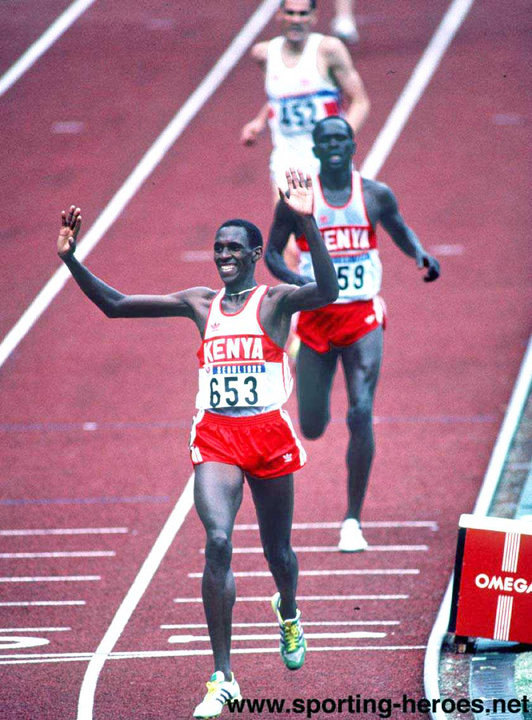

In the 1988 Seoul Olympics, Julius Kariuki and Peter Koech delivered a 1–2 finish in the 3000m steeplechase, an event Kenya has owned ever since. The discipline became a national signature, its rhythm echoing the country’s mixture of strategy and endurance. Over the years, steeplechase legends like Moses Kiptanui, Ezekiel Kemboi, and Conseslus Kipruto extended that dominance, transforming the event into a symbol of Kenyan identity.

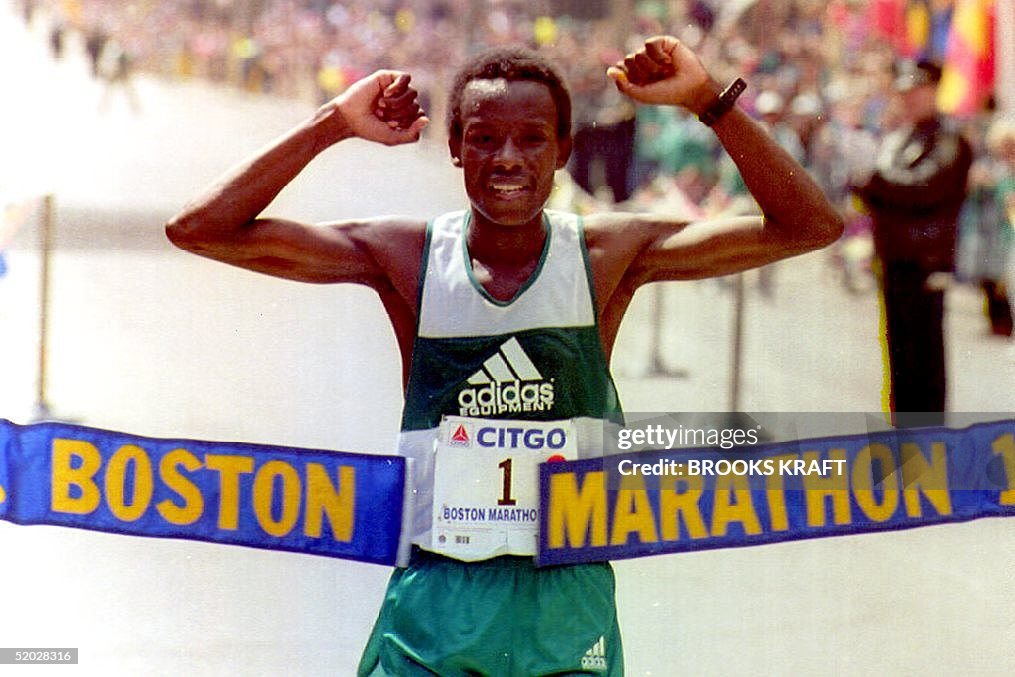

By the 1990s, Kenyan runners had shifted the rivalry to the marathon, turning the streets of London, Boston, and Berlin into their new battlefield. Douglas Wakiihuri, Ibrahim Hussein, and Tegla Loroupe led the charge, showing that Kenya’s endurance could conquer even asphalt and city smog. Loroupe, in particular, became a pioneer—she was the first African woman to win both the New York and Berlin marathons, and her success inspired an entire generation of women to take up competitive running.

Then came Eliud Kipchoge, whose calm demeanor and perfectionist discipline transformed the marathon into an art form. His sub-two-hour run in Vienna in 2019 was not recognized as an official world record, but it transcended record books altogether. “No human is limited,” he said afterward—a phrase that carried the same revolutionary spirit as Keino’s 1968 victory. Kipchoge’s feat confirmed what the world had already known for decades: that Kenya’s runners had redefined the limits of the possible.

Kenya’s duels with global powers have never been simple contests of pace. They’ve been cultural statements. Against the United States, Kenya represented a quiet, collective ethos over individual glory. Against Europe, it symbolized endurance born from necessity rather than privilege. Against the rising oil-rich Gulf states, which now recruit African-born athletes under new flags, Kenya’s challenge is moral as much as physical—preserving authenticity in a globalized sports economy.

Through it all, Kenyan runners have kept one enduring tradition: humility in victory. Whether at the Olympics or city marathons, they celebrate by pointing skyward, not beating their chests. As Keino once told reporters in 1972, “We do not run to prove we are better than anyone. We run to remind the world what effort and faith can do.”

Half a century later, that philosophy still defines Kenya’s rivalry with the world. From the dusty paths of Iten to the gold-plated finish lines of Berlin, Kenyan runners remain global ambassadors of discipline, resilience, and grace. They have turned endurance into diplomacy—and running into one of the most powerful symbols of a nation’s character.

Running as Nationhood

In Kenya, running became more than a sport; it became the country’s purest expression of self. From the first Olympic medals in the 1960s to the global dominance that followed, athletics turned into a language through which Kenyans articulated unity, pride, and possibility. The early independence governments quickly realized what the British Empire had once underestimated—that running could build national identity faster than any speech or manifesto.

Schools across the Rift Valley—Kapsabet, St. Patrick’s Iten, and Tambach—became seedbeds of this identity. Their training programs mirrored the national ideal of Harambee—“pulling together.” Coaches like Brother Colm O’Connell and coaches in police and army units treated running as civic duty. The government’s sports institutions, including the Armed Forces and Kenya Prisons teams, built discipline, teamwork, and patriotism into training regimens. Winning was no longer personal; it was service.

Every great Kenyan victory carried echoes of the country’s history. When Kipchoge Keino lifted his medal in Mexico City, he did so as a representative of a newly independent state. When Henry Rono shattered four world records in 1978, he embodied the resilience of a nation weathering political and economic strain. When Tegla Loroupe became a global ambassador for peace through sport, she showed how the moral values of Kenyan running—humility, endurance, and respect—could transcend borders.

Even defeat became part of the national story. In the 2000 Sydney Olympics, when Paul Tergat narrowly lost to Haile Gebrselassie, Kenyans mourned as if they had lost a brother, not just a race. But that loss reinforced a deeper truth: Kenya’s greatness came not from invincibility, but from persistence. Running, for Kenya, was not a contest of supremacy but a ritual of becoming—a constant pursuit of betterment that mirrored the country’s collective struggle for progress.

As historian John Bale observed, Kenyan runners “run for home even when they are abroad.” The track became a moving homeland, each stride reaffirming identity. Whether competing in Oslo or Doha, Kenya’s red, green, and black flag symbolized endurance born of struggle, dignity forged in motion.

Legacy and the Future

The rivalries that shaped East African running—Kenya versus Uganda, Tanzania, Ethiopia, and the world—continue to evolve. New names now carry the legacy: Faith Kipyegon, Ferdinand Omanyala, Beatrice Chebet, Jacob Kiplimo, and Letesenbet Gidey. The competition remains fierce, but the spirit remains communal.

Modern Kenyan athletics faces new challenges. Globalization has blurred national lines, as wealthy nations recruit African-born athletes, offering citizenship in exchange for medals. Doping scandals and mismanagement threaten to stain the purity of Kenya’s reputation. Yet, beneath the noise, the moral essence of Kenyan running endures—the belief that talent must serve society.

Every dawn in Iten or Kaptagat, hundreds of young athletes still lace up their shoes and run through the mist. They chase dreams, yes, but also something larger: the unbroken rhythm of history. Their feet drum the same earth as Keino’s, Rono’s, and Kipchoge’s. In their breath lives the continuity of a national faith—faith in work, in endurance, and in the idea that no human is limited.

The story of Kenya versus its neighbors is, ultimately, the story of East Africa itself—a region bound by altitude, bloodlines, and belief. Its runners have turned the tracks of the world into parables of cooperation and competition. In victory or defeat, they remind us that greatness is not measured by records alone, but by how far one nation can carry its spirit through the centuries.

Kenya’s greatest rival has never been another flag—it has always been time. And for more than half a century, the runners of the highlands have been winning that race.

References

Bale, J. (2004). Running cultures: Racing in time and space. London: Routledge.

Mbiti, J. S. (1975). Introduction to African religion. London: Heinemann.

Wallechinsky, D., & Loucky, J. (2012). The complete book of the Olympics: 2012 edition. London: Aurum Press.

Wigglesworth, N. (2020). The long distance runner: Athletics, identity, and East Africa. Nairobi: Kenya Literature Bureau.