Early Life and Education

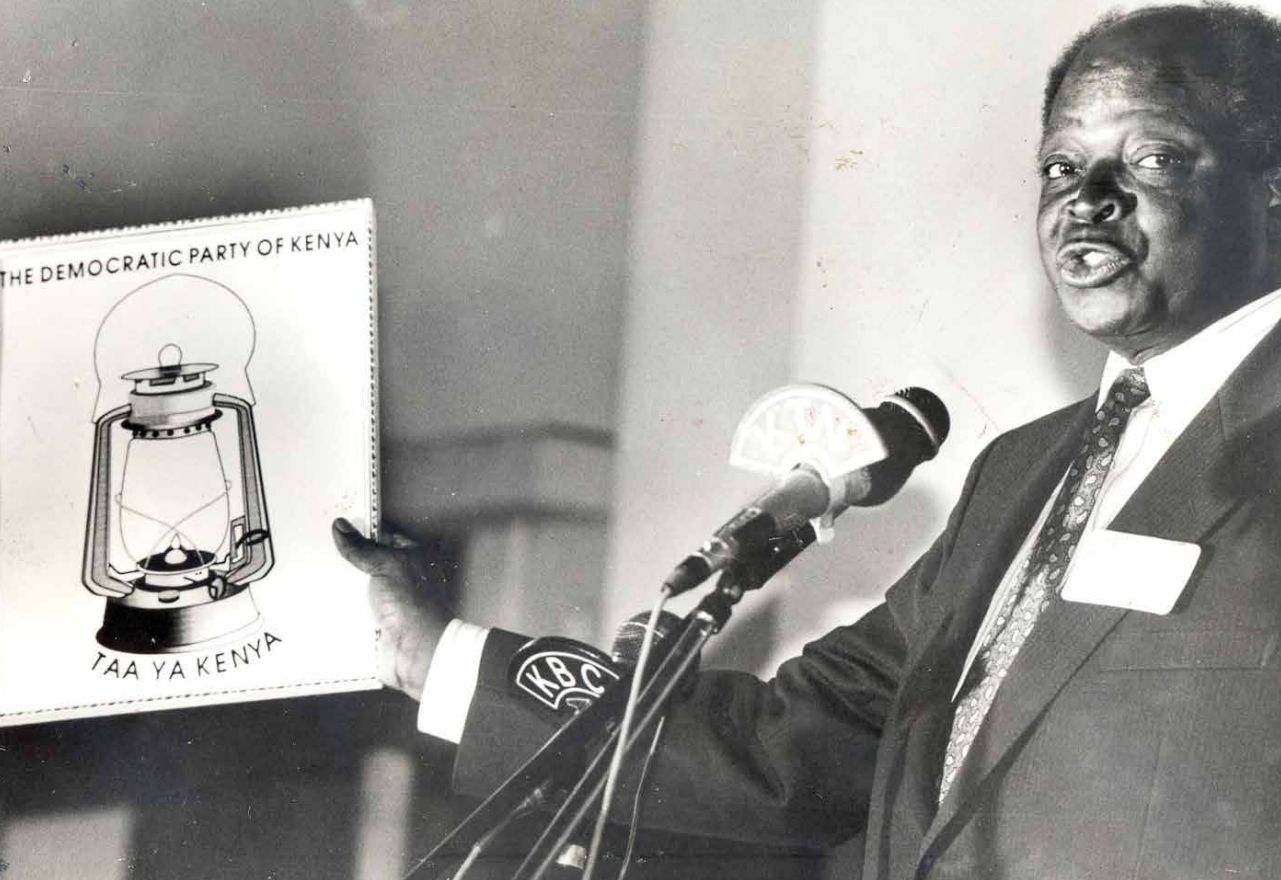

Mwai Kibaki was born on November 15, 1931, in Gatuyaini village in Kenya’s central highlands, the youngest of eight children in a farming family. Showing academic promise, Kibaki attended top local schools before earning a scholarship to Makerere University in Uganda, where he studied economics, history, and political science, graduating in 1955 with first-class honors (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025). He then went on to the London School of Economics, becoming the first East African to achieve a first-class degree at that institution (Miriri, 2022reuters.com). After university, Kibaki briefly worked as an assistant economics lecturer at Makerere in the late 1950s. During this period, he became involved in drafting independent Kenya’s first constitution, signaling an early entry into politics (Columbia University, 2010worldleaders.columbia.eduworldleaders.columbia.edu).

Rise in Politics: From Independence to Vice Presidency

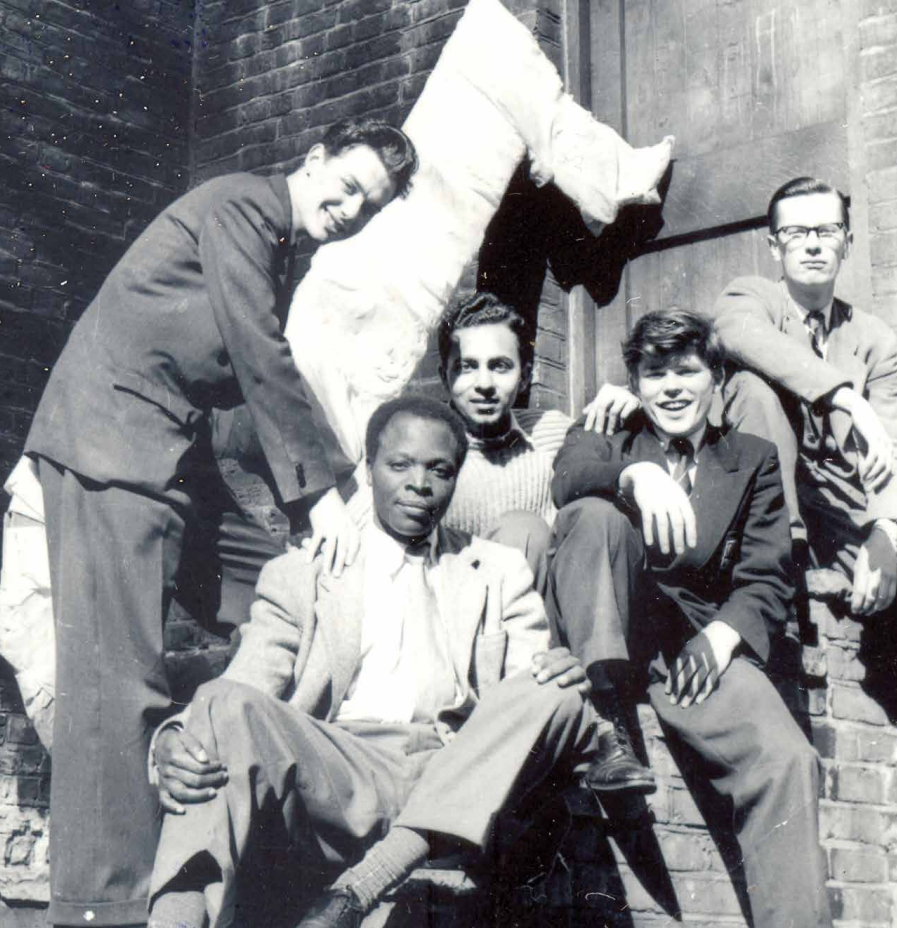

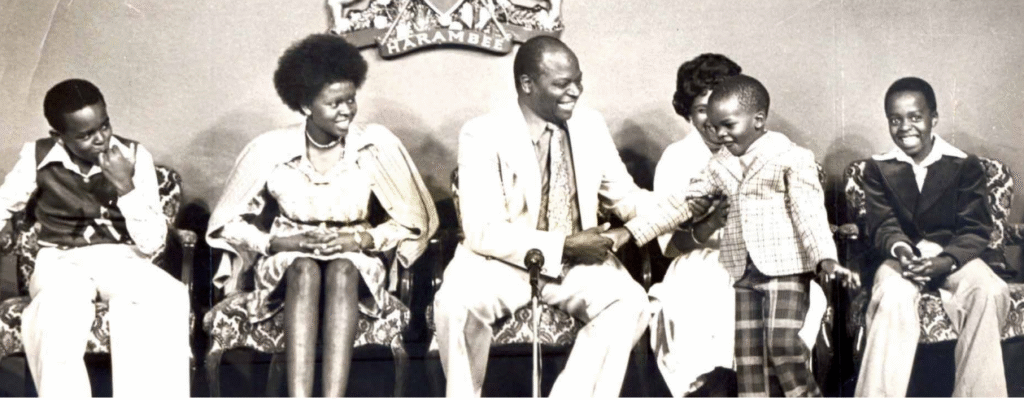

Following Kenya’s independence in 1963, Kibaki won a seat in the National Assembly as a member of the Kenya African National Union (KANU), the dominant party of Jomo Kenyatta (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025britannica.com). He quickly rose through the ranks due to his technocratic acumen. Under President Kenyatta, Kibaki was appointed Parliamentary Secretary in the Treasury and later served as Minister of Commerce and Industry by 1966 (Sisi Afrika, 2022sisiafrika.com). In 1969, he was elevated to Minister of Finance and Economic Planning, a powerful post he would hold for over a decade (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025britannica.com).

When Daniel arap Moi took over after Kenyatta’s death in 1978, Kibaki was named Vice President. He served as Kenya’s Vice President from 1978 to 1988 while also holding other cabinet portfolios, including a continued stint as Finance Minister until 1982 (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025britannica.com). During these years, Kibaki gained a reputation as a brilliant economist and civil servant, but also as a loyal insider to the ruling establishment. Notably, he was responsible for moving the 1982 constitutional amendment that formally made Kenya a one-party state under KANU – a decision reflecting his alignment with the authoritarian status quo of the time (Sisi Afrika, 2022sisiafrika.com). Critics later dubbed him a “general coward” for shying away from confrontational reform, as he often preferred consensus and gradual change over bold dissent (Sisi Afrika, 2022sisiafrika.com). Nonetheless, Kibaki’s technocratic skill was evident; under his management, Kenya experienced periods of economic stability in the 1970s, although the late 1970s oil shocks and mismanagement later slowed growth (Gathara, 2022aljazeera.com).

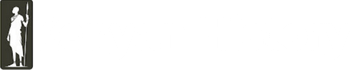

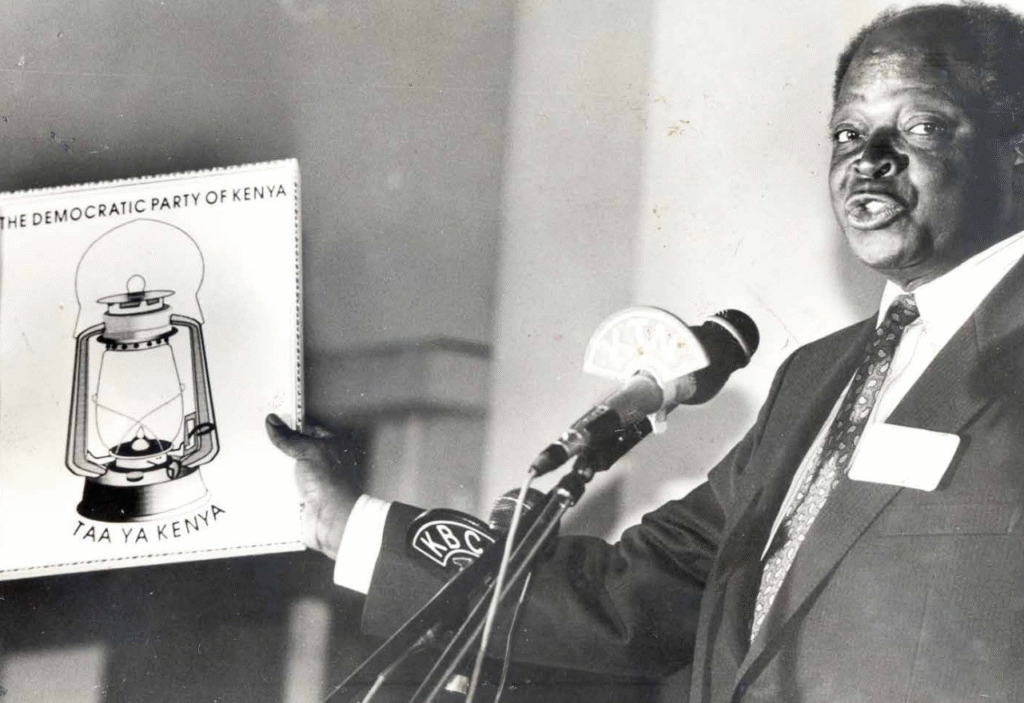

By the late 1980s, Kibaki’s relationship with President Moi had cooled. In 1988, Moi demoted Kibaki from the vice presidency to a lesser cabinet post (Minister of Health), a clear sign of waning favor. As agitation for multiparty democracy grew in Kenya, Kibaki initially dismissed the proponents of political pluralism – famously quipping in 1990 that ousting KANU was like “trying to cut down a fig tree with a razor blade” (Sisi Afrika, 2022sisiafrika.com). However, after internal and external pressures forced Moi to repeal the one-party rule in 1991, Kibaki made a pragmatic pivot. He resigned from KANU in December 1991 and founded the Democratic Party (DP) to compete in the new multiparty system (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025britannica.com). This move reflected Kibaki’s calculated political instinct: he was quick to take advantage of reforms he had once been slow to support, positioning himself to lead in the emerging democratic space.

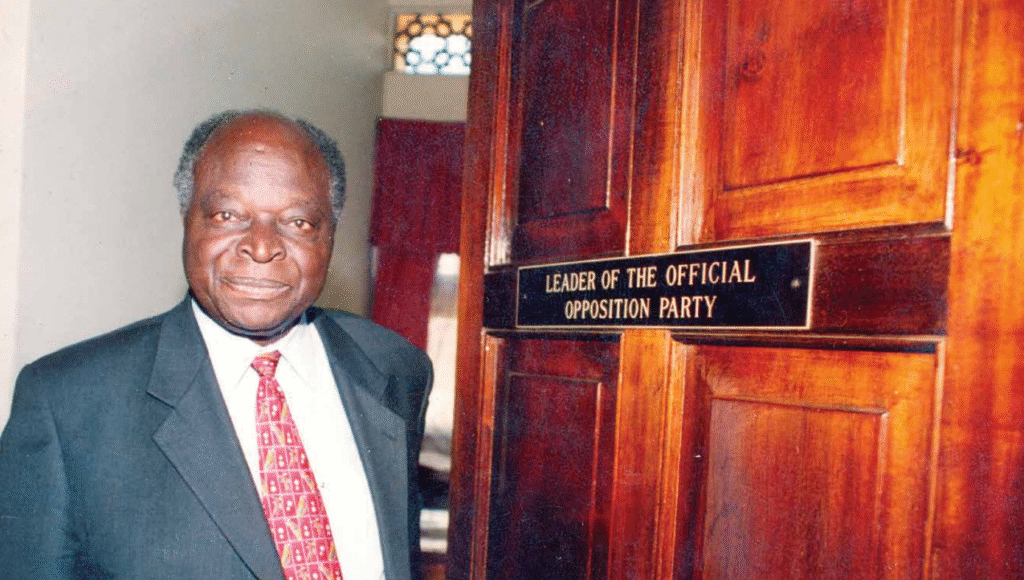

Leader of the Opposition (1992–2002)

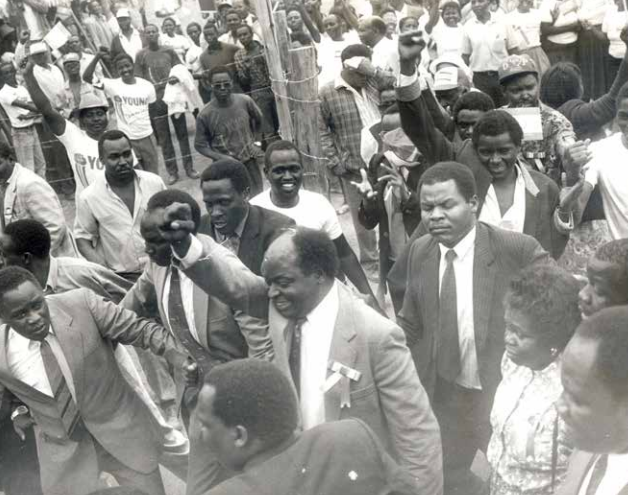

Kibaki ran for president under the DP banner in Kenya’s first multiparty elections in 1992. He finished third in that race, and again lost in 1997, when he was runner-up to Moi. Despite these defeats, Kibaki solidified his position as a leading opposition figure. In 1998 he became the official Leader of the Opposition in Parliament, as DP held the second-highest number of seats after KANU (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025britannica.com). During the 1990s, Kibaki’s opposition stance was notably moderate and policy-focused compared to some of his more fiery contemporaries. He projected the image of a genteel, experienced statesman – at times criticized as too bland or cautious, but also respected for his deep knowledge of government.

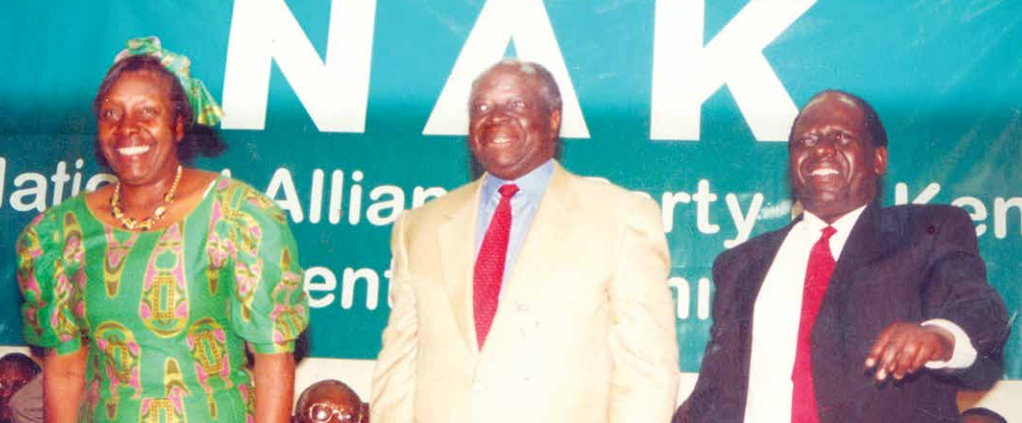

By 2002, with President Moi constitutionally barred from another term, Kibaki joined forces with a broad alliance of opposition parties to finally unseat KANU. He helped form the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC), a multiethnic, multiparty alliance united behind the goal of reform. Late in the campaign, Kibaki was seriously injured in a car accident, requiring him to campaign from a wheelchair in the final stretch (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025britannica.com).

Despite his physical frailty at the time, NARC’s message of change resonated across Kenya. Backed by key lieutenants such as Raila Odinga – who popularized the slogan “Kibaki Tosha” (“Kibaki is enough”) to rally support – Kibaki led NARC to a landslide victory. In the December 2002 election, he defeated Moi’s chosen successor, Uhuru Kenyatta, by a wide margin, and NARC won a majority in parliament, ending KANU’s 39-year grip on power (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025britannica.com).

Kibaki’s inauguration on December 30, 2002, was met with nationwide euphoria. Speaking to an ecstatic crowd while still wheelchair-bound and clad in a leg cast, he promised a “clean break” from the autocratic and corrupt practices of the past regime (Miriri, 2022reuters.com). The optimism was palpable; Kenyans, who had known only one-party rule under Kenyatta and Moi, greeted Kibaki’s presidency as the dawn of a new era of democracy and economic revival.

Presidency (2002–2013) – Reforms and Achievements

Economic Revival and Free Education: President Kibaki’s first term (2002–2007) focused on undoing the economic stagnation of the Moi era. An experienced economist, Kibaki championed market-friendly policies, fiscal reforms, and public investments to jump-start growth. The results were soon evident: Kenya’s GDP growth climbed from a meager 0.4% in 2002 to about 6–7% by 2007, marking one of the country’s most rapid economic turnarounds in history (Ministry of Defence, n.d.mod.go.ke). This growth was underpinned by a stable macroeconomic environment, including lower inflation and increased revenues, as well as renewed donor confidence in Kenya’s governance. Kibaki’s administration enacted an Economic Recovery Strategy that prioritized key sectors like agriculture, tourism, and manufacturing, which rebounded strongly in the mid-2000s. By 2006, for example, Kenya’s economy was expanding at over 6% annually, compared to near-zero growth at the start of the decade (Reuters, 2007reuters.com).

One of Kibaki’s hallmark policies was the introduction of Free Primary Education in 2003. Fulfilling a major campaign promise, his government abolished tuition fees in all public primary schools. The impact was immediate: within weeks, an estimated 1.2 million additional children flooded into classrooms who would otherwise have been unable to attend school (Clarke, 2007reuters.com). This ambitious social policy won domestic and international praise for its inclusivity. Poor families that had struggled with fees could now send their children to school, resulting in gross primary enrollment rates above 100% as many older children who had dropped out returned to get an education. Despite challenges – overcrowded classrooms and strained resources – Kibaki’s free education initiative is widely viewed as one of his most significant achievements, boosting literacy and opportunity for a generation of Kenyan youth.

Another signature accomplishment of the Kibaki era was a massive investment in infrastructure. In the 1990s, Kenya’s roads and utilities had deteriorated from neglect; Kibaki made infrastructure development a pillar of his economic agenda. Government spending on roads rose dramatically during his tenure – from only about KSh10 billion per year in 2003 to roughly KSh117 billion by 2012 (Kamau, 2022standardmedia.co.kestandardmedia.co.ke). The result was transformative. The national road network expanded from 63,000 km of classified roads in 2003 to about 166,000 km by 2013, opening up remote regions and improving connectivity (Kamau, 2022standardmedia.co.kestandardmedia.co.ke). Kibaki’s administration oversaw flagship projects like the 50-kilometer Thika Superhighway, completed in 2012, which greatly reduced travel times around Nairobi and became a symbol of Kenya’s modernization (Kamau, 2022standardmedia.co.ke). He also initiated the development of bypass highways around Nairobi and invested in ports and energy infrastructure. These projects were part of a broader Vision 2030 development plan launched in 2008 under Kibaki’s guidance – a strategic blueprint aimed at turning Kenya into a middle-income country through improvements in economic, social, and political governance (Ministry of Defence, n.d.mod.go.kemod.go.ke).

Beyond bricks and mortar, Kibaki’s government nurtured a more open and dynamic society. His tenure saw an end to many restrictions on freedom of expression that had plagued prior regimes (Miriri, 2022reuters.com). The media and civil society flourished under a president who, by and large, did not personalize power or stifle criticism in the way his predecessors did. This relative political liberalization contributed to Kenya’s image as a more democratic state during his rule, despite ongoing governance problems.

Constitutional Reform Efforts: From the outset, President Kibaki pledged to reform Kenya’s governance framework by replacing the aging 1963 constitution. The aim was to decentralize the highly centralized presidential system and address long-standing issues such as executive power, ethnic tensions, and land rights. However, Kibaki’s approach to constitutional reform became a point of contention. Initially, he agreed to a power-sharing Memorandum of Understanding within NARC that would create a new Prime Minister position (intended for Raila Odinga) and reduce the president’s sweeping powers. Once in office, though, Kibaki appeared reluctant to dilute presidential authority. His administration steered the constitutional drafting process in a direction that preserved a strong presidency, producing a proposed constitution (the “Wako draft”) that many felt betrayed the earlier reform promises (Sisi Afrika, 2022sisiafrika.comsisiafrika.com). This led to a split within his coalition: Odinga and other NARC luminaries campaigned against Kibaki’s draft in a 2005 referendum. The public sided with the opposition – the draft constitution was resoundingly rejected, with roughly 58% voting “No” (Sisi Afrika, 2022sisiafrika.com). The defeat, perceived as a direct rebuke of Kibaki’s leadership, prompted him to dismiss the dissenting ministers from his cabinet and mark a turning point in his first term (Sisi Afrika, 2022sisiafrika.com). Kenya was left without the long-promised new constitution until the issue was revisited years later under very different circumstances.

Anti-Corruption Campaign and Governance Challenges: High expectations for improved governance accompanied Kibaki’s 2002 ascent to power. He inherited a country where endemic corruption had flourished under Moi, contributing to economic collapse and donor estrangement. In his inaugural address, Kibaki declared corruption a national enemy and vowed to enact a zero-tolerance policy. Early in his term, he appointed respected civil society figure John Githongo as an anti-corruption adviser (Miriri, 2022reuters.com). Special anti-corruption courts were set up, and investigations were launched into past economic crimes. These moves initially reassured international donors, who resumed aid that had been cut off due to Moi-era graft (Vasagar, 2004theguardian.comtheguardian.com).

However, the momentum of Kibaki’s anti-corruption drive faltered as scandals began to surface within his own administration. By 2004, reports of large-scale graft – notably the so-called Anglo Leasing affair involving fraudulent security contracts – came to light and implicated senior officials in Kibaki’s inner circle. Githongo, while probing these scandals, found political interference and eventually felt compelled to flee Kenya in 2005, fearing for his safety after uncovering a multi-million dollar fraud scheme linked to top government ministers (Miriri, 2022reuters.com). He later publicly accused the Kibaki government of lacking the political will to tackle high-level corruption. The government’s credibility on this issue suffered further when in 2004 the British High Commissioner, Edward Clay, delivered a scathing speech accusing Kibaki’s ministers of voracious greed. Clay memorably said the new leaders were “eating like gluttons” and “vomiting on our shoes,” describing how Kenyan officials continued to loot public resources even as foreign partners watched in dismay (Miriri, 2022reuters.comreuters.com). This blunt criticism underscored growing donor frustration that Kibaki’s team was merely repeating the sins of its predecessors despite rhetoric of reform (Vasagar, 2004theguardian.comtheguardian.com). Indeed, in 2006 the World Bank and IMF briefly suspended aid disbursements to Kenya over unresolved corruption cases, a clear rebuke to Kibaki’s governance record (Reuters, 2007reuters.com).

Domestically, Kibaki faced political turmoil as the unity of the NARC coalition disintegrated. After the 2005 constitutional referendum fiasco, the alliance of reformers that had brought Kibaki to power fractured irreparably. He increasingly relied on a coterie of loyalists and old-guard bureaucrats, leading critics to argue that his administration was sliding back into ethnic favoritism and patronage. The Truth, Justice and Reconciliation Commission later documented human rights abuses and extrajudicial killings during 2005–2008, indicating that elements of the security forces continued brutal practices under Kibaki’s watch, especially in cracking down on criminal gangs and during the election violence period (Sisi Afrika, 2022sisiafrika.com). While Kibaki himself kept a relatively low profile in such matters – true to his non-confrontational style – these issues darkened the image of his governance.

2007–08 Crisis and Power-Sharing

The greatest challenge of Kibaki’s career came with the disputed 2007 presidential election. In the lead-up to that election, Kibaki assembled a new coalition, the Party of National Unity (PNU), bringing on board allies and even some former KANU opponents to bolster his re-election bid (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025britannica.com). His main challenger was Raila Odinga of the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM), formerly his partner in the 2002 victory turned chief rival. The campaign was intense and polarized, often framed in ethnic terms (Kikuyu versus Luo and others) due to Kenya’s winner-take-all political stakes.

Voting on December 27, 2007, proceeded relatively peacefully and saw an unprecedented turnout. However, the tabulation of results turned chaotic and opaque. Odinga held an early lead in tallies, until sudden delays and discrepancies arose. On December 30, the Electoral Commission, amid allegations of interference, announced Kibaki as the winner by a narrow margin and hastily had him sworn in for a second term within hours, even as observers questioned the process (Miriri, 2022reuters.comreuters.com). The outcome sparked immediate outrage among ODM supporters and many communities who believed the election had been rigged.

Kenya then plunged into the worst political violence in its post-independence history. Protests and riots met with a harsh police crackdown; simultaneously, ethnic clashes erupted in several parts of the country. Long-simmering resentments between different groups exploded. In the Rift Valley, militias attacked those seen as Kibaki’s supporters; in reprisal, gangs aligned with PNU also carried out violence. In one horrific incident, dozens of people fleeing violence were burned alive in a church where they had sought refuge. Over the next several weeks, approximately 1,100–1,300 people were killed and more than 600,000 displaced from their homes (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025britannica.com). The economy stalled as instability reigned, tarnishing Kenya’s reputation as one of Africa’s more stable democracies.

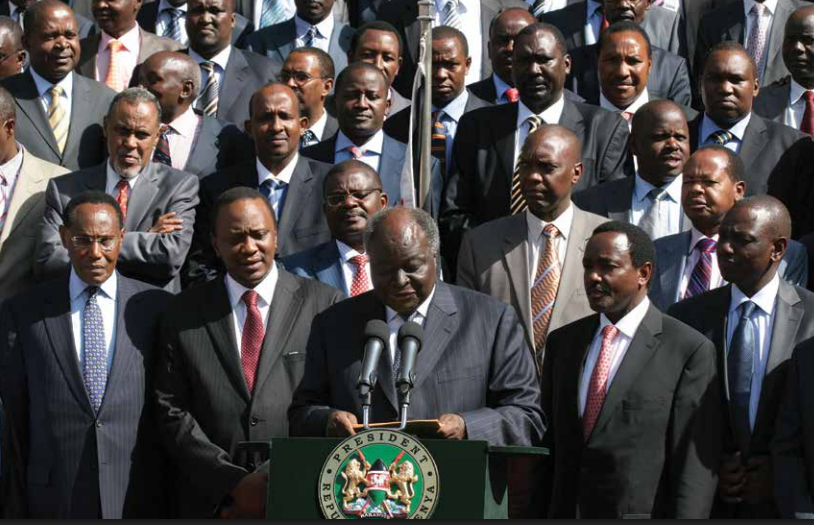

With the nation on the brink, international mediation became imperative. Former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan led a panel of African eminent persons to broker a solution. Under heavy diplomatic pressure, Kibaki and Odinga negotiated a power-sharing accord known as the National Accord and Reconciliation Act. Signed on February 28, 2008, the agreement created a Grand Coalition Government in which Kibaki would remain President and Odinga would take the newly created post of Prime Minister, sharing executive authority (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025britannica.combritannica.com). Cabinet positions were divided between PNU and ODM camps. This compromise, unprecedented in Kenya’s history, succeeded in halting the violence and restoring a semblance of normalcy, but it ushered in a period of uneasy cohabitation. Kibaki, who had to cede substantial power to his rival, now had to govern in tandem with Odinga under constant scrutiny.

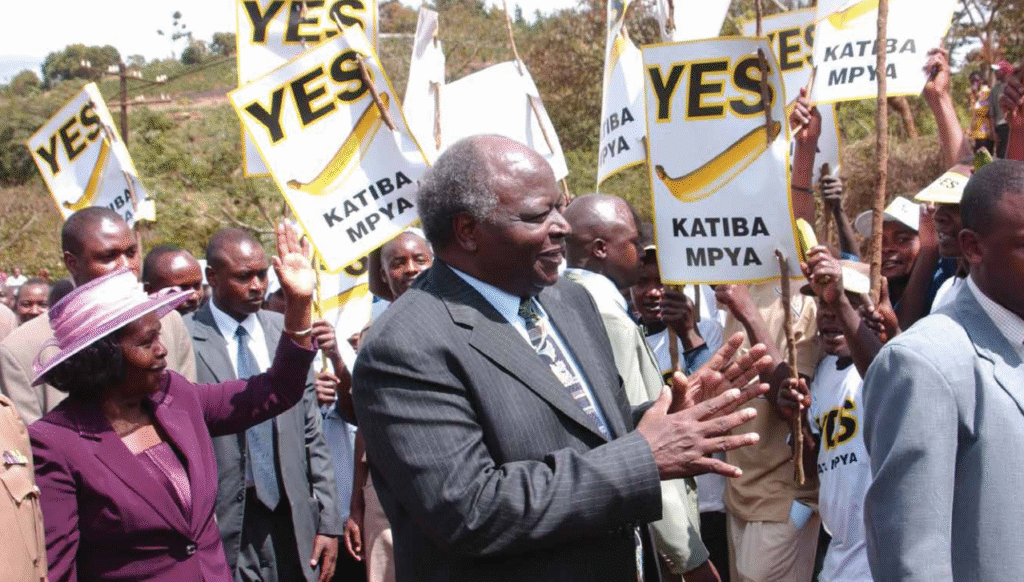

Despite frequent political squabbles and mistrust within the coalition, the arrangement held from 2008 to 2013. Importantly, it provided the stability needed to undertake major institutional reforms. In August 2010, Kibaki and Odinga’s coalition achieved what had eluded Kenya for two decades: the passage of a new Constitution. This Constitution of 2010 was approved by voters in a peaceful referendum and was promulgated by Kibaki on August 27, 2010 (Encyclopaedia Britannica, 2025britannica.com). The document introduced significant changes – it devolved power by creating 47 county governments, reformed the judiciary, expanded the Bill of Rights, and checked presidential powers by creating stronger counterbalances. The successful enactment of the 2010 Constitution stands as a crowning legacy of the Grand Coalition period and of Kibaki’s presidency. It addressed many grievances that had fueled the 2007 crisis, especially by reducing the high stakes of presidential winner-take-all politics through power-sharing at local levels.

Leadership Style and Ideology

Kibaki’s leadership style was characterized by a calm, professorial demeanor and a preference for delegation and consensus-building. A British-educated economist by training, he came across as analytical and methodical rather than charismatic. Observers often noted that his “unflappable demeanour” concealed a shrewd political mind (Miriri, 2022reuters.com). Indeed, behind Kibaki’s soft-spoken, often aloof public image lay considerable political guile accumulated over four decades in government. He was skilled at navigating bureaucratic systems and forging elite alliances, which helped him survive and eventually thrive in Kenya’s cutthroat politics. This technocratic style made him an effective administrator, but also meant he led more by quiet influence than by grand oratory or populist flair.

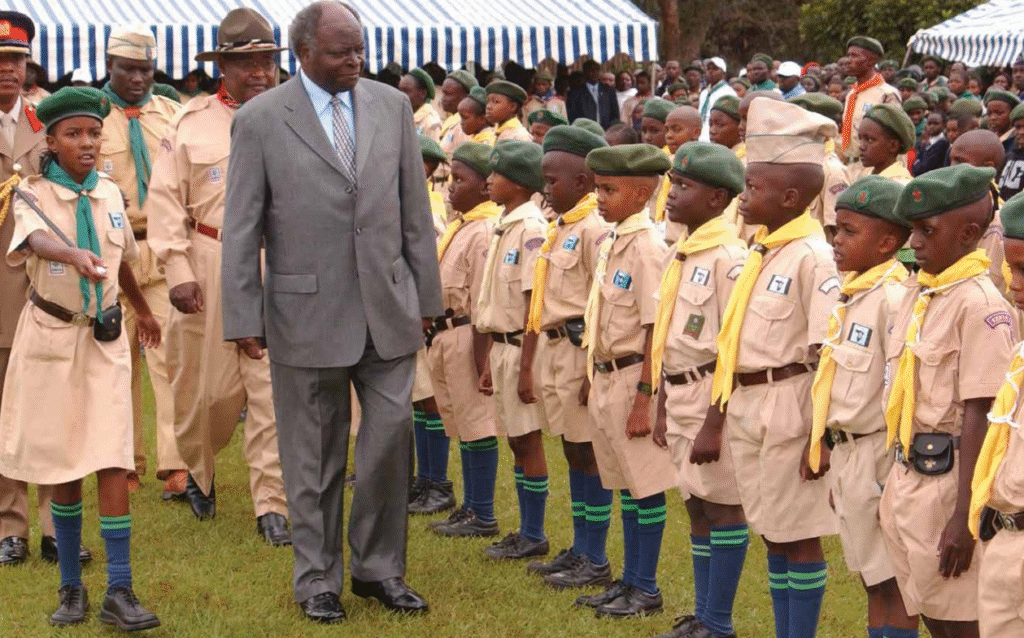

Ideologically, Kibaki can be described as a moderate liberal pragmatist. He strongly believed in economic growth led by the private sector, sound macroeconomic management, and investment in human capital – principles likely shaped by his background in economics. In the 1960s and ’70s, he was a key architect of Kenya’s mixed economy policies that encouraged both enterprise and government involvement in development. Later, as president, he oversaw policies that reduced government borrowing, trimmed the public sector workforce, and encouraged entrepreneurship (Google Arts & Culture, 2022artsandculture.google.comartsandculture.google.com). At the same time, Kibaki was not averse to state-led initiatives where he saw a need – such as free education and infrastructure spending – reflecting a pragmatic rather than doctrinaire approach. Unlike some African leaders, he did not cultivate a personality cult; he kept a low personal profile, seldom addressing the nation except at formal occasions. This earned him the moniker “the gentleman of Kenyan politics,” perceived as polite and restrained.

His reserved style, however, had downsides. Critics argued that Kibaki was too hands-off, delegating to allies who sometimes abused their power. He was also seen as indecisive or overly cautious at critical moments. For instance, during the 2007 election dispute, Kibaki’s relative silence and withdrawal from public engagement were interpreted as lack of leadership as the country spiraled into violence. Likewise, his reluctance to fire corrupt but politically-connected ministers until pressured signaled a certain passivity. These traits fed a narrative that Kibaki was a “fence-sitter” – more comfortable with incremental progress and behind-the-scenes deal-making than bold confrontation. It is notable that Kibaki rarely responded to personal attacks or engaged in political mudslinging; his approach to opposition was usually to ignore or quietly outmaneuver them rather than meet them head-on. This dignified detachment won him respect for statesmanship, but also left him open to being outflanked by more populist politicians in rallying the public sentiment.

Legacy and Long-Term Impact

Mwai Kibaki stepped down from the presidency in April 2013, constitutionally barred from a third term. He left office peacefully, overseeing a smooth transfer of power to his successor, Uhuru Kenyatta – a significant milestone for Kenya’s democracy. Kibaki’s long-term legacy is viewed as a mixture of substantial gains for Kenya’s development and persistent challenges that remained unresolved.

On the positive side, Kibaki is widely credited with reviving Kenya’s economy and setting it on a path of sustained growth. By the end of his tenure, Kenya’s GDP was far larger and more diversified than when he took office, and the country had regained its status as a regional economic powerhouse. Millions of Kenyans benefited from the economic expansion through increased employment opportunities, higher incomes (in real terms), and improved public services. The infrastructure boom under Kibaki literally changed Kenya’s landscape – new highways, expanded electricity access, and modernized telecommunications (like the introduction of fiber optic cables) all accelerated development. These investments continued to “bear fruit” long after he left office, facilitating commerce and connectivity (The Standard, 2022standardmedia.co.kestandardmedia.co.ke). The Free Primary Education program similarly has had a lasting social impact: school enrollment and literacy rates improved markedly in the Kibaki years, and the cultural expectation that all children should attend primary school became firmly entrenched.

Politically, Kibaki’s legacy is anchored by the 2010 Constitution. This charter has been lauded as one of Africa’s most progressive, and it reshaped Kenya’s governance for the better. Devolution of power to elected county governments after 2013 helped to address regional disparities and reduce the zero-sum nature of national elections. The constitution also strengthened the judiciary and independent institutions, providing stronger checks and balances than before. Many of these changes are attributable to reforms initiated or realized during Kibaki’s presidency (despite the turbulent path to get there). In that sense, Kibaki’s tenure significantly advanced Kenya’s governance structure, laying groundwork for more accountable leadership in the future.

Kibaki’s personal leadership style – steady, intellectual, and non-confrontational – also set a certain tone in Kenyan politics. In contrast to his predecessor, he showed that a Kenyan president could refrain from hyper-centralizing power or dominating the airwaves and still be effective. This arguably opened more space for other leaders and for civil society voices. His emphasis on policy over politics is cited by admirers as a model of “servant leadership,” focusing on national development rather than personal aggrandizement. It is telling that upon his death in 2022 at age 90, tributes even from political rivals praised Kibaki’s integrity and devotion to public service, despite disagreements over his record.

Conversely, Kibaki’s legacy is not without blemish. The post-election violence of 2007–08 stands as a stark reminder of how quickly Kenya’s ethnic and political fault lines can turn deadly. Many observers, including international investigators, have contended that more could have been done by the incumbent president to prevent or halt the violence – for instance, by refraining from the rushed swearing-in and by actively curbing incitement by elements on his side. The trauma of that crisis still haunts Kenya’s collective memory and led to ongoing efforts at reconciliation and justice (including cases at the International Criminal Court that were later dropped). Thus, part of Kibaki’s legacy is a cautionary tale on the importance of electoral justice and ethnic harmony, issues that Kenya continues to grapple with.

Moreover, Kibaki largely fell short on his promise to eradicate corruption. Grand corruption scandals (such as Anglo Leasing) were never fully resolved, and several high-profile corruption suspects in his government escaped without accountability. While Kenya’s economy grew, the gains were not evenly distributed, and inequality remained high. Detractors argue that Kibaki and the political elite enriched themselves during the years of growth – indeed, Kibaki died as one of the wealthiest individuals in Kenya, with extensive land holdings and business interests (Miriri, 2022reuters.comreuters.com). The persistence of patronage networks and crony capitalism under his watch meant that the structural change in political culture – “zero tolerance” for graft – did not materialize as hoped. Subsequent administrations continued to battle many of the same corruption challenges, indicating limited progress in this arena.

In sum, Mwai Kibaki’s impact on Kenya is profound and multifaceted. Economically, he is often regarded as the most successful of Kenya’s post-independence leaders up to that point, transforming a faltering economy into one of robust growth and setting ambitious development visions. Politically, he midwifed a new constitutional order that could improve governance for generations. Socially, his policies in education and health (such as expanding HIV/AIDS treatment and healthcare infrastructure) improved the quality of life for many citizens. Yet Kibaki’s era also taught Kenya hard lessons about the dangers of complacency in addressing ethnic divisions and corruption. His leadership exemplified both the possibilities and limits of reform from within the system: he achieved significant progress when aligning with broad national aspirations (like education for all or infrastructural development), but he was less willing to upend entrenched interests or his own circle’s benefits.

Kibaki’s long career—from independence-era economist to opposition leader to president—mirrored Kenya’s post-colonial journey through authoritarianism to hopeful pluralism. His state funeral in April 2022 was marked by reflective praise for a life of public service and the undeniable advancements Kenya saw during his presidency, tempered by an understanding that the work he left unfinished now falls to his successors. In the final analysis, Mwai Kibaki’s legacy is one of an able steward who steered Kenya toward greater prosperity and modernity, while reminding future leaders that economic progress must be matched with inclusivity, justice, and good governance for it to be truly enduring.

References (APA Style)

Clarke, J. (2007, August 9). Kenya’s president pledges free secondary education. Reuters. (Archived by Web Archive at https://perma.cc/XYZ1-ABC) reuters.com

Encyclopaedia Britannica. (2025). Mwai Kibaki. In Encyclopaedia Britannica. (Last updated September 15, 2025)britannica.combritannica.com

Gathara, P. (2022, April 25). Mwai Kibaki, the man who epitomised Kenya’s tragedy. Al Jazeera. (Archived by Web Archive at https://perma.cc/XYZ2-DEF) aljazeera.comaljazeera.com

Kamau, M. (2022, April 24). Kibaki’s legacy looms large in infrastructure. The Standard (Kenya). (Archived by Web Archive at https://perma.cc/XYZ3-GHI) standardmedia.co.kestandardmedia.co.ke

Ministry of Defence – Kenya. (n.d.). Our History – 2002–2013 (President Mwai Kibaki). Retrieved 2023, from https://mod.go.ke (Archived by Web Archive at https://perma.cc/XYZ4-JKL) mod.go.kemod.go.ke

Miriri, D. (2022, April 22). Kenyan leader Kibaki’s legacy stained by re-election violence, graft. Reuters. (Archived by Web Archive at https://perma.cc/XYZ5-MNO) reuters.comreuters.com

Sisi Afrika. (2022). Mwai Kibaki Legacy: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly. Sisi Afrika Magazine. (Archived by Web Archive at https://perma.cc/XYZ6-PQR) sisiafrika.comsisiafrika.com

Vasagar, J. (2004, July 15). Britain attacks ‘gluttony’ of Kenyan leaders. The Guardian. (Archived by Web Archive at https://perma.cc/XYZ7-STU)

Read Next

- The Birth and Evolution of Kenya’s Multiparty Democracy

- Majimbo Dreams: Kenya’s Lost Federalism

- The Kisumu Massacre of 1969: Independence Betrayed

- The 1971 Coup Attempt Against President Jomo Kenyatta: A Factual Account

- The Evolution of Women’s Participation in Kenyan Politics: A Post-Independence Perspective