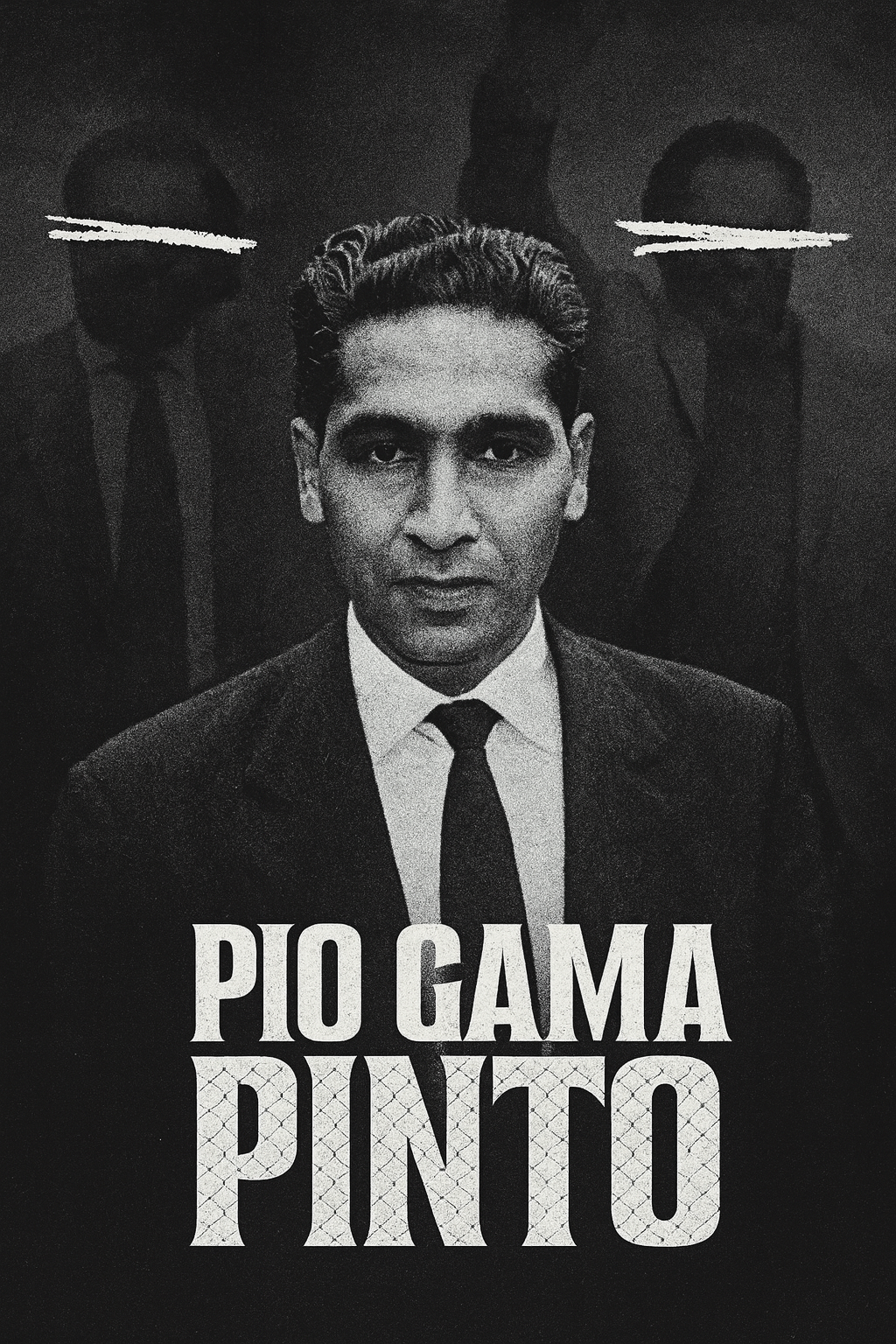

On the morning of February 24, 1965, Nairobi woke to a silence that would last decades. A car rolled out of the driveway of a modest home in Westlands. Inside sat Pio Gama Pinto, journalist, activist, socialist, and one of the most dangerous men to Kenya’s new ruling class. Moments later, three shots rang out. Pinto slumped dead beside his daughter. He was 38.

Pinto’s death marked more than the end of a man’s life. It symbolized the assassination of Kenya’s socialist dream — the brief flicker of a different path after independence, one that promised equality instead of privilege, redistribution instead of patronage. For a country barely two years old, the bullets that killed Pinto announced a new era of silence and fear.

Between Empires

Born in Nairobi in 1927, Pinto was of Goan descent, a community caught between colonial categories — not white enough to rule, not African enough to belong. He studied in India during its independence struggle and joined student movements fighting Portuguese colonial rule in Goa. Those years shaped him: he returned to Kenya not as a privileged Goan but as an anti-imperialist convinced that freedom without justice was meaningless.

He joined the East African Indian Congress, Kenya African Union, and local trade unions, becoming a rare link between Indians and Africans in the struggle for liberation. Pinto’s loyalty lay squarely with Africans fighting for land and dignity. When the Land and Freedom Army (Mau Mau) took up arms, he helped from the shadows — raising funds, sending supplies, and caring for families of detainees. British intelligence reports identified him as one of the “key civilian coordinators” of the rebellion’s urban network.

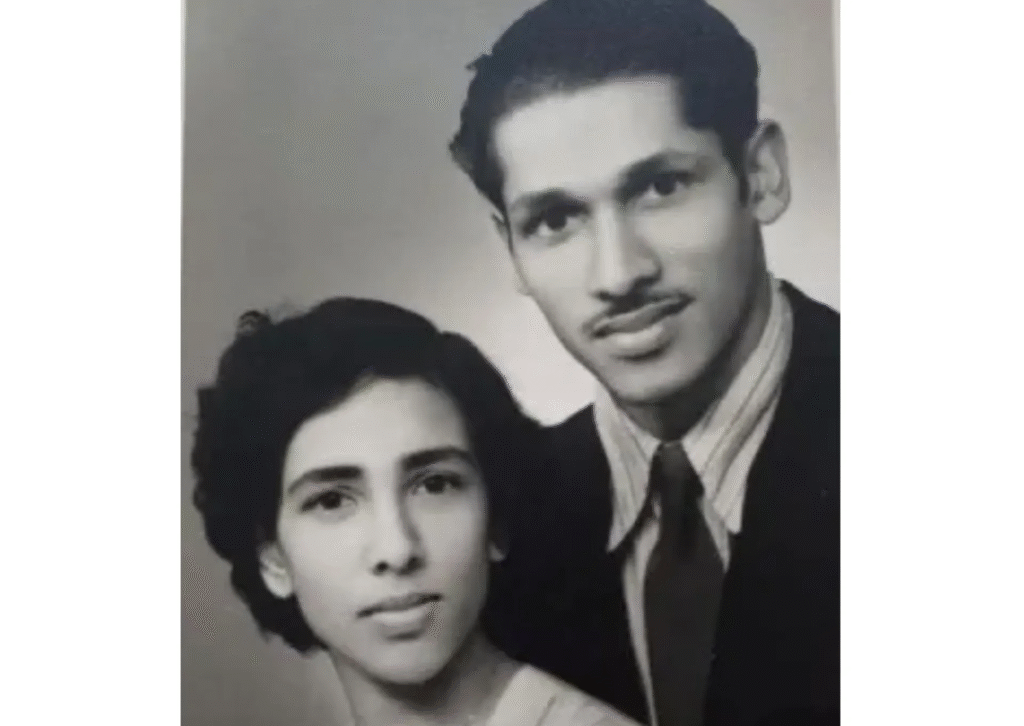

His reward was detention in 1954, just five months after he married Emma. He spent nearly five years behind barbed wire. When his father died during that time, colonial authorities denied him permission to attend the funeral. Pinto’s personal sacrifice would become the hallmark of his politics: a relentless belief that liberation required moral courage more than comfort.

Propaganda and the Politics of Liberation

After his release in 1959, Pinto re-entered a Kenya that was slowly negotiating independence. He turned to what he knew best — information. He helped establish the Pan-African Press, publishing radical periodicals such as Sauti ya Afrika, Pan Africa, and Nyanza Times. These papers connected African liberation movements and criticized neo-colonial dependency.

Pinto’s journalism was political warfare. He believed that freedom would be lost not by colonial repression but by the complacency of new African elites. His writings argued that independence should not reproduce the same racial and economic hierarchies left by the British. That message earned him friends among left-leaning activists — and enemies among those who preferred the comfort of compromise.

He became a close adviser to Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, then Kenya’s vice president and the leading voice for socialism. Pinto’s modest house in Westlands became a meeting point for African liberation figures, trade unionists, and embassy officials from the Eastern Bloc. As Shiraz Durrani notes, Pinto saw socialism not as imported ideology but as the logical extension of African communalism — “the moral economy that colonialism had destroyed.”

Building the Socialist Dream

In 1964, Kenya’s new elite was already drifting from its revolutionary promises. Tom Mboya’s Sessional Paper No. 10 on African Socialism laid out an economic policy that mixed free-market growth with selective welfare. Pinto, Odinga, and their allies saw it as betrayal — a capitalist document wearing socialist clothing.

Pinto quietly drafted an alternative blueprint demanding a cap on land ownership, redistribution of wealth, and compensation for Mau Mau veterans. It was an audacious challenge. In a young state dependent on Western aid, Pinto’s defiance amounted to heresy.

He founded the Lumumba Institute, a training center for KANU cadres named after the assassinated Congolese leader Patrice Lumumba. Its mission was to create a generation of ideological leaders immune to corruption. To Western diplomats, it looked like a communist nursery. To Kenyan conservatives, it was the embryo of a coup.

By 1964, the CIA and MI6 had classified Pinto as “a leftist firebrand to be watched closely.” His linkages with Chinese, Soviet, and Indian contacts made him the most internationally connected of Kenya’s leftists. Yet his demeanor was disarmingly humble. Friends remembered him cycling to meetings, skipping meals, and working late into the night — “decent, fearless, and honest,” in the words of Zahid Rajan.

Enemies Within

The struggle within KANU soon became a cold war of its own. On one side stood Kenyatta, Mboya, and the emergent capitalist class — mostly Western-educated men eager to build a strong central state tied to private enterprise. On the other stood Odinga, Pinto, Bildad Kaggia, and others demanding redistribution, state planning, and moral governance.

Pinto became the bridge between radicals and the state, a position that was both strategic and suicidal. In Parliament, he argued that independence meant nothing if land and wealth remained in the hands of a few. His speeches criticized corruption and patronage at a time when these were becoming the new currencies of power.

Behind the scenes, he supported trade unions and student movements, including the Kenya African Workers’ Congress, which rejected Western-controlled labor federations. He also kept communication with liberation fronts across Africa, providing logistical and moral support to anti-colonial fighters in Mozambique and Angola.

For Kenya’s new rulers, this was dangerous. The state was barely stable; the last thing it needed was a man capable of uniting workers, students, and leftist politicians under one ideology.

The Assassination

On that February morning in 1965, Pinto walked out of his home, his young daughter beside him. He was heading to work when a man approached the car and fired three times. Pinto died instantly.

The investigation that followed was a theatre of obfuscation. Kisilu Mutua, a low-ranking house employee, was arrested and convicted for the murder, but his supposed accomplices were never found. Mutua served more than 35 years before being released, maintaining his innocence to the end. To many, he was the convenient scapegoat for a political crime.

Durrani notes that no high-level inquiry was ever pursued. The case files vanished into bureaucratic fog. Within weeks, Odinga found himself increasingly isolated, and within a year he would resign as vice president. Kenya’s ideological rift was sealed — capitalism had won, and socialism was buried with Pinto.

After the Silence

In the decades that followed, Pinto’s name faded from textbooks. His widow, Emma Pinto, quietly petitioned for recognition, even as the state avoided any public memorial. When younger activists rediscovered him in the 1970s and 1980s, it was as a ghost — the moral ancestor of those who dared question the regime.

For Kenya’s political establishment, forgetting Pinto was convenient. His memory questioned the legitimacy of the post-independence project. He had argued that the struggle for freedom was not over in 1963; it merely changed masters.

Yet his vision survives in fragments — in student unions, radical presses, and the occasional speech about justice that still invokes uhuru na usawa (freedom and equality). Pinto’s story remains a warning that revolutions can be betrayed not by enemies but by their own children.

Legacy of a Martyr

To call Pio Gama Pinto an unsung hero is to underestimate his influence. He was Kenya’s first political martyr, killed not by colonizers but by the system he helped create. He represented a possibility — a multi-racial, socialist Kenya that could have existed before Cold War realpolitik and elite greed strangled it.

His life bridged continents and classes: a Goan Catholic who stood with Kikuyu guerrillas; a parliamentarian who preferred underground meetings to pomp; a man who chose justice over comfort. Pinto’s death closed a chapter of moral clarity in Kenya’s history.

Today, the road near his old home in Westlands still bears his name, but few stop to remember what it means. Behind that sign lies a story of sacrifice, conviction, and betrayal — the story of a man who dreamed that independence would mean equality, and paid for it with his life.

References

- Durrani, S. (2018). Pio Gama Pinto: Kenya’s Unsung Martyr (1927–1965). Vita Books.

- Rajan, Z. (2009). “Pio Gama Pinto (1927–1965).” In The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest, ed. Immanuel Ness. Wiley-Blackwell.