Raila Amolo Odinga (born 1945) stands as one of Kenya’s most consequential and enduring politicians. Over a career spanning four decades, Odinga has been at the center of Kenya’s struggle for democracy, constitutional reform, and opposition politics. He is often called “Baba” (father) by his supporters, revered as a champion of the people, and nicknamed “Agwambo” (the mysterious or unpredictable one) for his political maneuvers (Reuters, 2025). This article traces Raila Odinga’s biography from his early life through his leadership in the pro-democracy movement, the formation of political parties, major election battles in 2007, 2013, 2017, and 2022, shifting alliances with former rivals, and his role in reforms such as the landmark 2010 constitution. It also examines his legacy, controversies, and ongoing impact on Kenyan political identity. Throughout, Odinga’s story is interwoven with the broader narrative of Kenya’s post-independence politics – from ethnic nationalism and the quest for “second liberation” to the challenges of opposition in a developing African democracy.

Early Life and Political Origins

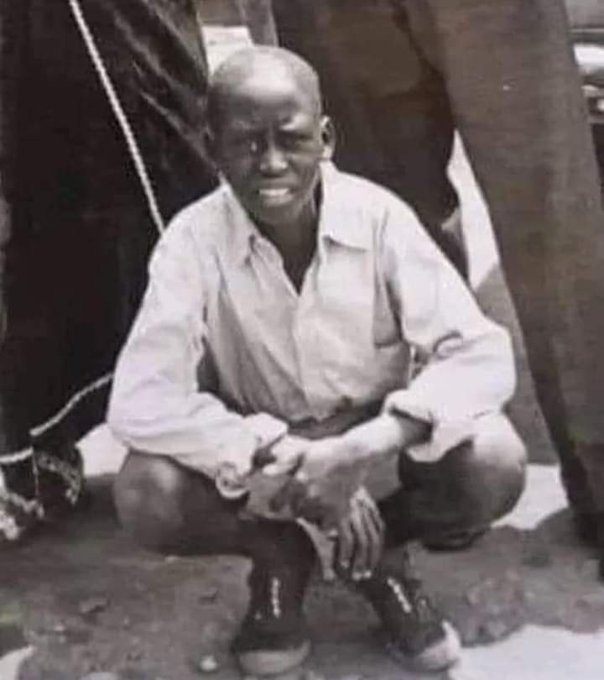

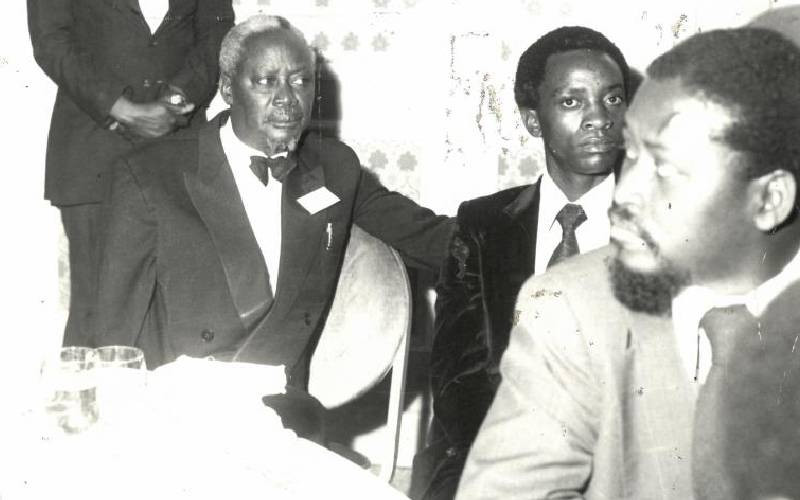

Born on January 7, 1945 in Maseno, western Kenya, Raila Odinga was the son of Jaramogi Oginga Odinga – a prominent independence leader who became Kenya’s first Vice President (Muthomi, 2025). Oginga Odinga was a close ally-turned-critic of President Jomo Kenyatta, and their 1960s falling-out along ideological and ethnic lines set the stage for enduring political cleavages in Kenya (Opondo, 2014). The elder Odinga championed a socialist, inclusive vision and was conceptualized as the symbolic leader of the Luo community and the “doyen” of opposition politics, while Kenyatta centralized power among his Kikuyu allies (Opondo, 2014). This early dichotomy between the Odinga and Kenyatta families – Luo versus Kikuyu, opposition versus establishment – would later re-emerge in Kenya’s multi-party era, including in the rivalry of their sons, Raila Odinga and Uhuru Kenyatta.

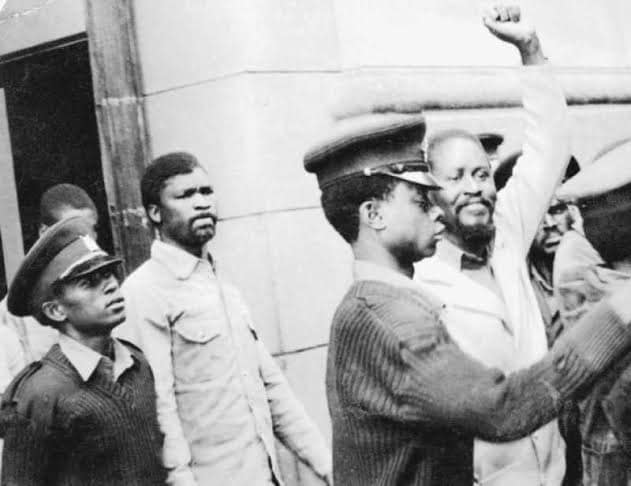

Raila Odinga’s upbringing and education prepared him for public life. He studied in East Germany at the Technical University of Magdeburg, graduating in 1970 with a degree in mechanical engineering. He returned to Kenya and became a lecturer, then a businessman, founding the East African Spectre Ltd., a manufacturing firm (Badejo, 2006). Odinga’s entry into politics occurred under the authoritarian one-party regime of President Daniel arap Moi. Inspired by his father’s opposition stance and disturbed by state repression, he became involved with underground pro-democracy networks in the late 1970s and early 1980s. In 1982, elements of the air force attempted a coup against Moi. Although Odinga’s exact role remains contested, the Moi government accused him of complicity in the failed putsch, leading to his arrest and detention (Reuters, 2025). Odinga would later downplay involvement in the coup, but the incident marked him as a notable dissident. He was imprisoned without trial in 1982 and spent an estimated six to nine years in detention (much of it in solitary confinement) through the 1980s for his political activities (Reuters, 2025). As Odinga later reflected, “Detention is a good school. You learn to reflect and think… You also learn tolerance, to be forgiving, particularly against your adversaries” (quoted in Reuters, 2025). These years of incarceration hardened Odinga’s reputation as a resilient advocate for political change during a time when Kenya’s autocratic state routinely jailed, tortured or exiled critics.

The Fight for Multi-Party Democracy

Odinga emerged from detention in the late 1980s into a Kenya still under Moi’s one-party rule but with growing calls for change. Internally, clergy, civil society, and opposition figures pressed for pluralism, while externally the end of the Cold War brought new pressure on African autocrats to reform (Kenyan History Team, 2025). Raila Odinga became a key figure in Kenya’s “Second Liberation” – the pro-democracy movement of the late 1980s and early 1990s that sought to end KANU’s monopoly on power. In July 1990, protests like the Saba Saba demonstrations rocked Nairobi, and in 1991 Moi finally agreed to repeal the one-party clause (Section 2A) of the constitution, re-legalizing opposition parties (Kenyan History Team, 2025). Odinga, alongside other opposition luminaries such as Kenneth Matiba, Charles Rubia, and his father Oginga Odinga, led mass rallies and risked re-arrest to demand political pluralism. He was detained again briefly in 1990, and then fled into temporary exile in 1991, highlighting the perils faced by agitators (Muthomi, 2025). By the close of 1991, multiparty democracy was restored – a reform that Odinga and others had paid a high personal price to achieve. This achievement of 1991 would later be seen as one of Odinga’s most important contributions to Kenyan democracy (Reuters, 2025).

In Kenya’s first multiparty elections of 1992, Raila Odinga was elected Member of Parliament for Langata constituency in Nairobi (Reuters, 2025). He represented the Forum for the Restoration of Democracy–Kenya (FORD-Kenya) party initially led by his father. After Oginga Odinga’s death in 1994, Raila was embroiled in a leadership tussle within FORD-Kenya. When he lost the party presidency to Kijana Wamalwa, the ambitious Odinga left to form his own party, the National Development Party (NDP) in 1994 (Badejo, 2006). This moment was an early indication of Odinga’s political independence and willingness to break alliances – a recurring feature of his career. Throughout the 1990s, Odinga built NDP into a regional force in his native Luo Nyanza and a personal political vehicle. In the 1997 general election, he ran for president under NDP, finishing third with about 10% of the vote (behind Moi and runner-up Mwai Kibaki) (Muthomi, 2025). Although he did not win, Odinga’s growing base of support signaled that he was more than a regional player. By the late 1990s, he had also earned a reputation as a firebrand who gave voice to frustrated youth and marginalized communities. He styled himself a left-leaning reformer; for instance, he named his first son Fidel Castro Odinga in honor of the Cuban revolutionary, underscoring his anti-imperialist and socialist sympathies (Reuters, 2025).

Party Formation and Shifting Alliances

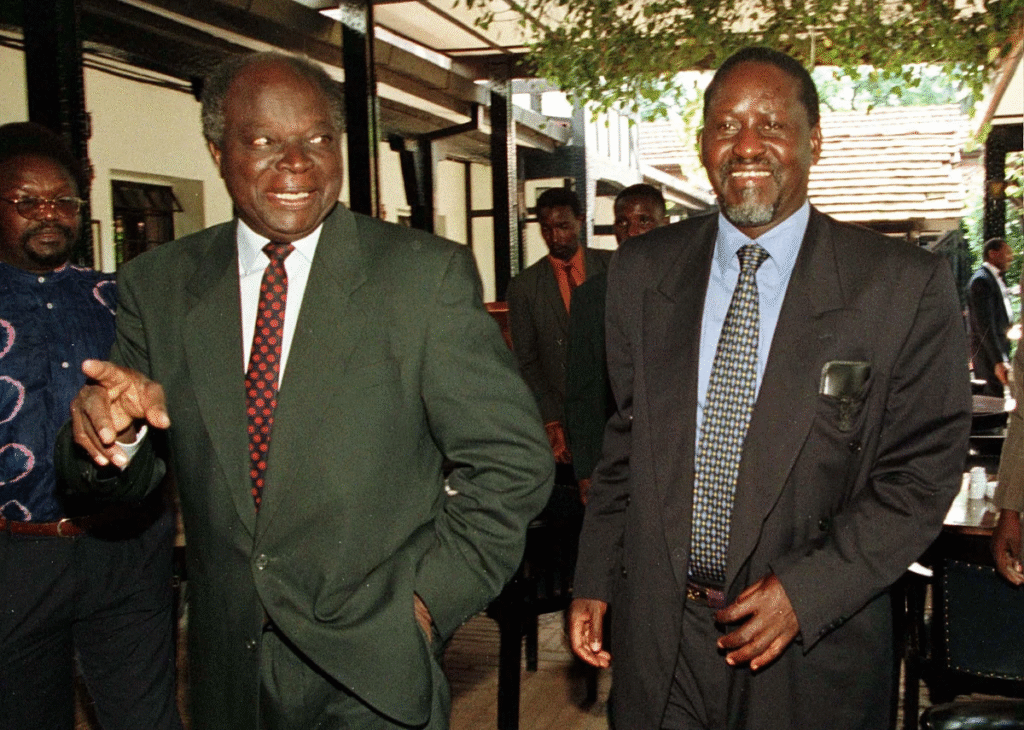

A hallmark of Raila Odinga’s political journey has been his fluid approach to alliances – partnering with yesterday’s enemies and, when expedient, discarding friends. In 2001, Odinga shocked many by making a pragmatic truce with President Moi, the same ruler who had detained him. Odinga agreed to have NDP merge into Moi’s ruling KANU party, in what became known as the “New KANU” experiment (Muthomi, 2025). He was brought into the government as Minister for Energy in 2001. Analysts viewed this move with skepticism; some saw it as opportunistic and motivated by Odinga’s search for an inside track to the presidency (Wapukha, 2025). Indeed, Odinga himself said of democratization that “it is a process” rather than something achieved overnight, reflecting his willingness to play the long game (Reuters, 2025). The alliance with Moi was short-lived. In 2002, President Moi attempted to anoint Uhuru Kenyatta (Jomo Kenyatta’s son) as his successor, passing over Odinga and other hopefuls within KANU. Feeling betrayed, Odinga famously rallied a group of KANU insiders to revolt, declaring “Kibaki Tosha!” (“Kibaki is enough”) to endorse opposition leader Mwai Kibaki’s presidential candidacy (Kenyan History Team, 2025). Odinga and others broke away to form the Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) and joined the broad opposition coalition named the National Rainbow Coalition (NARC) ahead of the 2002 elections.

The 2002 election was a watershed: the united opposition defeated Moi’s heir Uhuru Kenyatta, ending KANU’s 39-year rule. Raila Odinga’s backing of Kibaki was seen as crucial to NARC’s success and to the first peaceful transfer of power in independent Kenya’s history (Muthomi, 2025). In return, Odinga expected Kibaki to honor a pre-election Memorandum of Understanding that promised power-sharing, including a new prime minister post and a new constitution to curb the presidency. Kibaki, however, reneged on creating the PM position and stacked his government with his own allies, sidelining Odinga’s LDP faction. This led to a rift that would reshape Kenyan politics. By 2005, Odinga had once again moved into opposition, spearheading the campaign against Kibaki’s draft constitution in a national referendum. Odinga led the “No” camp under the banner of the Orange – a symbol that evolved into the Orange Democratic Movement (ODM) party (Muthomi, 2025). The 2005 referendum was resoundingly won by Odinga’s side (the “Orange” team), marking Kibaki’s proposed constitution as rejected by voters. Kibaki then dismissed Odinga and other LDP ministers from the cabinet. This confrontation firmly established Odinga as Kibaki’s chief opponent heading into the next election.

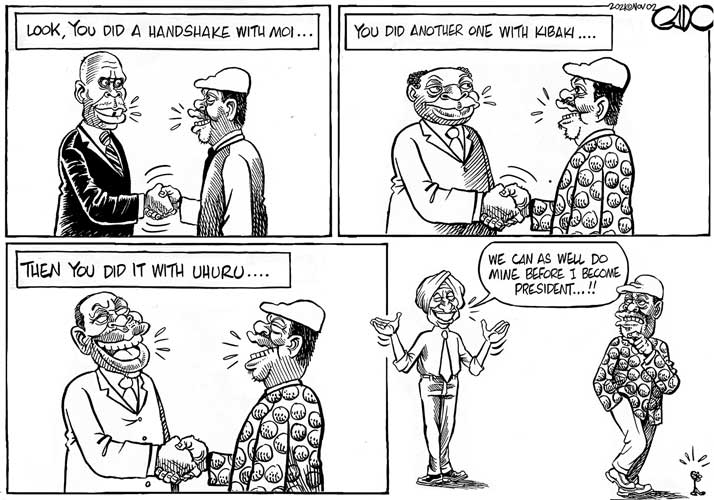

Odinga’s ability to reconcile with rivals yet again was demonstrated in subsequent years. In his career he has joined forces with three different presidents he once opposed – Moi, Kibaki, and later Uhuru Kenyatta – illustrating a political flexibility that has earned both praise and criticism. His nickname “Agwambo” or “mysterious one” speaks to this chameleon-like skill of alliance-building (Reuters, 2025). As one analysis put it, “Nobody can claim to have the Midas touch in the politics of Kenya more than Raila Odinga… his ‘situational management style’ allows him to make up with erstwhile enemies just as he discards groupings when needed” (Wandati, 2019). Odinga’s shifting alliances often reflected calculations to achieve long-term goals like constitutional reform or electoral victory, even at the cost of short-term reputational damage.

The 2007 Election and Post-Election Crisis

By 2007, Raila Odinga had transformed ODM into a national party and was the opposition’s presidential candidate challenging the incumbent, Mwai Kibaki. The campaign was intense and ethnically polarized, with Odinga positioning himself as the candidate of change under the slogan “Real Change” and advocating devolution (“ugatuzi”) of power and resources to regions (Kenyan History Team, 2025; Wapukha, 2025). Kibaki’s camp, by contrast, cast devolution as a dangerous revival of “majimbo” (federalism) that could sow ethnic division – a sensitive topic harking back to past ethnic clashes (Kenyan History Team, 2025). The election, held in December 2007, became one of the most fiercely contested and controversial in Kenya’s history. When the Electoral Commission hurriedly declared Kibaki the winner amid allegations of vote rigging, Kenya descended into chaos. Protests and ethnic violence erupted, especially in the Rift Valley and slum areas like Kibera in Nairobi. Over 1,100 people were killed and hundreds of thousands displaced in weeks of clashes pitting mainly Odinga’s supporters (largely Luo, Luhya, and Kalenjin communities) against those perceived to back Kibaki (largely Kikuyu) (Reuters, 2025; Muthomi, 2025). The 2007–08 post-election violence was the worst crisis in Kenya since independence.

Despite his deep grievance at the stolen election, Odinga played a critical role in resolving the crisis. Under international pressure and mediation led by former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan, Kibaki and Odinga negotiated a peace settlement. Odinga agreed to a power-sharing deal – the National Accord – that created a coalition government in April 2008 with Kibaki as President and Raila Odinga in the newly-recreated post of Prime Minister (Muthomi, 2025). This “Grand Coalition” government (referred to colloquially as nusu mkate, or “half a loaf”) was unprecedented in Kenya. Odinga’s decision to join the government was met with mixed reactions. Many of his followers accepted it as a necessary compromise to end bloodshed and address long-standing injustices, noting that his involvement helped initiate important reforms (Wapukha, 2025). Indeed, Odinga used his premiership to push for a new constitution and institutional changes agreed upon in the peace accord. Critics, however, argued that the deal exemplified an elite pact that left underlying issues of injustice unresolved; they point out that power-sharing cooled tensions but also co-opted opposition leaders into the establishment, thereby diluting accountability (Wapukha, 2025). Nonetheless, Odinga’s tenure as Prime Minister (2008–2013) was historic: it made him the second person to hold that office since Jomo Kenyatta (who was PM at independence), and it underscored his stature as more than just a perennial opposition figure but a statesman capable of governance.

Champion of Reform and the 2010 Constitution

One of Raila Odinga’s most significant contributions to Kenya was his advocacy for constitutional reform, culminating in the 2010 Constitution. The need for a new constitution had been a rallying cry since the 1990s, and was part of the unmet promises of 2002 that had caused Odinga’s split with Kibaki. After the 2007 turmoil, constitutional change became urgent to address systemic problems – concentration of power, lack of checks and balances, and regional and ethnic grievances over resource allocation. Odinga was a leading champion of the constitutional review process between 2008 and 2010, working alongside President Kibaki in the coalition government to shepherd reforms (Wapukha, 2025). The result was a proposed new constitution that, among other things, expanded the Bill of Rights, devolved significant powers and funding to 47 new county governments, and reformed the judiciary and electoral commission. During the 2010 referendum campaign, Odinga energetically campaigned for the draft constitution, emphasizing that it would entrench multi-party democracy, decentralize power (devolution), and prevent a repeat of past injustices (Wapukha, 2025). The new constitution was overwhelmingly approved by voters in August 2010, a landmark in Kenya’s political evolution.

The 2010 Constitution is often considered the crowning policy achievement of Raila Odinga’s career. It answered, at least in structure, the long-standing opposition demands for “ugatuzi” (devolution of resources and authority) that Odinga and others had fought for. Analysts note that Odinga’s legacy as a reformist is tied to “two of Kenya’s most important reforms: multiparty democracy in 1991 and a new constitution in 2010” (Reuters, 2025). The constitution introduced a more equitable system of government, attempting to balance power between the national executive and local units, and to reduce the “winner-take-all” stakes of the presidency that had fueled ethnic tensions. Odinga’s role in this process solidified his image as a leader who could move from protest to policy – from opposing the status quo to helping build new institutions. It also showed his willingness to work within government (as Prime Minister) to achieve long-sought changes. However, implementing the new constitution’s ideals proved challenging, and entrenched political interests (including some allied to Odinga) occasionally impeded full realization of its promises (Wapukha, 2025). Still, the charter has largely endured, and devolution in particular has changed Kenya’s political landscape by empowering local governance – an outcome that aligns with Odinga’s long-term advocacy of “majimbo” (regional autonomy) inherited from his father’s era (Ssentamu, 2022).

Continued Opposition and the 2013 & 2017 Elections

With the new constitution in effect, Kenya held its next elections in March 2013. Raila Odinga, having served five years as Prime Minister, once again offered himself as a presidential candidate – his third attempt – under a coalition called CORD (Coalition for Reforms and Democracy). His main opponent was Uhuru Kenyatta, son of Jomo Kenyatta, who had allied with William Ruto (a former Odinga ally turned rival) under the Jubilee Alliance. The 2013 campaign was hard-fought but more peaceful than 2007, partly due to fear of a repeat of violence and the deterrent of International Criminal Court indictments looming over Kenyatta and Ruto for alleged roles in 2007 unrest. The election results showed Uhuru Kenyatta winning with about 50.5% to Odinga’s 43.7%. Odinga disputed the outcome, alleging irregularities, and filed a petition at the Supreme Court. Although the 2013 petition exposed some failures in the new electronic tallying system, the court ultimately upheld Kenyatta’s victory (Muthomi, 2025). Odinga publicly respected the court’s ruling, reinforcing the norm of legal contestation rather than street protests (Wapukha, 2025). He transitioned back into the role of opposition leader, using his platform to push for continuing reforms – including police reforms, electoral commission changes, and anticorruption measures – throughout Kenyatta’s first term. Odinga’s persistence in opposition demonstrated his commitment to accountability, but it also set the stage for yet another electoral showdown.

In August 2017, Raila Odinga made his fourth presidential run, this time heading the NASA (National Super Alliance) coalition against incumbent Uhuru Kenyatta (seeking a second term). When Kenyatta was again declared the winner (with 54% to Odinga’s 45%), Odinga challenged the results in court, citing technical and procedural flaws by the Independent Electoral and Boundaries Commission (IEBC). In a historic decision for African jurisprudence, Kenya’s Supreme Court nullified the 2017 presidential election due to irregularities, ordering a fresh vote within 60 days – a vindication of Odinga’s claims and a personal triumph in his quest for electoral justice (Wapukha, 2025). However, Odinga decided to boycott the October 2017 re-run election, asserting that the IEBC had not been sufficiently reformed to guarantee fairness. With Odinga’s supporters mostly staying home, Kenyatta easily won the low-turnout repeat poll. Political tensions ran high as Odinga’s camp refused to recognize the legitimacy of Kenyatta’s mandate. In a symbolic act of defiance, on January 30, 2018, Raila Odinga swore himself in at a public ceremony as the “People’s President,” claiming to embody the sovereign will of voters who, in his view, had been disenfranchised (Wapukha, 2025). This act challenged the state’s authority, but the government largely avoided confronting Odinga directly, perhaps wary of inflaming the situation.

Just when Kenya appeared to teeter on the brink of sustained instability, Raila Odinga once again made a surprising political pivot. On March 9, 2018, he and President Uhuru Kenyatta appeared together on the steps of Nairobi’s Harambee House and shook hands – a moment that instantly became known as “The Handshake.” This gesture signaled a rapprochement and launched the Building Bridges Initiative (BBI), a joint effort by Odinga and Kenyatta to address issues of national unity, electoral justice, and historical grievances (Kenyan History Team, 2025). The Handshake stunned both allies and adversaries. To Odinga’s supporters, it initially offered hope of reforms and an end to the exclusion of his constituency from power. The BBI process proposed significant constitutional amendments, including possibly expanding the executive to introduce a prime minister post and other changes ostensibly to make elections less zero-sum. However, the BBI constitutional amendment bill was ultimately struck down by the courts in 2021 for procedural improprieties, halting the initiative. In hindsight, Odinga’s 2018 pact with Kenyatta had ambiguous results. On one hand, it calmed the post-2017 turmoil and showed Odinga’s statesmanship in prioritizing stability and unity. On the other hand, it arguably weakened Kenya’s opposition by aligning its chief leader with the government. Critics like Wapukha (2025) argue that the Handshake was a “betrayal of the people” done through elite deal-making without public consultation, and that it served Odinga’s personal political interests (such as securing Kenyatta’s backing for a future run) at the expense of robust oversight of government. As had happened before, Odinga faced accusations of forsaking principle for power – an enduring controversy of his career.

The 2022 Election and Aftermath

Raila Odinga’s fifth presidential bid came in 2022 under the Azimio la Umoja-One Kenya coalition. This time, in a remarkable realignment, Odinga enjoyed the open support of outgoing President Uhuru Kenyatta – the former rival with whom he had reconciled. The election essentially became a contest between Odinga (now backed by the state machinery and many establishment figures) and William Ruto, the sitting Deputy President who cast himself as the anti-establishment “hustler” candidate. Odinga chose Martha Karua, a respected female former justice minister, as his running mate, marking a historic first of a major coalition nominating a woman for Deputy President. The campaign themes were sharply drawn: Odinga ran on anti-corruption, continued infrastructure development, and unity (hence “Azimio la Umoja,” Swahili for “Resolution for Unity”), while Ruto attacked Odinga and Kenyatta as dynastic elites, positioning himself as a champion of the ordinary citizen against the “handshake brothers” (Ssentamu, 2022).

The August 9, 2022 election was extremely close. William Ruto was declared the winner with about 50.5% of the vote to Odinga’s 48.8%, a margin of under 2 percentage points (Ssentamu, 2022). Odinga rejected the results, alleging serious irregularities and even presenting dramatic claims of a “stolen victory.” He filed a petition at the Supreme Court, as in prior races. However, the 2022 Supreme Court unanimously upheld Ruto’s win, finding that some evidence presented by the Odinga team was falsified and that the electoral process, despite some hitches, met the constitutional threshold (as documented in the court’s judgment; see Remtula, 2022). Accepting the verdict, Odinga begrudgingly moved once more into opposition. At 77 years old, he found himself rallying supporters to protest the outcome and the new government’s policies, particularly criticizing Ruto’s administration for raising taxes and the high cost of living. In early 2023, Odinga organized a series of demonstrations pressing for electoral accountability and economic relief, which occasionally led to unrest and clashes with police.

Yet, true to pattern, by mid-2023 and into 2024 Odinga was engaging in dialogue with President Ruto. The two began behind-the-scenes talks, and by April 2024 they struck a political understanding (Reuters, 2025). In a development reminiscent of the Handshake, Odinga and Ruto agreed to cooperate on certain national issues. This was formalized in a March 2025 Memorandum of Understanding between Odinga’s ODM party and Ruto’s ruling UDA party to work together in a “bipartisan” framework (Muthomi, 2025). Both sides insisted this was not a formal coalition or merger, but effectively it pacified the opposition. For many Kenyans, it appeared that Odinga had once again opted to join forces with the government of the day. While this pact might bring short-term stability and a share of influence for Odinga’s camp, it also meant Kenya lacked a strong opposition voice holding the government accountable (Reuters, 2025). Among a new generation of Kenyans – the so-called “Gen-Z” youth – frustration with political deal-making boiled over. During protests in 2024, some young demonstrators even implored the aging Odinga to “please go home” (telling him “Baba, kaa nyumbani”) – a striking sign of how his long career of struggle had begun to meet calls for retirement (Wapukha, 2025). Odinga’s final political moves thus generated debate: was he securing peace and incremental progress, or simply perpetuating a cycle of elite bargaining that left the root problems unresolved?

Legacy and Ongoing Impact

Raila Odinga’s legacy in Kenya is profound and multifaceted. As a pro-democracy crusader, he is credited with helping usher in the end of one-party rule in the early 1990s and becoming a symbol of the “Second Liberation.” He endured detention, torture, and exile in the fight against autocracy, which turned him into, as one writer described, “a symbol of endurance” and the face of resistance to Moi’s dictatorship (Wapukha, 2025). Because of leaders like Odinga, Kenya transitioned to a multiparty system, expanded freedom of expression, and empowered civil society – changes that have had lasting effects on Kenyan political culture. Odinga’s role in achieving the 2010 Constitution also stands out. The constitution’s progressive provisions (such as devolution and a stronger framework for rights) have reconfigured governance, bringing resources and decision-making closer to the people. Odinga’s supporters often hail him as “the father of Kenyan democracy” or “the People’s President” for these contributions.

At the same time, Odinga’s career has been marked by controversies and contradictions that complicate his saintly image. Throughout five presidential defeats, he consistently alleged fraud – fostering a narrative among his base that he was denied victory by a conspiracy of “system” insiders. Critics argue that this pattern, while sometimes justified, also entrenched a sense of perpetual grievance and could inflame ethnic divisions (Reuters, 2025). Indeed, Odinga has faced accusations of exploiting ethnic loyalties for political gain. For example, in the aftermath of contested polls like 2007 and 2017, ethnic clashes occurred largely aligning with support for Odinga versus his rivals. Odinga himself has decried tribalism and called for unity, but opponents claim his campaign rhetoric at times reinforced the Luo vs. Kikuyu rivalry or pitted “marginalized communities” against “Mount Kenya elites.” These ethnic undertones in Kenyan politics are rooted in historical injustices and the Kenyatta-Odinga feud of the 1960s (Opondo, 2014), but they remain a sensitive part of Odinga’s legacy. It is noteworthy that Odinga has also drawn support from many other ethnic groups and formed broad coalitions – indicating he is not solely an ethnic leader, but the ethnic element of his following cannot be ignored.

Another controversy is Odinga’s tendency to make political U-turns and elite bargains. From cooperating with Moi (2001), Kibaki (2008), Kenyatta (2018) to Ruto (2024/25), each partnership raised eyebrows. Detractors see a pattern of “self-aggrandizement” (Wapukha, 2025) – suggesting that Odinga has sometimes put personal power ambitions over consistent principles. The 2018 Handshake with Uhuru Kenyatta, while easing national tensions, also effectively nullified formal opposition for the remainder of Kenyatta’s term. Some former supporters felt betrayed that Odinga stopped pressing for deeper electoral justice after securing a truce. Similarly, the understanding with Ruto in 2024–25 left many questioning if Odinga was defanging opposition yet again in exchange for some influence or protections. Odinga’s defenders counter that such compromises are part of Kenya’s political reality and that Odinga has used these avenues to push incremental reforms from within. They also note his remarkable ability to let “enemies” become allies – reflecting a forgiving nature and focus on the bigger picture (Reuters, 2025). This duality – idealistic reformer and hard-nosed dealmaker – makes Odinga an “enigma,” as one biographer termed him (Badejo, 2006).

Impact on political identity: Raila Odinga has undeniably shaped Kenyan political identity in several ways. For his followers, he embodies the struggle against oppression and the hope for a more equitable nation. His personal narrative of sacrifice (years in detention) and persistence (never giving up on the presidency) resonates deeply, especially in regions that felt historically excluded from power. The moniker “Baba” reflects how many view him as a paternal figure of the nation’s democratic journey. He has cultivated a mythology around himself – for instance, embracing nicknames like the “People’s President” and alluding to biblical analogies (his 2017 campaign called him “Joshua” leading Kenyans to the promised land) – which speaks to a broader phenomenon of political self-mythologizing (Wesa, 2024). This mythic status has sometimes made it hard for his movement to transition to new leadership. It also raises questions about the line between popular hero worship and critical civic engagement.

On the national stage, Odinga’s prominence has forced conversations about inclusion, constitutionalism, and the true meaning of democracy. His rivalry with figures like Uhuru Kenyatta and William Ruto also reflected and reinforced the narrative of dynasties versus hustlers – Odinga himself, despite his anti-establishment posture, is part of a political dynasty as Oginga Odinga’s son, something Ruto exploited by branding Odinga and Kenyatta as the “dynasties” (Ssentamu, 2022). Thus, Odinga’s story is entwined with Kenya’s exploration of national identity: are politics driven by issues and institutions, or by personalities and ethnic lineage? While Kenya has not fully answered that, Odinga’s career highlights both the progress and pitfalls.

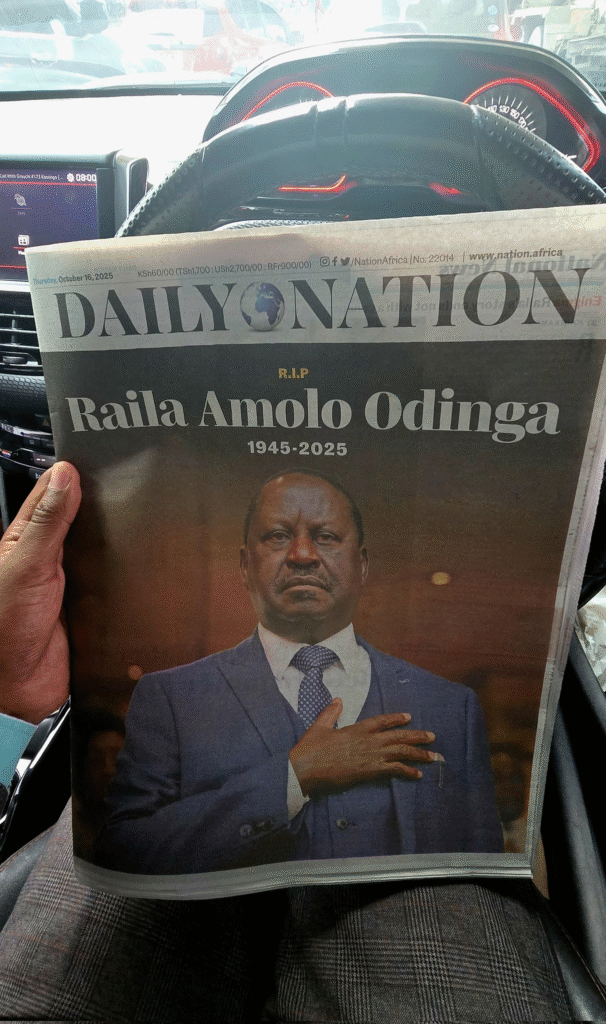

In October 2025, Raila Odinga passed away at the age of 80, after a lifetime in the political arena. The outpouring of grief across the country – from Nairobi’s Kibera slums to his rural Nyanza backyard – demonstrated the affection and respect he earned, even among those who never saw him attain the presidency. Hundreds poured into the streets, waving twigs (traditional symbols to ward off evil) and mourning the “fallen giant” of Kenyan politics (Reuters, 2025). Odinga leaves behind a complicated but indelible legacy. As a democracy advocate, reformist, and opposition stalwart, he helped shape a more open Kenya. As a power player, he also exemplified the compromises of Kenyan politics, where ethnic considerations and elite pacts often undercut pure ideals.

Future historians will likely debate Raila Odinga’s record for years to come. Yet few would dispute that he played a central role in modern Kenyan history, earning a place among the country’s most influential figures. In the words of one scholar, Odinga’s political longevity owes much to the “powerful myths and narratives that surround him,” but also to genuine accomplishments in expanding Kenya’s democratic space (Wesa, 2024). His impact endures in the institutions he fought to reform and the generations he inspired to believe in the promise of change.

Read Next on KenyanHistory.com:

- The Birth and Evolution of Kenya’s Multiparty Democracy

- Majimbo Dreams: Kenya’s Lost Federalism

- 30 Images from Kenya’s 1982 Failed Coup

References

Badejo, B. A. (2006). Raila Odinga: An Enigma in Kenyan Politics. Lagos: Yintab Books.

Muthomi, K. (2025, October 15). Raila’s Political Journey: From detention to one of Kenya’s most influential political figures. Kenyans.co.ke. (online news article)

Opondo, P. A. (2014). Kenyatta and Odinga: The harbingers of ethnic nationalism in Kenya. Global Journal of Human-Social Science: History, Archaeology & Anthropology, 14(3), 15–25.

Reuters. (2025, October 15). Kenya’s veteran opposition leader Raila Odinga dies at 80. Reuters News. (International news report)

Remtula, J. (2022). Raila Odinga vs William Ruto – Presidential Election Petition 2022: Supreme Court of Kenya Judgment. (Court judgment analysis).

Ssentamu, M. (2022). Raila Odinga: An Unexpected Path to Power. [Unpublished manuscript]. Makerere University, Uganda.

Wandati, A. (2019). The Midas touch in Kenya’s politics: Explaining Raila’s permanent political relevance. (Independent analysis on Academia.edu).

Wapukha, P. J. (2025). From a Tiger to a Cat: How and Why Raila Odinga betrayed the liberation cause 35 years later. Democracy in Africa. (online commentary)

Wesa, S. (2024). The self-mythologization of Raila Odinga in Kenyan politics. East African Journal, 5(1), 45–58