Long before Nairobi became a city of traffic jams and ride-hailing apps, its roads told a different story. The matatu — a Swahili slang for “three cents,” the original fare — began as a hustler’s innovation and grew into Kenya’s loudest form of street art. This gallery traces that journey from the dusty streets of the 1950s to the graffiti-glazed vans of the 1990s — when matatus were more than transport; they were moving declarations of freedom, rebellion, and creativity.

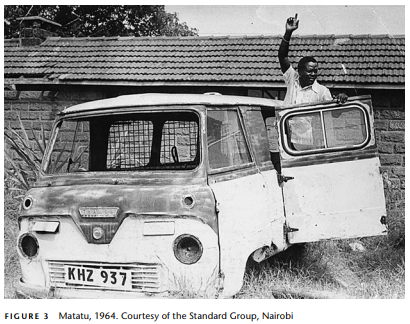

The Birth of the Matatu (1950s–1960s)

Private pickups and taxis begin carrying passengers for a few coins. Authorities label them illegal, but demand grows.

1950s Matatu

1960s Matatu

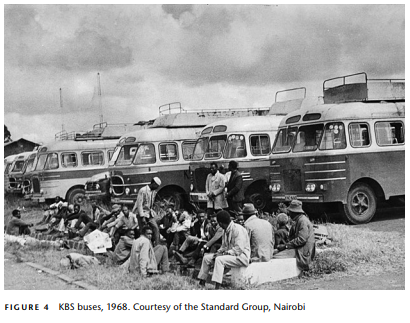

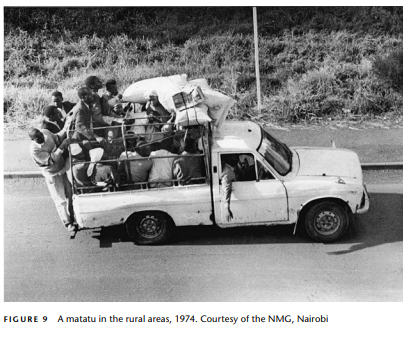

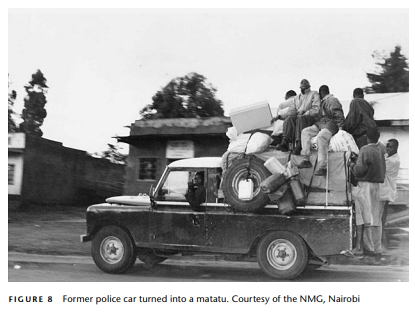

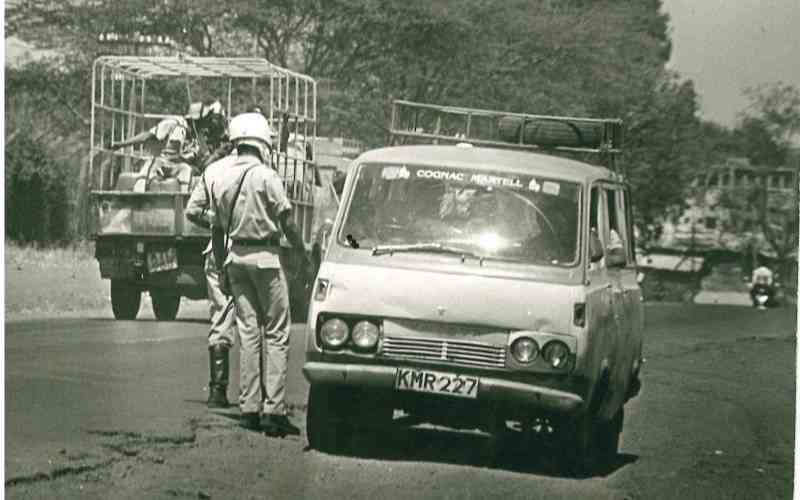

1970s Matatus

The post-independence boom turns matatus into the heartbeat of Nairobi’s streets. Datsuns and Peugeots race across the city as police crackdowns intensify.

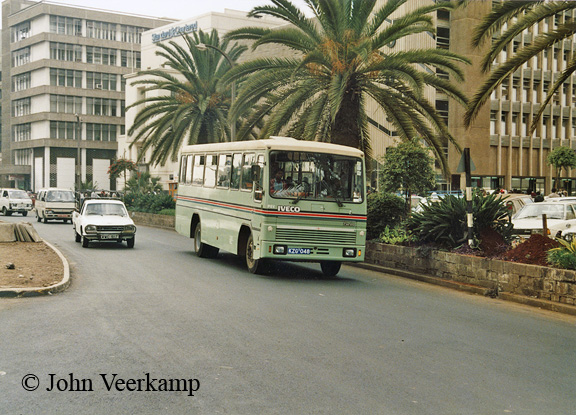

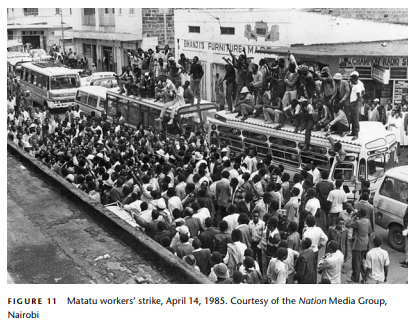

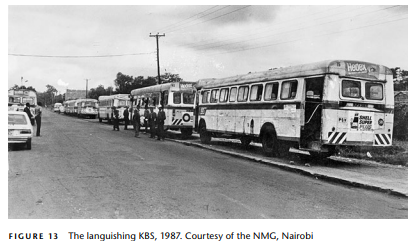

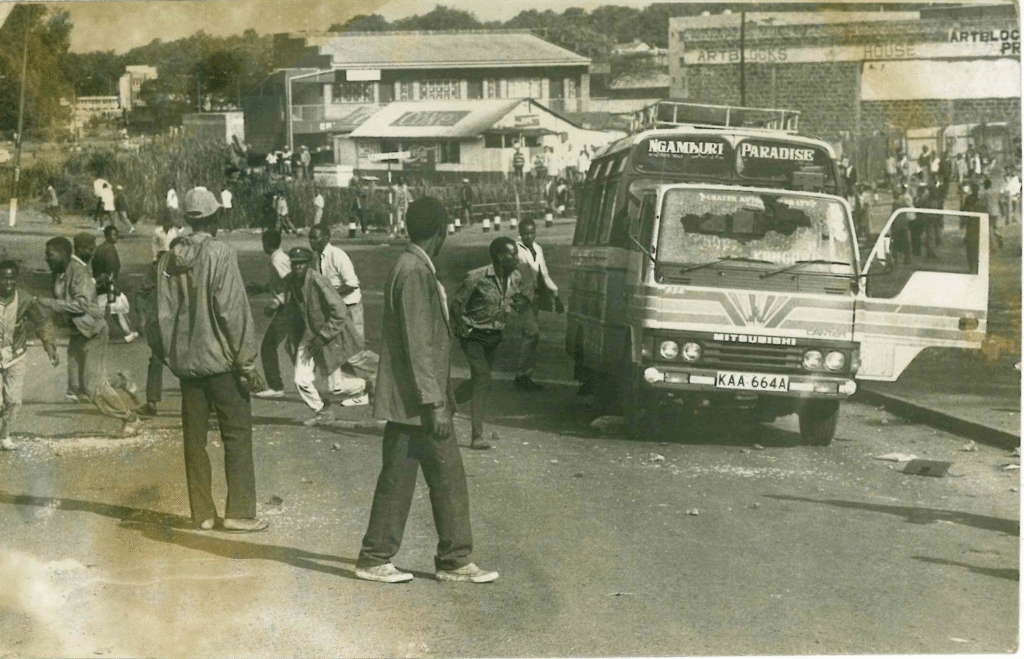

1980s Matatu

Matatus evolve into cultural billboards. Faces of reggae stars, African leaders, and football icons decorate every panel. Music thunders from custom speakers.

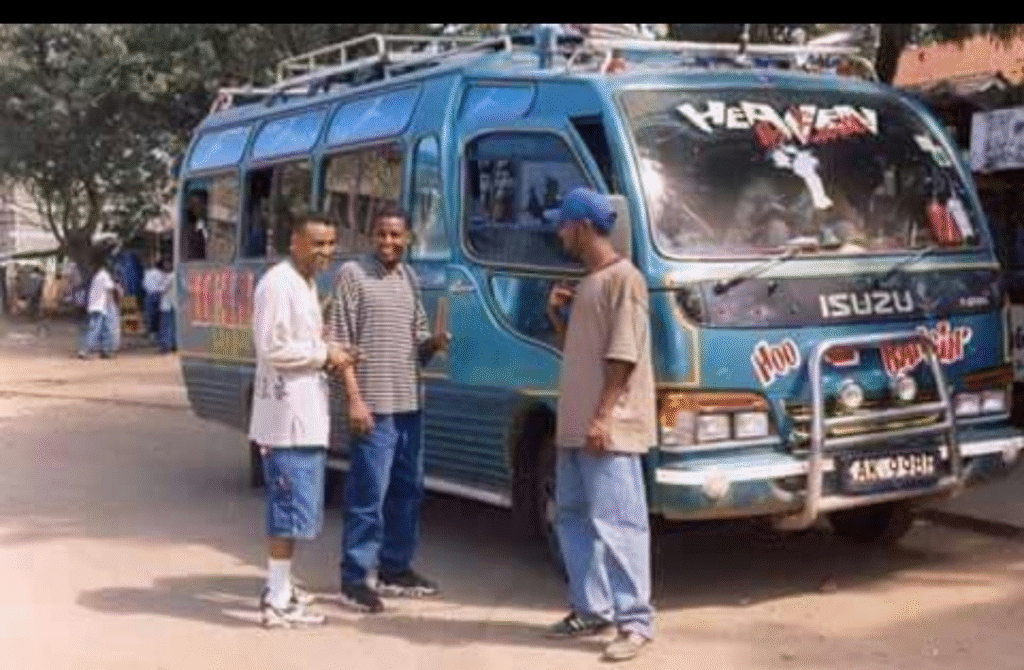

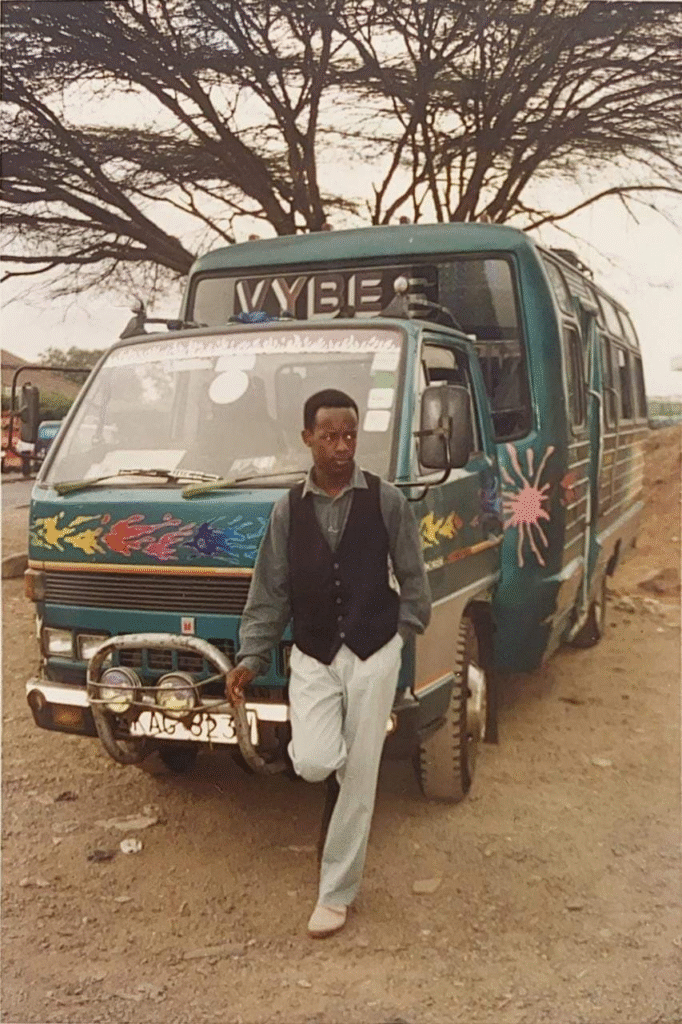

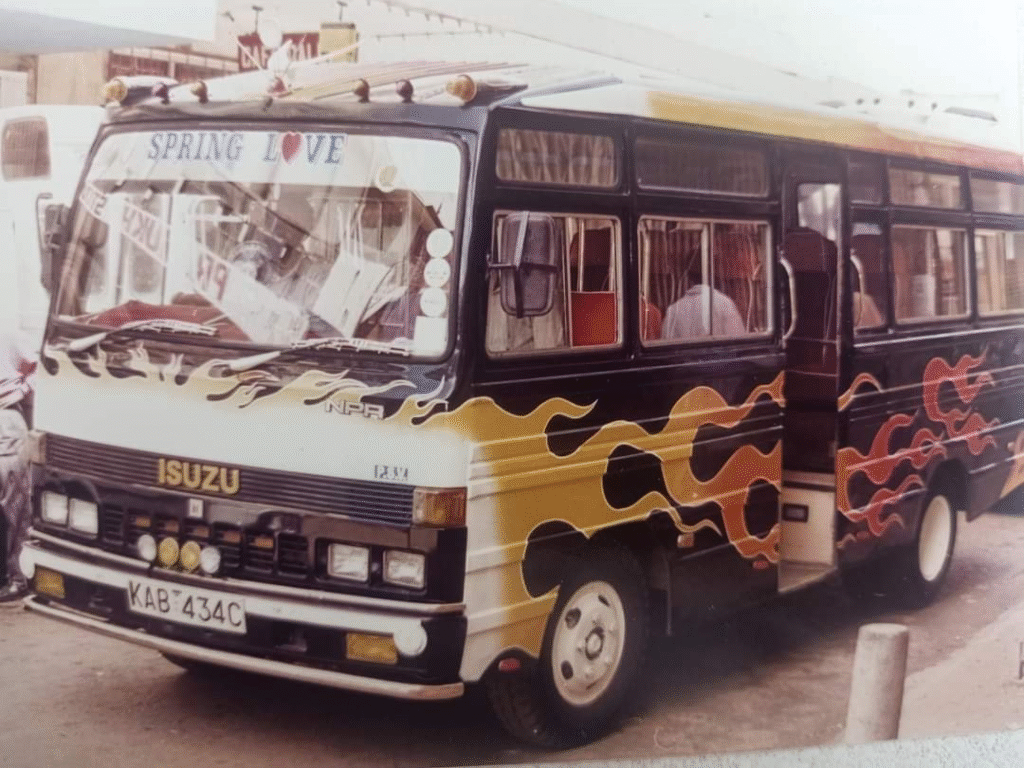

1990s Matatus

Matatus in 2000s

Government reforms under Minister John Michuki impose order — uniforms, seatbelts, and the famous yellow line. Creativity fades, then returns with the Nganya Awards celebrating artistic matatus.

2010s Matatu

Digital mapping, Wi-Fi, and LED murals make Nairobi’s matatus global icons again. They blend technology with design, keeping the art alive.

Each matatu carries a fragment of Nairobi’s story — the struggle for mobility, the celebration of self-expression, and the rhythm of the city itself. From painted slogans to thundering beats, Kenya’s public transport remains one of its most creative social spaces — proof that even in traffic, the art keeps moving.