In the 1950s, the British Empire fought its final and most violent colonial war in Kenya. What began as a counterinsurgency against the Mau Mau uprising turned into one of the largest systems of mass detention in modern imperial history. Between 1952 and 1960, colonial authorities confined over a million Kikuyu, Embu, and Meru people in camps and fortified villages under the guise of “rehabilitation.” The official term was Emergency detention; the reality was a network of forced labor, torture, and psychological reconditioning that mirrored the logic of twentieth-century concentration camps.

For decades, Britain portrayed the Emergency as a “civilizing mission” that saved Kenya from barbarism. Yet, evidence from declassified colonial archives and survivor testimony reveals a different story—a bureaucracy of brutality designed to break African resistance and preserve white rule (Elkins, 2005; Anderson, 2005).

The Legal Machinery of Repression

The origins of Kenya’s detention system lay in the Emergency Regulations enacted on October 20, 1952. Governor Sir Evelyn Baring declared a state of emergency following a series of assassinations attributed to Mau Mau fighters. These laws empowered the colonial government to arrest and detain individuals without trial, censor the press, and confiscate property.

As Duffy (2015) notes, the emergency laws were not temporary war measures but an entire legal infrastructure that transformed Kenya into a carceral colony. Detention orders required no judicial review; appeals were meaningless. The British called it “preventive detention,” but it was, in practice, indefinite incarceration.

Colonial officials classified detainees into “hardcore,” “grey,” and “white” categories depending on their perceived loyalty. The goal, as articulated by the Colonial Office, was to “rehabilitate” Africans through confession, punishment, and labor—a psychological war as much as a military one (Duffy, 2015).

The Pipeline: Engineering Obedience

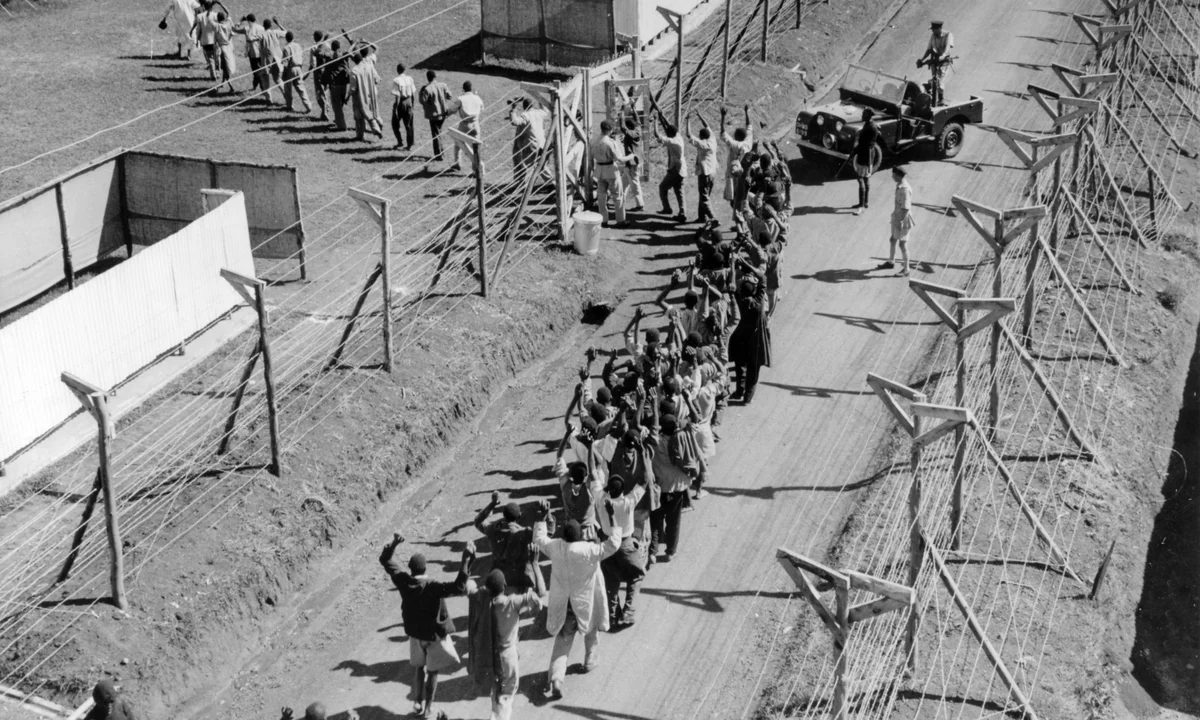

The heart of this system was what British officers called “the Pipeline.” It was a network of more than 100 camps and so-called “protected villages” stretching from Nairobi to the Rift Valley. The Pipeline was both literal and ideological—an assembly line through which detainees were processed, punished, and “reformed.”

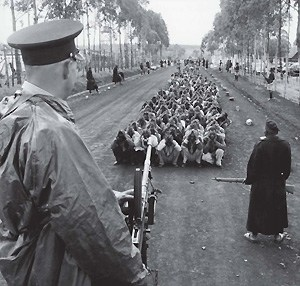

Popławski (2024) describes it as a colonial machine designed to reorder society by breaking individuals. Detainees entered the system through screening centers—temporary sites where interrogators extracted confessions using beatings, water torture, and sexual humiliation. Those deemed “recalcitrant” were sent to maximum-security camps like Manyani, Athi River, and Manda Island, while others moved gradually to lower-tier “rehabilitation” camps such as Langata and Ruringu.

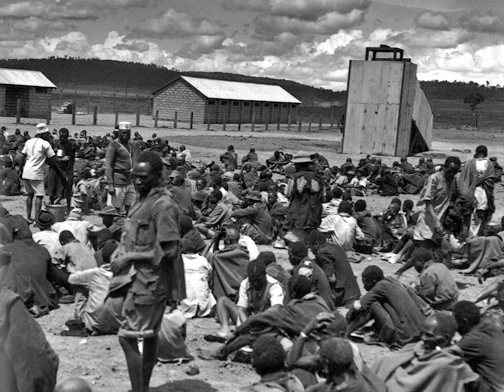

By 1954, the Pipeline held more than 70,000 detainees. Outside the wire, another 1.2 million civilians—mostly Kikuyu—were forcibly relocated into villagization schemes. These “protected villages,” surrounded by barbed wire and trenches, were concentration camps in all but name (Elkins, 2005). The British described them as “for the Kikuyu’s own safety.” In truth, they were designed to sever Mau Mau supply lines, destroy communal networks, and enforce collective punishment.

Inside the Pipeline, rehabilitation took the form of forced labor and ideological re-education. Prisoners were made to dig trenches, build roads, or cultivate colonial farms under military supervision. Guards demanded daily confessions and public oaths of loyalty. Anderson (2005) writes that the process was meant to “break the African mind” through humiliation and exhaustion.

The Camps of Pain

Among the most infamous detention centers was Hola Camp, located in the arid Tana River region. Established for detainees labeled “uncooperative,” Hola became a symbol of the system’s cruelty. On March 3, 1959, guards killed eleven prisoners who refused to work. The colonial government initially claimed they had “died from drinking contaminated water,” but an autopsy revealed blunt-force trauma.

The Hola Massacre shattered Britain’s moral defense of empire. Reports by the British press and parliamentary debates forced the Colonial Office to admit that “excessive force” had been used. Yet, as Duffy (2015) demonstrates, no senior officials faced trial. The killings were treated as administrative misconduct rather than state-sanctioned murder.

Other camps were no less brutal. At Mwea, detainees were subjected to beatings, electric shocks, and castration. At Embakasi, near Nairobi, they were forced to construct the city’s airport runway—labor literally used to build colonial infrastructure. Women detained in Kamiti and Gitamayu faced sexual assault and forced nudity during interrogations. These atrocities were not rogue acts of cruelty; they were embedded in policy, systematically reported through the administrative chain (Elkins, 2005).

The Bureaucracy of Violence

What made the Kenyan detention system uniquely insidious was its bureaucratic precision. The Colonial Office maintained detailed files on every detainee’s progress, documenting confessions, punishments, and psychological assessments. Duffy (2015) refers to this as the “paper architecture of empire,” a system that sanitized torture into forms and checklists.

One of the most notorious architects was Terence Gavaghan, District Commissioner and Rehabilitation Officer for Central Province. His “dilution technique”—a euphemism for breaking prisoners through isolation and group punishment—became standard practice across camps. Gavaghan’s reports described “recalcitrant” detainees as “dregs of Mau Mau,” a term revived decades later in British archives to rationalize collective brutality (Boende, 2023).

The language of rehabilitation masked the reality of terror. “Screening,” for instance, meant beating; “progressive stages” meant submission under duress. By 1958, colonial officers openly acknowledged that violence was necessary to sustain control. Popławski (2024) calls this a “continuum of violence,” linking Kenya’s camps to those used in earlier imperial conflicts such as South Africa’s Boer War and later systems of counterinsurgency in Malaya and Cyprus.

Silence and the Hanslope Files

When Kenya gained independence in 1963, Britain destroyed or secretly shipped thousands of colonial records to the UK. The goal, according to Duffy (2015), was to erase legal evidence that could implicate the empire in crimes against humanity. The remaining files were labeled “Migrated Archives” and hidden for decades in a government repository at Hanslope Park.

The silence held until 2011, when the discovery of the Hanslope Files during a lawsuit by Mau Mau veterans forced Britain to confront its past. The plaintiffs—Ndiku Mutua, Wambugu wa Nyingi, and Jane Muthoni Mara—testified that they had been tortured by colonial officers. The case, Mutua and Others v. Foreign and Commonwealth Office (2013), marked a turning point.

For the first time, the British government acknowledged the abuse of detainees. Foreign Secretary William Hague issued a formal statement of “regret” and announced a compensation package of £19.9 million to 5,228 survivors. But, as Duffy (2015) notes, the apology was carefully worded to avoid legal liability. The state admitted cruelty but not responsibility.

The Hanslope disclosures revealed that officials in London had not only known about the torture but had advised colonial officers on how to conceal it. This exposure reframed the Emergency not as an African rebellion suppressed by necessity, but as an imperial crime meticulously documented and later denied.

Continuity After Empire

The story of Kenya’s concentration camps did not end with independence. Popławski (2024) demonstrates that the architecture of colonial counterinsurgency persisted in postcolonial Kenya. During the Shifta War (1963–1967) in the north, the government employed similar tactics—forced relocations, screening centers, and collective punishment—against Somali insurgents.

This continuity underscores a broader truth: decolonization did not dismantle the machinery of control; it transferred it. The same laws and administrative habits that justified British detention were inherited by new African states grappling with dissent and insecurity. Kenya’s own political prisons during the Moi era echoed the same logic of “rehabilitation through detention.”

Reckoning with Empire

The exposure of Britain’s concentration camps forced a moral reckoning both in Kenya and the United Kingdom. In Kenya, the story of the camps remained suppressed for decades. Many postcolonial leaders were former “loyalists” who had collaborated with the colonial state. Acknowledging the camps would have meant reopening the question of legitimacy.

It took the work of historians such as Caroline Elkins and David Anderson, combined with the testimony of survivors, to restore the truth. Elkins (2005) estimates that up to 1.5 million people were confined or displaced during the Emergency. While her figures remain debated, even conservative estimates confirm a vast apparatus of repression unprecedented in Britain’s late empire.

In Britain, the revelations sparked parliamentary debates and academic reflection. Yet, the narrative of the “benevolent empire” persists. The Hola killings, the torture at Manyani, and the starvation in villages are often framed as “excesses” rather than systemic violence. Duffy (2015) challenges this view, arguing that the camps were not deviations but central to Britain’s imperial model of governance—discipline disguised as development.

Legacy and Memory

Today, the remnants of the camps—crumbling walls, rusted barbed wire, overgrown graves—stand as silent memorials to a war the empire tried to forget. In Hola, a small monument now honors the eleven men killed in 1959. At Manyani, local activists are pushing for the site to become a national museum. For the descendants of detainees, the struggle is not only about memory but recognition: a demand that the pain of the past be seen as part of Kenya’s national story, not its shame.

The camps also continue to haunt British identity. In 2022, as debates about empire resurfaced in British politics, historians reminded the public that the “moral empire” ended not with benevolence but with barbed wire. Kenya’s Emergency shattered the illusion that the British Empire withdrew gracefully. It withdrew under the weight of its own brutality.

As Popławski (2024) concludes, the concentration camps in Kenya were not anomalies of colonial panic—they were the logical culmination of imperial control, where law, violence, and ideology fused into one. The British built them to preserve order but left behind a legacy of trauma that outlived empire itself.

References

Anderson, D. (2005). Histories of the hanged: Britain’s dirty war in Kenya and the end of empire. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Boende, J. (2023). “The dregs of the Mau Mau barrel”: Rhetoric and racism in late colonial Kenya. Warwick African Review of Politics, 4(1), 77–99.

Duffy, A. (2015). Legacies of British colonial violence: Viewing Kenyan detention camps through the Hanslope disclosure. London Human Rights Review, 14(2), 109–128.

Elkins, C. (2005). Imperial reckoning: The untold story of Britain’s gulag in Kenya. New York: Henry Holt.

Popławski, B. (2024). Continuum of violence: Concentration camps in Kenya and postcolonial echoes. Warsaw Journal of African Studies, 30(2), 214–236.