If cities had nine lives, Mombasa would be on its fifteenth. It has been razed, looted, and conquered so many times that by all logic it should have drowned in the Indian Ocean centuries ago. Yet it endures — stubbornly, defiantly, perched on its coral island like a cat that refuses to die. Every empire that came here thought it had claimed Mombasa for good. The Portuguese built their fortress, the Omanis flew their flag, the British planted their Union Jack. Each left scars, but none erased the city.

The City That Refuses to Sink

Mombasa is not a footnote in someone else’s story. It is one of the oldest continually inhabited cities on the East African coast, a thousand-year-old port where Swahili traders bartered ivory and gold for Persian cloth and Chinese porcelain. It has been a marketplace, a battlefield, and a crossroads of empires. To understand Kenya’s history, you cannot start in Nairobi’s swamp; you must start here, on the coral stone and salt air of Mombasa.

Swahili Foundations (1000–1500)

Long before Vasco da Gama’s ships cut across the horizon in 1498, Mombasa was already a city of the sea. By the 11th century, it was one of several Swahili city-states along the East African coast, linked not by borders but by the monsoon winds. For six months of the year, the wind blew ships from Arabia, Persia, and India toward Mombasa; six months later, it carried them back. This rhythm created a world where Africans, Arabs, Persians, and Indians were not strangers but trading partners, neighbors, and sometimes family.

The Swahili language itself is proof of this entanglement — a Bantu tongue written in Arabic script, peppered with words from across the Indian Ocean. In Mombasa, merchants dealt in ivory, tortoise shell, and gold from the African interior. In return, they brought in silks, ceramics, and spices. Archaeological finds show shards of Chinese porcelain buried in coral houses, evidence that Mombasa was never isolated.

Religion traveled with trade. Islam arrived early, and by the 12th century mosques were rising along the coast. Mombasa’s old mosques, built of coral stone and lime, were not just places of worship but markers of identity: this was a city of Islam, connected to Mecca and the wider Muslim world. The call to prayer echoed across the island long before church bells rang in Nairobi.

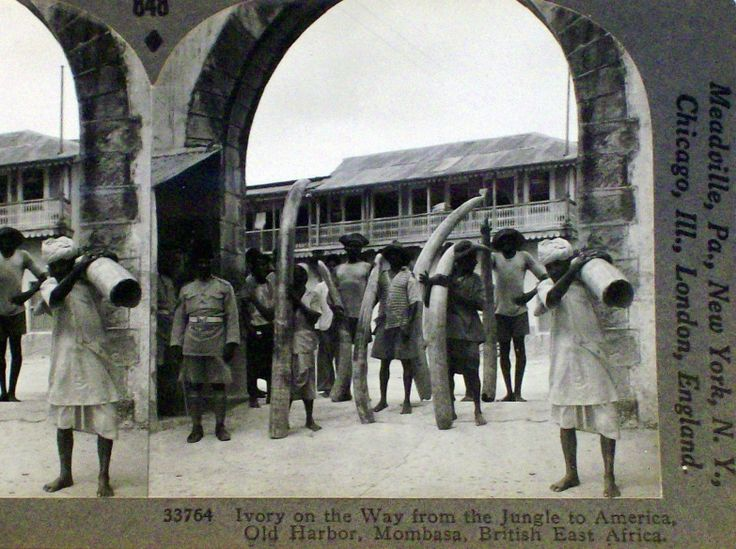

But Mombasa was not a utopia. It was also part of the Indian Ocean slave trade. Enslaved Africans were exported across the ocean, sold in Arabian, Persian, and Indian markets. The same dhows that carried porcelain and spices also carried human cargo. For centuries, Mombasa thrived as both a cultural crossroads and a site of human exploitation.

By the 15th century, Mombasa was a jewel of the Swahili coast: cosmopolitan, wealthy, and self-confident. But its fortune drew predators. When the Portuguese rounded the Cape of Good Hope and pushed into the Indian Ocean, they did not find an empty coast waiting to be discovered. They found Mombasa, a city that had been trading for half a millennium. And they set about trying to break it.

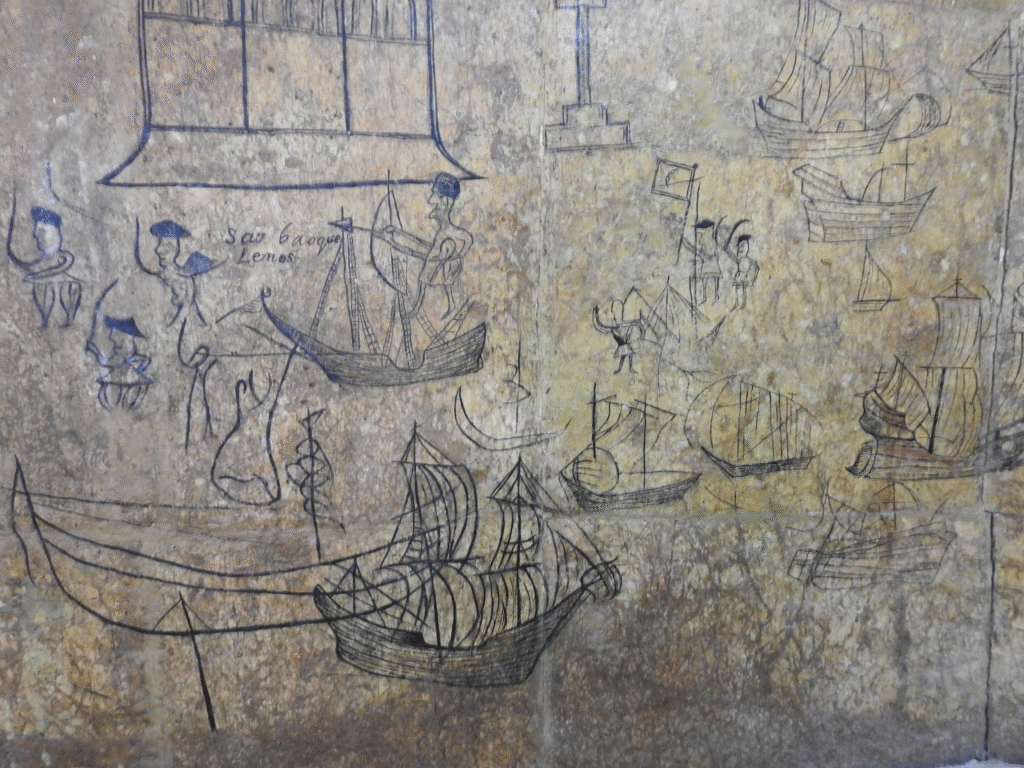

The Portuguese Invasion (1593–1698)

The Portuguese did not arrive in Mombasa looking for friends. When Vasco da Gama’s fleet docked in 1498, the Swahili city-states were already centuries old, but to the Portuguese, they were pawns in a chessboard stretching from Lisbon to Goa. The Indian Ocean was a lucrative highway, and whoever controlled it would control the world’s spice trade.

Mombasa quickly learned what this meant. In 1505, the Portuguese bombarded the city, killing hundreds and burning homes. They returned again in 1528 and 1588, leaving fire and rubble in their wake. To Lisbon, these raids were “pacification.” To Mombasa, they were massacres.

In 1593, the Portuguese decided to plant something more permanent: Fort Jesus, a looming coral-stone fortress built on the edge of the island. Its name was a declaration of intent — the cross would watch over the harbor, and Mombasa would serve as a Portuguese outpost in the East. The fort was an architectural marvel, designed by Giovanni Battista Cairati, and today it still stands as a UNESCO World Heritage site. But to the people of Mombasa, it was a cage.

The Portuguese ruled with a heavy hand. Taxes were extortionate, trade was strangled, and local rulers were treated as subordinates. The city’s prosperity waned under their grip. Mombasa became less a hub of free trade and more a checkpoint on a European empire’s supply line. Resistance flared repeatedly. Local leaders, often in alliance with the Sultan of Oman, staged uprisings that saw the fort besieged again and again.

The Portuguese responded with characteristic brutality. In 1631, the Sultan of Mombasa, Yusuf bin Hasan, led a revolt, killing Portuguese residents and briefly expelling them. But the Portuguese returned with overwhelming force, massacred the population, and reasserted control. For decades, the city was caught in this cycle: rebellion, reprisal, rubble.

By the late 17th century, the Portuguese grip was weakening. Their empire was overstretched, and rivals were circling. The Omanis, maritime powers from the Arabian Peninsula, saw their chance. In 1696, they laid siege to Fort Jesus. For almost three years, the fort held out, but starvation and disease ravaged the garrison. In 1698, the Omanis finally broke through. The Portuguese survivors surrendered, and Mombasa passed into Omani hands.

The Portuguese left behind little but scars: the walls of Fort Jesus, a battered city, and the memory of fire. For Mombasa, it was yet another invasion survived. But survival here was never gentle — it always came at a cost.

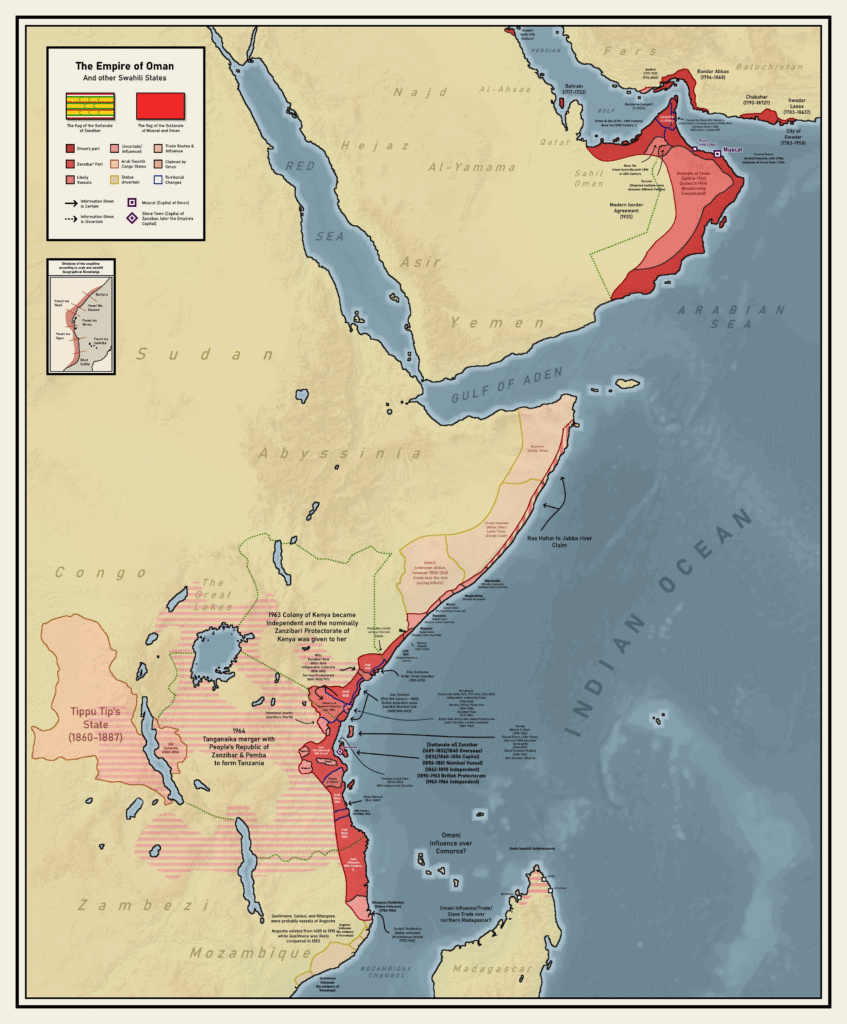

Omani Rule (1698–19th Century)

When the Portuguese flag finally fell over Fort Jesus in 1698, the Omanis walked in as liberators. For the people of Mombasa, who had endured a century of bombardments and massacres, the shift felt like fresh air after a chokehold. But liberation on the Swahili coast was always a relative thing. The Omanis came not to restore freedom but to redirect the flow of wealth.

Under Omani rule, Mombasa was folded back into the older networks of the Indian Ocean world. Trade revived. Dhows once again carried ivory, spices, and cloth across the monsoon routes. The city regained some of its prosperity, though always under the shadow of the Omani garrison in Fort Jesus. The Portuguese had built the fort to dominate; the Omanis kept it for the same reason.

By the 18th century, Omani influence stretched across the coast, but it was a loose grip. Local Swahili elites often ran the show day to day, paying tribute to Muscat while managing their own affairs. Mombasa remained proud, cosmopolitan, and occasionally rebellious. Control of the city switched hands several times as local rulers, Omanis, and even briefly the Mazrui family fought for dominance. The fort changed flags so often it became a kind of scoreboard for whoever was winning that year.

The real shift came in the 19th century, when the Sultan of Oman, Seyyid Said, moved his court from Muscat to Zanzibar in 1832. Mombasa became a satellite in this new order, important but no longer central. Zanzibar blossomed into the spice capital of the Indian Ocean, while Mombasa became one of its feeder ports.

But with this prosperity came darkness. The Omani economy of the 19th century ran on slavery. Enslaved Africans were marched from the hinterlands through caravan routes, sold in Zanzibar’s slave markets, and shipped across the ocean. Mombasa was both a transit point and a holding pen in this trade. Entire generations were uprooted, their labor and lives fueling the clove plantations of Zanzibar and the wealth of the Omani elite.

By the mid-19th century, European powers were circling again. Britain, increasingly dominant in the Indian Ocean, began pressing for abolition of the slave trade. Officially, the Omanis signed treaties to restrict it; in reality, the trade continued, often under Mombasa’s nose. The city once again found itself caught between empires — a Swahili hub trying to survive while outsiders decided its fate.

For two centuries, Omani rule gave Mombasa both revival and ruin: the return of trade, but also the entrenchment of slavery; local autonomy, but always under foreign suzerainty. It was a reminder that Mombasa’s history was never about peace. It was about endurance — living on between one empire’s retreat and another’s arrival.

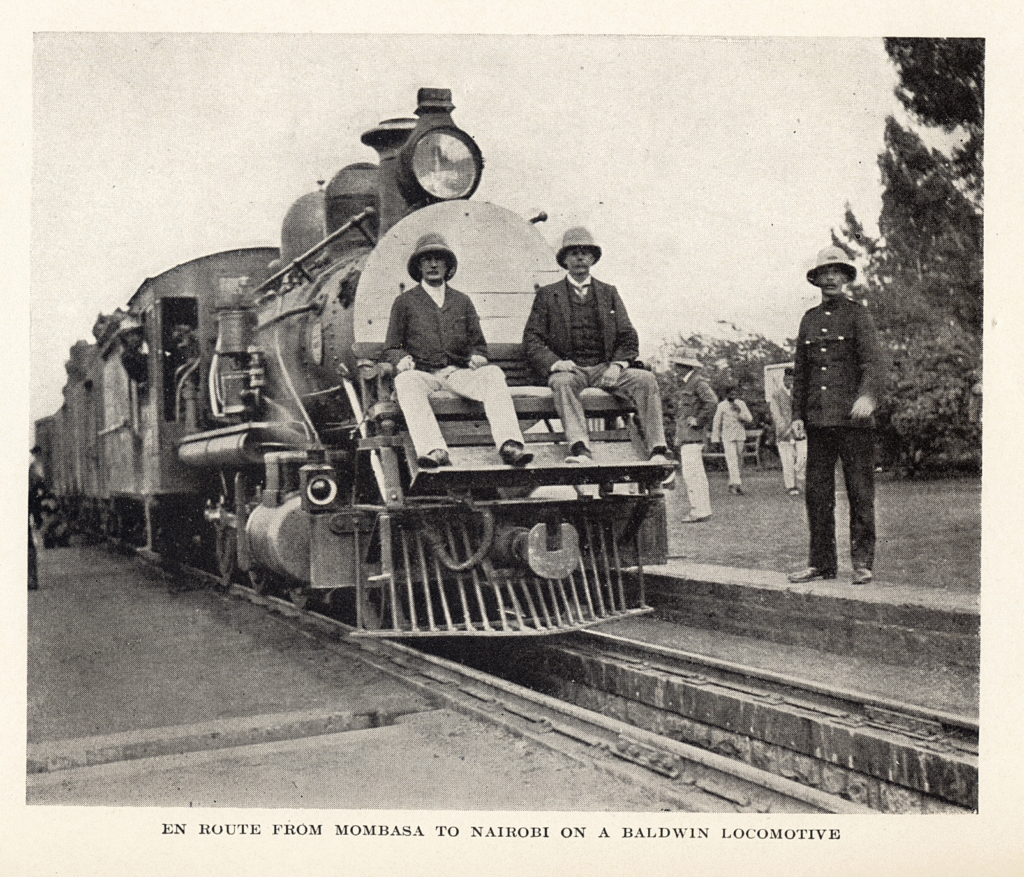

The British & Imperial Real Estate (19th–20th Century)

By the late 19th century, Mombasa was again up for sale — not literally, but in the quiet bargains struck between empires. The Omani sultans in Zanzibar still claimed the coast, but their grip was weakening. Britain, already planting flags across the globe, was looking hungrily at East Africa’s interior. Mombasa, perched on the ocean and tied into caravan routes, was the key. In 1895, the Sultan of Zanzibar leased the ten-mile coastal strip to the British for a pittance, and Mombasa was folded into the new East Africa Protectorate.

For a brief moment, Mombasa was the colonial capital. British administrators moved into bungalows shaded by palm trees, declaring that the Empire had arrived. But their eyes were already set inland. The Uganda Railway, begun in 1896, turned Mombasa into a launchpad rather than a destination. The iron snake would crawl 900 kilometers from the port, through wilderness and highlands, to Lake Victoria. Nairobi, once a swampy railway depot, would soon eclipse Mombasa as the administrative center.

Still, Mombasa remained the gateway to the colony. Every immigrant laborer from India, every settler from Britain, every bale of cotton or sack of coffee passed through its docks. The port grew into a sprawling industrial zone, with warehouses, cranes, and shipping lines tying Kenya to global trade.

Colonial Mombasa was as segregated as a map. Europeans claimed the breezy neighborhoods, Asians dominated commerce and middle-class housing, and Africans were pushed into cramped quarters around the docks. Old Town remained Swahili and Arab, with its narrow alleys and carved doors, but the colonial city imposed its own order: zoning, passes, and racial hierarchies that decided where one could live, work, or even walk after dark.

But Mombasa was not just a port of goods; it was also a port of ideas. Workers at the docks became some of the most politically conscious laborers in the colony. They struck, organized, and resisted. In 1947, the Mombasa Dockworkers’ Strike erupted — Kenya’s first mass protest movement, paralyzing the colony’s economic lifeline and foreshadowing the labor militancy that would fuel independence.

For the British, Mombasa was a crown jewel of logistics. For Africans, it became a stage of struggle, a place where empire could be resisted by refusing to move its cargo. By the time independence came in 1963, Mombasa had been battered by centuries of foreign flags, yet it remained what it had always been: the indispensable doorway to East Africa.

Resistance and Nationalism

If Nairobi was the political stage of independence, Mombasa was its dockyard chorus — loud, restless, and unafraid of confrontation. The port city was more than just a gateway for goods; it was also the gateway for political ideas. And ideas, once they dock, are harder to unload than cargo.

The dockworkers were at the heart of this ferment. They lived on precarious wages, handled the empire’s lifeline, and knew their leverage. In 1947, they staged a strike that paralyzed the colonial economy. It wasn’t just about pay. It was a collective refusal to bow to a system that had consigned them to the bottom. The strike spread like wildfire across East Africa, unnerving the British and energizing nationalists. What the colonial government saw as labor trouble was in fact an early rehearsal for independence politics.

But resistance in Mombasa was not only about workers. It was also about identity. The Coast had always seen itself as distinct — Swahili, Islamic, maritime — and when independence loomed, many feared being swallowed by the Kikuyu- and Luo-dominated politics of the interior. This birthed the Mwambao movement, which argued that the coastal strip should be autonomous, or even merge with Zanzibar, rather than be absorbed into Kenya. Their slogan — Mwambao wa Pwani Yetu (“The Coast is Ours”) — echoed through meetings and petitions.

Nairobi had no patience for it. For Kenyatta and his allies, an autonomous coast threatened national unity. In 1963, the Sultan of Zanzibar formally ceded sovereignty over the ten-mile coastal strip to Kenya, closing the door on Mwambao. The movement was crushed, but its grievances — land alienation, cultural marginalization, economic neglect — never went away. They would resurface decades later in the Mombasa Republican Council (MRC), which revived the cry that the coast had been betrayed.

Nationalism in Mombasa was therefore double-edged. On one side, the dockworkers, unions, and radicals joined the push for Kenyan independence, tying the city’s fate to the interior. On the other, coastal activists resisted the very idea of being folded into a new Kenya that looked suspiciously like another empire, just painted black, green, and red.

When the flag finally changed in December 1963, Mombasa cheered — but warily. The empire was gone, but the old inequalities remained. The city entered independence with the same contradictions that had defined it for centuries: a hub of wealth that rarely enriched its own people, a cultural capital always negotiating its identity, and a port that carried the burdens of empires it never asked for.

Independence and After (1963–Present)

When the Union Jack came down in 1963, Mombasa stood at the center of Kenya’s new story. It was the gateway to the interior, the point where ships unloaded goods that fed the railway, the factories, and the highlands. For the new nation, Nairobi would be the brain, but Mombasa remained the throat — everything passed through it.

The city retained its cosmopolitan fabric: Swahili, Arabs, Indians, and Africans shared the streets, mosques, temples, and markets. Its taarab music drifted through weddings and nightclubs, its cuisine fused spices from across the Indian Ocean, and its carved wooden doors whispered centuries of Swahili pride. Mombasa embodied the Kenyan coast’s unique identity — Islamic, mercantile, multilingual — yet this was precisely why it often clashed with Nairobi’s centralizing state.

Independence did not erase the grievances that Mwambao had voiced. Land remained a festering wound. Much of the most fertile coastal land had been alienated during colonialism, then transferred into the hands of Kenyan elites, leaving local communities dispossessed. Economic development was uneven: the port boomed, but ordinary coastal residents were locked out of its prosperity. Tourism grew into a global attraction, with Europeans sunning themselves on beaches in Nyali and Diani, but locals often found themselves relegated to menial jobs, watching wealth pass them by.

By the 1990s and 2000s, discontent resurfaced. The Mombasa Republican Council (MRC) revived Mwambao’s old grievance, chanting Pwani si Kenya (“The Coast is not Kenya”). The state cracked down, branding the MRC illegal, just as it had done with the Mwambaoists decades earlier. Meanwhile, the global “War on Terror” brought new securitization: young Muslim men in Mombasa were suddenly under surveillance, accused of ties to al-Shabaab, and subjected to extrajudicial killings. The city became not just a port, but a frontier in Nairobi’s security paranoia.

Yet Mombasa endures. Its port remains Kenya’s lifeline, feeding Uganda, Rwanda, South Sudan, and beyond. Its Swahili culture remains vibrant — in music, poetry, and fashion. Its old town, with its carved balconies and narrow alleys, still smells of spices and sea salt, a living archive of centuries of resilience.

Conclusion: Mombasa the Survivor

Mombasa has been many things: a Swahili city-state, a Portuguese fortress, an Omani outpost, a British colony, a Kenyan port. Each empire left its flag and its scars, but none erased the city. Mombasa has survived bombardment, slavery, segregation, and marginalization. It survives still, defiantly Swahili in a state that often forgets the coast’s history runs deeper than Nairobi’s swamp.

To walk its streets today is to hear whispers of all those centuries at once — the call to prayer from a coral mosque, the clang of cargo being unloaded at Kilindini, the strains of taarab from a wedding hall, the slogans of protesters demanding land and justice. Mombasa is not a relic of empire. It is a city that refuses to sink, no matter how many times the tides of history try to drown it.