On the map, Nanyuki sits neatly astride the equator, but history placed it squarely on another dividing line — between empire and nation, race and belonging, memory and erasure. The equator sign at the edge of town draws tourists to pose for photographs, yet few realize that this flat line of latitude once marked the border of the British Empire’s great social experiment: the dream of a White Highlands built on African soil.

The Frontier of the White Highlands

The story of Nanyuki begins in the aftermath of the First World War. Britain, eager to reward its veterans and consolidate control over central Kenya, opened up tracts of land along the Laikipia plateau to European settlement. The 1920s saw the creation of a small but ambitious settler outpost: Nanyuki, a frontier town at the foot of Mount Kenya, where ex-soldiers, aristocrats, and dreamers came to build a miniature England in the tropics¹.

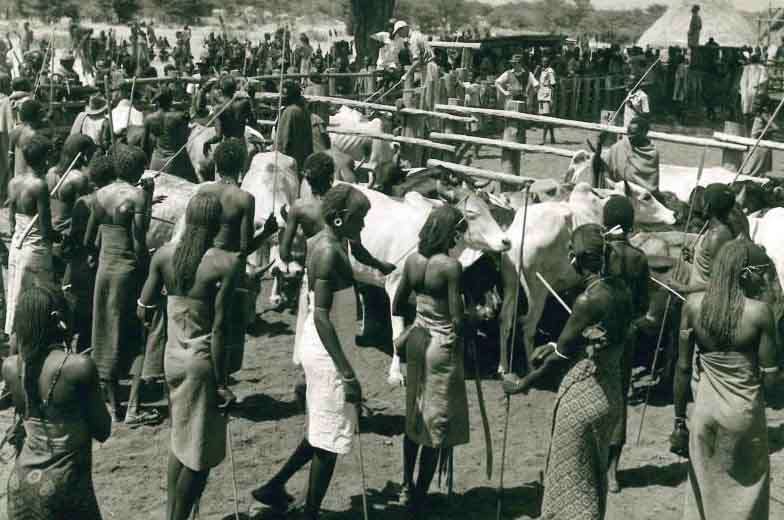

Among the first was Major Charles Paice, whose ranch and personality defined the district for two decades. Paice’s Nanyuki, as historians C. J. D. Duder and C. P. Youé describe, was a world of fences and hierarchies — a community where the frontier spirit of the settlers fused with racial arrogance². The early Europeans carved out vast ranches from land that had long sustained the Mukogodo Maasai, the Kikuyu squatters, and nomadic Samburu herders. Colonial surveys and the Soldier Settlement Scheme formalized these seizures under law, confining Africans to reserves while Europeans occupied the most fertile and temperate lands.

Nanyuki’s early settlers were unlike the plantation magnates of the Rift Valley. They were smaller men, former officers and tradesmen seeking self-sufficiency far from Nairobi’s bureaucracy. They built a town of timber shacks, dusty tracks, and tin-roofed shops. In the evenings, they gathered at Paice’s home or the settlers’ club to drink, gamble, and trade gossip about labor, land, and the threat of African agitation. Beneath their camaraderie ran a vein of fear — of encroachment, of change, and of the Africans whose labor they could not live without.

A Town Governed by Whiteness

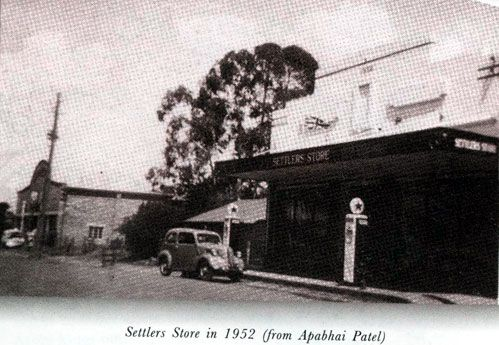

By the late 1920s, Nanyuki had developed into what Duder and Youé call a “settler fiefdom,” where social life revolved around whiteness itself². The district administration, police, and courts were designed to preserve European supremacy. Africans worked the ranches under harsh conditions and faced curfews and pass laws. Asians, who arrived as shopkeepers and artisans, were tolerated but kept at a distance.

Paice’s authority extended beyond his property. He served on local committees, mediated disputes, and maintained close ties with Nairobi’s colonial elite. His district became a model for the segregationist ideology that underpinned the White Highlands — the belief that Kenya’s high country was destined for European civilization while Africans belonged in the reserves. Paice and his contemporaries viewed Nanyuki as a frontier buffer protecting the colony from what they called “the native flood.”

Yet isolation bred paranoia. The Great Depression struck the settlers hard, reducing profits from wool and cattle. Many farms failed, and a few turned to poaching or smuggling to survive. Meanwhile, African laborers began to organize informally, demanding better wages and resisting forced evictions. Beneath the calm surface of settler order, cracks were forming.

War and the Military Frontier

The Second World War transformed Nanyuki’s fortunes. Its position on the Laikipia plateau — high, flat, and strategic — made it ideal for a Royal Air Force base. The town became a logistical hub for Allied operations in East Africa. Airstrips were built; roads improved; and the population swelled as African porters, mechanics, and clerks poured in to serve the war effort. For a brief moment, Nanyuki felt central to the empire’s survival.

After the war, the returning veterans reinforced the settler population. The 1950s brought a different kind of conflict: the Mau Mau uprising. Nanyuki’s ranches, bordering the forested slopes of Mount Kenya, became militarized zones. The town served as a supply depot and intelligence center for colonial forces. African detainees from nearby villages were rounded up and confined in camps or forced into labor gangs. What began as a frontier dream ended as a fortified garrison.

Independence and the Survival of the Frontier

When Kenya gained independence in 1963, Nanyuki was still unmistakably colonial. Many settlers sold their land and left, but others stayed — drawn by the landscape or protected by quiet deals with the new government. The British military presence, formalized through bilateral agreements, ensured that the town retained its old rhythm of uniforms, drills, and parades. The British Army Training Unit Kenya (BATUK), stationed just outside town, became one of the largest foreign military facilities in East Africa. Its soldiers continued to march through streets once patrolled by their colonial predecessors.

For ordinary Kenyans, independence did not immediately translate into land ownership or opportunity. The large ranches were bought by new elites or foreign investors, while smallholders settled on marginal plots along the town’s edge. Still, Nanyuki began to change. The once-white trading center grew into a cosmopolitan town of Africans, Asians, and Europeans living side by side — though rarely as equals.

From Garrison to Gateway

By the 1980s and 1990s, Nanyuki had shed much of its isolation. The opening of Mount Kenya National Park and the rise of private conservancies such as Ol Pejeta turned the district into a magnet for tourism and conservation funding. The same ranches that had once excluded Africans reinvented themselves as eco-lodges and wildlife sanctuaries. British soldiers trained on the plains where Maasai herders still grazed their cattle, creating a landscape of uneasy coexistence.

The town’s economy boomed. New hotels, schools, and residential estates rose along the highway. Yet beneath the progress, the colonial legacy endured. Land ownership remained concentrated in a few hands, and periodic tensions erupted between pastoralists and ranchers. When droughts struck, herders pushed their cattle into private conservancies — a stark reminder that the old boundaries of privilege had never truly disappeared.

The Equator’s Shadow

Today, Nanyuki stands as both a relic and a reinvention. The main street hums with cafés, safari trucks, and soldiers in fatigues. Young Kenyans come seeking work or adventure, while expatriates treat it as a highland retreat. At night, the lights of the army camp glow across the plains, just as they did in Paice’s time.

The equator sign remains the town’s most photographed landmark — a tourist novelty that conceals deeper meaning. It is the perfect metaphor for Nanyuki: a place defined by balance and division, forever poised between two worlds. The empire may have fallen, but its lines endure, etched into the land, the economy, and the quiet power of memory.

Legacy

Nanyuki’s story is not just about settlers or soldiers; it is about the persistence of colonial geography in the life of a post-colonial nation. From Paice’s ranch to BATUK’s barracks, the town has been shaped by those who came seeking control over land and space. Yet it has also been remade by those who refused to leave — the traders, herders, and families who turned a garrison into a home.

A century after its founding, Nanyuki remains Kenya’s equator town, where the ghosts of empire still walk the streets but no longer dictate the future. In that sense, the equator line running through its heart is not just a geographical curiosity — it is a scar, a reminder, and perhaps a line of hope that one day, balance will mean something more than separation.

References

¹ Duder, C. J. D., & Youé, C. P. (1994). Paice’s Place: Race and Politics in Nanyuki District, Kenya, in the 1920s. African Affairs, 93(370), 253–276.

² Ibid., pp. 256–259.