For most of the twentieth century, nearly half of Kenya’s land area existed outside the national imagination. The Northern Frontier District (NFD) — stretching from the Tana River to the Ethiopian border — was a vast, semi-arid expanse of deserts, plateaus, and seasonal rivers. Populated by nomadic pastoralists such as the Somali, Borana, Rendille, Samburu, Turkana, and Gabra, the region became both a geographic and political frontier. Created by the British in 1909, the NFD was administered not as part of Kenya proper but as a separate security zone.

This isolation shaped everything that followed. The NFD became a space of marginalization, rebellion, and resilience — a landscape where colonial boundaries collided with ancient cultures of mobility.

1. Ancient Networks and Precolonial Frontiers

Archaeological and ethnographic research reveals that what later became the Northern Frontier District was not an empty wasteland but a densely networked cultural landscape. Human occupation in northern Kenya stretches back thousands of years, with evidence of both hunter-gatherer and pastoralist societies. Excavations by A. T. Curle (1933) in Wajir, Mandera, and the Chalbi Basin uncovered prehistoric graves, pottery, and beadwork that point to a sophisticated material culture and long-term trade connections with the Ethiopian and Somali highlands. These findings show that mobility was not a mark of primitiveness but a deliberate ecological adaptation to an unpredictable environment.

The region’s communities developed intricate systems for managing movement, grazing, and kinship. According to Oba (2013), the rangelands that stretch from the Borana Plateau in southern Ethiopia to the Kaisut and Dida Galgalu deserts in Kenya functioned as ecological corridors—shared landscapes where clans and lineages negotiated access based on rainfall and seasonal cycles. Livestock herding was both an economic and social practice. Camels, cattle, and goats were exchanged through dowry, alliance, and restitution, reinforcing bonds across vast territories.

Frontiers, in the precolonial sense, were porous rather than partitioned. Movement followed logic, not law. Borana, Rendille, Gabra, and Somali clans maintained cross-border grazing agreements known as dedha or xeer, where elders met at wells to coordinate resource sharing and resolve disputes. Oba describes this system as a form of “mobile sovereignty” — authority tied to people and herds rather than fixed ground. Elders and religious leaders ensured peace through oath rituals, and conflict, when it occurred, was mitigated through compensatory mechanisms like mag (blood wealth) or livestock fines.

Trade routes reinforced this connectivity. From as early as the fifteenth century, camel caravans linked Lake Turkana, Marsabit, and Moyale to markets in Harar, Berbera, and Lamu. These routes carried salt, ivory, and hides northwards, and beads, metalwork, and cloth southwards. Anthropological studies note that some of these paths later formed the basis of colonial “caravan roads.” Long before formal states emerged, the people of northern Kenya maintained what Oba (2013) calls “social landscapes of exchange”—a web of reciprocal relations that transcended ethnicity and territory.

Spiritual life was equally intertwined with geography. Many communities viewed wells, hills, and acacia groves as sacred sites, inhabited by ancestral spirits or guarded by divine taboos. Seasonal rituals, often tied to rainfall and fertility, ensured harmony between people and land. The Borana’s gadaa system, for example, organized time into eight-year cycles of leadership renewal, reflecting a cosmology of balance between humans, nature, and the divine.

In this context, the very notion of a fixed frontier—a line dividing one authority from another—was alien. For pastoral societies, space was relational, not territorial. Identity was tied to lineage and movement rather than a static homeland. Rainfall determined where people lived; kinship determined where they belonged. The boundaries of the precolonial north were therefore dynamic zones of interaction, not barriers of exclusion.

When colonial officials later imposed rigid borders between Kenya, Ethiopia, and Somalia, they cut across this living web of relationships. What had been a flexible, negotiated frontier became an instrument of surveillance and separation. As Oba (2013) notes, “colonial boundary-making did not create order; it dismantled a pastoral logic that had sustained peace for centuries” (p. 18).

2. Creating the Colonial Frontier (1909–1940s)

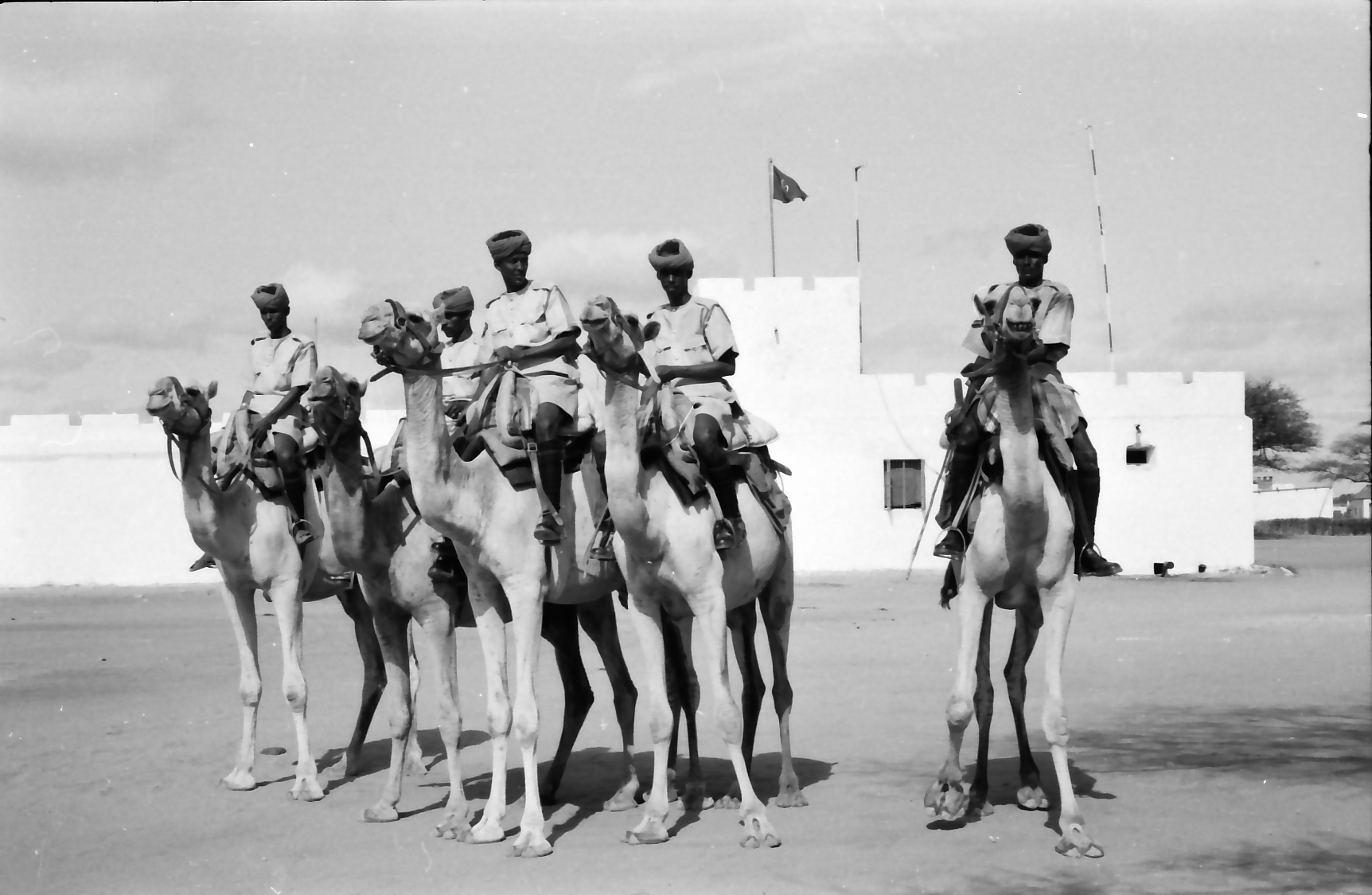

The British established the Northern Frontier District in 1909 as a buffer zone between their East African territories and Italian Somaliland. According to Parkinson (1932), the district was placed under direct provincial administration, separate from the “Settled Areas” of central Kenya. Officials ruled through military patrols and a handful of district commissioners based in Isiolo, Marsabit, and Wajir.

The colonial government justified this isolation under the Closed Districts Ordinance of 1926, which required entry permits for both Africans and Europeans. The aim was not integration but containment. McKay (1940) observed that the administration treated the NFD as a quarantine zone for disease and unrest — restricting livestock movement under the guise of veterinary control while maintaining surveillance over “unruly tribes.”

Education and infrastructure were minimal. Missionaries were limited to a few outposts; schools were virtually absent. Lewis (1963) later described the NFD as “an internal colony,” governed through police, intelligence, and minimal development investment (p. 41).

3. Ecology of Control and the Politics of Pastoralism

Colonial policy in the NFD revolved around livestock and mobility. McKay (1940) noted that veterinary regulation — vaccination drives, quarantine lines, and forced destocking — doubled as political control. By monitoring animal movement, administrators controlled people.

Holtzman (2005) terms this “governing through the herd,” where pastoral wealth became the lever of obedience. The British introduced grazing schemes that restricted movement and enforced hierarchical chieftaincy among decentralized pastoral groups. These interventions disrupted indigenous coping mechanisms for drought and fostered competition over scarce pasture.

Oba (2013) argues that colonial resource capture created the foundations of modern conflict: when drought struck, those confined to smaller reserves faced starvation or raids. Frontier administration thus turned ecology into a system of discipline.

4. Identity and Partition: Between Somalia, Ethiopia, and Kenya

The northern frontier was never just a Kenyan problem — it was part of a larger colonial jigsaw. Between 1897 and 1914, European powers drew the Anglo-Ethiopian and Anglo-Italian boundaries with little regard for cultural continuity. Lewis (1963) points out that these artificial lines divided clans whose economic and social lives depended on seasonal migration.

As Somali nationalism grew after World War II, the NFD’s population began to identify with a greater Somali homeland. The British themselves encouraged this sentiment for strategic reasons: they proposed, but never realized, a union of northern Kenya and British Somaliland under a single administration. When decolonization approached in the 1950s, Britain reversed this stance, deciding to retain the NFD within Kenya.

The Northern Frontier Commission (1962) revealed the depth of discontent. More than 80% of respondents declared their desire to join Somalia, citing shared language and religion (Lewis, 1963, p. 47). But at the Lancaster House Conference of 1963, the British confirmed the colonial borders as permanent, disregarding the plebiscite results.

5. The Shifta War (1963–1967)

Independence brought new conflict. When Kenya gained sovereignty in December 1963, Somali leaders in the north rejected inclusion in the new state and launched an armed insurgency known as the Shifta War (“Shifta” meaning bandit).

Lewis (1963) and Kassam (2015) note that the rebellion was driven less by criminality than by self-determination. Fighters sought either union with Somalia or regional autonomy. In response, President Jomo Kenyatta’s government declared a State of Emergency in the NFD, deploying the army and enforcing strict curfews.

Villagers were relocated into fortified settlements — a system eerily similar to the Mau Mau “protected villages” of the 1950s. Oba (2013) records that entire herds were confiscated, and grazing routes closed. Thousands died from hunger or violence. The war officially ended in 1967, but mistrust between the region and the central government persisted for decades.

6. Post-War Marginalization and Frontier Development

After the Shifta War, the NFD remained under heavy security surveillance. Development projects were introduced through the Frontier Counties Development Programme of the 1970s, but these were limited to roads and boreholes. Mosley and Watson (2016) observe that while the rest of Kenya urbanized, the north was treated as a “zone of exception” — a place of humanitarian aid rather than investment.

Holtzman’s (2004) ethnography in Samburu illustrates the everyday consequences: chiefs gained power as intermediaries between government and communities, but real local autonomy was absent. Cultural change came unevenly, with education and medical access still far behind the national average.

Yet, the frontier also fostered creativity and adaptation. Islamic education thrived in Wajir and Mandera; mobile veterinary services and peace committees emerged as grassroots responses to neglect.

7. Frontier Towns and Changing Spaces

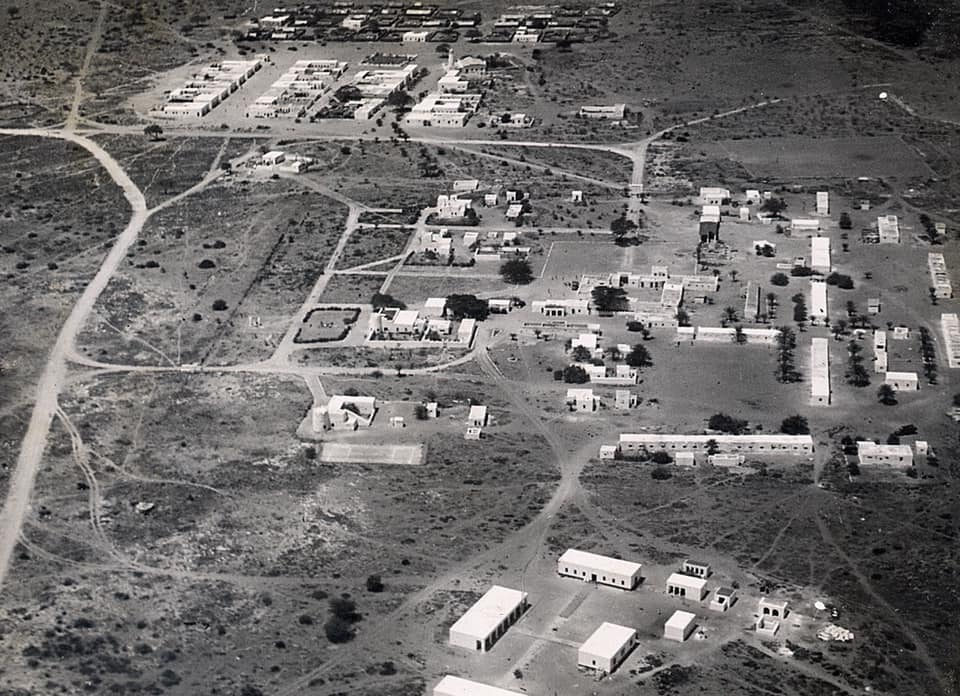

Despite historical isolation, several towns in the north grew out of colonial outposts. Waweru (2012) documents how Maralal, Marsabit, and Isiolo expanded from military posts into trade centers between 1909 and 1940. Their growth reflected a gradual shift from surveillance to settlement.

By the late twentieth century, Isiolo became a major crossroads linking central Kenya to Ethiopia and Somalia. Mosley and Watson (2016) show that new “frontier urbanization” followed development corridors such as the Lamu Port–South Sudan–Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) project. The frontier that once represented exclusion is now marketed as Kenya’s “new economic frontier.”

However, infrastructure alone cannot erase historical inequalities. As Oba (2013) warns, sustainable development in the north must recognize its distinct ecology and pastoral traditions rather than impose sedentary models imported from the south.

8. Cultural Resilience and Identity

Despite a century of political neglect, the peoples of the NFD have preserved rich cultural traditions. Pastoral rituals, clan law (xeer among Somalis), and respect for elders remain vital. Holtzman (2005) describes how Samburu elders use oral histories to teach moral order, while Borana and Rendille communities maintain customary peace pacts known as gadaa.

Religious and linguistic unity — especially the spread of Islam and Swahili — now connects towns across the frontier. Radio stations in Garissa and Wajir broadcast in Somali and Swahili, linking communities once divided by distance. Schools and county governments have also helped redefine citizenship, making participation in the Kenyan state less abstract than it was in the colonial era.

Culturally, the frontier remains a bridge between Kenya and the Horn of Africa. Its music, dress, and storytelling blend Cushitic, Nilotic, and Bantu influences — a living record of movement and exchange.

9. Devolution and the Reimagining of the North (2010–Present)

The 2010 Constitution introduced county governments that transformed the political geography of the former NFD. Counties such as Garissa, Mandera, Marsabit, Isiolo, and Wajir gained elected leadership and greater control over budgets. Mosley and Watson (2016) note that devolution sparked a new sense of belonging, as local voices began shaping priorities.

Today, the frontier hosts major infrastructure projects — highways, oil exploration, and cross-border trade hubs — yet challenges remain. Recurrent droughts, insecurity, and clan competition persist. Nonetheless, the narrative is changing: what was once the “periphery” is now central to Kenya’s connection with Ethiopia and Somalia.

Conclusion

The story of the Northern Frontier District reveals how borders create not only divisions but also enduring identities. From colonial isolation to postcolonial neglect, the NFD has remained a testing ground for Kenya’s ideas of citizenship and inclusion.

Archaeological continuity shows the region’s deep past; colonial archives expose its bureaucratic marginalization; and modern ethnography highlights its resilience. The frontier is no longer a blank space on the map. It is a living region where cultures adapt, resist, and redefine what it means to be Kenyan.

Understanding the NFD is essential to understanding Kenya itself — a nation forever negotiating between its center and its edges, between control and culture.

References

Curle, A. T. (1933). Prehistoric graves in the Northern Frontier Province of Kenya Colony. Nairobi: British Museum Archives.

Holtzman, J. D. (2004). The local in the local: Models of time and space in Samburu District, Northern Kenya. American Ethnologist, 31(1), 107–123.

Holtzman, J. D. (2005). The drunken chief: Alcohol, power, and the birth of the state in Samburu District, Northern Kenya. American Ethnologist, 32(1), 120–138.

Kassam, A. (2015). Review of Gufu Oba, “Nomads in the Shadows of Empires.” Horn of Africa Review, 12(3), 88–94.

Lewis, I. M. (1963). The problem of the Northern Frontier District of Kenya. The Journal of Modern African Studies, 1(3), 239–256.

McKay, W. M. (1940). Some problems of colonial animal husbandry, Part I: The Northern Frontier Province of Kenya. East African Agricultural Journal, 6(2), 77–85.

Mosley, J., & Watson, E. (2016). Frontier transformations: Development visions, spaces and processes in Northern Kenya and Southern Ethiopia. Journal of Eastern African Studies, 10(3), 452–471.

Oba, G. (2013). Colonial resource capture: Triggers of ethnic conflicts in the Northern Frontier District of Kenya, 1903–1930s. Pastoralism, 3(2), 1–15.

Parkinson, J. (1932). Notes on the Northern Frontier Province, Kenya. Nairobi: Government Printer.

Waweru, P. (2012). Frontier urbanisation: The rise and development of towns in Samburu District, Kenya, 1909–1940. Nairobi: University of Nairobi Press.