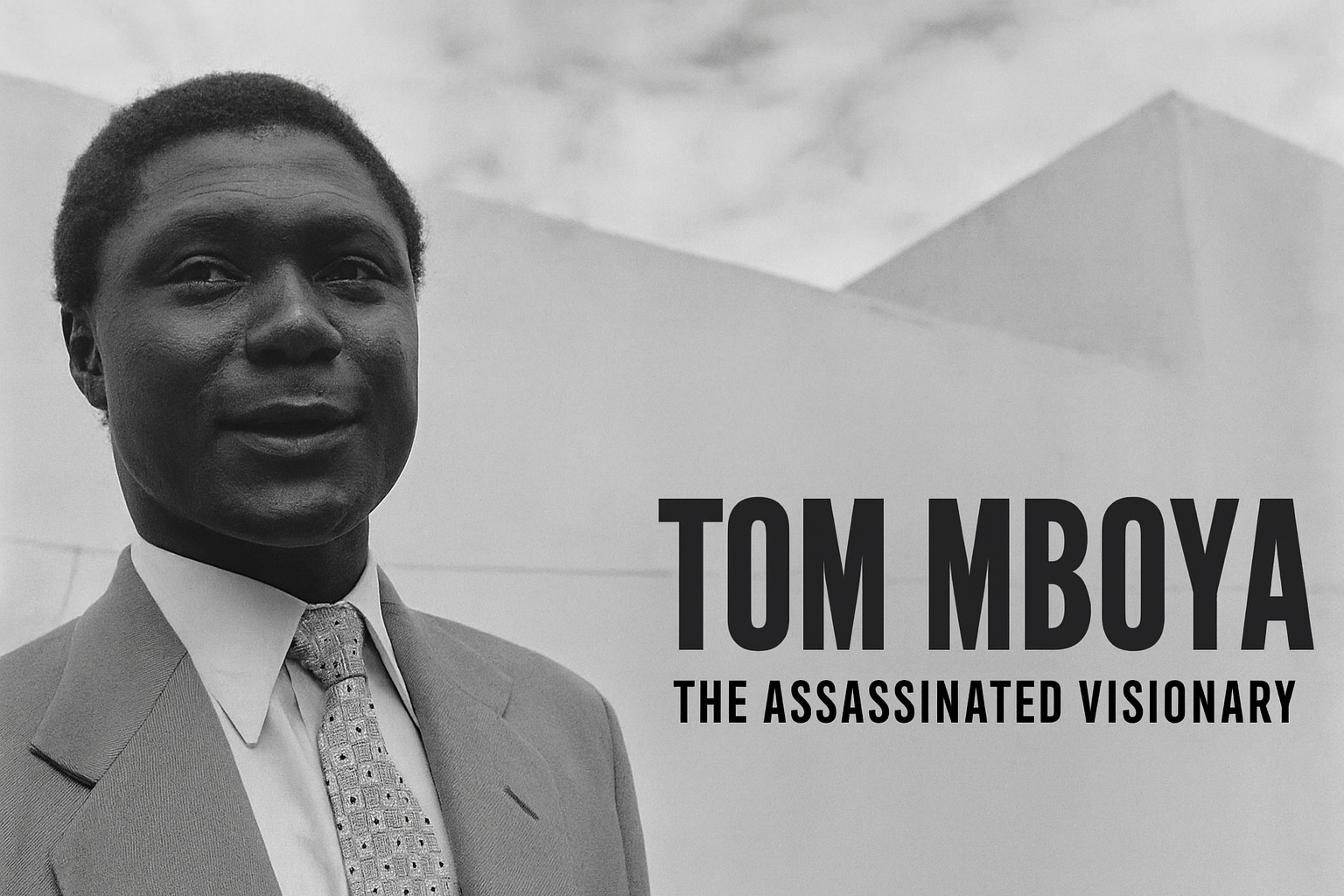

On the afternoon of July 5, 1969, Tom Joseph Mboya stepped out of Chhani’s Pharmacy on Government Road, Nairobi. He had just bought a bottle of lotion. As he walked to his car, a man approached, pulled a revolver, and fired. Mboya collapsed on the pavement, bleeding out at just 39 years old. By the time he reached Nairobi Hospital, he was gone.

A Shot on Government Road

News of his assassination ripped through Kenya. Crowds poured into the streets; wails echoed from Nairobi to Kisumu. In that single shot, Kenya lost not just a minister but the brightest star of its independence generation. Tom Mboya was more than a politician. He was an architect of the nation, a man who could quote Shakespeare in one breath and draft five-year plans in the next. His death was not just murder. It was betrayal — the silencing of a vision too sharp for its time.

From Rusinga to Nairobi

Mboya was born in 1930 on Rusinga Island, in Lake Victoria, to a Luo family of modest means. His childhood was stitched with the rhythms of fishing and farming, but also with the hunger of a people excluded from the settler economy. Like many bright Luo boys, he entered the mission school system, excelling first at St. Mary’s in Yala, then at Holy Ghost College, Mangu.

Unlike many of his peers, he did not drift into teaching or clerical work. He trained as a sanitary inspector — a job that, while humble, gave him authority in Nairobi’s estates and exposed him to the struggles of urban Africans. In the slums and factories, he saw the machinery of colonial inequality up close. It was there, among laborers and street hawkers, that he found his political voice.

The Trade Unionist

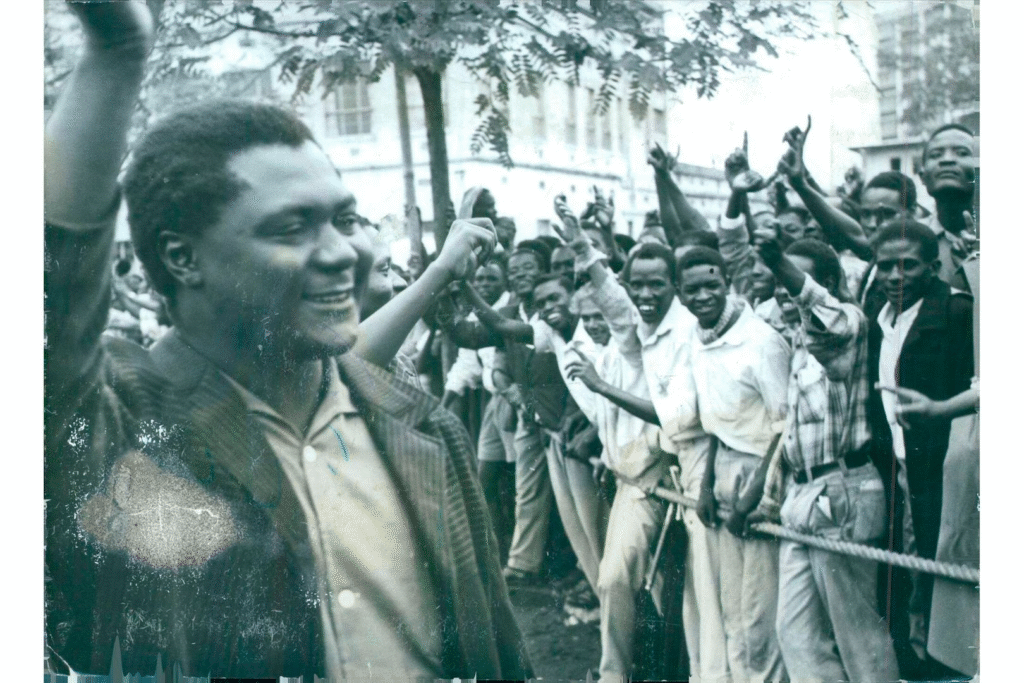

The 1950s were years of fire. The Mau Mau war raged in the forests, Kikuyu reserves bled under collective punishment, and Nairobi’s streets bristled with unrest. Into this storm stepped Mboya, young, articulate, and fearless.

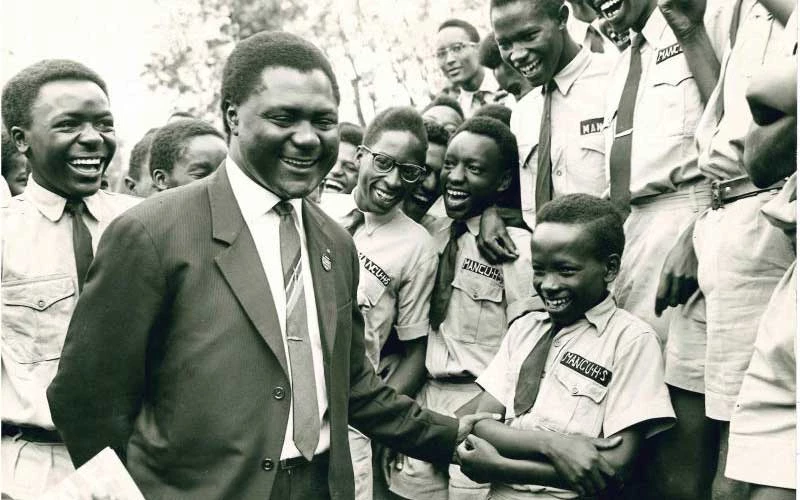

In 1953, at just 23, he was elected Secretary-General of the Kenya Local Government Workers Union. Within two years, he had risen to head the Kenya Federation of Labour, becoming the most powerful African trade unionist in the colony. His talent was not just organization but articulation. He could speak to workers in Kiswahili in the morning and address international conferences in London or New York in polished English by evening.

Mboya understood that labor was not just about wages — it was about freedom. He linked workers’ struggles to the larger fight against colonial rule. And unlike many nationalist leaders restricted to the colony, he built international networks, securing scholarships, funding, and attention for Kenya’s cause abroad.

The Political Star

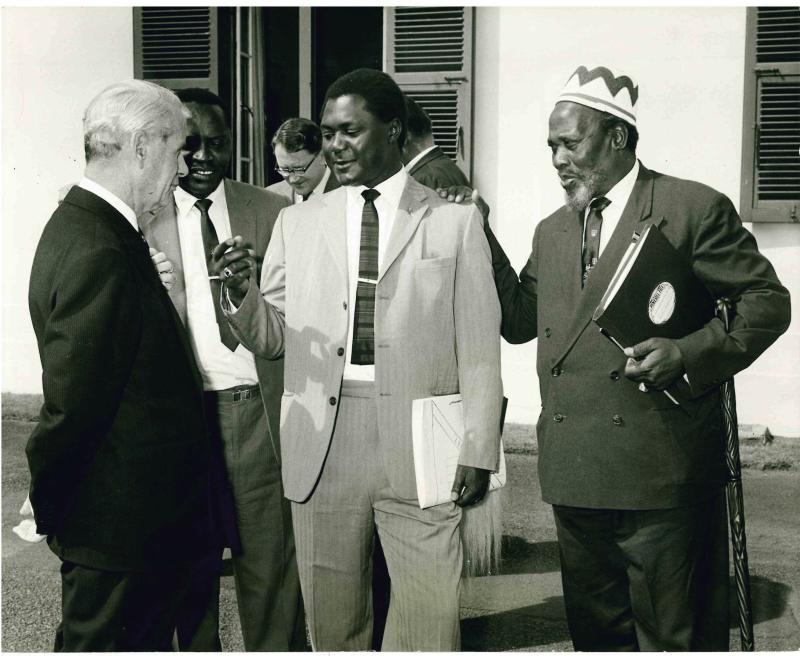

When nationalist politics began to organize formally, Mboya was already indispensable. He was central to the founding of the Kenya African National Union (KANU) in 1960, alongside Jomo Kenyatta, Oginga Odinga, and others. While Kenyatta was still in detention, Mboya carried the nationalist banner abroad, attending the Lancaster House Conferences in London that hammered out Kenya’s independence constitution.

He was charismatic, modern, and pragmatic. While others were still locked in ethnic rivalries, Mboya spoke the language of nationalism. While Mau Mau had been crushed militarily, Mboya was fighting a different war: the diplomatic and intellectual battle to prove Kenya was ready for self-rule.

The West noticed. During the Cold War, he became Washington’s favored son in East Africa — articulate, anti-communist, and polished. It was under his guidance that the Kennedy Airlift of 1959–63 took hundreds of young Kenyans and East Africans to American universities, including a young Barack Obama Sr. Mboya understood that the future was not just independence but education. Kenya needed technocrats as much as it needed freedom fighters.

The Visionary Minister

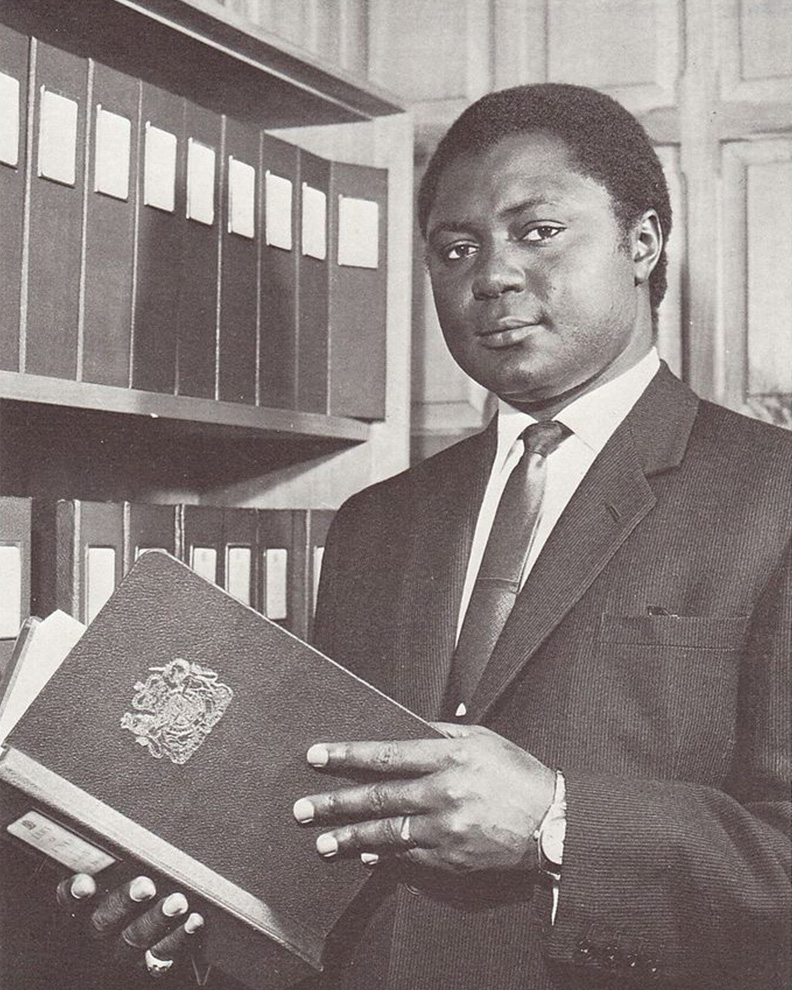

At independence in 1963, Mboya was appointed Minister of Labour, and soon after, Minister for Economic Planning and Development. Here, his vision took flight. He was the architect of Sessional Paper No. 10 of 1965, a blueprint for “African Socialism and Development.” It laid out Kenya’s economic path: a mixed economy with both private investment and state control, designed to balance growth with equity.

He was barely in his thirties, yet his fingerprints were everywhere: on industrial policy, on education reform, on the building of a new bureaucracy. He was young, but he was not naïve. He knew Kenya was entering a treacherous era where independence leaders would be forced to choose between ideals and power.

To many, Mboya was Kenyatta’s heir apparent — a Luo leader who could bridge ethnic divides, a modernist who could appeal to both peasants and the West. That made him both indispensable and dangerous.

The Bullet

On July 5, 1969, as Mboya lay dying on Nairobi’s tarmac, Kenya changed forever. His assassin, Nahashon Njenga Njoroge, was quickly arrested and tried. But suspicion spread faster than the courts could handle. Njoroge’s chilling words at his trial — “Why don’t you ask the big man?” — fed whispers that Mboya had been eliminated by forces larger than one man with a gun.

For Luo communities, his death was a rupture. Kisumu, already tense after Tom’s rivalry with Kenyatta’s Kikuyu elite, erupted in fury. When Kenyatta visited the city later that year, the anger boiled over into the Kisumu Massacre, where police opened fire on protesters. Mboya’s ghost became part of a wider wound — of betrayal, marginalization, and blood.

Legacy

Mboya left behind more than a ministry. He left a void. His brilliance as an orator, his pragmatism as a planner, and his charisma as a nationalist made him irreplaceable. In death, he became the president Kenya never had, the visionary silenced before his time.

Monuments were erected — a statue on Moi Avenue marks the spot where he fell, his face cast in bronze, forever young. Books and biographies have tried to capture him, but his true legacy is scattered: in the universities filled with graduates from the Airlift, in the policies that shaped Kenya’s early economy, and in the unhealed suspicions of his murder.

For the Luo, he remains a martyr; for Kenya, he remains a symbol of potential unrealized. His death foreshadowed a pattern in Kenyan politics: bright stars cut down, ideals betrayed, promises deferred.

Kenya’s Lost President

If Dedan Kimathi was the lion of the forest and Wangari Maathai the mother of trees, then Tom Mboya was the architect of modern Kenya — the visionary who built the scaffolding of independence. His assassination was not just a personal tragedy but a national one, a reminder that Kenya’s path would be as much about betrayal as about freedom.

The shot on Government Road still echoes. Every time Kenyans speak of lost opportunities, of leaders betrayed, of justice deferred, Mboya’s name hovers in the air. He was not just killed. He was stolen.

And Kenya has never stopped counting the cost