A Visual History of Power, Propaganda, Protest, and Everyday Survival

1978 – The End of One Era, the Beginning of Another

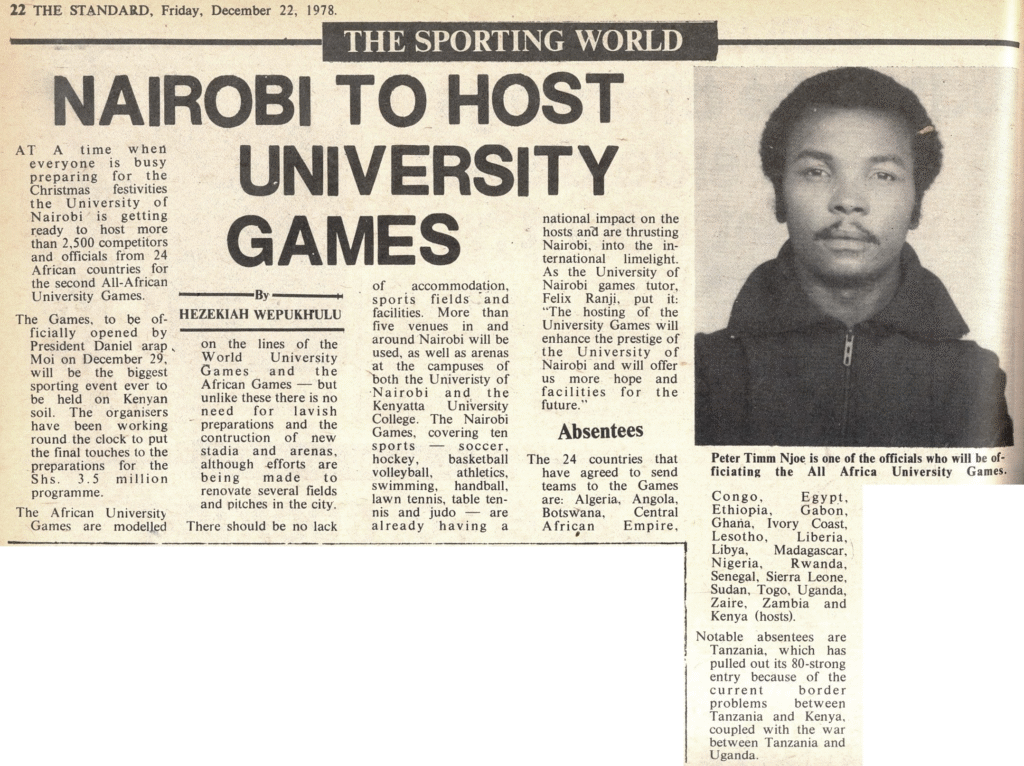

Nairobi entered 1978 in mourning. Jomo Kenyatta’s death triggered a carefully orchestrated state funeral that drew presidents, princes, soldiers, and crowds that stretched across the city. The ceremony was as much about grief as it was about continuity. Daniel arap Moi, the quiet vice-president who had survived years of hostility from the Kiambu elite, took the oath of office and inherited a Nairobi still shaped by colonial geography but already expanding into a regional hub.

Aerial photos from the year show a compact, orderly city clustered around Parliament Road, the Hilton, and the then-new Uhuru Highway—symbols of an economy still buoyant, a police state still soft, and a political transition that appeared calm on the surface.

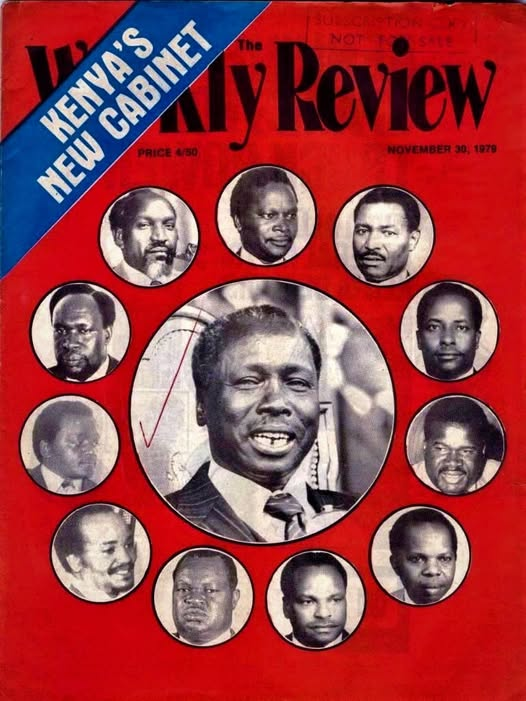

1979 – A City Learning Its New Master

The first full year of Nyayo rule left Nairobi largely unchanged in appearance, but the mood had shifted. Street scenes around Barclays Bank, Dames Outfitters, and the busy intersections near the National Archives show a capital still leaning on structures and rhythms established in the 1960s. But the politics had begun to harden. The one-party state tightened its grip while the city’s population grew faster than infrastructure.

The photographs from 1979 reveal the last moments before the explosive expansion of the 1980s: modest traffic, structured matatus, clean pavements, and a Nairobi that was still small enough to understand itself.

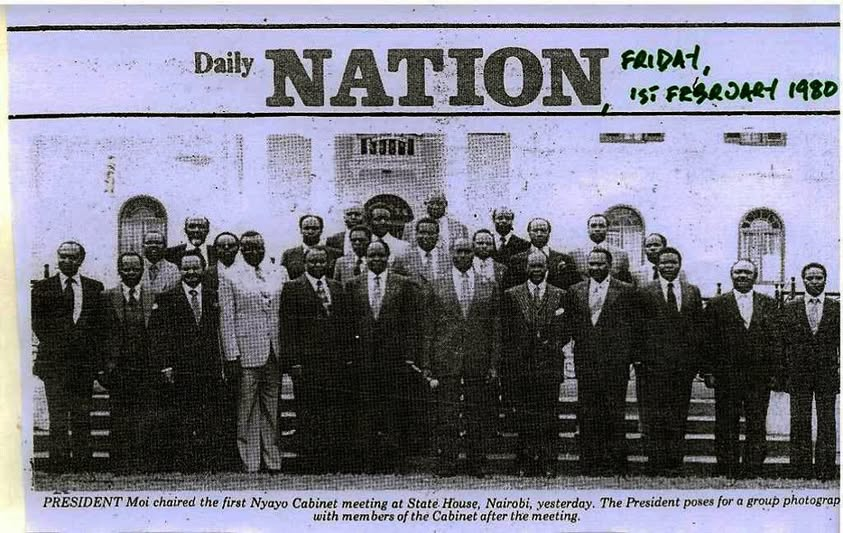

1980 – Shock, Ceremony, and the Edges of Violence

1980 was a year of spectacle and shock. Pope John Paul II’s historic visit filled Nairobi’s streets with singing crowds and rare optimism. Shortly after, the Norfolk Hotel bombing jolted the city into a new awareness of global terrorism. Images of Moi inspecting the ruins show the administration confronting a threat it barely understood.

Beyond crisis, Nairobi’s cultural life thrived. The Kenya rugby team, heavily drawn from Lenana and Nairobi School, embodied the city’s attachment to sport. In the photographs, the 1980s feel young, energetic, and oblivious to the political storms ahead.

1981 – Nairobi in Motion

Surviving footage from 1981 captures the city’s unhurried rhythm before the coming decade reshaped it. Workers crossing Kenyatta Avenue, Kenya Bus Service vehicles moving through the CBD, and the unmistakable KICC tower above a skyline still modest and structured.

It is Nairobi as it was before the coup attempt, before mass layoffs, before the state began policing thought. The calm before the Nyayo engine tightened.

1982 – The Year Everything Cracked

1982 was the year Nairobi woke up to the sound of a revolution that almost—but not quite—took hold. The August 1 coup attempt fractured the city: some hid behind locked doors while others stepped outside to watch soldiers sprint through the streets, smoke rise over Eastleigh, and gunfire echo around the CBD. The aftermath reshaped the Nyayo state. Curfews tightened, detentions multiplied, universities were purged, civil servants were vetted, and entire neighbourhoods fell under closer surveillance.

And for readers with strong hearts, Nairobi’s most turbulent morning is laid bare in our 30-image exposé of the failed 1982 coup, a raw record of a revolution that left the country with the half-taste of what might have been.

1983 – Ceremony on Top, Pressure Below

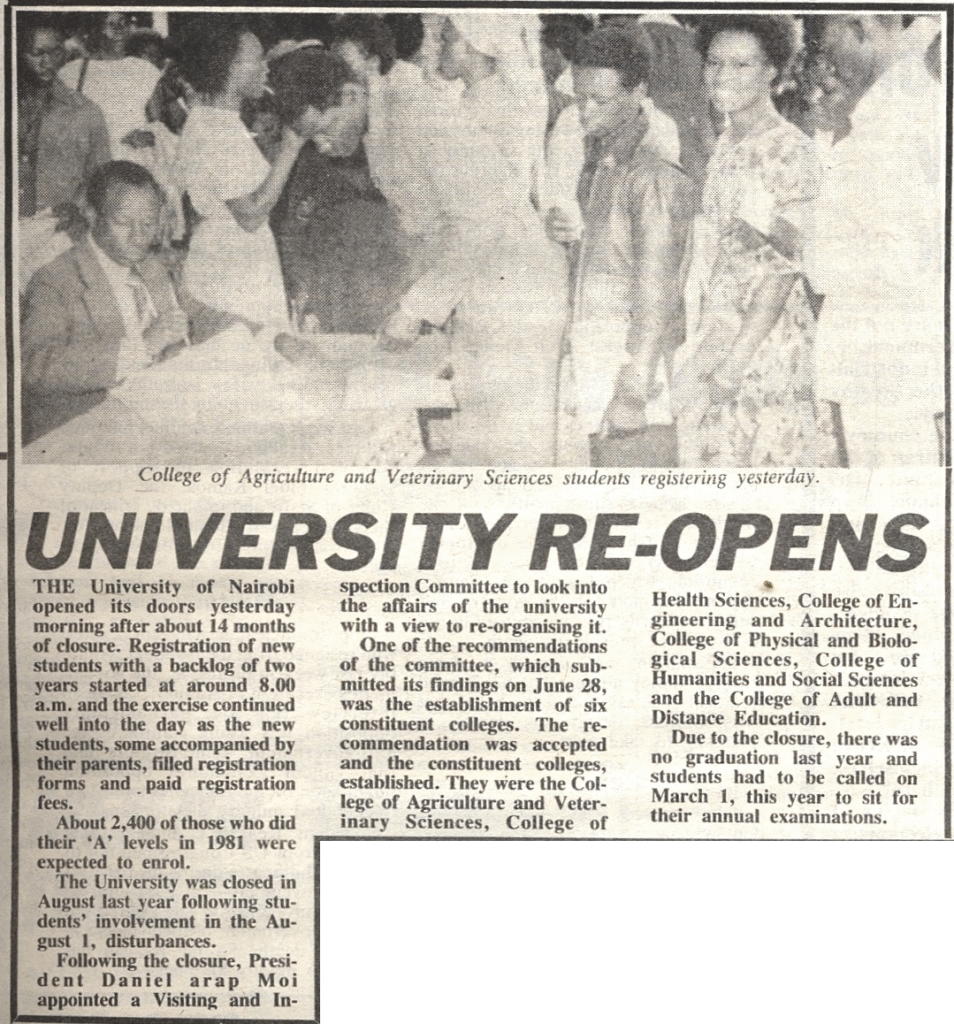

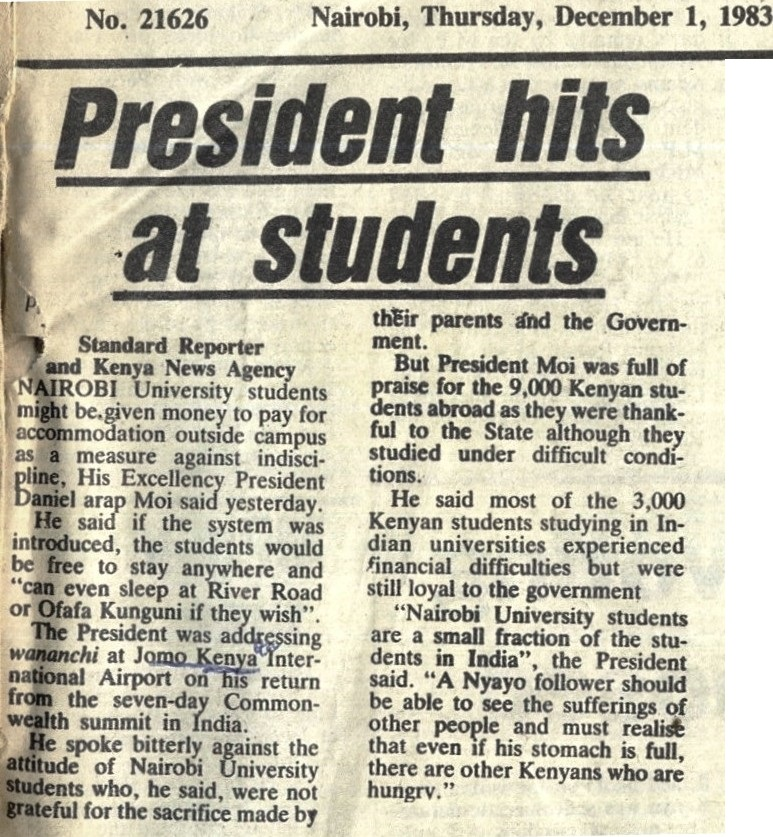

By 1983, Nairobi was split between public pageantry and quiet repression. Queen Elizabeth II’s state visit reminded the world of Kenya’s Commonwealth loyalties even as the government intensified its surveillance of students and intellectuals.

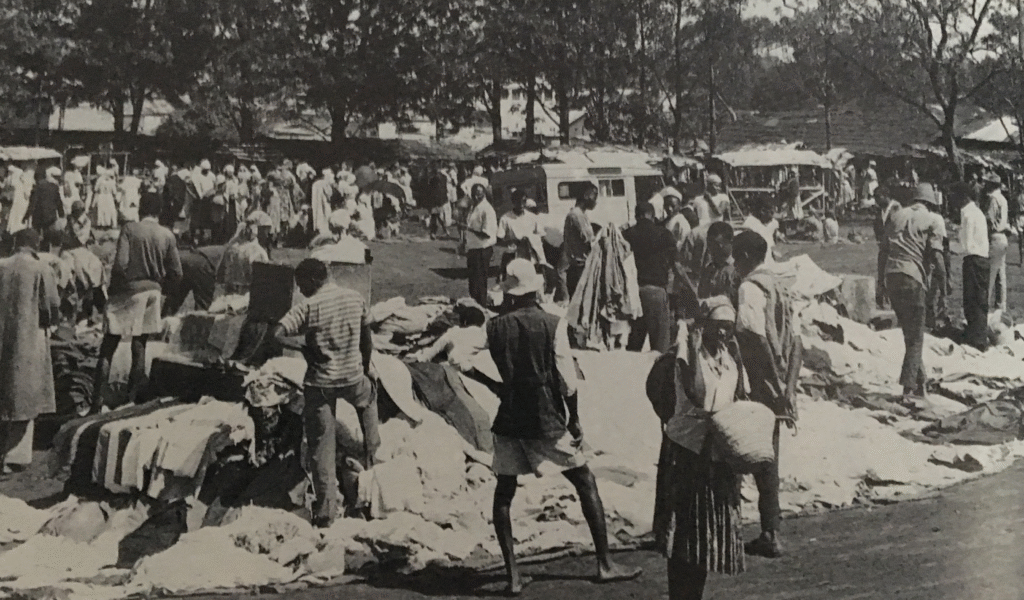

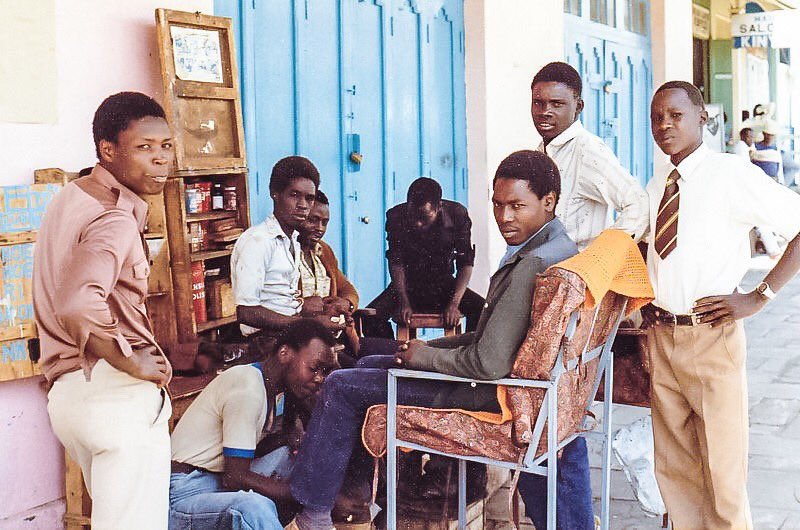

Market scenes from the year show a Nairobi built on informal trade—street vendors outside cinemas, second-hand sellers around Gikomba, and the visible return of campus life after the University of Nairobi reopened following its long shutdown.

Meanwhile, the Safari Rally roared through the country, pulling Nairobi crowds into the spectacle and offering an escape from political anxiety.

1984 – A City Expanding Without a Plan

Images from 1984 capture Nairobi’s steady physical growth alongside deepening inequality. Street corners lined with tailoring shops, buses cutting through ageing residential blocks, and traders negotiating prices in crowded open spaces show a capital expanding faster than its services.

Kawangware, Kibera, and Mathare grew sharply during this period, absorbing workers priced out of the formal city. The slums became a permanent feature of Nairobi’s geography, even as official attention remained elsewhere.

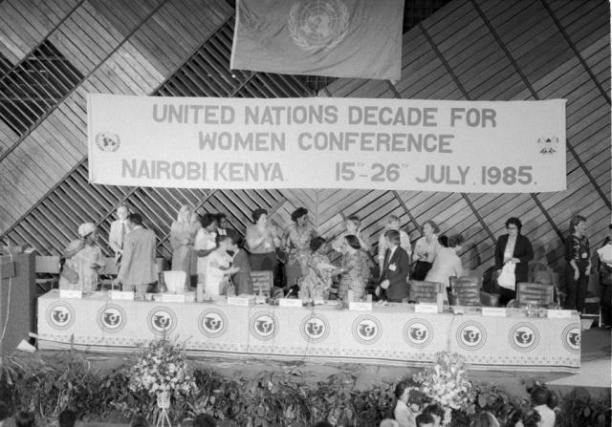

1985 – Activism, Conferences, and Rising Tensions

1985 brought the UN World Conference marking the end of the Decade for Women to Nairobi, turning KICC into a global stage. Delegates filled hotels and markets, and for two weeks the city carried an international glow.

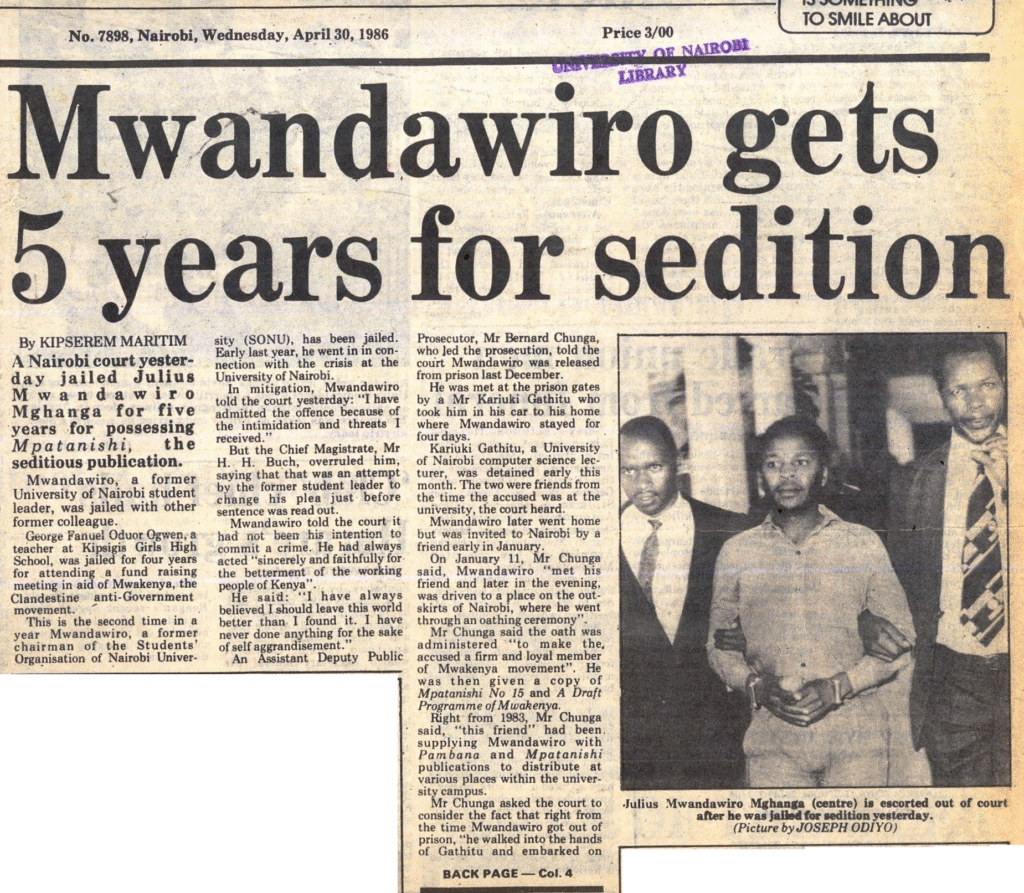

At the same time, the state was tightening its grip. The torture allegations of student leader Julius Mwandawiro made front-page news, while women activists marched for detainee rights.

The photographs reveal a split reality: global diplomacy on Harambee Avenue, political fear in the lecture halls, and a city still moving through its routines.

1986 – Crackdowns and the Nyayo Bus

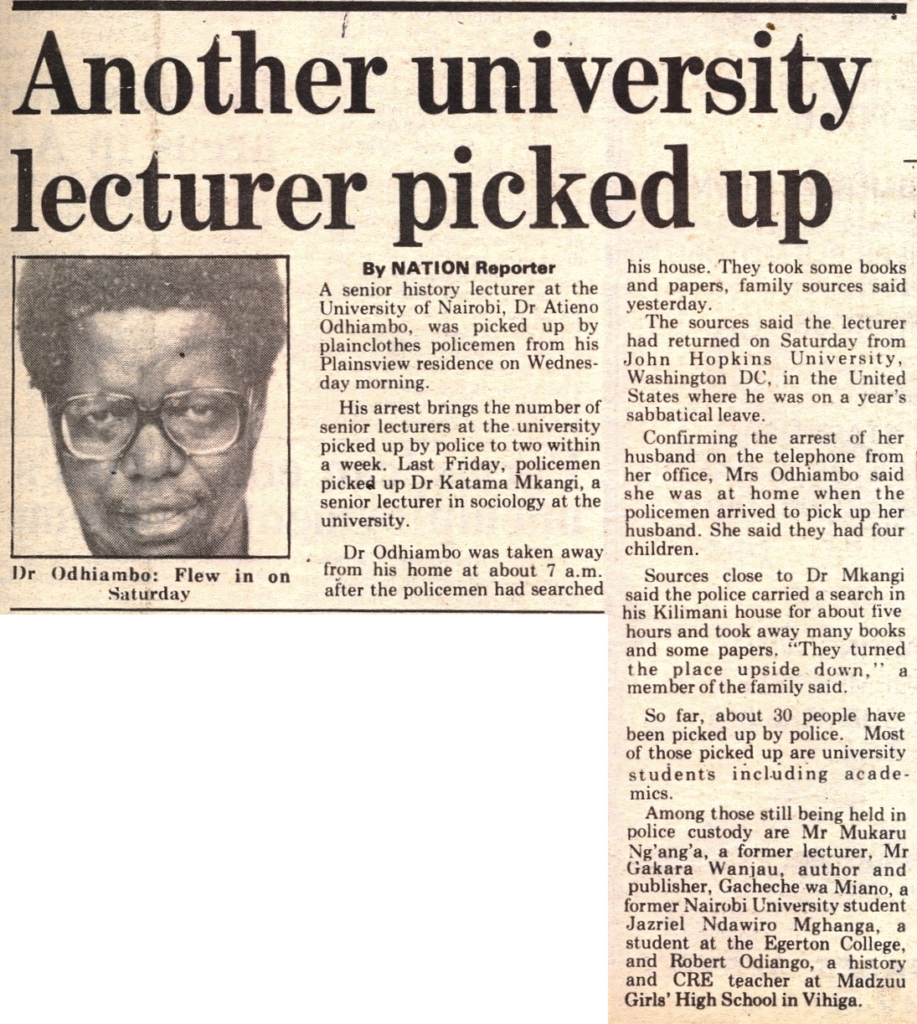

1986 saw escalated repression of intellectual life. Student leaders were jailed for sedition, lecturers detained at dawn, and universities closely monitored. Moi lectured graduates on duty and discipline as newspapers framed dissent as sabotage.

But 1986 was also a year of ambitious state projects. The launch of the Nyayo Bus Service added a distinctive new fleet to Nairobi’s roads, promising efficiency and national pride. The buses became one of the most visible symbols of the Nyayo philosophy—order, loyalty, and movement under state supervision.

Nairobi’s streets remained calm, but undercurrents of fear shaped public behaviour.

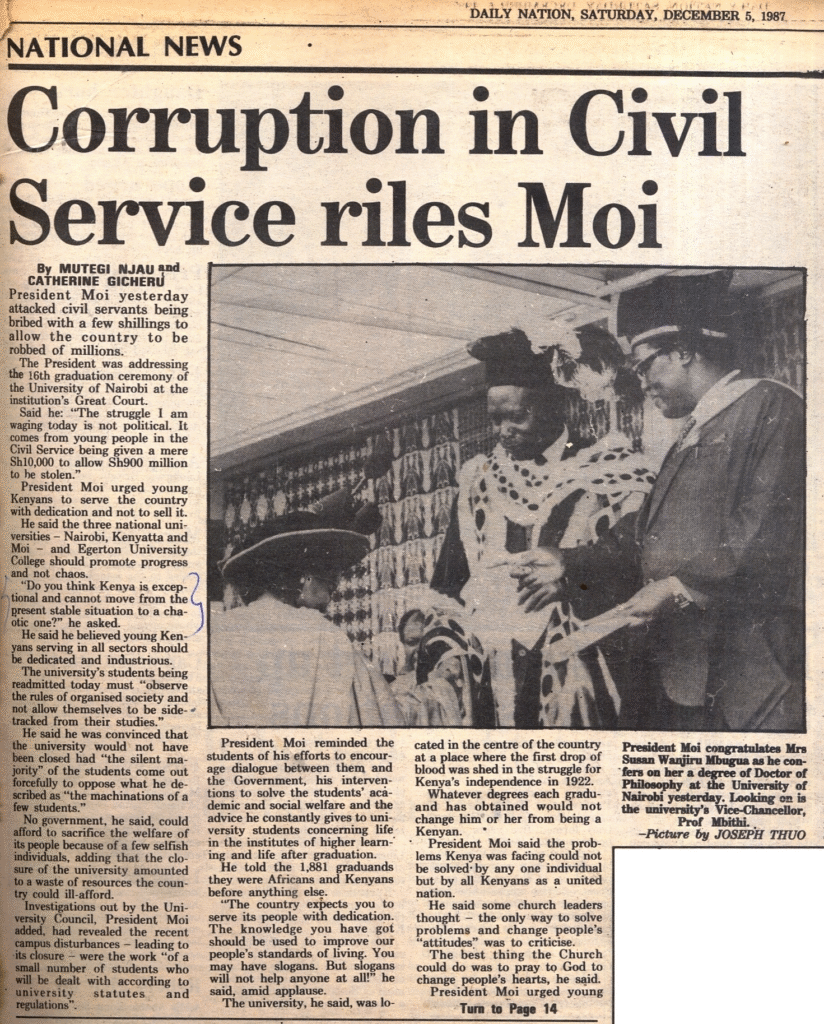

1987 – Closing Doors, Opening Games

1987 was marked by the closure of the University of Nairobi after renewed student clashes. The government’s patience with dissent had evaporated, and the city felt the pressure as campus activism was met with surveillance, arrests, and shutdowns.

Yet in the same year, Nairobi hosted the 4th All Africa Games, filling stadiums with flags, delegations, and carefully managed pageantry that projected continental leadership and national unity.

Amid this mix of tension and spectacle, one of the surviving photographs from the year captures a young Barack Obama, then in his twenties, visiting his Kenyan family. The picture, taken in Nairobi during this visit, has since become one of the most widely circulated images of his early life and adds an unexpected footnote to the city’s visual history in a politically charged year.

Street scenes from 1987 show Nairobians going about their routines while the state worked hard to maintain the optics of stability, even as political control tightened beneath the surface.

1988 – Psyops and Neglect

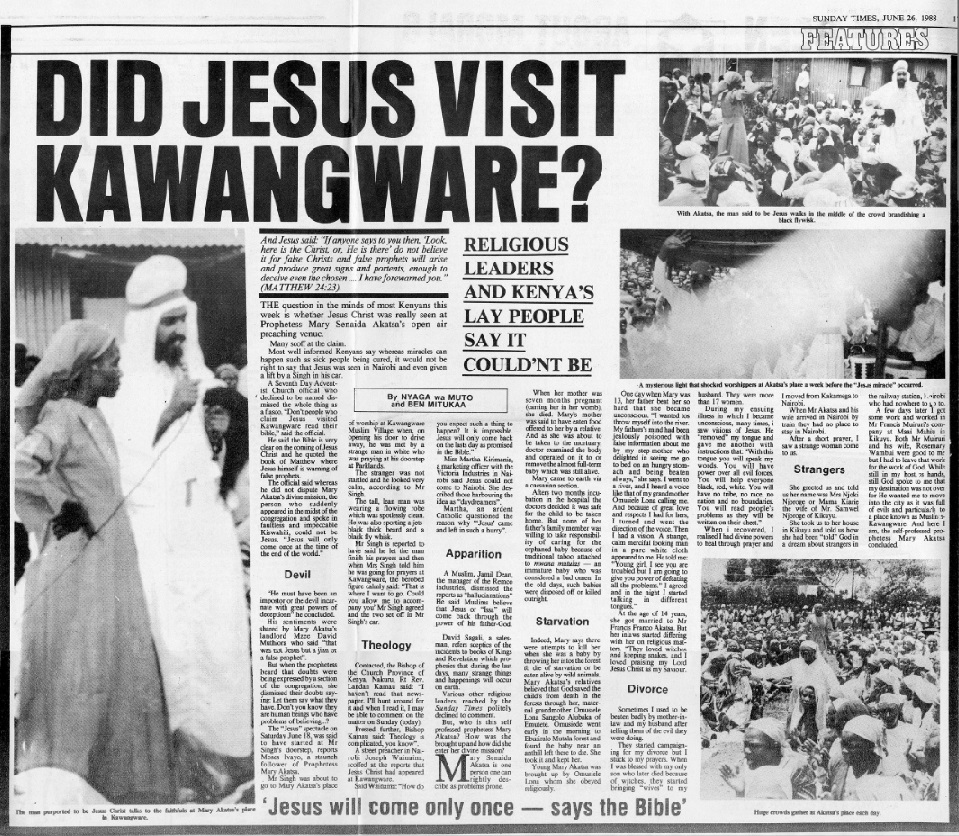

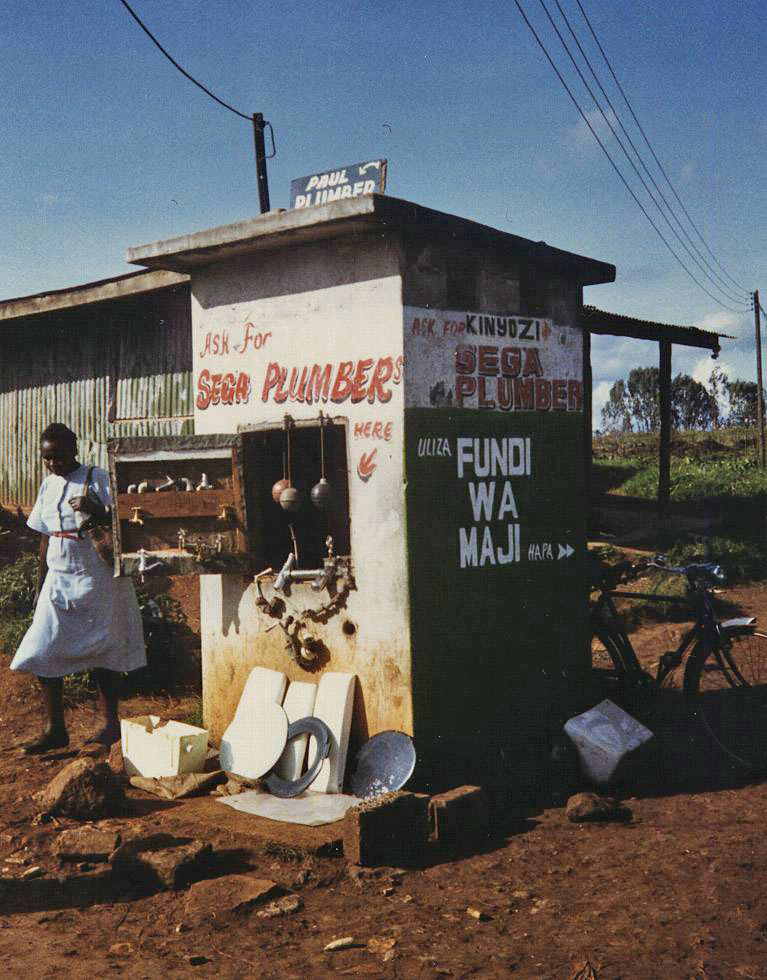

1988 is best remembered for the bizarre “Did Jesus Visit Kawangware?” saga—a psychological distraction amplified by state-friendly media while ignoring the stubborn realities of slum life.

As newspapers debated theology and miracles, Kibera and Kawangware moved on with little government attention. Small fundi kiosks, open trenches, crowded shacks, and improvised plumbing tell the real story: self-reliant communities thriving despite complete state neglect.

It was a year where propaganda dominated headlines and survival dominated the streets.

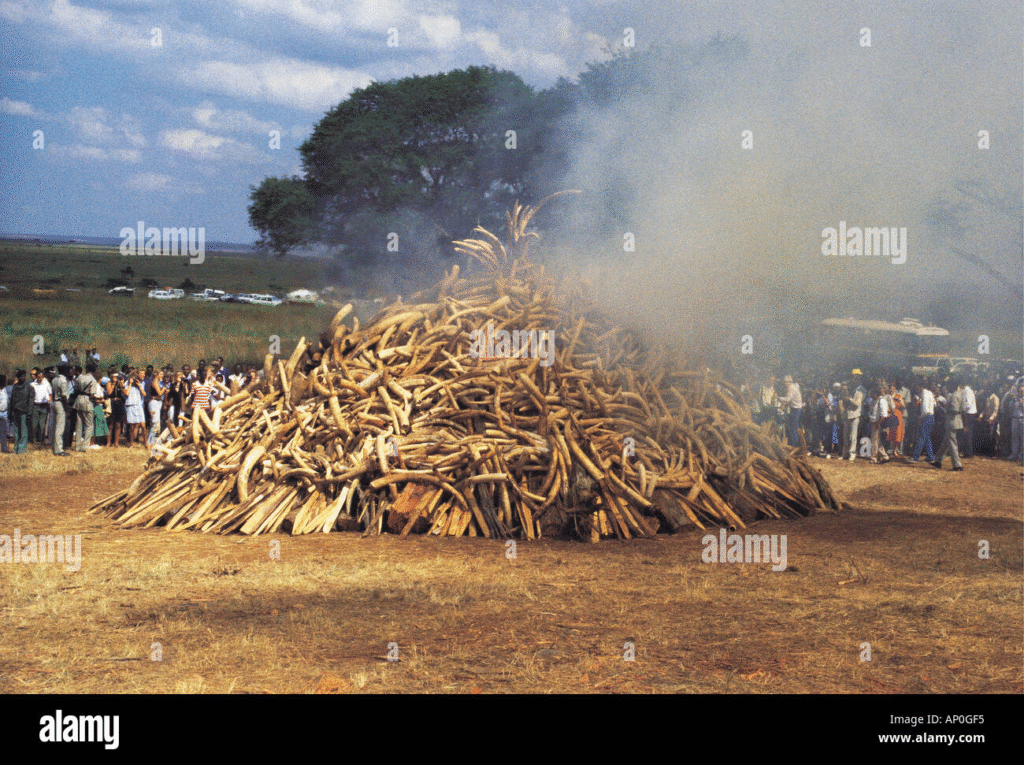

1989 – Conservation Theatre and Everyday Nairobi

1989 produced the most famous image of the Nyayo era: the ivory burn. Moi, flanked by Richard Leakey, set fire to 12 tons of tusks in a spectacle meant for global consumption.

Meanwhile, Nairobi’s day-to-day life continued unchanged. The traffic jams on Moi Avenue, matatus jostling for space, pedestrians weaving through chaos—these images remind us that beneath the conservation theatrics, Nairobians faced the same old burdens.

It was a year of two parallel stories: global applause and local fatigue.

1990 – The System Breaks Open

1990 was the year the centre finally began to crack.

Protests for political reform swept through Nairobi. Demonstrations erupted, mothers demanded the release of detainees, police ran battles in the streets, and students resisted new crackdowns.

The assassination of Dr. Robert Ouko electrified the country, and the state struggled to contain the fallout.

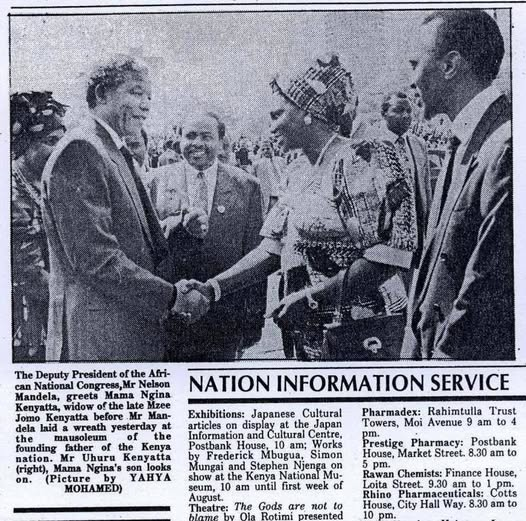

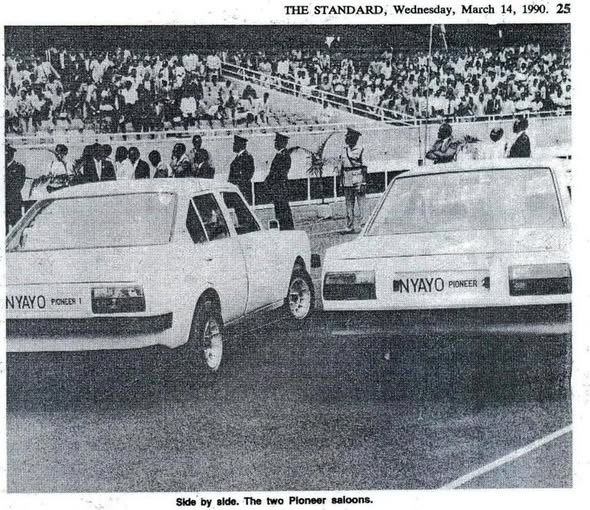

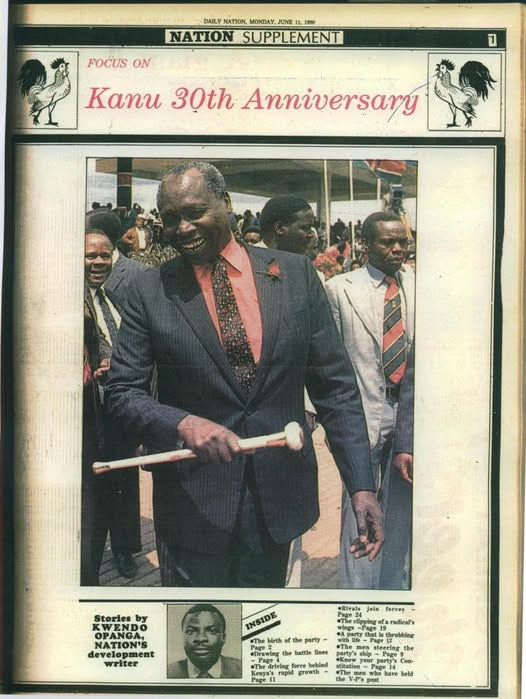

Yet the year also held moments of symbolism: Nelson Mandela’s post-prison visit, the launch of the Nyayo Pioneer car, and KANU’s 30th anniversary celebrations—rituals meant to reaffirm power even as it wobbled.

By the end of 1990, Nairobi had transformed into the frontline of Kenya’s push for multiparty democracy.

Conclusion – Twelve Years That Built and Broke a City

From 1978 to 1990, Nairobi lived through a rare blend of spectacle, fear, propaganda, and survival. The photographs trace a capital shaped by state power, student defiance, slum resilience, global visitors, and the quiet dignity of ordinary people carrying on through unpredictable seasons. These were the years that set the tone of the Nyayo state: firm, theatrical, suspicious, and endlessly demanding of its citizens.

Yet unbeknownst to almost everyone at the time, 1990 was only the half-term point, not the end of an era. Kenyans were barely halfway through a political cycle that would take another twelve years before the cogwheels of grassroots economic development could begin turning again. The city would go on to witness deeper repression, bolder resistance, and eventually, the slow reopening of political and economic space.

These photographs anchor the first movement of that long journey. They show a Nairobi that endured, adapted, and kept moving—long before change finally caught up with the country..

Recommended Next Reads

If you want to see how political power evolved in the decades before and after the Nyayo era, read:

- The Birth and Evolution of Kenya’s Multiparty Democracy – how the single-party state tightened, cracked, and finally gave way to political pluralism.

To trace the roots of the tensions that shaped 1980s Nairobi, start with:

- The Political History of Kenya’s Legislative Council, 1907–1963 – a deep dive into the colonial machinery that produced the post-independence political order.

For a wider look at Kenya’s long struggle over identity and governance, explore:

- Majimbo Dreams: Kenya’s Lost Federalism – the federal debates that haunted Kenya long before the 1980s crackdowns.

To compare another moment of national upheaval with deep urban impact, see:

- The Kisumu Massacre of 1969: Independence Betrayed – a confrontation that defined the relationship between the state and the public.

And for those who want to understand the longer arc of Kenyan political ambition and betrayal:

- Tom Mboya: The Assassinated Visionary – the story of the man whose absence shaped the Kenya that Moi inherited.