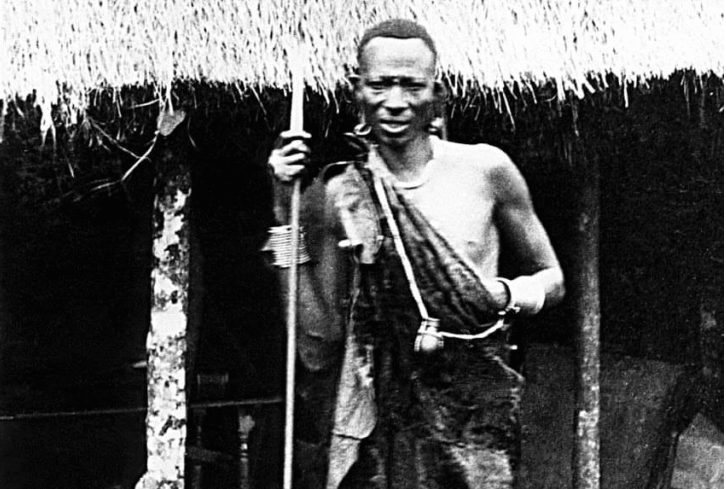

Before the name Mau Mau was ever whispered, before colonial forts rose above Kikuyu ridges, there was Waiyaki wa Hinga — chief of Southern Kiambu and one of the first Kenyans to confront empire head-on.

A Warning in the Highlands

By the late 1880s, caravans under the Imperial British East Africa Company were pushing inland, planting outposts and treaties under the guise of trade. Historian Maina wa Kĩnyattĩ records that Waiyaki recognised these moves as “the first chain links of conquest” and rallied elders from Gĩkũyũ Mbari ya Njirũ and allied lineages to resist any foreign foothold (Kĩnyattĩ, 2019).

The move mirrored early warnings sounded decades later by other local leaders who would learn that railways, maps, and forts were not symbols of progress but tools of control, as seen in The Rails That Built a Colony: East Africa’s Transport Revolution.

“To Trade, or to Steal?”

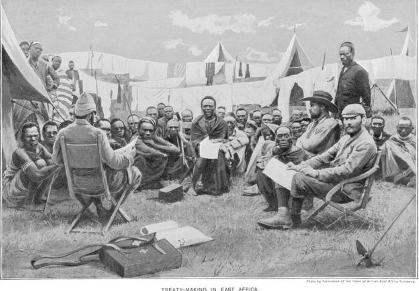

When British officer Purkiss sought an alliance in 1891, Waiyaki agreed to parley only in daylight and with his warriors present. Their exchange, preserved in Agĩkũyũ 1890–1965, turned volcanic. Asked to permit a “trading fort,” he shot back:

“Yes, to rape our women, to steal our livestock, to massacre our people — is that what you call trade? Whose country is this, yours or ours? We want you out before sunset.”

This meeting at Dagoretti marked the first coordinated armed resistance in the central highlands (Kĩnyattĩ, 2008). It shattered the illusion of Kikuyu compliance and forced the British to fortify their advance toward the Rift Valley.

Betrayal under a Flag

Peace talks followed — and treachery. Purkiss invited Waiyaki to another meeting under a white flag, only to have him seized and chained to a flagstaff before being marched to the coast. According to History of Resistance in Kenya 1884–2002, he died near Kibwezi, beaten and mutilated, his body dumped in a shallow roadside grave (Kĩnyattĩ, 2019). Oral memory insists he was buried alive for refusing to kneel.

His death foreshadowed a colonial pattern repeated in later decades — the false diplomacy, the trap disguised as negotiation — that would define the brutality exposed much later in The British Concentration Camps in Kenya.

The Siege of Dagoretti

News of his capture ignited retaliation. Gĩkũyũ fighters besieged Fort Dagoretti — a garrison built on Waiyaki’s confiscated land. Kĩnyattĩ notes that the fort’s commander admitted being “surrounded day and night by hostile Kikuyu, all of them vowing to avenge Waiyaki’s death.” The assault failed but forced the British to withdraw temporarily, marking Kenya’s first sustained military challenge to colonial intrusion.

This early defiance laid the moral groundwork for future generations who would rise under new banners — the same spirit that echoed through the forests of the Aberdares with Dedan Kimathi and the Mau Mau decades later.

Memory, Martyrdom, and the Lineage of Defiance

Scholar Charles Kebaya describes such episodes as Kenya’s “cultural archives of atrocity” — moments where violence became political memory (Kebaya et al., 2019). Waiyaki’s killing, retold in clan songs, became the archetype of that memory.

Half a century later, Dedan Kimathi would invoke Waiyaki’s name as the spark that “first lit the mountain.” In Kĩnyattĩ’s framework, Waiyaki belongs to the primary stage of Kenya’s anti-imperialist struggle (1884–1920), the foundation on which later uprisings were built.

Waiyaki’s resistance also connects to a broader arc of defiance that culminated in Kenya’s eventual sovereignty, traced in How Did Kenya Get Independence.

The Road Bears His Name

Today Waiyaki Way cuts through Nairobi — a modern highway roughly following the caravan path that once carried his chained body eastward. Every vehicle that roars over it traces the route of Kenya’s first martyr of the highlands.

His grave is unmarked, but his defiance endures. He was the first to see that “trade” meant conquest — and the first to die refusing it.

References

- Kebaya, C., Muriungi, C. K., & Makokha, J. K. S. (2019). Cultural Archives of Atrocity: Essays on the Protest Tradition in Kenyan Literature, Culture and Society. Routledge.

- Kĩnyattĩ, M. wa. (2008). Agĩkũyũ 1890–1965: Waiyaki, Kenyatta, Kĩmathi. Nairobi: Mau Mau Research Centre.

- Kĩnyattĩ, M. wa. (2019). History of Resistance in Kenya 1884–2002. Mau Mau Research Centre.