The Kamba—also known as the Akamba—are one of Kenya’s prominent Bantu peoples. With a history that stretches from ancient migrations out of the highlands near Mount Kilimanjaro to a dynamic present marked by entrepreneurship, political engagement, and vibrant cultural expression, the Kamba have long been recognized for their adaptability and resilience. This article provides a detailed, multi‑faceted account of Kamba society. Drawing on research from as early as the 1940s and incorporating more recent information, it aims to present a thorough picture of the Kamba’s origins, territorial organization, language, economic practices, social and political systems, and cultural traditions.

Table of Contents

Tribal and Sub‑Tribal Groupings

Nomenclature and Location

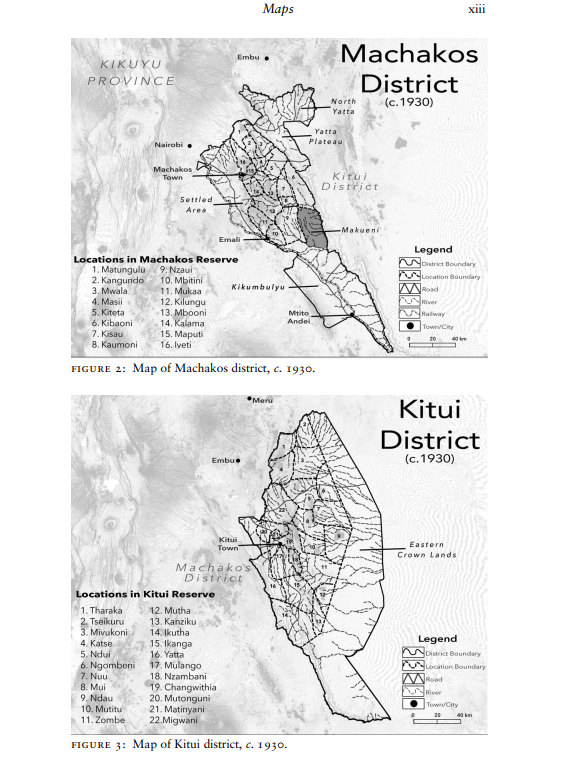

Traditionally, the Kamba (singular: Mukamba; plural: AKamba) inhabit the present‑day administrative districts of Machakos and Kitui in Kenya—a region known as Ukambani. The River Athi forms the common boundary between these districts. Within Machakos, the traditional sections are Ulu (meaning “the high country”) and Kikumbuliu (alternatively known as Kibwezi), whereas Kitui comprises the sections of Kitui and Mumoni. Although slight cultural and dialectal differences exist between these divisions, the Kamba consider themselves one people. In fact, the people of Ulu sometimes refer to those in Kitui as Adaisu or Athaisu, highlighting regional distinctions while maintaining a unified identity.

Beyond the core Ukambani region, smaller groups of Kamba have established themselves in other parts of Kenya. Communities can be found in Rabai near Mombasa, in Teita and Digo, in the area between Lake Jipe and Taveta, and even farther south in central Tanganyika. Historical evidence suggests that some of these peripheral groups migrated in search of better grazing or to escape periodic famines, while still maintaining strong trading and familial links with the parent groups. The Kamba were known by different names among their neighbors; for instance, the Masai referred to them as Lung’u, while the Swahili called them Wamanguo (derived from the word for “clothes”), meaning “the naked people.”

Neighboring Peoples and Demography

The Kamba are surrounded by a diverse mosaic of neighboring communities. To the west lie the Kikuyu, and to the northwest, the Tharaka and Mbere—peoples who share linguistic and cultural affinities with the Kamba. To the southwest, the Masai, renowned as fierce pastoralists, have historically engaged in cattle‑rustling and occasional raiding with the Kamba. In addition, groups such as the Boran, Pokomo, Boni, and Sanye (or Arangulo) reside to the northeast and east, with boundaries that, in many cases, have been fluid over time.

Demographically, the Kamba have grown considerably over the past century. According to 1948 census data, Machakos District was home to approximately 350,866 Kamba and Kitui to around 203,035. Nationwide, figures indicated about 389,777 Kamba in Machakos and 221,948 in Kitui. In addition to these strongholds, smaller communities were noted in urban and rural areas across Nairobi, Thika, Mombasa, Kwale, Kilifi, and Kajiado. More recent estimates, including those from the 2019 census, place the total Kamba population in Kenya at over 4.6 million. This expansion, combined with migration to urban centers and even diasporic communities in Uganda, Tanzania, and Paraguay, highlights the evolving yet enduring nature of Kamba identity.

Traditions of Origin and Early History

The Kamba have long maintained vibrant oral traditions regarding their origins. One prevalent narrative suggests that the Kamba were once a compact group settled in the highlands of Ulu, from where they expanded into neighboring areas. According to tradition, the Mbooni Mountains are revered as the launching point from which the Kamba migrated into Kitui and beyond. Some accounts posit that the Kamba originally came from the coastal Giriama country, while others suggest an origin near Kilimanjaro. Whatever the case, these migratory movements—dating from around 1300 AD for the initial settlement and intensifying between the 15th and 17th centuries—established the Kamba as both hunters and agriculturalists. They later acquired cattle through trade, exchanging ivory for livestock, a practice that cemented their role as intermediaries between the interior and coastal trading centers.

Colonial encounters in the late 19th century further reshaped Kamba history. The establishment of the Imperial British East Africa Company’s station at Machakos in 1892 and the subsequent setting up of administrative structures in Kitui in 1893 marked the beginning of profound change. The construction of the Kenya and Uganda Railway from 1896 onward facilitated European settlement, land tenure reforms, and an evolving market economy—changes that, over time, influenced Kamba social organization and economic practices.

Language and Communication

Kikamba and Its Dialects

The Kamba speak Kikamba—a Bantu language that is the primary medium for transmitting culture, tradition, and history. As a member of the Northern Bantu languages (Guthrie’s Zone E, group 50), Kikamba is linguistically related to Kikuyu, Embu, Meru, and Mbeere. Although the language is essentially one, distinct dialectal differences have developed between regions. For example, the dialect spoken in Machakos differs in vocabulary and construction from that of Kitui, sometimes referred to as Daisu or Thaisu. In addition, minor variations exist between the dialects of Kitui and Mumoni, and between those of Ulu and Kibwezi.

Lingua Franca and Modern Communication

Over the centuries, interactions with Arab and Swahili traders introduced Swahili as a common lingua franca in the region, facilitating trade and interethnic communication. In contemporary times, English has become increasingly prevalent, particularly in urban centers and formal educational settings. Modern media, including vernacular radio stations such as Athiani FM, Musyi FM, and television channels like Kyeni TV, broadcast in Kikamba. Online news platforms such as Mauvoo News further document and celebrate contemporary Kamba affairs, ensuring that both tradition and modernity are interwoven in daily communication.

The Physical Environment

Ecological Zones of Ukambani

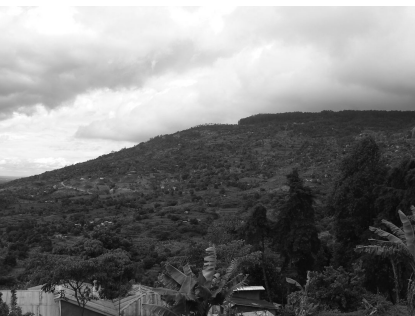

The Kamba homeland is located along the eastern slopes of the Kikuyu highlands, an area that is as ecologically diverse as it is culturally rich. Elevations gradually decrease from approximately 5,000 feet in Machakos to around 1,500 feet along the eastern boundaries, where the landscape merges with the northern parts of the Nyika desert. This varied terrain has long dictated the patterns of settlement, agriculture, and pastoralism among the Kamba.

Land Use, Water Resources, and Challenges

Much of the land in Machakos is steep and rocky, with only a fraction of the total area under cultivation. In 1932, reports indicated that of 1,400,000 acres, only about 140,000 were actively cultivated, while large portions remained fallow or were abandoned due to the tsetse fly problem. In Kikumbuliu, water is scarce, with residents relying on a few seasonal streams and the limited supplies provided by railway taps. In Kitui, settlements are primarily concentrated along the few rivers that traverse the region, with some villages located hours away from permanent water sources. These environmental challenges have necessitated a range of adaptive strategies in agriculture, such as the creation of irrigation ditches and the practice of mixed cropping.

Modern Environmental Considerations

In recent decades, the physical environment of Ukambani has continued to shape the Kamba’s way of life. Climate variability and over‑population in certain areas have led to concerns over land degradation and water scarcity. However, modern techniques—such as improved irrigation, sustainable land management practices, and government-supported development projects—are increasingly being integrated into traditional practices. These adaptations are essential for preserving the ecological balance and ensuring food security for a rapidly growing population.

Economic Activities: Past and Present

Traditional Agriculture, Livestock, and Diet

Historically, the Kamba practiced a mixed agro‑pastoral economy that remains at the heart of their identity:

Agriculture

Traditional Kamba agriculture is marked by the cultivation of a variety of staple crops. Fields are typically sited along the banks of rivers or in depressions that capture moisture, and the Kamba are adept at creating irrigation ditches to maximize water availability. The principal cereal crops include:

- Sorghum, Maize, and Millet: These grains form the dietary base and are often grown in mixed stands to optimize soil fertility and reduce the risk of complete crop failure.

- Legumes: Pigeon pea is the most popular, while other beans and peas provide essential protein.

- Root Crops: Sweet potatoes, yams, and manioc are common, serving as important sources of carbohydrates.

- Cash Crops and Fruits: In low‑lying areas, sugar‑cane is grown (sometimes in pits within valleys), and bananas are cultivated in several varieties, adding both nutritional value and commercial potential.

Livestock

The Kamba maintain substantial herds of livestock, which complement their agricultural activities. Their cattle are predominantly a short‑horned zebu type, well‑adapted to local climatic conditions. Herds are usually kept in widely dispersed kraals, a strategy that minimizes losses due to predation and theft. Seasonal cattle movements—particularly from Kitui into semi‑desert areas—have long been part of pastoral life.

Diet

The traditional Kamba diet is predominantly vegetarian. However, meat from both domestic and wild animals is also consumed, and insects such as grasshoppers provide additional protein. Dairy products, including milk and butter, play important roles; butter is used both as food and as a form of “toilet grease.” Honey is widely enjoyed, and traditional beer is brewed from sugar‑cane or honey using local fermenting agents (notably the fruit of kigelia). These dietary practices are a blend of subsistence and cultural tradition, sustained over generations.

Traditional Trade and Its Legacy

Trade has historically been of paramount importance to the Kamba. Known as expert long‑distance traders, the Kamba were instrumental in mediating commerce between the interior and the coastal regions. In the pre‑colonial era, they were involved in:

- Ivory Trade: Ivory was the main commodity, but foodstuffs, tobacco, and even slaves were also traded.

- Caravan Networks: The Kamba organized weekly caravans that traveled to the coast. They exchanged locally produced goods for beads, iron hoes, cotton cloth, red dyes, brass wires, and other manufactured items.

- Inter‑Ethnic Trade: They traded not only with coastal Arabs and Swahili but also with neighboring communities such as the Kikuyu, Maasai, and Embu.

Today, while modern commerce has evolved, the Kamba’s trading spirit remains. Many Kamba entrepreneurs are noted for their work in craft exports—especially wood carvings—as well as in other commercial activities across Kenya and internationally.

Crafts and Traditional Technologies

Kamba craftsmanship is renowned for its diversity and aesthetic quality. Traditional skills include:

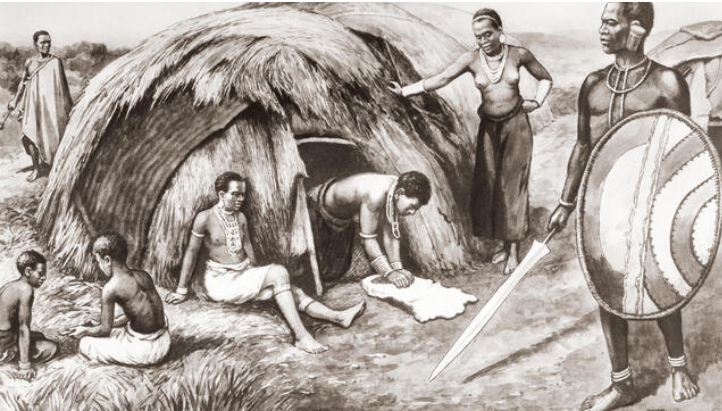

Hut‑Building

Kamba homesteads (musyi) are constructed using techniques that are both practical and symbolic. The framework is built with young trees arranged in a circle, joined at the top by cross‑wise twigs that form concentric circles. The thatched roof is supported by a strong center‑post, and the interior is divided to create a sleeping area and a central fireplace composed of three stones. Rituals mark the construction of a new hut, including the removal of iron objects and the performance of ceremonial meals and rites.

Agricultural Implements

One of the principal traditional implements is the wooden digging‑stick (mutuvu), used by women to dig or weed fields. Although these tools have largely been replaced by modern hoes and ploughs, they remain emblematic of the resourcefulness of traditional agriculture.

Branding, Wood‑Carving, and Basketry

The Kamba have a long history of working with wood and iron:

- Branding: Traditional branding irons were used to mark cattle and beehives with unique clan symbols. These irons were heated in a fire until red‑hot and then pressed onto the animal’s skin or the wooden surface.

- Wood‑Carving: Kamba artisans are celebrated for their intricate wood carvings, which adorn everything from household items to sculptures now exhibited in urban galleries.

- Basketry and Pottery: Women traditionally weave baskets from sisal or baobab bark fibers, and specialized potters craft cooking vessels from a blend of black and red clays.

Other Crafts

Additional crafts include the making of gourds and calabashes (used for storing water, milk, or beer), string and bag‑making, and even the forging of iron tools and ornaments by skilled blacksmiths. Traditional implements—such as the pestle and mortar used for pounding grains—remain a testament to the ingenuity of Kamba artisans.

Music, Dance, and Recreational Activities

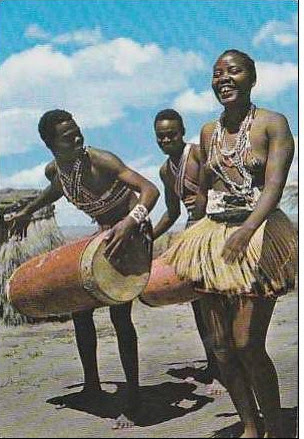

Music and dance are integral to Kamba cultural life. Traditional dances are performed on a wide variety of occasions, including:

- Ceremonial Dances: Rituals such as Kilumi—a rain‑making dance—and Ngoma are performed to invoke spiritual blessings or heal the community.

- Social and Recreational Dances: Dances like Mbalya (also known as Ngutha) provide a means for youth to entertain themselves after the day’s chores, while modern forms such as Kamandiko echo contemporary influences.

- Musical Instruments: The Kamba use a range of instruments, including drums (both single‑ and double‑membrane), musical bows, horns, trumpets, and flutes made from swamp reeds. These instruments often accompany work songs—like the famous “Ngulu Mwelela”—and ceremonial tunes that underscore the community’s vibrant spirit.

- Games and Riddles: Competitive games, riddles, and imitative play are part of everyday life, strengthening social bonds and passing cultural knowledge from one generation to the next.

Distribution of Labor

Labor in traditional Kamba society is carefully allocated along gender and age lines:

- Men’s Work: Men traditionally clear fields using iron knives, tend to livestock (which includes herding cattle and sheep), and engage in trade and hunting. They also participate in heavy craft work, such as iron‑forging and wood‑carving.

- Women’s Work: Women are principally responsible for tending household gardens, processing food, making pottery, and weaving baskets. They also care for young children and perform milking duties.

- Extended Family and Community: The extended family (muvia) and larger groupings such as the utui and kivalo ensure that labor is shared, with older members (including grandparents) assisting with tasks such as rope‑making, leather tanning, and other less strenuous activities.

Social Organization and Political Systems

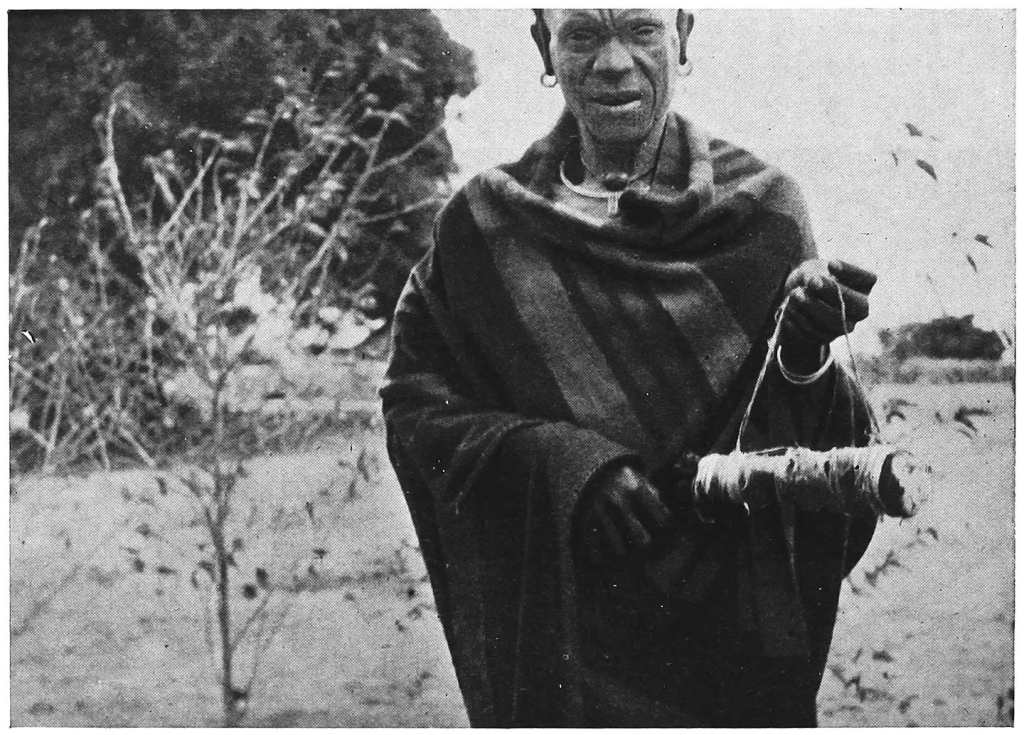

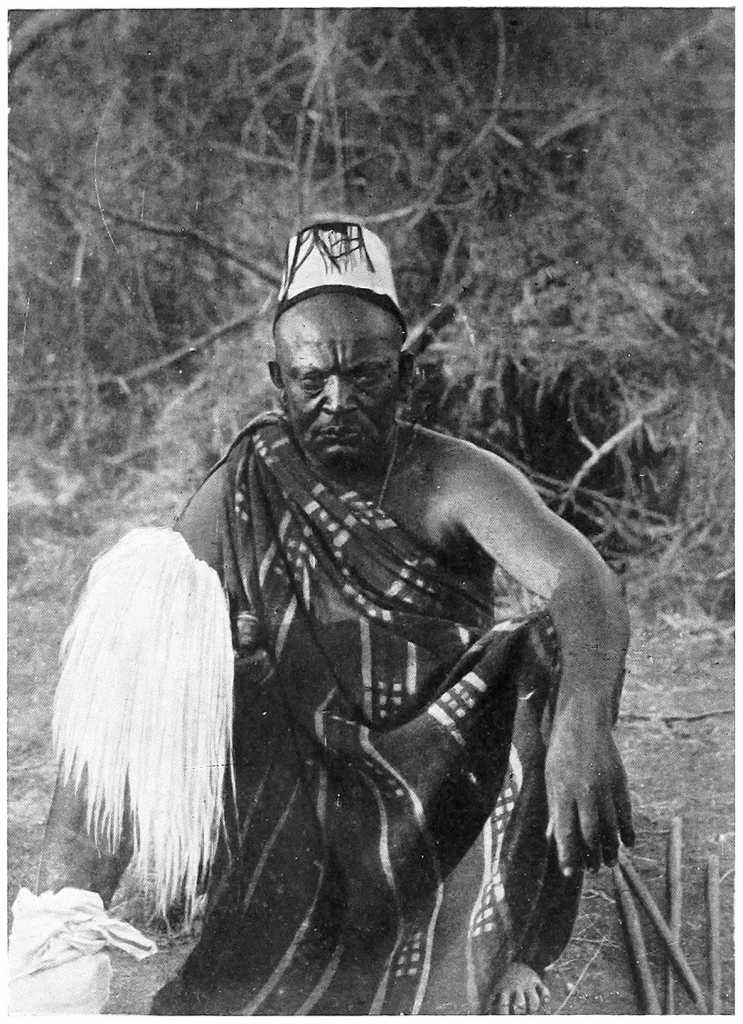

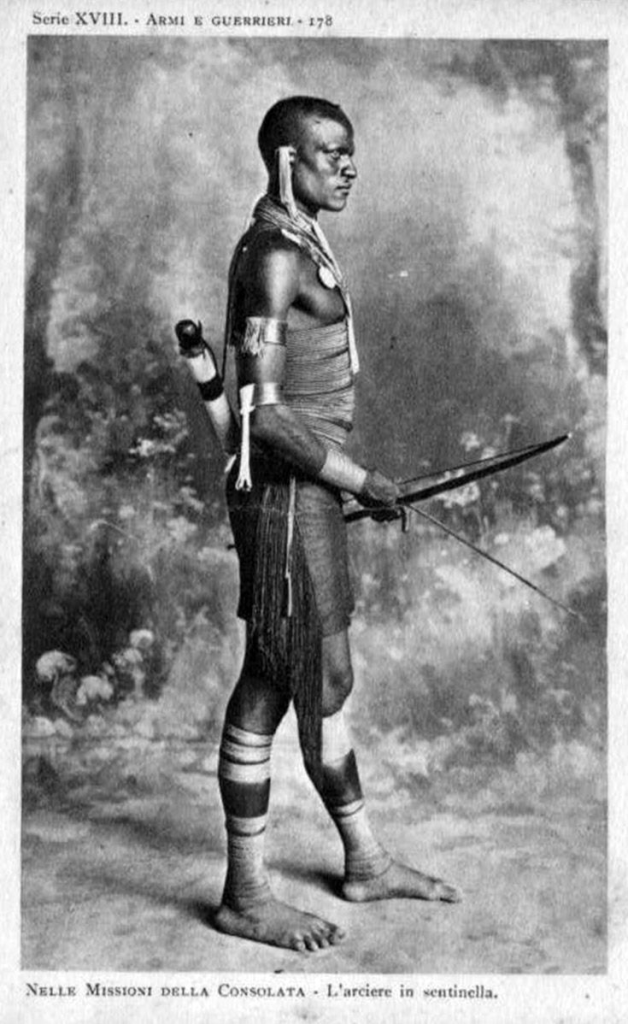

A KAMBA CHIEF.

Kinship, Clan, and Fictional Kinship

The Kamba social structure is fundamentally kinship‑based. At its core, the family is organized into the musyi—a homestead that is home to a joint or extended family (muvia). Kinship terms, which sometimes vary between regions (Ulu versus Kitui), govern everyday interactions. In addition to biological relationships, the Kamba also practice “fictional kinship,” wherein sworn brotherhoods—sealed by rituals such as sharing a drop of blood—create bonds equivalent to siblinghood. These relationships ensure mutual assistance, protection when traveling, and strict prohibitions on intermarriage among sworn brothers and their descendants.

The Clan System

The Kamba are divided into approximately 25 patrilineal, totemic clans. Each clan is generally named after a founding ancestor or a notable characteristic, and inter‑clan relations are maintained by regular visits and shared rituals. Clan members observe totemic prohibitions—for instance, members of a clan will neither kill nor eat their totem animal (often a lion, hyena, or other animal), as it is seen as a sacred symbol of their identity. Totemic observances help preserve clan solidarity, though modern influences have led to a decline in some traditional practices.

Territorial Organization: From Musyi to Nthi

Kamba territory is organized on multiple levels:

- Musyi and Thome: The smallest unit is the musyi (homestead), protected by a stockade and occupied by the extended family. Outside the musyi lies the thome—a shaded open space where men convene to discuss community matters and resolve disputes.

- Utui (Motui) and Kivalo (Ivalo): Several musyi combine to form an utui, a territorial unit that possesses its own institutions, such as a men’s club (kisuka), recreation ground (kituto), elders’ council (nzama), and a place of worship (kitunyeo kya ng’ondu). Neighboring utui may share these institutions, while a larger grouping called kivalo brings together several joint families. The kivalo serves not only as a basis for inter‑marriage and social cohesion but historically also functioned as a military unit during times of war.

- Nthi (“Country”): The widest territorial unit is known simply as nthi. Although it may have a specific name, an nthi does not possess its own distinct social institutions apart from those established by later colonial administration.

Age‑Grade System

The Kamba institutionalize an age‑grade system that is central to social organization and political responsibility:

- Youth: A male child begins as a kaana (encompassing both the unweaned and early weaned child) and then becomes a kavisi (a weaned child capable of walking). As he grows, he enters the stage of kamwana (a circumcised boy who is old enough to dance but has not yet reached puberty).

- Warrior and Mature Phases: Upon reaching puberty, he is initiated into the rank of mwanake (warrior). While a mwanake may marry and have children, he is traditionally forbidden from drinking beer until he transitions into the next stage, becoming nthele—a married man with children who no longer dances. This transition involves the payment of a ceremonial fee (typically in goats) to signal his promotion.

- Elderly Grades: Later in life, men join the elders’ grades. The lower elder grades (atumia ma kisuka) are responsible for community discussions and ritual duties, including the disposal of corpses and the supervision of communal rituals. Higher grades, forming the nzama (administrative council) and eventually the nzili (inner council), carry out advanced ritual and judicial functions. Membership in these councils is determined by age, lineage, and the payment of fees; in some cases, younger men may be forced to retire from the highest grade if a new heir is ready to take their place.

Legal Procedure and Local Governance

Local governance among the Kamba is administered according to customary law:

- Homestead Authority: The head of each musyi exercises considerable power over the family, managing daily affairs and adjudicating disputes. The musyi also functions as the unit for land tenure, with collective responsibility for seeking compensation (or blood‑money) in cases of injury or homicide.

- Elders’ Council: At the level of the utui, the elders (nzama) serve as arbitrators and judges. They resolve private delicts (offences between individuals) through compensation rather than punishment. In cases of serious or public offences, a judicial process known as king’oli may be invoked, similar in nature to systems in neighboring communities.

- Oaths and Ordeals: To settle disputes or confirm truth, the Kamba use oaths (such as the kithitu) and ordeals—ritual tests involving, for example, the licking of a heated knife. These practices, imbued with the threat of supernatural retribution, ensure that disputes are resolved with community sanction and that offenders face both material and metaphysical consequences.

- Land Tenure and Inheritance: Land is held communally by the extended family (muvia) and is used both for cultivation (ng’undu) and grazing. Inheritance is based on a matri‑segmented system: land passes primarily to a wife’s children, with specific rules governing the sale, transfer, or mortgaging of land rights. Such arrangements ensure that property remains within the joint family and that traditional usage rights are preserved.

Main Cultural Features

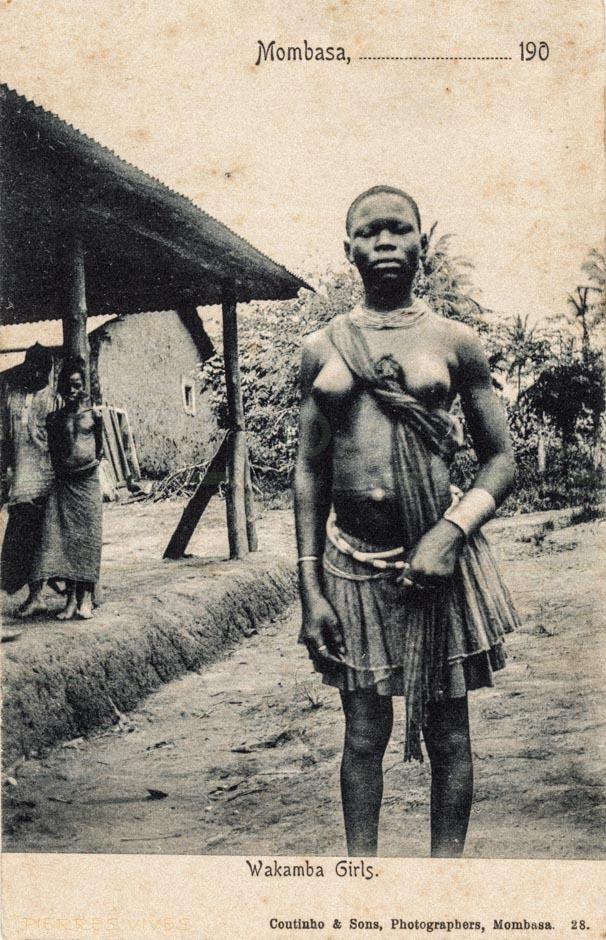

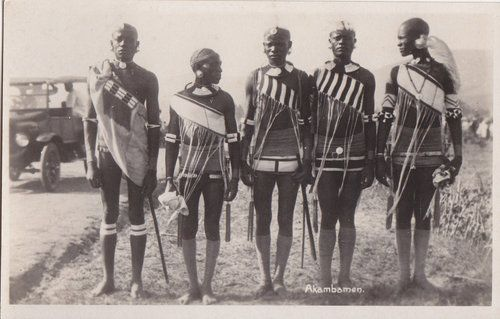

Dress and Ornamentation

Traditional Kamba dress was characterized by simplicity and function:

- Men’s Dress: Traditionally, Kamba men often went without clothing or wore only minimal coverings. Over time, especially with the arrival of cloth from the coast, men adopted garments in white or blue, typically treated with fat and ochre. In earlier times, leather kilts made from animal skins or tree bark were common.

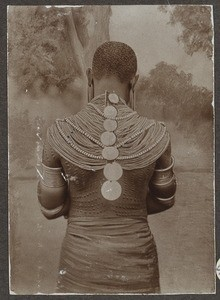

- Women’s Dress: Married Kamba women traditionally wore calf‑ or goat‑skin attires rubbed with ochre. Girls initially wore rectangular loin‑cloths with leather‑strapped aprons. Today, European‑style clothing is widespread, yet traditional ornaments—such as beaded necklaces, bracelets, and rings—remain integral. These ornaments vary with age and social status and are often made from locally available materials like copper, brass, and beads.

- Costumery and Adornments: Both men and women embellish their bodies with beads, necklaces, and rings. Traditional hairstyles, the use of ochre for body decoration, and practices such as tattooing and teeth‑chipping (to create pointed incisors) have long been part of Kamba aesthetics.

Life Cycle Rituals

Kamba life is punctuated by elaborate rituals that mark major transitions:

- Birth: When a child is born, several rituals ensure that the newborn is accepted as a human being. For example, before birth, all iron objects are removed from the homestead. After the birth, a ceremony is held in which the father fetches sugar‑cane, and on the fourth day, the child receives an iron necklace. A child is not fully integrated into the community until these rites have been completed.

- Initiation: Both boys and girls undergo circumcision rituals known as nzaiko. The first, nzaiko nini, is performed when children are as young as four or five years old. The more significant nzaiko nene occurs at puberty and is accompanied by a period of seclusion, communal instruction, ritual dances, and tests of courage. Boys learn skills such as herding and hunting, while girls are taught domestic responsibilities and how to raise a family. A third, more secretive initiation rite—the circumcision of men (nzaiko ya aume or mbavani)—occurs less frequently and is shrouded in secrecy.

- Marriage: Kamba marriages are traditionally arranged. A suitor initiates the process by sending gifts such as three goats to the prospective bride’s father. Bridewealth (theo or ngasia) is negotiated based on the suitor’s economic standing, traditionally involving a combination of livestock and, later, cash or other modern substitutes. After the bridewealth is paid, a ceremonial “abduction” takes place, and the bride is brought to her husband’s home.

- Death and Burial: Funeral rites among the Kamba vary by region. In some areas, only elders and first wives are interred while other bodies are left in the bush. In more densely populated areas, every death is marked by burial in a round, shallow grave, with specific orientations for men (facing east) and women (facing west). Mourning practices are highly ritualized, with prescribed periods of abstinence and purification to protect the community from the ancestral curse.

Religious Beliefs and Ritual Practices

Religion in Kamba society is a blend of monotheism and ancestral veneration:

- Supreme Deity: The Kamba believe in a single, transcendental God known as Ngai or Mulungu (also called Asa or Ngai Mumbi). This deity is invisible, omnipotent, and resides in the sky, yet is considered distant from daily human affairs.

- Ancestor Spirits: The spirits of the dead, known as aimu or maimu, play a central role as intermediaries between the living and Ngai. These ancestor spirits are believed to dwell in natural settings—often fig‑trees or prominent rocks—and are appeased with regular offerings and sacrifices.

- Shrines and Sacrifices: The Kamba construct sacred groves known as ithembo, where communal sacrifices (often of goats or other animals) are offered to invoke rain, ensure fertility, or restore harmony after misfortune. The rituals performed at these shrines are administered by elder specialists and often involve purification rites using natural elements, such as parts of specific plants or animal products.

- Magic, Sorcery, and Spirit Possession: Traditional healers (mundu mue) and sorcerers (mundu mwoi) wield considerable influence. They employ divination techniques—using calabashes, drumming bows, and the interpretation of dreams—to diagnose illnesses and predict future events. Spirit possession, particularly during dances, is regarded as a means for the ancestors to communicate, with exorcisms typically performed through ritual dance movements. Although these practices have diminished in frequency since the advent of modern medicine and religion, they remain an important part of the cultural landscape.

Music, Dance, and Celebratory Practices

Music and dance are vital expressions of Kamba culture, both as vehicles for ritual communication and as modes of entertainment:

- Traditional Music and Instruments: The Kamba use a variety of instruments, including drums (of single and double membranes), musical bows with calabash resonators, horns, trumpets, flutes (often made from swamp reeds), rattles, and bells. These instruments provide the rhythmic backbone for work songs and ceremonial performances.

- Dances: Traditional dances—such as Kilumi, a rain‑making and healing dance, and Ngoma, performed during religious ceremonies—display the Kamba’s athleticism and creativity. Dances are performed by all age groups, and many are accompanied by songs that satirize social vices or celebrate communal achievements.

- Modern Recreational Activities: Contemporary Kamba music, dance, and art have evolved yet continue to draw on traditional themes. Popular musicians such as Ken Wamaria and other noted artists, as well as vernacular media (radio stations like Athiani FM, Mang’elete FM, and Syokimau FM, along with Kyeni TV), help keep the Kamba cultural heritage alive in a modern context.

The Kamba Family and Social Structure

At the heart of Kamba society is the family:

- Musyi (Homestead): The homestead is the fundamental unit of social organization. It is typically occupied by an extended family (muvia), which may span three or four generations. The musyi is not only a residential unit but also the center of land tenure and local justice.

- Gender Roles and Labor: Traditionally, men head the musyi and are responsible for tasks such as trading, herding, and heavy craft work, while women manage the household, tend to small gardens, process food, and engage in basket‑weaving and pottery. Children are raised within this extended family structure, with aunts and uncles playing significant roles in their upbringing.

- Naming Traditions: Naming is a sacred and systematic process among the Kamba. The first four children are usually named after the grandparents on both sides, while later children may receive names reflective of circumstances of birth (e.g., “Kiloko” for a child born in the morning) or qualities that the parents hope the child will embody (such as “Mutongoi” for a future leader).

Political Organization and Legal System

The Kamba traditionally governed themselves through decentralized systems that emphasized collective decision‑making:

- Local Governance: The basic political unit is the musyi, with authority vested in the family head. The communal outdoor space (thome) in front of the musyi serves as a forum for discussion, dispute resolution, and communal decision‑making.

- Utui and Kivalo: Several musyi form an utui, a village‑like unit with its own elders’ council (nzama), war leaders (athiani), and sacred spaces for worship (kitunyeo). Several utui can further unite to form a kivalo, a larger grouping that facilitates inter‑marriage, trade, and collective defense.

- Elders’ Councils and Age‑Grades: Elders, drawn from a formalized age‑grade system, play the role of judges and administrators. They settle disputes through compensation rather than punishment and use rituals, such as the oath‑taking kithitu, to enforce community norms. Traditional legal procedures include ordeals (e.g., licking a heated knife) and the administration of blood‑money, which serves as the primary sanction in cases of homicide or serious assault.

- Land Tenure and Inheritance: Land is held communally within the extended family. Inheritance is traditionally matri‑segmented—land and other assets pass from a husband to his wives and their children. Rules governing land sales, mortgages, and transfers ensure that property remains within the family and that customary boundaries are maintained.

Cultural Transformation and Modern Developments

The Impact of Colonialism and Independence

The colonial era brought profound changes to Kamba society. The establishment of European administration, the construction of the Kenya and Uganda Railway, and the influx of foreign settlers disrupted traditional land tenure, trade, and social organization. Despite these disruptions, the Kamba adapted by integrating aspects of modern governance and commerce while retaining their cultural heritage. During the struggle for independence, many Kamba—such as the celebrated leaders Paul Ngei, JD Kali, and others—played pivotal roles in the anti‑colonial movement. Their contributions, combined with the resilience of traditional practices, laid the foundation for a renewed Kamba identity in post‑colonial Kenya.

Contemporary Economic and Social Life

Today, the Kamba remain an integral part of Kenya’s socio‑economic fabric. While many still engage in agriculture, pastoralism, and traditional crafts, a growing number have entered modern professions. Kamba entrepreneurs, professionals, academics, and artists have made significant contributions to Kenya’s national development. Urbanization has also led to a re‑evaluation of traditional practices as the Kamba balance cultural heritage with modern lifestyles.

Modern media has played a significant role in the resurgence and preservation of Kamba culture. Vernacular radio stations, such as Athiani FM, County FM, Mang’elete FM, Mbaitu FM, Musyi FM, and Syokimau FM, broadcast in Kikamba, while television channels like Kyeni TV provide local programming. Online platforms like Mauvoo News also ensure that current events and cultural narratives continue to be disseminated widely.

Celebrating Kamba Heritage Today

The Kamba are celebrated for their remarkable artistic talents—especially in wood‑carving, basketry, and pottery. Traditional crafts are not only sold locally but also exported to international markets, reflecting a successful fusion of ancient practices with modern entrepreneurial spirit. Festivals, traditional dances (such as Kilumi and Ngoma), and public ceremonies continue to mark significant cultural events. For example, the annual celebrations that commemorate the prophetic legacy of figures like Syokimau underscore the enduring significance of traditional spirituality.

Notable modern figures from the Kamba community have achieved prominence in various fields. Politicians such as Charity Ngilu, cultural icons like the acclaimed musician Ken Wamaria, and numerous academics and business leaders have contributed to the vibrant tapestry of contemporary Kamba life. In sports, figures such as marathoner Patrick Makau Musyoki have brought international acclaim, while in the arts, individuals like fashion designer Alex Mativo exemplify the creative flair that has long been a hallmark of the Kamba.

Challenges and the Way Forward

Despite the vibrancy of modern Kamba culture, challenges remain. Issues such as land degradation, water scarcity, and the pressures of urbanization continue to affect communities in Ukambani. Nevertheless, a renewed emphasis on sustainable practices—integrating traditional knowledge with modern technology—offers hope for addressing these challenges. Cultural revival projects, supported by government and non‑governmental organizations, aim to preserve traditional language, crafts, and rituals, ensuring that future generations of Kamba can continue to draw on their rich heritage.

Furthermore, efforts to document and celebrate Kamba history through museums, academic research, and media outreach are contributing to a broader understanding of their contributions to Kenyan society. The National Museums of Kenya, for instance, showcase Kamba cultural artifacts—from intricately carved wooden sculptures to traditional musical instruments—allowing both locals and visitors to appreciate the depth and diversity of Kamba heritage.

Conclusion

The history of the Kamba people is a story of resilience, adaptation, and vibrant cultural continuity. From ancient migrations and the development of intricate kinship and clan systems to their roles as traders, artisans, and freedom fighters during the colonial period, the Kamba have forged a unique identity that is as dynamic as it is enduring. Traditional practices—whether in agriculture, trade, or ritual—continue to shape everyday life even as the community adapts to the challenges of modernity.

Today, the Kamba are not only custodians of a rich cultural heritage but also active participants in Kenya’s modern economy and political life. Their traditional values, blended with contemporary achievements, ensure that the legacy of the Kamba remains a vital and inspiring part of Kenya’s national identity. As communities work to preserve the language, crafts, and rituals of their ancestors while embracing new opportunities, the story of the Kamba serves as a powerful reminder of the enduring strength of cultural heritage in a rapidly changing world.

By understanding the complex tapestry of Kamba history—from the organization of their musyi and thome to the rich symbolism of their initiation rituals and religious practices—we gain insight into a society that has continuously reinvented itself. Whether through the echo of ancient songs, the skilled artistry of wood‑carvers, or the dynamic pulse of modern media, the Kamba continue to thrive, demonstrating that even in the face of modern challenges, the bonds of tradition and community remain unbreakable.

In celebrating the Kamba, we not only honor a people with a storied past but also recognize their ongoing contributions to the cultural, economic, and political life of Kenya and beyond. As new generations embrace both modernity and tradition, the Kamba stand as a testament to the power of resilience, innovation, and the enduring human spirit.

References

The sources for this article include a blend of mid‑20th‑century research and contemporary publications. Key references include:

- Lindblom, 1920; Hobley, 1910, 1911, 1922; Dundas, 1913, 1915, 1921; Lambert, 1947; Penwill, 1950; Larby, 1944; Kenya Land Commission Evidence, 1932; and various modern census data and academic studies, such as those published by the Kenya National Bureau of Statistics (2019) and articles on the Joshua Project and Machakos.org.

- Additional information on contemporary Kamba culture and achievements is drawn from recent news articles, academic dissertations, and ethnographic studies available on platforms such as Mauvoo News, Ethnologue, and the National Museums of Kenya.

Where’s the place of the Angulya People in your story?

You justy brought it to my attention and i find it very interesting but it appears there are not many studies present on this part of kamba history. I have began research and am hoping i can come up with something worth including here i am also open to you suggestions on where best to find info