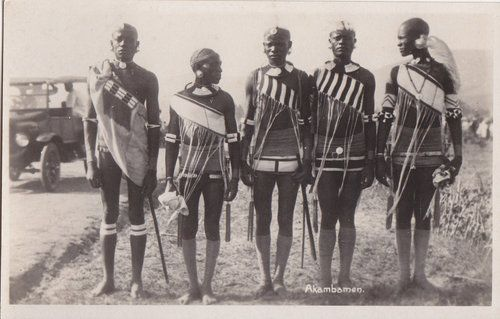

The Kamba, or Akamba, are one of Kenya’s largest Bantu-speaking communities, traditionally inhabiting the semi-arid plateau region of Ukambani in south-eastern Kenya. This homeland today covers Machakos, Kitui, and Makueni counties, though significant Kamba populations have migrated to Nairobi, Mombasa, and overseas. Over centuries, the Kamba earned a reputation as long-distance traders, skilled craftsmen, and adaptable farmers, navigating an environment where rainfall is unpredictable and survival often depended on mobility, resource-sharing, and social cohesion (Lambert, 1956).

Central to Kamba identity is the clan system (mbai in singular, mikai in plural), which forms the backbone of their social organization. More than a genealogical marker, the clan historically determined a person’s rights and duties within the community: it regulated marriage alliances, governed inheritance of land, assigned ritual responsibilities, and provided a network of mutual aid in times of famine, conflict, or migration (Middleton & Kershaw, 1965). For much of Kamba history, to know one’s clan was to know one’s place in the moral and political landscape of Ukambani.

The endurance of this system, even through the upheavals of colonialism, Christianity, and urbanization, underscores its deep-rooted significance. Understanding the Kamba clan structure is therefore not simply an exercise in ethnography—it is a window into how the Akamba have maintained a coherent cultural identity while adapting to the changing demands of history (Ndeti, 1972).

Structure of the Kamba Clan System

The Kamba clan system is fundamentally patrilineal and exogamous, meaning clan membership is inherited through the male line, and individuals are prohibited from marrying within their own clan (Lambert, 1956). The term for a clan in Kamba is mbai (plural mikai), and each clan is believed to trace its descent from a single male ancestor, whether mythical or historical (Middleton & Kershaw, 1965). This ancestral connection is reinforced through oral traditions, which recount the origins, migrations, and notable achievements of the founding lineage.

Within each clan, there are localized sub-lineages that occupy specific territories. These smaller units, sometimes referred to as mbai sya ithembo (lineages of the shrine), serve as the primary custodians of clan land and are responsible for organizing communal rituals, settling disputes, and managing shared resources (Ndeti, 1972). This territorial organization meant that while all members of a clan recognized each other as kin, social and political obligations were strongest within the local lineage.

Geographical variation is evident in the distribution of clans across Ukambani. Some clans, such as the Aombe and Amutei, are more prominent in Machakos, while Amwilu and Amuthiani have a stronger presence in Kitui. This uneven distribution is a product of historical migration patterns, intermarriage, and the ecological adaptations of different regions (Lambert, 1956).

Many clans also maintain totemic symbols—usually animals or natural elements—linked to their origin myths. These totems often function as emblems of identity and are sometimes associated with taboos. For example, a clan whose totem is a particular animal might prohibit its killing or consumption, believing such an act could invite misfortune. The totem thus reinforces the clan’s distinctiveness within the broader Kamba community while fostering a sense of continuity with ancestral traditions (Middleton & Kershaw, 1965).

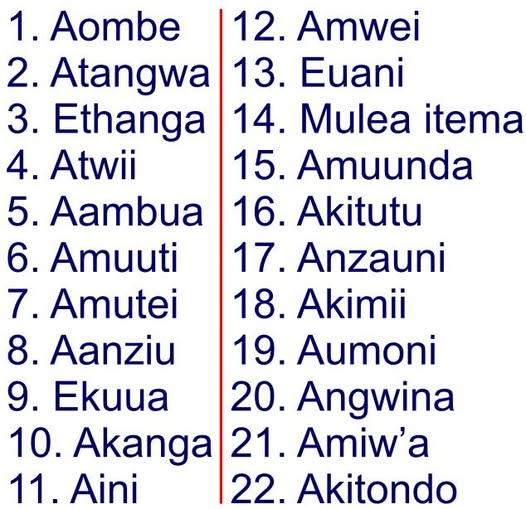

List of Major Clans

Ethnographic studies by Lambert (1956), Middleton and Kershaw (1965), Ndeti (1972), and Muthiani (1973) record numerous Kamba clans, each with its own oral history, regional concentration, and, in some cases, totemic association. While spelling variations occur between Machakos, Kitui, and Makueni dialects, the following list represents the major clans consistently identified across sources:

- Amutei – Often cited as one of the oldest clans in Machakos. Oral traditions link them to early settlement patterns in the Iveti Hills, with some narratives suggesting migration from the north before consolidating in Ukambani.

- Amuteva / Amuteve – Regarded in oral accounts as a branch of the Amutei, they are prominent in Kitui and are sometimes associated with blacksmithing traditions.

- Amwilu – Traditions connect this clan to migration from the Taita Hills region, with settlement in the eastern parts of Kitui County. Known for their trade and craft skills.

- Amutea – Found in several districts but with higher concentrations in central Ukambani. Historical accounts note their participation in long-distance trade.

- Amuvia – Concentrated in Makueni and parts of Kitui. Oral tradition emphasizes their agricultural expertise, especially in millet cultivation.

- Aombe – Strong in Machakos and associated with caravan trading routes of the nineteenth century, particularly to the coast.

- Atwii / Atui – Known in Kitui and eastern Ukambani. Oral histories depict them as among the later arrivals, integrating through intermarriage and alliance.

- Ambua – Common in Makueni. Some oral traditions associate them with distinct initiation customs and rainmaking rituals.

- Akitutu – Smaller in number and scattered across various regions. Oral accounts highlight their skilled woodcarving.

- Amuthiani – Concentrated in Kitui and eastern Makueni. Oral tradition ties them to the craft of woodcarving and spiritual mediation.

- Aombo – Sometimes considered a sub-branch of the Aombe, with strong presence in Machakos.

The persistence of these clan names across generations reflects the stability of Kamba kinship structures, even as migration and intermarriage have diversified their geographical distribution (Lambert, 1956; Middleton & Kershaw, 1965; Ndeti, 1972; Muthiani, 1973).

Social Functions of Clans

The Kamba clan system historically served as the foundation for regulating social relationships, resource use, and political authority. Its functions extended beyond kinship into every sphere of community life.

Marriage Rules and Prohibitions

Clans are strictly exogamous, meaning marriage within one’s own clan is prohibited. Such unions were traditionally considered incestuous and carried both social stigma and spiritual danger (Lambert, 1956). To avoid this, marriage negotiations required careful identification of a prospective spouse’s clan ancestry. Exogamy not only prevented inbreeding but also encouraged alliances between different clans, creating broad networks of mutual obligation (Middleton & Kershaw, 1965).

Land Ownership and Inheritance

Clan membership determined an individual’s rights to cultivate and inherit land. Land was held collectively by the lineage, with elders serving as custodians and arbiters in disputes (Lambert, 1956). Access to land was thus both a birthright and a communal trust, and transfers outside the clan were traditionally discouraged to preserve ancestral holdings (Ndeti, 1972).

Ceremonial Duties and Ritual Roles

Certain clans historically specialized in ritual functions. For example, some provided rainmakers, while others oversaw initiation ceremonies or acted as custodians of sacred sites (ithyululu) (Ndeti, 1972). Ritual responsibilities reinforced the clan’s spiritual authority and interdependence within the wider Kamba society.

Alliances and Mutual Aid

Intermarriage between clans created bonds of reciprocity. In times of famine, warfare, or migration, these ties were activated to ensure the sharing of resources, protection, and support. Clan solidarity was a critical survival mechanism in Ukambani’s semi-arid environment (Muthiani, 1973).

In this way, the clan system operated as both a social safety net and a governance structure, integrating economic, legal, and religious life into a unified kinship framework.

Changes Over Time

The Kamba clan system has endured for centuries, but its form and influence have been reshaped by historical forces such as colonial governance, Christian mission activity, and patterns of migration and urbanization.

Impact of Colonial Administration

British colonial rule altered the clan’s traditional authority, particularly in matters of land and governance. The introduction of individual land registration under ordinances such as the Native Lands Trust Ordinance eroded the lineage-based control of territory (Lambert, 1956). Colonial officials also utilized clan structures for administrative convenience, particularly in recruiting carriers and soldiers during World War I and World War II, which both reinforced and transformed clan-based obligations (Middleton & Kershaw, 1965).

Influence of Christianity

The arrival of Christian missionaries in the early 20th century disrupted certain ritual functions of clans, especially initiation ceremonies and rainmaking practices. Mission schools discouraged clan-based initiation rites, promoting church weddings and Christian morality codes in place of traditional marriage regulations (Ndeti, 1972). While some Kamba converted fully to Christianity, others adapted by blending Christian practices with clan traditions, creating a hybrid religious culture (Muthiani, 1973).

Migration, Urbanization, and Clan Identity Today

From the mid-20th century onwards, labor migration to Nairobi, Mombasa, and overseas destinations loosened the clan’s grip on daily life. In urban settings, land rights and ceremonial duties diminished in importance, yet clan identity persisted through naming practices, marriage negotiations, and funeral associations (Muthiani, 1973). Among diaspora communities, clan meetings and contributions for communal causes have kept the mbai relevant, even outside Ukambani.

These transformations reveal a system that, while altered, has proven remarkably resilient—capable of adapting its functions to new political, religious, and economic contexts without losing its core role as a marker of Kamba identity.

Conclusion

The Kamba clan system has for centuries served as the cornerstone of social organization in Ukambani, shaping marriage alliances, land tenure, ritual responsibilities, and networks of mutual aid. Structured as exogamous, patrilineal units, clans (mikai) linked individuals to a common ancestor, a defined territory, and a set of moral obligations that bound the community together (Lambert, 1956; Middleton & Kershaw, 1965).

While colonial administration, Christianity, and large-scale migration have transformed the way clans operate, they have not erased their significance. Land reforms diminished the direct role of the clan in resource control, missionary activity altered ritual functions, and urban migration shifted the clan’s influence from everyday governance to cultural symbolism (Ndeti, 1972; Muthiani, 1973). Yet in both rural and urban contexts, clan affiliation remains a source of identity, social legitimacy, and belonging.

Today, the clan persists not only as an institution of kinship but also as a living link to Kamba history. It embodies the adaptive resilience of the Akamba people—preserving a coherent cultural identity even as the social and political landscapes around them continue to change. In this way, the mbai stands as both a heritage marker and a framework for navigating the challenges of modern Kenyan life.

References

Lambert, H. E. (1956). Land tenure among the Akamba. Nairobi: Government Printer.

Middleton, J., & Kershaw, G. (1965). The Kikuyu and Kamba of Kenya. London: International African Institute.

Ndeti, K. (1972). Elements of Akamba life. Nairobi: East African Publishing House.

Muthiani, J. (1973). Akamba from within: Egalitarianism in social relations. New York: Exposition Press.