Every empire begins by pretending it brings order. The British said they were bringing “civilization” to Kenya; what they brought to Kisii in 1908 was the hut tax, whips, and the rifle. Today, when Kenyans talk about colonial resistance, the story usually jumps straight to the Mau Mau in the 1950s, or maybe the Giriama rebellion under Mekatilili wa Menza in 1914. But before those, in the hills of Gusiiland, the people had already shown that they would not kneel quietly.

The “Kisii Riots of 1908,” as the colonial records call them, were less a riot than a rejection. To the British, it was a disturbance to be punished. To the Abagusii, it was defiance—a refusal to accept foreign dictates over land, cattle, and dignity. The rebellion may not be as famous as Mau Mau, but it was an early sign that the colony would never be pacified without blood.

Colonial Entry into Kisii Country

The Abagusii had settled in the fertile highlands of Nyanza centuries before the British showed up, farming bananas, sorghum, and millet, and tending cattle on ridges that looked down on Lake Victoria’s basin. They were organized in clans rather than a centralized kingdom, which made them hard to conquer. Each ridge was its own republic, bound by kinship, defense, and elders’ councils. To the British, who preferred a single paramount chief to summon with a telegram, this was frustrating.

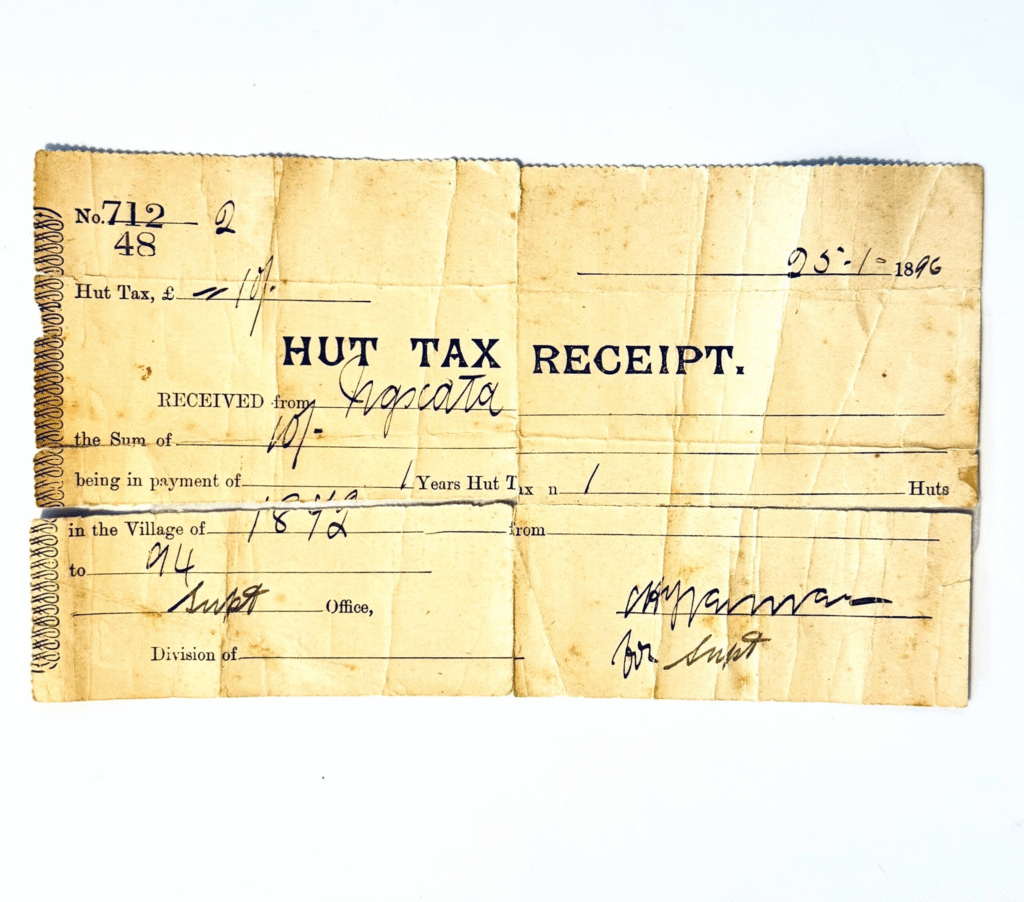

The first British contact with Kisii was not through diplomacy but through patrols. In the early 1900s, colonial officers began pushing into Nyanza to “bring order.” Order meant taxation. By 1908, the hut tax had been imposed, and soldiers began raiding villages for cattle when people refused to pay. To the Gusii, who measured wealth in livestock, cattle raids were acts of war. Adding insult, colonial soldiers humiliated elders, forcing them to bow before strangers who knew nothing of their customs.

The resentment boiled over. That year, Kisii warriors struck back, attacking a colonial station, killing a few officials, and burning property. It was a small spark, but it carried the same message as Waiyaki wa Hinga’s resistance in Kiambu a decade earlier: that conquest was not consent. The British had called it a riot. History knows it as resistance.

The Riot and the Punishment

The violence of 1908 was not spontaneous chaos; it was anger with a target. The Gusii attacked a colonial outpost, killed a few askaris and officials, and made it clear that they would not be bullied into paying hut taxes or surrendering cattle. To the British, this was a “riot,” a word that framed Africans as unruly children acting out. But the actions were deliberate. It was the first time in Nyanza that the empire was openly told it could not rule simply by decree.

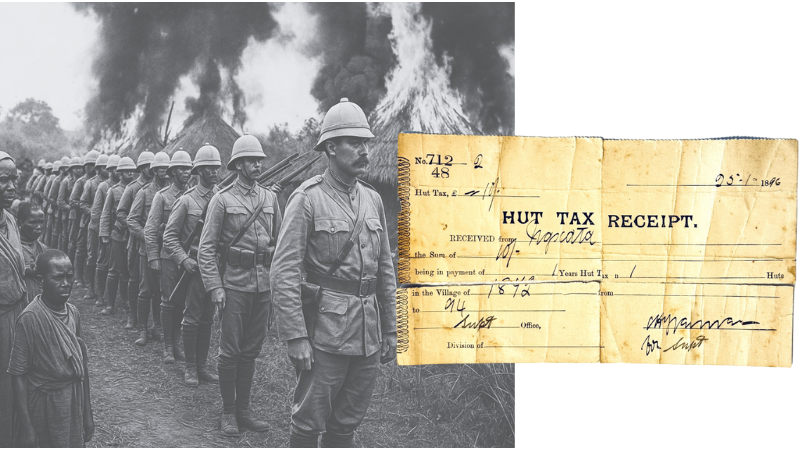

The response came fast and merciless. British officers organized a punitive expedition, a phrase that appears innocuous in colonial reports but in practice meant collective punishment on a massive scale. Soldiers descended on villages, burning huts, seizing herds, and killing indiscriminately. Entire ridges were left smoldering. Cattle—the heart of Gusii wealth and survival—were rounded up and driven away as both fine and weapon. A people who had never known famine in their fertile land suddenly faced hunger.

Eyewitness accounts from Gusii oral history speak of elders executed as warnings, of women and children caught in the violence. Colonial records, careful not to appear too bloodthirsty, speak in euphemisms: “several natives killed resisting arrest,” “property destroyed.” Behind the language was sheer brutality. The point was to make resistance so costly that no one would dare try again.

The numbers vary—some sources speak of hundreds of deaths, others of dozens—but what is clear is that Kisii’s defiance was met with overwhelming force. And yet, the punishment did not achieve what the empire wanted. Fear did not turn into obedience. Instead, it hardened mistrust. The Gusii rebuilt their homes, restocked their herds, and carried the memory of 1908 as proof that the white man’s government ruled by fire and rifle, not by justice.

The British called it a riot and congratulated themselves on restoring order. But order in colonial Kenya was always fragile, always balanced on the barrel of a gun. In Kisii, 1908 was not an ending. It was the first chapter in a long cycle of resistance that the empire would never truly extinguish.

Why Kisii 1908 Matters

The Kisii resistance of 1908 is often dismissed in colonial reports as a footnote, a “minor disturbance” dealt with by firm action. But if we zoom out, it sits squarely in a pattern of early uprisings that showed just how fragile British rule in Kenya really was. Long before Mau Mau, Kenyans were already testing the boundaries of colonial power.

In the 1890s, the Nandi under Koitalel Arap Samoei fought the British railway with spears against rifles, and paid with his assassination. In 1900, Waiyaki wa Hinga had already been buried alive in a colonial prison for daring to resist alien rule in Kiambu. In 1908, it was the Gusii’s turn to face the empire’s punishment. Six years later, in 1914, the Giriama rose under Mekatilili wa Menza at the Coast. Each revolt was local, sparked by taxes, land, or cattle, but together they form a chain of defiance stretching across the country.

The Kisii episode matters because it shows how colonialism was never passively accepted. The Abagusii were not simply waiting for independence to be handed down in 1963; they were already saying no in 1908. The methods of control — hut tax, forced labor, cattle confiscation, punitive expeditions — became the blueprint for later repression across Kenya. Likewise, the determination to resist, even in the face of brutal retaliation, became part of the national memory that fueled later struggles.

It also matters because it complicates the narrative. Too often, Kenyan resistance is told as a Kikuyu story, beginning and ending with Mau Mau. Kisii 1908 reminds us that the whole country was a battlefield of defiance: Nandi, Kisii, Giriama, Luo, Kamba, and many others. Each community has its own scar, its own story of blood shed in the first decades of colonial rule.

The British may have silenced Kisii in 1908 with fire and gunpowder, but they did not erase the lesson. Every act of violence from the state deepened the conviction that colonialism was illegitimate. When independence finally came half a century later, it was built not only on the blood of Mau Mau fighters, but also on the forgotten dead of earlier revolts like Kisii 1908.

Conclusion: A Warning the Empire Ignored

The Kisii Riots of 1908 were not a riot at all. They were a refusal. A statement carved in blood and ash that a people would not be herded like cattle into submission. To the British, it was another “nuisance” to be crushed. To the Gusii, it was a memory that would outlast the empire’s paperwork.

The brutality of the reprisals should have been a warning to the colonizers themselves. Every hut burned, every herd stolen, every elder killed planted the seeds of future rebellions. The empire believed in the myth of permanence, that guns and gallows could turn defiance into obedience. But history kept whispering otherwise: from Koitalel’s Nandi resistance to Mekatilili’s defiance at the Coast, and finally to the forests of Mau Mau, each uprising drew from the same well of anger.

Kisii 1908 matters because it reminds us that resistance did not begin in the 1950s, and it was not the preserve of one community. The swamp of Nairobi, the forests of Nandi, the ridges of Kisii, the sands of Giriama — all were battlegrounds where Kenyans rejected foreign rule long before independence became a slogan.

In the end, the British won every battle but lost the war. The rifles silenced Kisii in 1908, but silence is not consent. It was only a pause before the next uprising, the next refusal. When independence finally came in 1963, it carried with it the ghosts of those forgotten early fighters — people who never lived to see freedom, but who made it inevitable.

Kisii 1908 was not an accident of history. It was the first shout in Nyanza against the empire’s whip. And like every shout across the colony, it echoed into the future, until the day the empire finally crumbled.