1. The Problem with Graves

Kamiti has two kinds of silence. The first belongs to the prison routine—paperwork, footsteps, the steady hum of an institution that has outlived its purpose. The second silence is the one the state built on purpose. Somewhere beneath the dry Nairobi soil, Dedan Kimathi lies in an unmarked grave.

His burial was supposed to erase him. Instead, it became Kenya’s longest unresolved argument with itself.

Kimathi’s ghost still drifts through Kenya’s history, appearing in speeches, murals, and classroom debates. He is invoked when we talk about land, justice, and betrayal. Yet the country that claims to honour him has never found him. It has bronze statues but no grave.

That silence at Kamiti tells us more about Kenya than any monument ever could.

Related reading: Mau Mau Uprising in Kenya (1952–1960) | British Concentration Camps in Kenya

2. How to Erase a Rebel

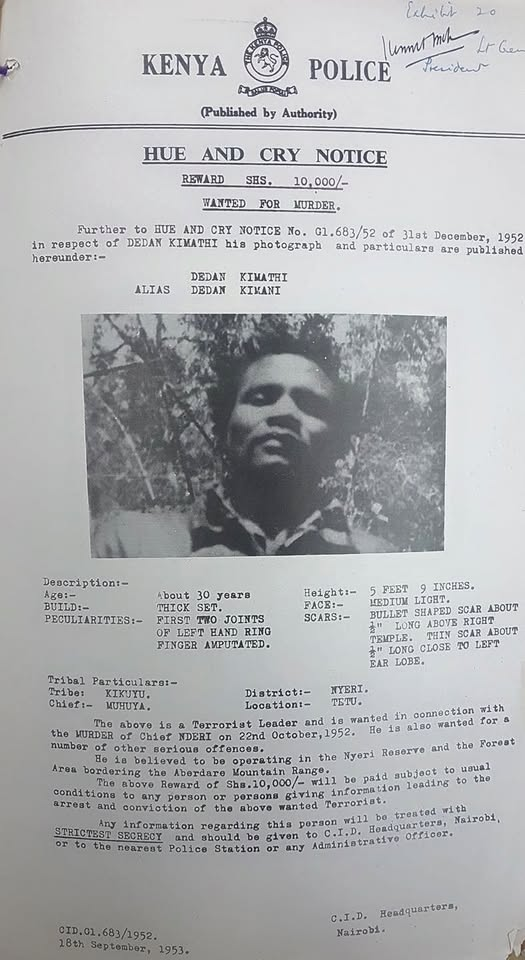

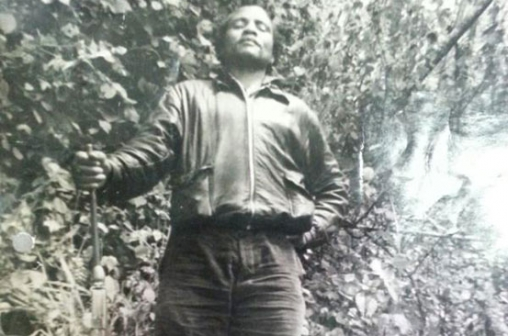

In 1956, the British finally captured the man they called “Kenya’s most wanted.” Dedan Kimathi, wounded and bleeding, was found in the Aberdares Forest wearing a leopard-skin coat. To the colonial authorities, that outfit confirmed every stereotype they had built about Mau Mau—savage, tribal, irrational.

Kimathi’s trial at Nyeri was swift. The court found him guilty of unlawful possession of a firearm and sentenced him to death. On February 18, 1957, he was hanged at Kamiti Prison. His body was buried in secrecy before dawn, in an unmarked spot, without witnesses.

The British had learned from earlier rebellions. Public executions created martyrs; secret graves created silence. The same logic guided how they buried Waiyaki wa Hinga, the first Kikuyu leader to defy them, beneath a road in Kabete in 1892. To rule, you had to bury resistance—literally.

By the time independence came, the colonial government had executed more than a thousand Mau Mau suspects. The Empire was not only fighting a rebellion; it was perfecting the art of erasure.

The real education came not from classrooms but from watching how empire worked. White settlers lived on s3. The Silence After Independence

When Kenya hoisted the flag in 1963, it did not immediately unearth the past. Instead, it buried it deeper.

President Jomo Kenyatta had been imprisoned during the Emergency but kept a cautious distance from the Mau Mau label. The new government wanted order, not revolution. The slogan was “Harambee,” not “It is better to die on our feet.”

Mau Mau veterans found themselves sidelined, their compensation unpaid, their stories untold. Kenya had entered independence without reconciling its own foundation myth. The forests were quiet now, but the memory of what happened inside them was too raw for the new elite to touch.

In Nyeri, Mukami Kimathi—Dedan’s widow—kept asking where her husband was buried. Every government promised to help; every government stalled.

4. The Statue That Stands In for a Grave

In February 2007, President Mwai Kibaki unveiled a bronze statue of Dedan Kimathi at the junction of Kimathi Street and Mama Ngina Street in Nairobi. It was the first time the state had officially honoured him.

The statue shows Kimathi standing tall, a rifle in one hand and a dagger in the other. It faces the direction of the Aberdares, where his rebellion once roared. Around it, office workers pass every day, often without looking up.

That statue is both tribute and substitution. It gave Kimathi a place in public memory but not in the soil. Kenya found it easier to raise a monument than to find his grave.

Kibaki’s government spoke of reconciliation, even as survivors of the British concentration camps were still fighting for recognition. A symbolic victory was easier than a forensic search.

5. A Republic Haunted by Its Own Archives

Finding Kimathi’s remains should be simple: Kamiti Prison still stands. Yet each attempt to locate the grave collapses under bureaucracy, missing files, and the fear of what reopening that chapter might reveal.

In 2003, a joint team of veterans, government officials, and family members visited Kamiti with old maps and witness accounts. Retired warders pointed to possible sites. None were confirmed. Later excavations found nothing but debris.

Colonial archives, now stored in Britain, list hundreds of executions but rarely specify burial locations. As Histories of the Hanged reveals, secrecy was deliberate. The British knew that graves could turn into altars. Kenya inherited those sealed archives—and the fear of opening them.

6. Kimathi Beyond the Myth

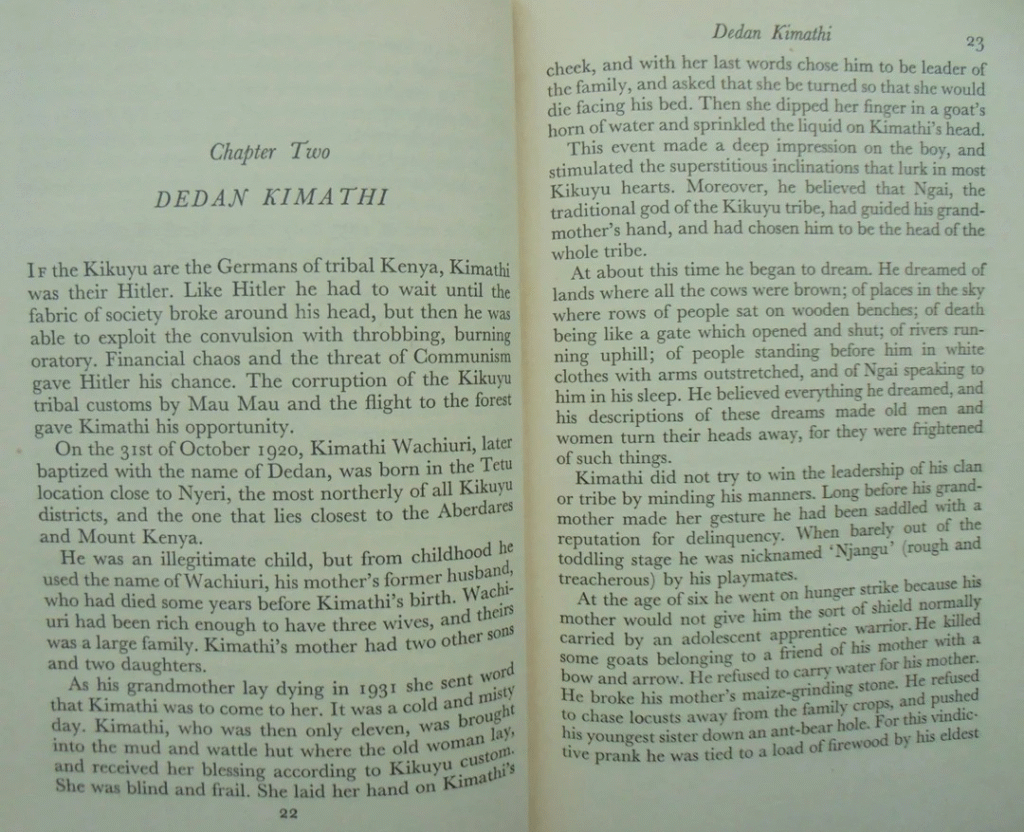

Over time, Dedan Kimathi has been cast in many roles: forest general, nationalist martyr, or bloodthirsty outlaw. But the real story is more complex.

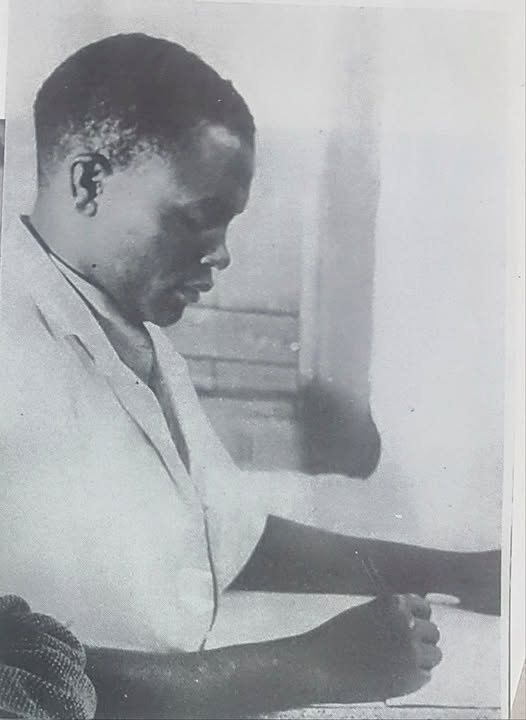

Inside the forest, Kimathi had attempted to build a functioning government. He created a “Kenya Parliament,” issued forest decrees, and even established ranks and regulations. Fighters addressed him as “Prime Minister.” The Kamba in Mau Mau and the Embu and Meru joined his structure, defying the myth that Mau Mau was purely Kikuyu.

The British saw savagery; what Kimathi was attempting was political order. His oaths, often demonized, were constitutional instruments meant to bind loyalty.

Kimathi’s vision was not only about removing the white man—it was about creating a republic from below. The irony is that independent Kenya built its own version of the colonial hierarchy he fought to destroy.

7. The Country That Still Can’t Bury Him

Every decade, a new promise arises to find Kimathi’s remains. Each fades into silence. The last major search was proposed in 2017 after former Chief Justice Willy Mutunga received copies of Kimathi’s trial records. The state’s interest revived briefly, then disappeared again.

There are many reasons for this hesitation. Partly, it’s the difficulty of locating a grave after decades of prison construction. But it is also symbolic. To exhume Kimathi is to reopen Kenya’s uncomfortable history of betrayal, collaboration, and class divide.

As historian Shiraz Durrani notes, Kimathi represented the radical edge of the independence struggle—the side that refused compromise. His ghost still asks what freedom meant for the landless, the poor, and the silenced.

Kenya’s inability to bury him might not be forgetfulness. It might be avoidance.

8. Lessons from Older Flames

Kenya has always argued with its graves. The British buried Waiyaki wa Hinga under a road to prevent pilgrimages. They killed Koitalel arap Samoei under the guise of peace talks and left his body unclaimed for years. Both men were later reburied with ceremony long after their deaths, their spirits folded into Kenya’s national narrative.

Kimathi’s case is different. His grave remains missing because the fight he led never truly ended. The land question, the inequality, and the memory of state violence still linger. His unfinished burial mirrors an unfinished nation.

9. A Republic Is What It Chooses to Remember

A republic’s moral health is measured not by how it celebrates its heroes but by how it remembers its uncomfortable truths. Kenya has found ways to remember Kimathi that do not require confrontation—statues, street names, and school essays. What it has not done is to reconcile with the kind of freedom he imagined.

To find Kimathi’s remains would be a neat ending. To face what he fought for might be far messier. The silence at Kamiti endures not because the files are missing, but because the questions he raised are still unanswered.

In the end, the hanging tree is not just in Kamiti. It runs through Kenya’s history—a reminder that some ghosts are not meant to rest until justice does.

The British campaign against Mau Mau was relentless. By 1954, Operation Anvil had rounded up tens of thousands of Kikuyu into detention camps and barbed-wire villages. The forests were bombed, patrolled, and combed by colonial troops, African Home Guards, and loyalist scouts. Yet Kimathi evaded capture, slipping through the bamboo thickets and rallying fighters even as Mau Mau was being crushed elsewhere.

People Also Ask

How old was Dedan Kimathi when he died?

Dedan Kimathi was 36 years old when he was executed on February 18, 1957 at Kamiti Prison in Nairobi.

Where was Dedan Kimathi buried?

He was buried secretly inside Kamiti Prison in an unmarked grave, as was standard for executed prisoners during the Emergency. The exact burial site remains unknown despite multiple searches by the government and veterans.

For more on this period, explore The Mau Mau Uprising, The British Concentration Camps in Kenya, and Waiyaki wa Hinga: The First Flame of Kikuyu Resistance.

Yet after independence, Kimathi’s memory was inconvenient. Jomo Kenyatta’s government distanced itself from Mau Mau, preferring to build a narrative of national unity rather than rebellion. For decades, Mau Mau veterans lived in poverty, while Kimathi’s name was muted in official histories. He was remembered in whispers, in songs, in stories told around fires in Nyeri, but not in schoolbooks.

It was not until the early 2000s that the state embraced his memory. In 2003, President Mwai Kibaki unveiled a bronze statue of Kimathi in Nairobi city center — leopard skin cloak, dreadlocks, rifle in hand. The man once branded terrorist now stood immortalized in bronze, celebrated as a freedom fighter. It was recognition long delayed, though the questions he embodied — about land, justice, and betrayal — remained unanswered.