Kenyan politics has never really been about ideology. It has been about access. Access to the state, to contracts, to protection, to networks. Political parties, in this context, are not movements built around ideas. They are vehicles built around people. They exist to capture, negotiate, and distribute power.

To understand Kenyan parties, you don’t read manifestos. You follow mergers, defections, and coalitions. You ask who paid for the posters, who got the nominations, who walked away after the election, and who quietly slipped into parastatal boards. That trail tells the real story.

And like everything else in post-independence politics, it begins with KANU.

1. KANU: The Original Machine

The Kenya African National Union was not just a party. It became the operating system of the new state. From the early 1960s, KANU fused with government, parliament, and the provincial administration to form a single political machine.

Early attempts at organised dissent were treated as betrayal. The first major rupture came from within. The faction around Jaramogi Oginga Odinga pushed a more radical, left-leaning critique of how independence gains were being shared. That conflict ended with Jaramogi walking out of government and forming the Kenya People’s Union (KPU).

The state’s response to KPU was not to debate it, but to crush it. The 1969 events in Kisumu and the banning of KPU sent a clear message: opposition was not a legitimate alternative; it was a security problem.

You can see the atmosphere of that moment in the account of the Kisumu massacre and its aftermath.

KANU’s dominance rested on three pillars:

a president with near-absolute power, a loyal bureaucracy, and a network of patronage tied to land and job allocations. Later, this logic would sit at the centre of debates about land, privilege, and exclusion that appear in work on the White Highlands and settler-era economics.

By the time the one-party clause was written into law in 1982, KANU’s real work had already been done. The political culture of obedience was in place.

2. The Early Opposition: Brief Lives, Long Shadows

Formally, Kenya had opposition parties in the 1960s. In practice, they were allowed to exist only as long as they posed no serious challenge to KANU’s hold on power.

KPU’s banning in 1969 showed how far the state would go to protect that hold. Leaders were detained, rallies blocked, and independent voices framed as a threat to national stability. In this environment, parties outside KANU were less organisations and more targets.

The result was a political culture where “opposition” came to mean underground activism, exile, clandestine publications, and church pulpits, not formal parliamentary rivalry. The long arc of defiance by figures like Jaramogi Oginga Odinga belongs in this story.

For almost three decades, KANU existed with no serious party competitor. That would change in the late 1980s and early 1990s.

3. The 1990s: Repeal, FORD, and the Politics of Fragmentation

The opening of political space in the early 1990s was forced, not granted. Economic crisis, donor pressure, church activism, student protests, and a new assertiveness among lawyers and civil society all converged to make one-party rule untenable.

The repeal of Section 2A in 1991 legalised multiparty politics. The first great experiment in this new era was the Forum for Restoration of Democracy (FORD). On paper, it was a broad coalition capable of unseating KANU. In practice, it collapsed under the weight of personal rivalry. FORD split into FORD-Kenya and FORD-Asili ahead of the 1992 election, handing Daniel arap Moi another term.

That pattern would repeat. Opposition leaders agreed that KANU had to go; they rarely agreed on who should replace it.

The wider context and consequences of this transition are mapped in the analysis of Kenya’s shift back to multiparty democracy. The short version is simple: KANU did not win because it was loved. It survived because the opposition refused to stay united.

4. When Opposition Joined Government: The NDP–KANU Moment

By the late 1990s, something strange happened. Instead of fighting KANU from the outside, a major opposition outfit moved inside.

Raila Odinga’s National Development Party (NDP) began cooperating with KANU, first in parliament, then in cabinet, and eventually through a formal merger. Opposition, for a brief moment, became government. KANU rebranded as “New KANU,” and Raila became Secretary General.

Supporters saw this as a tactical move, a way to infiltrate the system. Critics saw it as co-optation. Either way, it confirmed a constant in Kenyan party politics: no vehicle is sacred. Everything can be traded if the incentives are right.

The merger did not last. When Moi tried to impose Uhuru Kenyatta as his successor, the alliance shattered. That fallout would fuel the next major wave of party realignment.

The longer story of these shifts sits inside Raila Odinga’s political journey, which is almost a parallel history of opposition politics itself.

5. NARC 2002: The Coalition That Toppled the Mountain

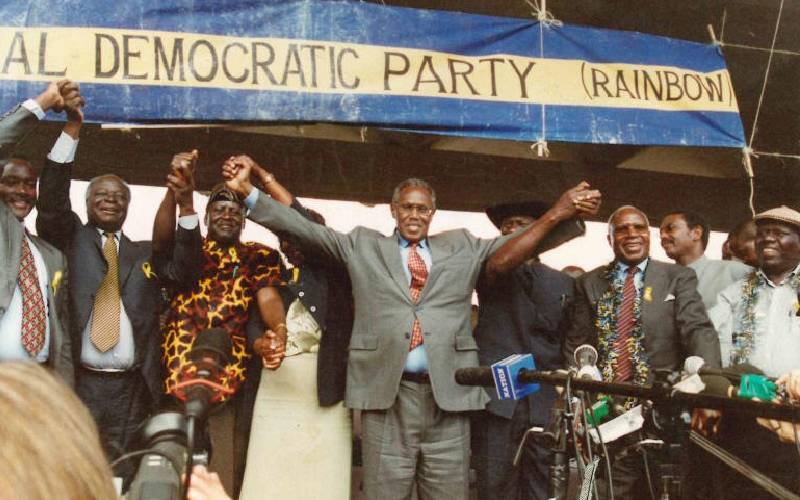

The National Rainbow Coalition (NARC) in 2002 finally did what previous formations had failed to do: remove KANU from power.

NARC brought together Kibaki, Raila, and a range of regional and civic forces under one ticket. It was the closest Kenya has come to a “big tent” political party with broad national appeal. The alliance ended KANU’s four-decade grip on State House.

But again, the problem was not victory. It was what came after.

The famous pre-election MOU between Kibaki’s camp and Raila’s Liberal Democratic Party (LDP) collapsed almost immediately. Positions were reallocated, promises of power-sharing were quietly shelved, and the coalition’s internal contradictions surfaced. The 2005 constitutional referendum split the NARC family into two main camps and eventually produced new vehicles:

- Party of National Unity (PNU)

- Orange Democratic Movement (ODM)

From that point on, Kenyan politics moved decisively into the era of coalitions built for elections rather than governance.

6. The Big Coalition Era: PNU, ODM, and Grand Coalition Government

The disputed 2007 election and the violence that followed forced a power-sharing deal between Kibaki’s PNU and Raila’s ODM. The “Grand Coalition” government that emerged was not a party merger; it was a negotiated ceasefire.

Cabinet seats became tools of balance and appeasement. Parties turned into bargaining chips in a wider struggle over legitimacy, justice, and survival. This is the moment that eventually produced the 2010 Constitution, with its attempt to cage presidential power and entrench devolution.

The broader institutional story of that constitutional re-engineering sits alongside the history of Kenya’s political evolution and the analysis of the Legislative Council’s transformation into a modern parliament.

But at the party level, the lesson was clear: coalitions could keep the peace, but they didn’t resolve the underlying logic of personality-led vehicles.

7. Jubilee, NASA, Azimio, Kenya Kwanza: Parties as Election-Season Companies

From 2013 onwards, coalitions became more sophisticated in branding but not in content.

Jubilee emerged as a merger of several parties around the Uhuru–Ruto ticket, marketed as a clean, modern movement. It was essentially a defensive alliance built under the shadow of the ICC cases. Once those pressures eased and succession politics kicked in, the alliance unravelled.

On the other side, formations like CORD, then NASA, and later Azimio la Umoja repeated the pattern: large, noisy coalitions with impressive launch events and very short institutional half-lives.

Kenya Kwanza, the alliance that carried William Ruto to power, is the latest entry in this tradition. It arrived with a catchy economic story (“bottom-up”) but operates under the same rules: regional kingpins, negotiated party positions, and a constant stream of defections in and out.

To the average Kenyan, it has become obvious that these parties are not long-term homes. They are election-season companies.

This is a big part of why there is so much anger from a younger generation that feels permanently outsourced from the system. That mood is unpacked in the examination of why Kenya’s youth are protesting and what they are protesting against.

8. What This Party History Really Shows

Across all these shifts, a few things are constant:

- Parties are rarely built around ideas. They are built around individuals.

- Mergers and coalitions follow power, not policy.

- Opposition and government can swap sides without any ideological adjustment.

- Fragmentation is a feature, not a bug; it keeps negotiation spaces open.

- After every election, parties weaken while the presidency and state machinery regain centre stage.

Kenya has competition for office, but very little competition of doctrine.

The labels — KANU, FORD, NARC, PNU, ODM, Jubilee, NASA, Azimio, Kenya Kwanza — change more often than the logic underneath them.

To situate this story inside the wider national arc, it belongs alongside the long timeline of Kenya’s political development and the profiles of the presidents and vice presidents who have used these parties as ladders to state power.