Introduction: A Throne in the Grasslands

In the arid lowlands of western Kenya, where trade routes once converged between the Great Lakes and the coast, stood a rare institution in precolonial Kenya: a kingdom. It was not vast, not especially wealthy in gold or ivory, but it held what others did not — a dynasty, a hereditary monarchy, and later, a place in both British reports and nationalist memory.

This was the Wanga Kingdom, and its most famous ruler was Nabongo Mumia.

Nabongo Mumia was not just a king. He was, at different times, a war leader, a host to Arab caravans, an intermediary with the British, and later, a colonial chief whose power was as symbolic as it was compromised. His reign offers a window into the limits and possibilities of African diplomacy in the face of empire.

1. Origins of the Wanga People

The Wanga trace their ancestry to a migrating prince from the Buganda Kingdom named Kaminyi, son of King Mawanda. According to AbaWanga royal tradition, Kaminyi fled Buganda in the 18th century after political upheaval and settled in Tiriki territory (western Kenya), where his son Wanga would rise to found the Wanga Kingdom.

This origin narrative not only ties the Wanga to one of Africa’s most prestigious monarchies but also explains their preference for centralized rule, hereditary succession, and a regal court — all rare features among the Luhya peoples.

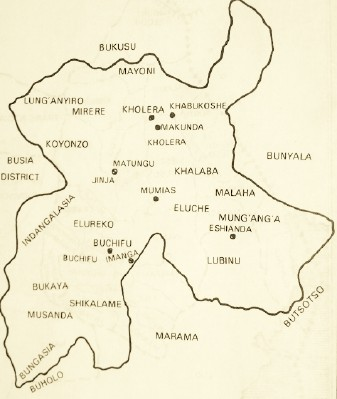

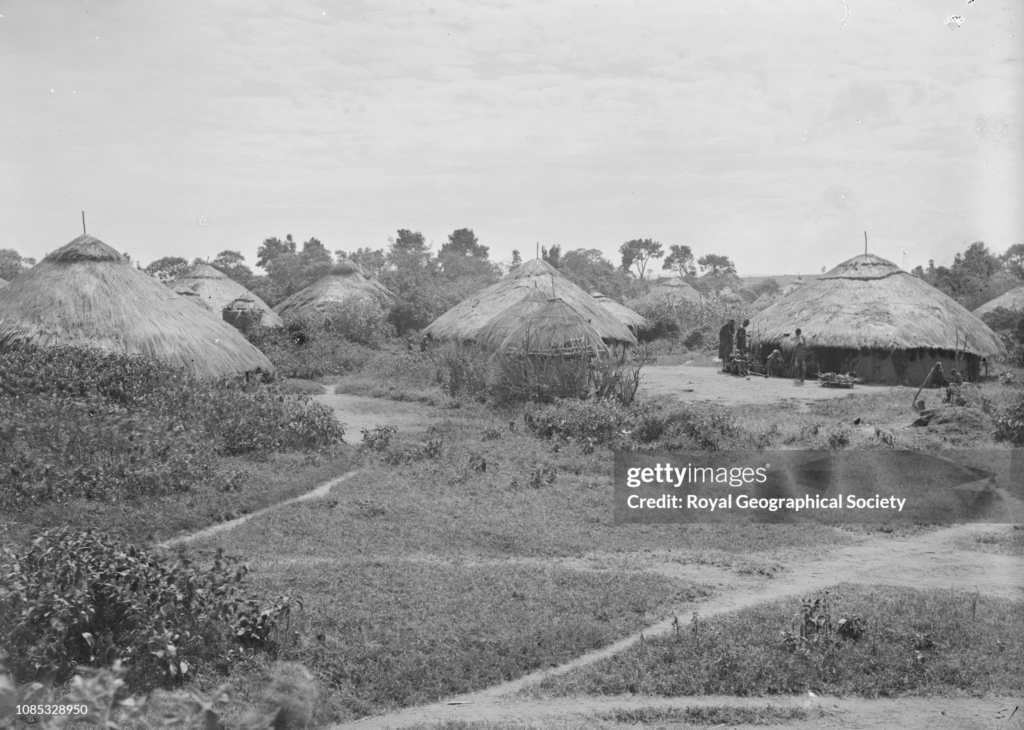

The kingdom’s capital eventually shifted to Elureko, later known as Mumias, which became a center of trade, justice, and ritual. Its rulers adopted the title Nabongo, meaning both king and spiritual head.

By the mid-19th century, the Wanga monarchy had already split once — into Upper Wanga (Mukulu) and Lower Wanga (Elureko) — due to a bitter succession feud between Nabongo Osundwa’s sons. But it was the Elureko branch, led by Nabongo Wamukoya Netia, that retained the sacred regalia and emerged dominant.

II. The Power of the Throne: How the Wanga Were Governed

At its height, the Wanga Kingdom governed through a layered clan-based federal system. The kingdom was divided into 22 co-equal clandoms (Tsihanga) such as the Abashitsetse, Abakolwe, Abashikawa, and others. These were in turn subdivided into tsimbia and tsingongo, forming a nested structure of governance.

Each clan was ruled by a Liguru (chief), advised by a council of elders (Abakali be Lizokho), who were autonomous in local affairs but ultimately subject to the Nabongo, who exercised both ritual and executive control. At court, the king appointed:

- Weyengo – the chief judge

- Eshiabusi – the judicial-executive liaison

- Abakali belitokho – court elders

- Military, diplomatic, and spiritual courtiers

This structure reduced civil war risk and institutionalized succession, though elite rivalries remained common.

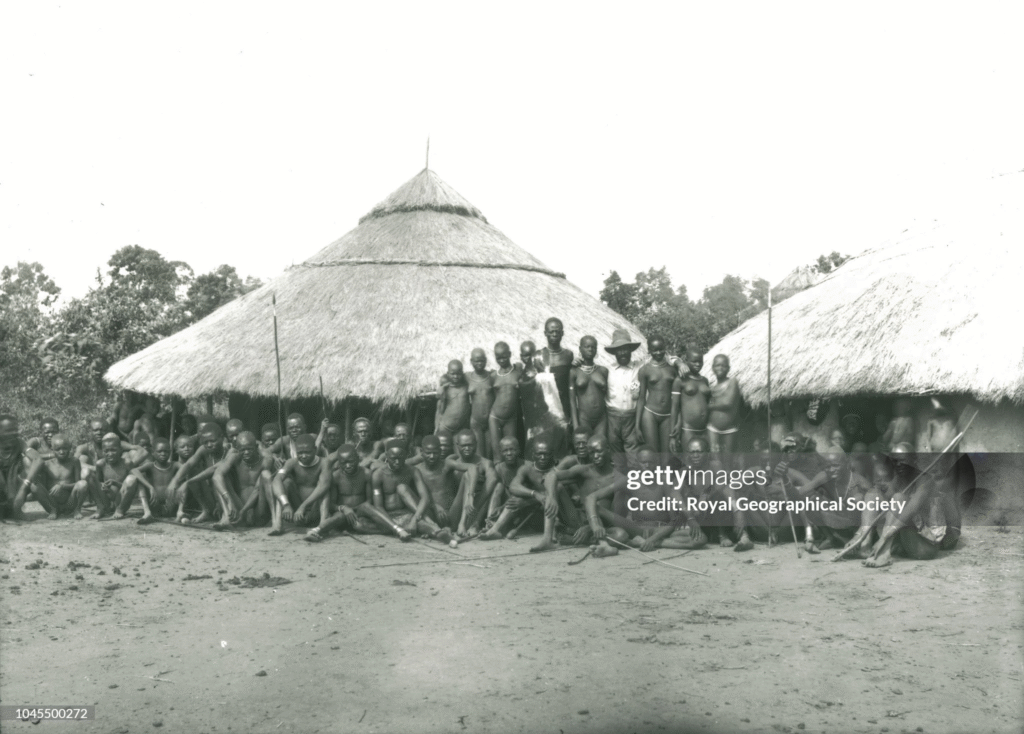

Kavirondo natives at Mumia’s with James Martin and Chief Mumia (plus the wives of Chief Mumia) Jan 11, 1899

The Nabongo also held ritual objects — including sacred spears (likutusi, lishimbishira) and a copper bracelet — signifying his divine authority.

The Wanga economy was rooted in sorghum and millet farming, ironworking, gazelle hunting, and later slave trade mediation. Cultural life revolved around circumcision rituals, polygamy, regimental warfare, and shared clan festivals.

III. Nabongo Mumia: The Strategist on the Throne

Born between 1849–1852, Mumia Shiundu was not the favored heir. His father, Nabongo Shiundu, initially dismissed him as weak and feminine. Through his mother Wamanya’s courtly maneuvering, Mumia was installed over more eligible brothers, a move that caused a dynastic rupture but secured his long rule.

As king, Mumia exhibited extraordinary political intelligence, quickly establishing relations with Swahili-Arab traders such as Sudi bin Hamid and Abdulla bin Hamid. These alliances gave Mumia access to weapons, trade goods, and military support, enabling him to raid rival groups like the Bukusu and Jo-Ugenya.

When British officers arrived in the 1890s, Mumia saw an opportunity. He positioned himself as an intermediary, providing porters, supplies, and “pacification assistance” in exchange for recognition.

By 1908, the British had formally installed Mumia as “Paramount Chief” of the “North Kavirondo” region — an administrative fiction encompassing seventeen culturally unrelated Luhya groups. Mumia’s title, regalia, and legitimacy were used to further indirect rule across western Kenya.

But Mumia never traveled to London for the 1902 coronation of King Edward VII, fearing betrayal. While other kings (e.g. Buganda’s Daudi Chwa) were represented and secured protectorate deals, Mumia’s absence meant the Wanga were folded into the general colonial apparatus, rather than elevated as a distinct native state.

IV. Religion, Education, and Political Miscalculation

Mumia viewed British missionaries with suspicion. He resisted the establishment of mission schools, fearing they would undermine royal authority. In contrast, he allowed Islam to spread, partly as a counterweight to Christian influence, partly due to his admiration for Arab traders.

This decision had consequences.

While the Kikuyu, Luo, and other Luhya groups embraced mission education — producing clerks, teachers, and early political elites — the Wanga fell behind. Today, up to 20% of AbaWanga are Muslim, a legacy of Mumia’s calculated pluralism. But this came at the cost of early political leverage in colonial Kenya.

V. The Fall of a King and the End of a Kingdom

By the 1920s, Mumia’s usefulness to the British had waned. The system of native councils, taxation, and direct district rule reduced the need for a paramount chief. In 1926, his title was quietly retired. He died in 1949, having ruled longer than almost any other African monarch in colonial records.

His successors held only ceremonial influence.

Yet the Wanga monarchy never disappeared. It persisted — quietly — as a custodian of tradition.

VI. The Kingdom Today: Nabongo Peter Mumia II and the Fight for Relevance

In 1974, Mumia’s grandson Peter Shitawa Mumia II was installed as the 14th Nabongo. A modern professional with a career at Toyota East Africa, he only fully embraced kingship upon retirement. He was formally crowned in 2010 at the Nabongo Cultural Centre in Matungu.

Today, Peter Mumia II leads efforts to revitalize the kingdom, not as a sovereign power, but as a cultural, social, and economic institution. The Abawanga WordPress site outlines these ambitions:

- A Constituent Assembly representing all 22 Tsihanga

- Economic investment plans: real estate, agro-industry, banking

- Cultural revival: regalia preservation, circumcision festivals, youth engagement

- Bloc voting strategy for political representation

- International partnerships with other African kingdoms

But challenges abound. The average Wanga citizen identifies more with Kakamega County or the Republic of Kenya than the monarchy. To survive, the Nabongo must offer social utility, not just nostalgic legitimacy.

Conclusion: Between History and Possibility

The Wanga Kingdom is not a relic. It is a palimpsest — rewritten again and again by migration, war, trade, betrayal, and diplomacy. It tells a different story of Kenyan history — one where African kings sat on real thrones, issued real orders, and played real games of power long before colonialism redrew the map.

Mumia’s rule was neither heroic nor cowardly. It was pragmatic. He preserved what he could, negotiated where he had to, and accepted symbolic decline when the balance of forces turned.

The Wanga survived.

And in that survival lies a lesson — that African political sophistication was not always measured by resistance, but sometimes by adaptation.

What to Read Next on KenyanHistory.com

- Who Are the Luhya? A History of the Seventeen Peoples Behind One of Kenya’s Largest Communities

- The Political History of Kenya’s Legislative Council, 1907–1963

- Colonialism in Kenya: Its Origins, Impact and Resistance

- 67 Years a Colony: The True Story of Kenya’s Time Under British Rule

- The History of the Meru People of Kenya