Kenya’s independence on 12 December 1963 marked the end of more than seventy years of British colonial rule. The road to freedom was long, violent, and complex, shaped by both armed resistance and political negotiation. It was not granted as a gift but won through generations of struggle — from the earliest uprisings against imperial occupation to the Mau Mau rebellion and the constitutional talks in London. Understanding how Kenya achieved independence requires tracing how ordinary people, political movements, and freedom fighters challenged a system built on racial inequality and land alienation.

1. Colonial Rule and the Roots of Resistance (1895–1930s)

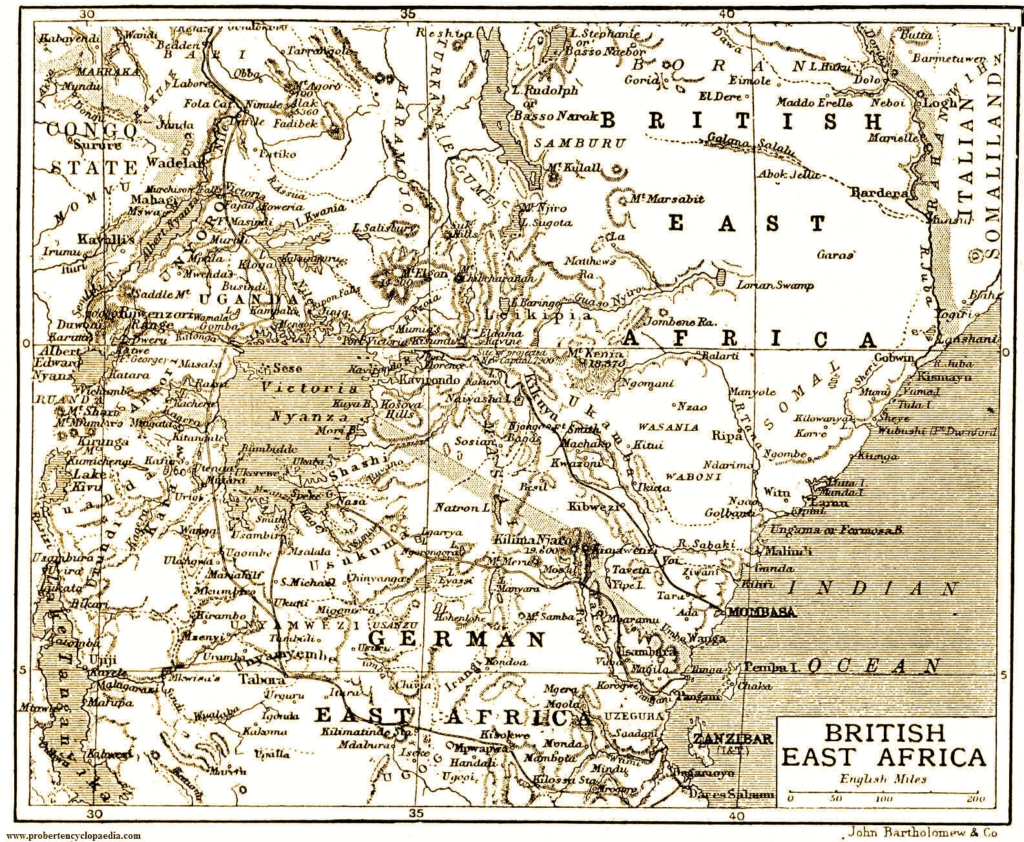

British control over Kenya began formally in 1895 when the region became the British East Africa Protectorate. After the construction of the Uganda Railway (1896–1901), white settlers moved into the fertile central highlands, taking land from African communities. Africans were pushed into reserves and subjected to forced labor through taxes such as the Hut Tax (1901) and Poll Tax (1910).

Maina wa Kinyatti (2008) describes this early period as the beginning of “a colonial economy built on exploitation” (p. 24). Africans provided cheap labor for European farms and construction projects, while colonial authorities restricted African political participation. By the 1920s, Africans could not own land in settler areas, vote, or form independent political associations.

Resistance began almost immediately. The Nandi Resistance (1895–1905) led by Koitalel arap Samoei opposed railway construction and land seizure. Similar uprisings occurred among the Agiriama (1913–1914), Kamba, and Kikuyu. These early revolts were militarily defeated but inspired later political activism.

By the 1920s, African leaders began organizing politically. The Young Kikuyu Association (1919), later renamed the Kikuyu Central Association (KCA), demanded land rights and African representation. Harry Thuku, one of the first nationalists, founded the East African Association (1921), which mobilized workers and farmers against forced labor and low wages. Thuku’s arrest in 1922 sparked protests in Nairobi, marking the first major urban confrontation between Africans and colonial power.

2. Growth of African Nationalism (1930s–1940s)

The 1930s and 1940s saw the rise of educated African elites and labor movements who began to articulate demands for independence. The spread of missionary education produced a new generation of teachers, clerks, and trade unionists who challenged colonial authority through petitions and strikes.

In 1939, World War II changed Kenya’s political landscape. Over 100,000 African soldiers served in the King’s African Rifles, fighting in Asia and the Middle East. On their return, they found that the colonial system had not changed. Land remained alienated, wages were still low, and political rights were denied. This created frustration among the veterans, who became part of the growing nationalist movement (Kinyatti, 2008, p. 63).

The Kenya African Union (KAU), founded in 1944, became the first nationwide African political organization. Led by Jomo Kenyatta, it demanded the return of stolen lands, African representation in government, and the end of racial discrimination. However, the British refused to grant reforms. As Kinyatti (2008) notes, this rejection radicalized many Africans who began to see armed struggle as the only path to freedom.

3. The Mau Mau Uprising (1952–1960)

The Mau Mau rebellion was the defining moment in Kenya’s fight for independence. Rooted in the Kikuyu, Embu, and Meru communities, it was both a liberation movement and a peasant revolt against colonial injustice. The name “Mau Mau” remains debated, but it symbolized a secret oath-bound resistance movement seeking land and freedom (Uhuru na Mashamba).

Causes of the Rebellion

The main grievances were land alienation, labor exploitation, and political exclusion. By 1950, over 7 million acres of fertile land were reserved for fewer than 30,000 white settlers, while Africans were confined to overcrowded reserves. The colonial government ignored petitions for land reform, and police repression intensified (Elkins, 2005).

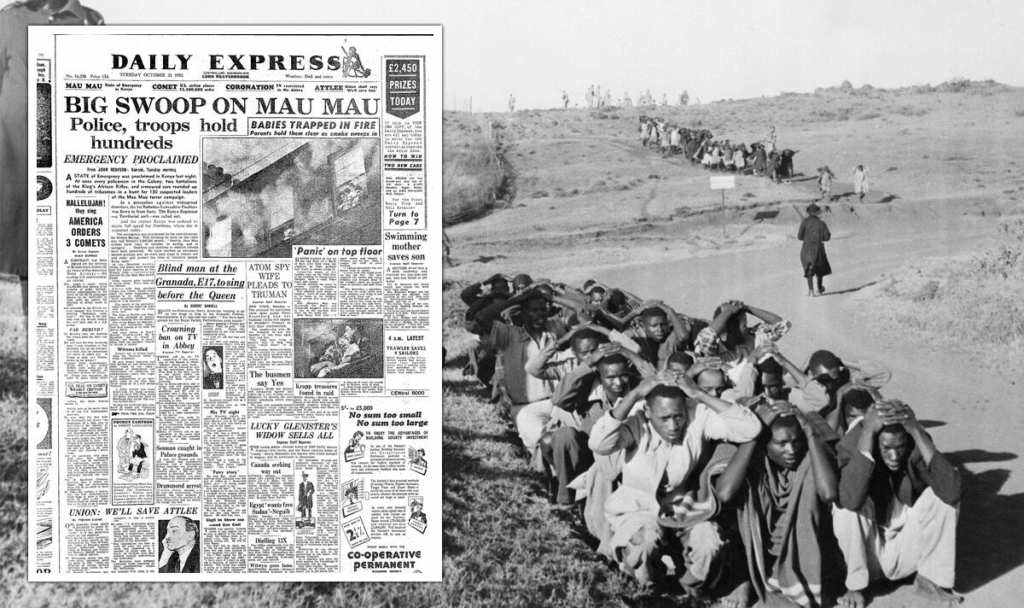

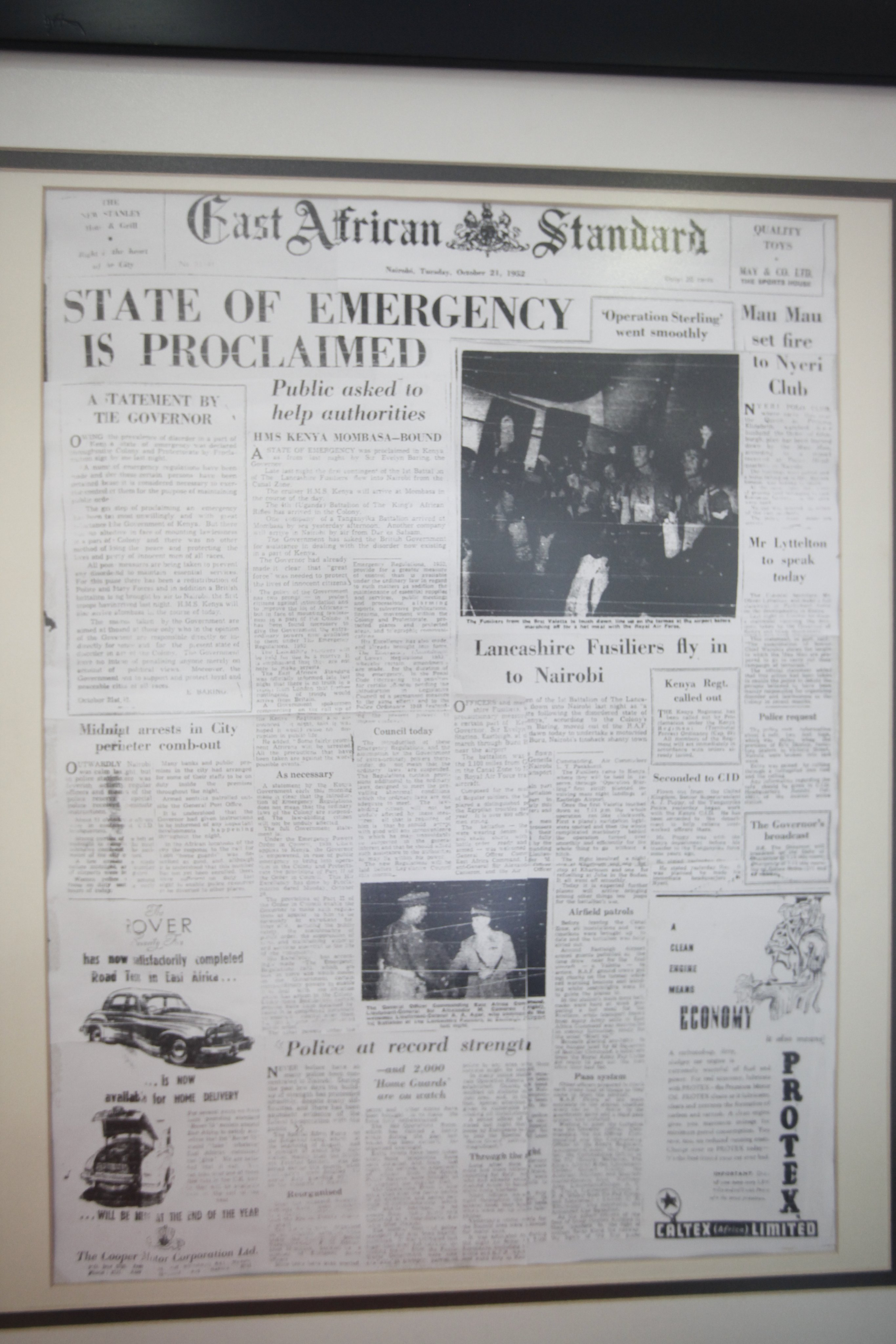

The State of Emergency

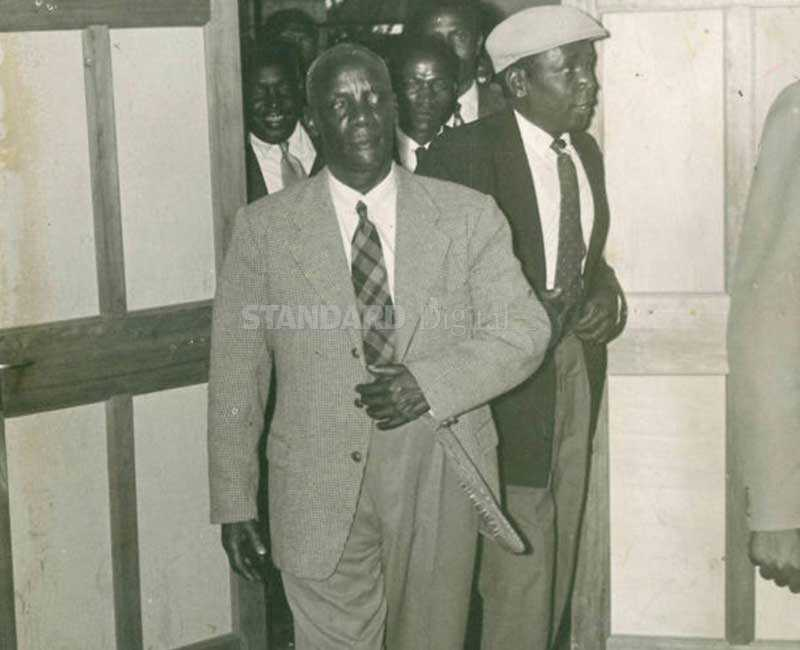

In October 1952, after several attacks on settler farms and the assassination of loyalist chief Waruhiu, the British declared a State of Emergency. The government banned the KAU and arrested nationalist leaders, including Jomo Kenyatta, who was accused of masterminding Mau Mau. Though evidence was weak, Kenyatta was sentenced to seven years in prison during the Kapenguria Trials of 1953 (Anderson, 2005).

The colonial state responded with mass arrests and the creation of a vast system of detention camps and “protected villages.” Over 1.5 million people were confined, and thousands were tortured or killed. In his History of Resistance, Kinyatti (2008) argues that the camps aimed not only to punish but also to destroy the spirit of resistance through forced labor and ideological indoctrination (p. 142).

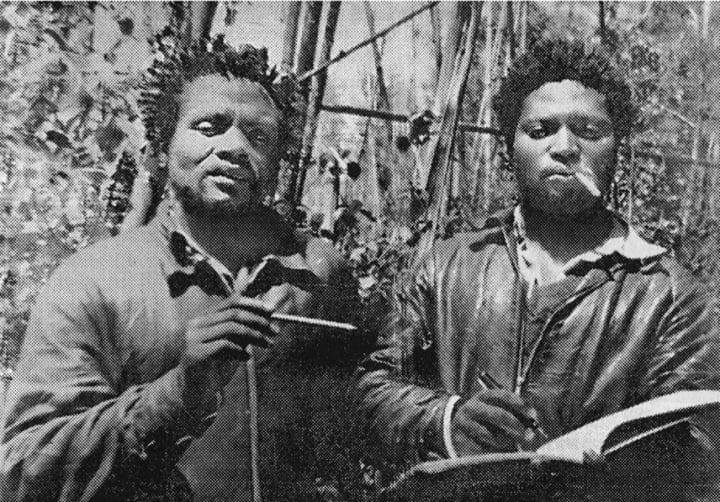

Meanwhile, Mau Mau guerrillas, led by figures such as Dedan Kimathi, Stanley Mathenge, and General China (Waruhiu Itote), fought from the forests of Aberdares and Mount Kenya. Despite limited weapons, they maintained the struggle for years, relying on local support and secret oathing ceremonies to build unity. Kimathi’s writings, preserved in The Dedan Kimathi Papers, show his belief that the war was a moral duty against oppression, not simply tribal revenge (Kinyatti, 1987).

The Hola Massacre and Decline of the Emergency

By the late 1950s, British forces had largely suppressed armed resistance. Dedan Kimathi was captured and executed in 1957, symbolizing both sacrifice and continuity. However, British atrocities — especially the Hola Massacre of 1959, in which eleven detainees were beaten to death — sparked international outrage. The scandal forced Britain to review its colonial policies and accelerated the move toward political reform (Anderson, 2005).

4. Constitutional Negotiations (1958–1963)

While the war raged, African politicians in detention and exile continued to push for independence through constitutional means. Britain realized that it could not sustain colonial rule indefinitely, especially after similar independence movements in Ghana (1957) and Tanganyika (1961).

The Lennox-Boyd Constitution (1958) expanded African representation in the Legislative Council (LEGCO), and in 1960, the first Lancaster House Conference was convened in London. This brought together nationalist leaders such as Tom Mboya, Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, James Gichuru, and Mbiyu Koinange to negotiate Kenya’s political future.

Two main parties emerged:

- The Kenya African National Union (KANU), led by Kenyatta’s allies, favored a strong centralized government.

- The Kenya African Democratic Union (KADU), led by Ronald Ngala and Daniel arap Moi, advocated for regional autonomy (majimboism) to protect smaller communities.

After further negotiations in 1962, Kenya was granted internal self-rule on 1 June 1963, with Jomo Kenyatta as Prime Minister. The final Lancaster House Agreement (1963) set the date for full independence on 12 December 1963.

5. The Meaning of Independence

At midnight on 12 December 1963, the Union Jack was lowered, and the Kenyan flag rose over Nairobi’s Uhuru Park. The new state adopted the motto Harambee — “pulling together” — as its vision for national unity.

Independence brought political sovereignty, but many colonial structures remained. Land ownership inequalities persisted, and the economy continued to depend on export agriculture. As Kinyatti (2008) observes, “freedom was achieved politically, but not economically” (p. 298). Nonetheless, independence was a profound victory for Africans who had endured decades of subjugation.

6. Legacy of the Struggle

Kenya’s independence was the result of a century-long continuum of resistance. From the Nandi and Giriama wars to the Mau Mau rebellion and political negotiation, each generation contributed to the eventual dismantling of empire.

Dedan Kimathi’s execution symbolized sacrifice; Kenyatta’s release and leadership symbolized reconciliation. Both paths — the armed and the diplomatic — converged in 1963. As later independence leader Tom Mboya said, “We fought in different ways, but for one purpose — Uhuru.”

Kenya’s story shows that decolonization was neither sudden nor peaceful. It was achieved through endurance, unity, and the refusal of an entire people to accept subordination.

References

Anderson, D. (2005). Histories of the hanged: Britain’s dirty war in Kenya and the end of empire. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Elkins, C. (2005). Imperial reckoning: The untold story of Britain’s gulag in Kenya. New York: Henry Holt.

Kinyatti, M. W. (1987). Kenya’s freedom struggle: The Dedan Kimathi papers. Nairobi: Zed Press.

Kinyatti, M. W. (2008). History of resistance in Kenya, 1884–2002. Nairobi: Mau Mau Research Centre.