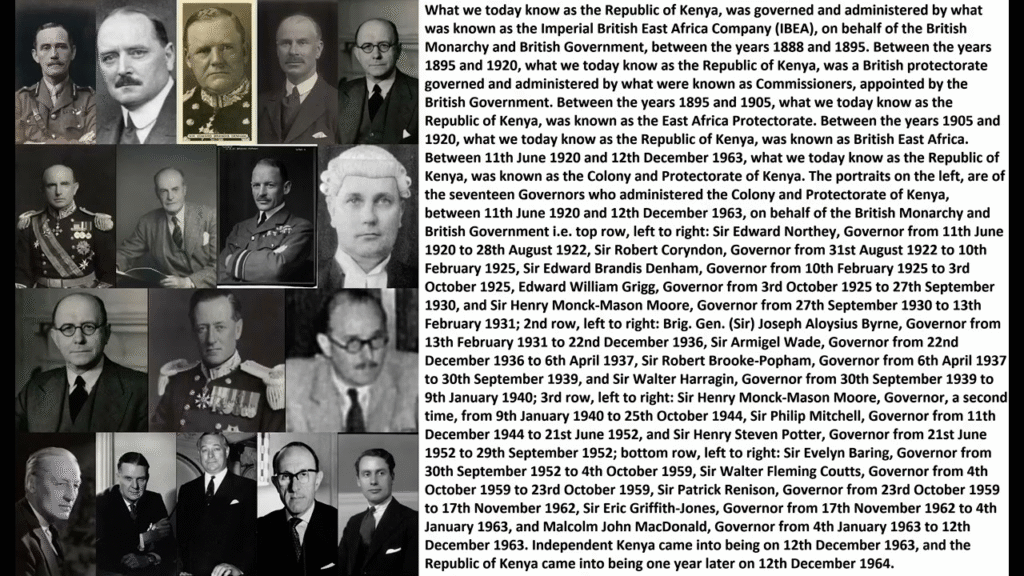

In July 1920, the British government formally transformed the East Africa Protectorate into the Colony and Protectorate of Kenya. This change marked the start of a new phase of colonial rule in which the governor represented the Crown, and settlers consolidated their political and economic influence. Between 1920 and independence in December 1963, Kenya’s administrative system evolved through phases of settler dominance, wartime mobilization, limited African representation, and authoritarian emergency rule. The colonial administration was headed by governors who each left their imprint on the colony, shaping structures that would later influence independent Kenya (Anderson, 2005).

The Colonial State Structure

The colonial administration in Kenya after 1920 was deliberately designed to be centralized, hierarchical, and exclusionary. Its overriding goal was to maintain British control, safeguard settler privilege, and ensure a steady supply of African labor for the economy. The structure rested on a chain of authority that concentrated power in the governor’s office while filtering control down to chiefs at the village level.

Executive:

At the top stood the governor, appointed directly by the British Crown. He wielded supreme authority as both head of state and head of government in the colony. The governor was not only commander-in-chief of the armed forces but also the chief legislator and final arbiter of justice through his power to assent to or veto laws. The governor presided over the Executive Council (EXCO), which was initially composed of senior colonial civil servants such as the Attorney General, Treasurer, and heads of major departments. From the 1920s, European settlers were co-opted into this council, formalizing their influence on executive decision-making. While settlers had no formal constitutional authority beyond their seats, successive governors relied heavily on their support to govern, particularly because Britain lacked the financial resources to administer the colony without settler cooperation (Clayton & Savage, 1974).

Legislature:

The Legislative Council (LEGCO) became the principal law-making body. Established in 1907, it initially had only European members, but by 1920, it was expanded to include both nominated and elected settler representatives. The council passed ordinances that structured taxation, land allocation, labor recruitment, and policing. Asian representation was reluctantly conceded in 1924 after sustained protests, but even then it was restricted and unequal compared to the number of settler seats. Africans were systematically excluded until 1944, when Eliud Mathu was nominated as the first African member. By then, the LEGCO had become a forum for contestation over racial privilege: settlers resisted any dilution of their dominance, Asians pressed for equality, and Africans demanded greater representation. Still, the structure remained weighted heavily in favor of Europeans throughout most of the colonial period (Maxon, 1993).

Judiciary:

The colonial legal system was anchored in English common law, but in practice it reinforced racial hierarchies. Europeans accused of crimes were tried in superior courts, often receiving lenient treatment, while Africans were subjected to a dual system. Ordinary disputes were handled in “Native Tribunals” applying codified versions of customary law under supervision of district commissioners. More serious cases fell under colonial magistrates’ courts, which applied punitive ordinances specifically designed to regulate African lives, such as pass laws, labor ordinances, and restrictions on movement. The judiciary thus functioned less as a neutral system of justice than as an instrument of control, ensuring African compliance with labor demands and settler economic interests (Anderson, 2005).

Provincial and District Administration:

The backbone of day-to-day colonial control was the provincial and district administration, often referred to as the “DC system.” The colony was divided into provinces headed by provincial commissioners, which were further subdivided into districts overseen by district commissioners. These administrators wielded immense discretionary power: they could issue passes, approve land transfers, impose collective punishments, and supervise taxation. They also acted as magistrates, combining judicial and executive powers in ways that blurred lines of accountability. Below them, divisions and locations were controlled by African chiefs and headmen appointed under the Native Authority Ordinance (1912, reinforced in the 1920s). Chiefs were tasked with collecting hut and poll taxes, recruiting forced or “communal” labor, and enforcing colonial ordinances. In many cases, they were unpopular at the local level, seen as collaborators or “chiefs of the government” rather than leaders of their communities. Still, the chief system allowed the colonial state to extend its authority deep into rural areas at minimal cost to the British Treasury.

Settler Influence:

By the 1920s, Kenya had become a settler colony in all but name. White settlers wielded disproportionate power through their elected positions in the LEGCO and their influence in the Executive Council. They were the driving force behind land alienation policies that entrenched the “White Highlands” as exclusive European zones, displacing Africans into crowded reserves. Settlers also pressed for laws that secured African labor for their farms, such as punitive taxation, pass systems, and anti-squatter legislation. Their dominance in the political sphere was matched by economic privilege: they controlled the most fertile lands, received government subsidies, and had preferential access to credit and markets. Africans, by contrast, were legally restricted in cash crop production until the 1950s. Thus, while the colonial state formally answered to London, in practice it functioned as a partnership between British administrators and European settlers, with Africans excluded from meaningful power until the late colonial reforms (Clayton & Savage, 1974; Berman, 1990).

Evolution of the Administration

1920s–1930s: Settler Consolidation

The early decades of the colony were marked by the entrenchment of European settler dominance. Africans were denied political rights and instead governed through chiefs and indirect rule. Economic policy was designed to force Africans into wage labor: the hut and poll taxes compelled households to earn cash, which in practice meant working on settler farms or in colonial projects (Berman, 1990). Governors such as Sir Edward Grigg openly championed settler interests, presenting European farmers as the “civilizing vanguard.” The Carter Land Commission (1932–1934) codified land segregation by dividing territory into European, Native, and Crown lands, formalizing the dispossession of African communities. This period also saw restrictions on African cash crop production, reserving lucrative crops like coffee for Europeans while confining Africans to subsistence farming in overcrowded reserves. Politically, Africans were excluded from the Legislative Council, while settlers consolidated their influence, lobbying for increased representation and autonomy. By the end of the 1930s, Kenya’s administrative system was firmly skewed toward protecting settler privilege at the expense of African rights.

1940s: War and Representation

World War II brought Kenya into the global conflict as a strategic base for the Allies in East Africa. Nairobi hosted military headquarters, and tens of thousands of Kenyan men were conscripted or recruited into the King’s African Rifles and Carrier Corps, serving in Ethiopia, Burma, and elsewhere. The war expanded the colonial bureaucracy to manage wartime logistics, taxation, and labor mobilization. It also exposed Africans to new political ideas as returning soldiers demanded recognition for their sacrifices (Parsons, 1999). In 1944, the British, under pressure, appointed Eliud Mathu as the first African member of the Legislative Council. While this was a token gesture, it marked a historic break in the color bar of representation. At the same time, African political activism intensified through organizations such as the Kenya African Union (KAU), founded in 1944. Thus, the 1940s were a turning point: the administration remained hierarchical and settler-dominated, but African voices began to find entry points into official politics (Maxon, 1993).

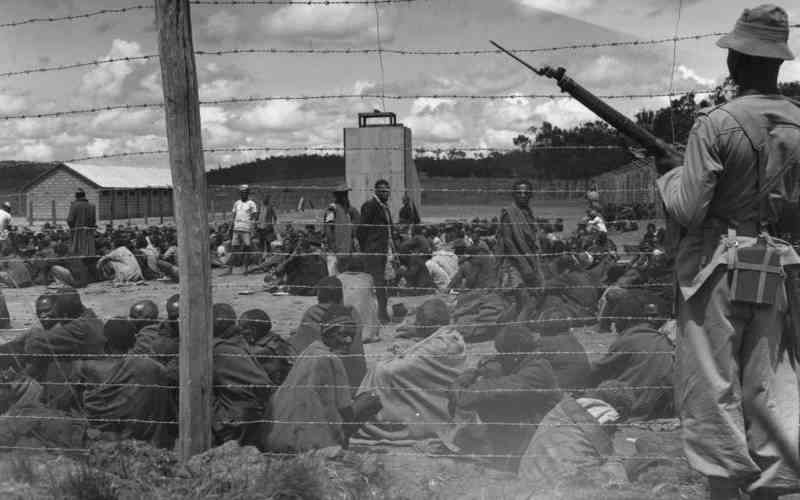

1950s: The Emergency and Reforms

The 1950s were dominated by the Mau Mau uprising (1952–1960), which forced the colonial administration into its most repressive phase. Governor Sir Evelyn Baring declared a State of Emergency in October 1952 after the assassination of Chief Waruhiu. Emergency regulations gave extraordinary powers to the administration: detention without trial, mass arrests, and forced resettlement of entire communities. Over one million Kikuyu, Embu, and Meru were confined in fortified villages, while an extensive system of detention camps housed thousands of suspected Mau Mau sympathizers (Elkins, 2005). The provincial and district administration became militarized, and chiefs were pressured to collaborate in suppressing the revolt. At the same time, Britain recognized that repression alone could not secure Kenya’s future. The Lyttelton Constitution (1954) introduced a Council of Ministers with limited African participation, breaking settler monopoly in government. By 1957, the first African elections to LEGCO were held, sending representatives such as Tom Mboya and Oginga Odinga into formal politics. These reforms signaled that the colonial administration was preparing, however reluctantly, for African majority rule.

1960–1963: Transition to Independence

The early 1960s marked the final phase of colonial administration as Britain accepted that Kenya could no longer be held as a settler colony. Under Governor Sir Patrick Renison, the first Lancaster House Conference (1960) brought together African leaders and settlers in London to negotiate a constitutional framework. The talks produced a multi-racial system, but settlers’ insistence on regional autonomy (majimboism) clashed with nationalist demands for a strong central state. In 1961, political detainee Jomo Kenyatta was released, and his party, the Kenya African National Union (KANU), won elections later that year. Sir Malcolm MacDonald, the last governor, oversaw the delicate transition: forming coalition governments, negotiating land transfer schemes, and preparing the machinery of self-rule. The Lancaster House Conferences of 1962 and 1963 finalized the independence constitution. On 1 June 1963, Kenya achieved internal self-government with Kenyatta as prime minister, and on 12 December 1963, the Union Jack was lowered for the last time as Kenya became a fully sovereign nation.

Governors of Kenya, 1920–1963

| Name | Years | Role | Key Events/Policies |

|---|---|---|---|

| Major Gen. Sir Edward Northey | 1920–1922 | Governor | Oversaw the formal transition from Protectorate to Colony status; expanded settler land rights and strengthened the hut and poll tax systems to secure African labor. |

| Sir Robert Coryndon | 1922–1925 | Governor | Balanced settler ambitions with imperial caution; clashed with Indian leaders over equal rights, reinforcing racial divisions in politics. |

| Sir Edward Grigg | 1925–1930 | Governor | Strong pro-settler stance; advanced White Highlands settlement; initiated the Carter Land Commission (1932) that formalized land segregation. |

| Sir Joseph Byrne | 1930–1935 | Governor | Managed Kenya through the Great Depression; promoted settler agricultural subsidies while tightening African labor control. |

| Henry Moore (Acting) | 1931 | Acting Governor | Brief caretaker during Byrne’s absence; maintained ongoing policies without major reforms. |

| Sir Robert Brooke-Popham | 1937–1939 | Governor | Oversaw growing settler-African tensions on land; faced mounting labor disputes and early signs of African political mobilization. |

| Sir Henry Monck-Mason Moore | 1939–1944 | Governor | Directed Kenya’s role as a WWII base; recruited tens of thousands of Africans into the Carrier Corps and military service, deepening African exposure to global politics. |

| Sir Philip Mitchell | 1944–1952 | Governor | Marked a turning point with the appointment of Eliud Mathu as the first African LEGCO member in 1944; saw rapid growth of African political organizations and trade unions. |

| Sir Evelyn Baring | 1952–1959 | Governor | Declared the State of Emergency during the Mau Mau uprising; implemented villagization and detention camps; his repressive policies remain highly controversial. |

| Sir Patrick Renison | 1959–1962 | Governor | Managed Kenya during the decolonization push; saw the emergence of KANU under Kenyatta and KADU under Ngala; tried to balance settler resistance with nationalist demands. |

| Sir Malcolm MacDonald | 1963 | Governor | Oversaw the final transfer of power; guided the Lancaster House settlement into practice; handed authority to Jomo Kenyatta on 12 December 1963. |

Legacy

The colonial administration left Kenya with a centralized and hierarchical state system designed for control rather than inclusive governance. It entrenched ethnic divisions through land allocation policies, empowered chiefs as intermediaries, and privileged settler interests. At independence, Kenya inherited not only an elaborate provincial administration but also deep social inequalities and authoritarian habits. These legacies shaped the challenges of post-independence governance, including debates about land, ethnicity, and the concentration of presidential power.

References

Anderson, D. (2005). Histories of the Hanged: Britain’s Dirty War in Kenya and the End of Empire. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Berman, B. (1990). Control and Crisis in Colonial Kenya: The Dialectic of Domination. London: James Currey.

Clayton, A., & Savage, D. (1974). Government and Labour in Kenya 1895–1963. London: Frank Cass.

Elkins, C. (2005). Imperial Reckoning: The Untold Story of Britain’s Gulag in Kenya. New York: Henry Holt.

Maxon, R. M. (1993). An Introduction to the History of East Africa. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers.