In the grand plan of British colonialism, no policy reveals the racial logic of empire more starkly than the alienation of African land in Kenya. At the heart of this project was the so-called “White Highlands”—a lush, fertile expanse that became both the symbol and substance of settler dominance. But this was more than land theft. It was the blueprint for a racialized economy that would shape Kenya’s political and economic history long after the Union Jack came down.

The Invention of the Highlands

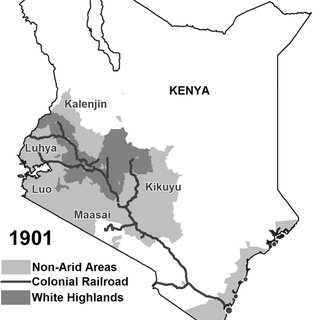

The term “White Highlands” was a legal fiction—and a deadly serious one. Though the land was traditionally held by various African communities, especially the Kikuyu, the British colonial state designated nearly 20% of Kenya’s arable land as reserved for Europeans. This began with the 1902 Crown Lands Ordinance, which declared all “waste and unoccupied” land as property of the Crown—effectively dispossessing entire communities overnight.

The Highlands were not just the best land in terms of rainfall and soil; they were strategically located near railway lines and administrative centers. In the imperial imagination, Kenya was to become a white settler colony, like Rhodesia or South Africa. And so settlers flooded in—encouraged by the state, given land grants, and supported by an infrastructure designed to privilege European farming.

Race, Law, and Labour

By the 1920s, Kenya was a fully racialized economy. The Highlands were for whites. The reserves were for Africans. Indians could trade, but could not own land in the European zone. The spatial segregation reinforced economic exclusion: settlers had access to credit, technical advice, and export markets. African farmers were forbidden from growing certain cash crops, most infamously coffee, until the late colonial period.

And then there was labor.

The White Highlands created a demand for African labor, but only in a strictly exploitative form. The state imposed hut and poll taxes to force Africans into the wage economy. Pass laws controlled their movement. Vagrancy laws criminalized the idle. The labor supply was thus not merely encouraged—it was coerced. By the 1940s, many Africans were working on land that their own families had been evicted from a generation earlier.

Resistance: From Squatting to Mau Mau

The injustice of the Highlands was not lost on those it displaced. Some resisted by squatting—remaining on European farms as tenants or informal workers. Others joined peasant movements and formed associations like the Kikuyu Central Association, which pushed for land rights in the 1920s and 30s.

But it was the Mau Mau uprising of the 1950s that finally exposed the fragility of settler dominance. Though often reduced to a tribal rebellion, the Mau Mau was in large part a land war—a desperate attempt by the Kikuyu to reclaim ancestral territory. The British responded with brute force: concentration camps, collective punishments, and mass executions. The Highlands, once a symbol of imperial pride, had become the site of its bloodiest contradiction.

Decolonization and the Land Question

When independence finally came in 1963, Kenya faced a paradox. The land that had caused so much pain remained in settler hands. The political class, now led by Jomo Kenyatta, had two immediate challenges: preventing the collapse of agricultural production, and avoiding a race war.

The solution was a compromise: the Million Acre Scheme. Backed by loans from the British government and the World Bank, the program aimed to buy land from willing settlers and resettle African smallholders. The goals were threefold—redistribute land, maintain agricultural output, and preserve peace.

The Million Acre Scheme: An Uneven Experiment

Launched in 1962 and formalized after independence, the scheme was ambitious but flawed. Large estates were subdivided and sold to African farmers, often at subsidized rates. Settlement schemes like Mwea, Olenguruone, and Molo emerged across the former Highlands.

But the program had baked-in contradictions. Access was tilted toward the politically connected. Many of the beneficiaries were not the landless poor but middle-class Africans, former chiefs, and educated elites. The purchase model also meant that landlessness persisted—this was not redistribution by justice but by market transaction.

Moreover, the debt burden of the scheme limited its long-term success. Many smallholders struggled to repay loans. Without significant technical support, productivity remained low. By the late 1970s, the scheme had slowed, and land inequality had re-emerged in new, Africanized forms.

The Legacy of the White Highlands

Today, the ghost of the White Highlands still haunts Kenya. The country’s most fertile lands remain disproportionately controlled by a small elite—now African, but structurally inherited from the colonial order. Land remains a flashpoint of political tension, visible in election cycles, ethnic clashes, and rural poverty.

Ironically, the very laws that created the Highlands—the Crown Lands Ordinances and their successors—still influence land tenure systems. Reforms have been attempted, including the 2010 Constitution’s land chapter, but implementation remains weak.

The myth of postcolonial land justice was never fully realized.

Conclusion: A Settler Project Without Settlers?

The history of the White Highlands is not just a story of colonial brutality. It is a mirror of Kenya’s incomplete transition. Independence ended the political dominance of the settlers, but not the economic structures they built. The Highlands remain—less white, but still exclusive.

And that is the real tragedy. Kenya inherited a settler economy without settlers. The land changed hands, but the system endured.